There's no better way to spark new ideas than going – or getting pushed – out of your comfort zone. As part of our Time/Place program, we sent Sébastien Robert to Cambodia in search of a dying form of traditional music.

For WeTransfer's Time/Place initiative, we sent six students on surprise trips in the summer of 2018. From Costa Rica to Cambodia, they immersed themselves in new cultures to feed a different kind of creative energy. Meet the six students here.

Sébastien is a French sound artist, photographer and master’s student at the ArtScience Interfaculty in the Netherlands. His ongoing research project You’re no Bird of Paradise focuses on traditional music and rituals that are in danger of disappearing. We sent Sébastien in search of a Cambodian music in danger of dying out.

"Phleng Arak - also called Phleng Memot - is a Khmer traditional music performed during magical ceremonies to call spirits when there is no rain, if animals or humans are struck by disease, or when an important event is planned," he explains.

"Almost extinguished after the Khmer Rouge period – when music from past was forbidden and most of the musicians killed – Phleng Arak is now facing new risks. There are fewer opportunities to perform it and fewer musicians able to play it.

"Instead of thinking too much about it, I assumed that a lot of my ideas and beliefs were totally wrong. To be honest, I felt like a total beginner, which was both exciting and scary."

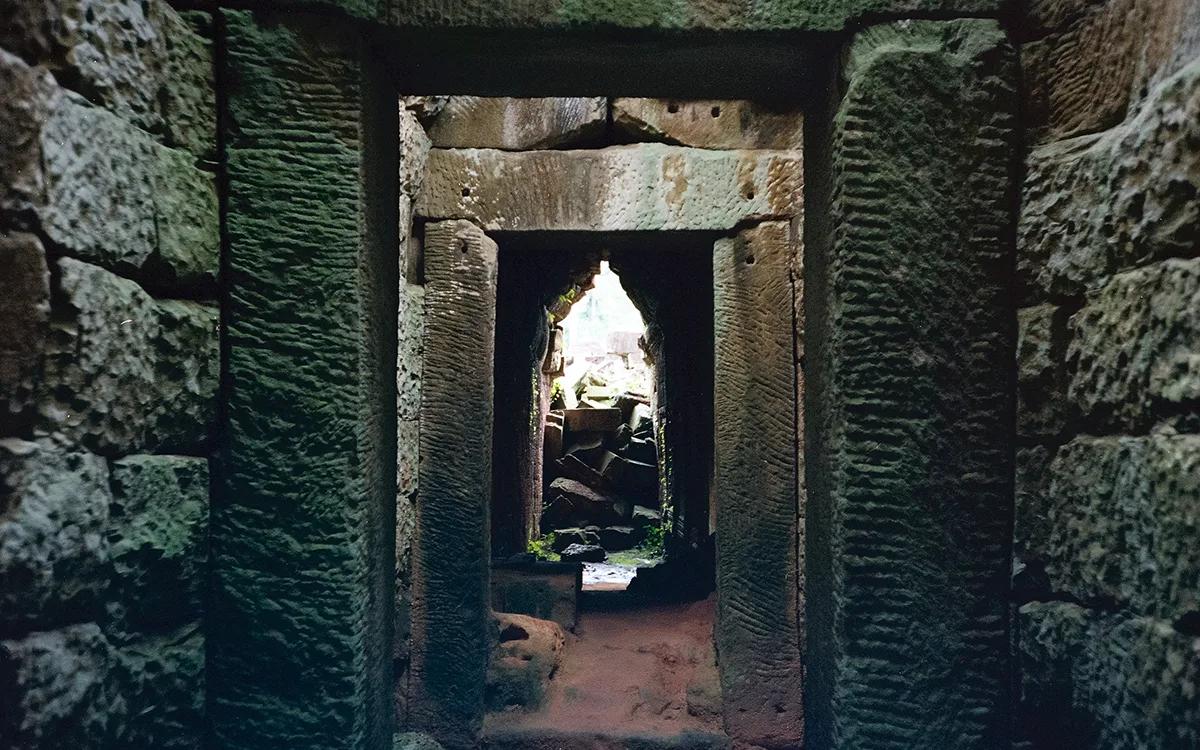

Below you can read his day-by-day diary, alongside photos he took throughout his trip.

Day 1 – Arrival

I arrived in Phnom-Penh after a long journey from Amsterdam via Guangzhou in China.

I always found the first minutes in a new country so magical; the change of scenery and the unknown smells and sounds give you a feeling of being reborn for a moment. It is such an intense, almost overwhelming sensation.

I quickly checked in at my hotel and got ready to explore the city. My trick is to always go from east to west in order to get as much sunlight as possible behind me for taking photos. Then I try to reach some roof or restaurant with a view to get different perspectives on the cityscape.

At the end of the afternoon, I headed to the Bophana Audiovisual Center – a cultural institution and archive founded by film director Rithy Panh. I was able to listen to plenty of records and podcasts from the past but also watch video archives. Fruitful dig; I found quite some amazing records there.

Day 2 – Kampong Chhnang

I left Phnom-Penh early in the morning for my next destination: Kampong Chhnang. As soon as I got off the bus I met a friendly driver called Kosal.

Since we had the whole day in front of us, we first stopped by the harbour where I immersed myself in the fantastic mess taking place before my eyes. Intense verbal fighting between fish buyers discussing the price of the catch of the day, kids playing with little wooden rafts, farmers trying to transfer the cows from a boat to their truck without wounding anyone and the extremely loud sounds of the dugout canoes’ motors.

I always find it difficult to place myself in such hectic environment. Where to stand to not disturb them? Am I allowed to take pictures? Am I allowed to get that close? But after a few smile here and there, you realise they actually don’t care as long as you don’t put yourself into a risky situation.

We arrived in the middle of the afternoon at the entrance of the abandoned Khmer Rouge airport that I wanted to check out. A soldier with an AK47 was guarding the entrance so I was happy that Kosal could negotiate directly in Khmer. For 1$ we could get in with the tuk-tuk, on condition we did not take any pictures inside.

Kosal explained – although I knew most of the story – that the Chinese supervised the construction of this secret military airport during the Khmer Rouge era. They only used this airport to export rice and gold from the area as Pol Pot never had any air force, nor had the wish to develop one.

According to Kosal, history is repeating itself today as big Chinese corporations are controlling all the mines and most of the rice fields, leaving the local community without jobs. As a consequence, most of the young people are fleeing to Phnom-Penh or Thailand, leaving a bleak future for the upcoming generations. It is true that I didn’t meet anyone from my age in most of the villages we crossed today.

Day 3 – Siem Reap

Bus to Siem Reap. To my surprise, I was alone with a mother and her kid in a small minivan so I laid down at the back and listened to Modern Methods For Ancient Rituals from The Transcendence Orchestra while contemplating the beautiful landscape.

A radical change occurred after four hours of driving and a lunch break in Battambang. For some reason I had to continue the trip in a Toyota with nice people. The driver and a kid in the front, myself with three other adults and two babies in the middle, as well as two grandmothers in the back, squeezed between boxes. It didn’t make sense at all to me but apparently it did for the driver, who, driving like a maniac, picked up and dropped packages every 20 minutes and listened to K-Pop very loud.

If this trip was made to spark my creativity it at least challenged my patience. Such an intense afternoon.

My first impression of Siem Reap, the popular resort town and gateway to the Angkor region, was not that good really annoying tuk-tuk drivers, people trying to sell me drugs and drunk tourists in the street.

Luckily I still had time before dusk to check the Center for Khmer Studies with the hope to find some documentation about the Phleng Arak.

Day 4

Day 5 – Preparation

Bus to Kampong Thom. It was very stop start as we collected motorcycles, luggage, wooden stools, 12 bags of rice.. At precisely 12pm, we stopped for lunch while we were only five kilometres away from the bus station. I realised at that point that every bus I took during this trip stopped precisely at 12pm. I learn later that almost nobody takes any transport between 12pm and 12:15pm because ‘bad’ spirits are out, so it is advised to stay somewhere calm.

In a cafe I meet up with Emily Howe, a PhD candidate in ethnomusicology at Boston University currently researching the relationship between music/sound and development in Cambodia, including Phleng Arak. Later in the afternoon, we met with Raksmey - the person who arranged the recording session with the musicians. He is an anthropologist and administrator of the Kampong Thom Department of Culture with a general interest in documenting heritage in Cambodia.

This project is particularly important to him because the musicians are from his home province and because they are all quite old. As he has noted, it is quite urgent to document the local practices before it is too late. He hopes that the recordings and photographs will raise awareness in Cambodia about this dying ritual.

Emily wants to understand how this "functional" healing music is understood and practiced amidst large-scale societal changes including the rise of Western medicine.

The musicians were curious about recording and hearing their music as listeners instead of as performers, although some of them definitely didn’t want to record particular songs for various reasons.

After a good dinner with them, I spent my whole evening preparing, testing and double checking all my gear, both at ease from the conversations we'd had and very excited for the day to come.

Day 6 – Recording

We arrived at one house on stilts where the musicians were located. I didn’t really introduce myself because I was already busy setting up the recorders and looking for the best spot to photograph them. They actually joked about it at some point, asking if I was mute or something. Haha. Something I should definitely improve for the next time.

The conditions were quite difficult, both in term of acoustic and light, but if I take an objective look at the result, I think we did pretty well.

We used two microphones, one hanging from the ceiling facing downwards and the other one on a tripod facing upwards in the middle of the circle formed by the musicians. We recorded the whole afternoon, including the discussions and jokes between the songs.

The band was composed of a total of six men. Four musicians were playing the Sko Dai, a relatively small drum made of jackfruit wood and covered with snake or lizard skin. One of them was also the main singer. The fifth musician was playing the Tro Khmer, a bowed three silk string instrument made from a special type of coconut covered on one end with snake skin. And the last musician was playing the Sralai, a sort of small oboe made of palm leaf.

Musically, I don’t really know how to describe it as it sounded like nothing I have heard before. I am also not sure if comparing it to other music would be a good way to do it. What I noticed though is that the Sralai was always starting first, usually followed by the Tro Khmer and then the Sko Dai.

We spent the whole afternoon there, listening to this beautiful and transcendental music, forgetting all notion of time and space. Just there, present, sharing a special moment. The atmosphere in the room was magical; we could only talk with glances and smiles and every gesture was carefully evaluated and considered in order to avoid to screw up the recordings.

To be honest, I now have more questions than before about my project and practice, but that's also the best part of such an experience. It challenges your assumptions and ideas, confronts them with the reality on the ground in within an unfamiliar environment.