In 2005, after the deaths of two teenagers during a police chase, huge riots erupted in France’s banlieues. Photographer Simon Wheatley visited Paris and soon joined other journalists on a bland media tour. Magnum offered him the chance to visit France’s fourth largest housing estate, on the outskirts of the picturesque city of Blois. Seeing an opportunity to go deeper and paint a truer picture of the mood of the nation, he made multiple trips to the area of his own accord and extended the project, which has now become the book “Always and Forever There.” He tells Dalia Al-Dujaili how he wanted to tell the side of the story not often told—to portray France’s “institutionalized marginalization” and to shine a different light on an often forgotten, misrepresented section of the country’s population.

Blois, central France. A Gothic cathedral stands tall and proud, surrounded by chateaus filled with ornate decor and historic artworks of late kings, and lush gardens to rival Eden are set along the river Loire. It’s a picturesque city, one we might call typically French. What Blois doesn’t reveal is the country’s problematic approach to housing the country’s migrant populations, that 20,000 of its 50,000 inhabitants live in the fourth largest housing estate in France just a kilometer away.

On October 27, 2005, after the death of 17-year-old Zyed and 15-year-old Bouna resulting from a police chase, France’s suburbs, or banlieues, erupted in protest against the country’s systematic police violence and racism. Simon Wheatley didn’t intend to stay in France when he was sent on assignment to capture the mood of a nation characteristically in protest towards its authorities—he jumped on a train after hearing that no other Magnum photographers were documenting the estates at the time.

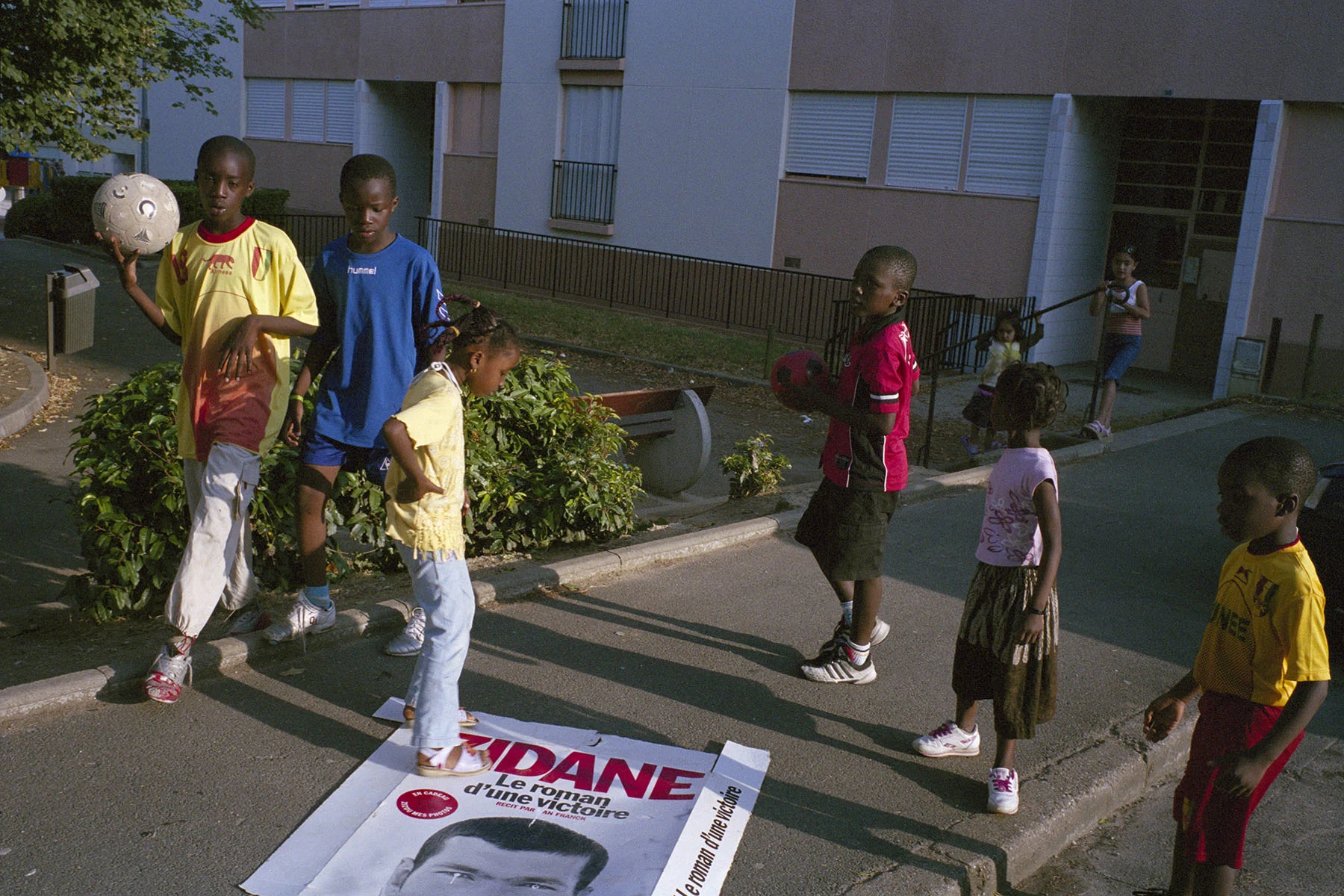

“Always and Forever There,” his book published late 2023 (18 years after the photos were taken) is a tale of youth pushed to the margins of French life, as Simon says in the book, “lumped on the edge of town.” Wheatley photographed Blois and its inhabitants in 2005 after being commissioned by Time (via magnum). “[In Paris] it was a bit of a media tour,” he says of when the journalists first arrived. “We saw some burnt out trucks and cars. I made a few photos but it seemed like a very pointless exercise. It was almost tourist journalism.”

After the editorial director in the Magnum Paris office asked Simon if he would go to Blois, he saw it as an opportunity to delve deeper. He met some youth workers on his first visit, and asked to be introduced to more youth from the banlieu. “[The youth worker] met me and he said look, I’m going to [...] drop you in and that’s it from there, you’re on your own,” he recalls. Some of the first images Simon made were of a group of boys in a basement. The notable scene shows one boy gazing up at his friend on a motorbike, his partially-covered face cinematically illuminated by the red brake light. The young men were “maybe a bit intrigued and humored by my presence,” remembers Simon. He owes the intimacy of the images to his nonthreatening demeanor and sensitivity; the frame invites the viewer to be involved, almost as if we might be friends with these boys, or might have grown up with them.

After a video of the photographer dancing to one of the young men’s Algerian wedding music circulated around the estate via Bluetooth, the French youth, who were already tense at the way their image was being maligned throughout French media, perceived Simon in “a more humorous way...I have to be forever thankful for Algerian wedding music,” says Simon.

Simon’s images are informed not only by the young people at the heart of these stories but also by the spaces they inhabit. What Blois demonstrates is, as he says, the institutionalized marginalization prevalent in France—the pushing outwards of the working class, immigrant communities to the suburbs, the ghettoization of their neighborhoods by the ruling elite.

Housing most of France’s North African, Arab and Black communities, these banlieues, such as the one backdropping the iconic 1995 anti-establishment film “La Haine,” have historically seen police brutality against ethnic minorities. Following the riots of 2005, there has been little change in France’s mood towards immigrants and their youth, especially the violence facing young men of North African descent, despite regeneration efforts from the government targeted at the underserved areas. Only last year, Algerian Nahel M., 17, was shot dead by police in Nanterre, an estate near Paris, catalyzing yet another wave of protests calling for “justice pour Nahel.”

Although created in 2005, Simon didn’t approach the work as a book for another 18 years. “I pretty much fell out of love with photography or my practice after the French work, especially when it was published,” he admits. After Paris Match ran what the photographer calls a “sensationalist edit” of the images from Blois, he felt he had disappointed the people in his photographs, people whose trust he’d gained. “That was very soul-destroying,” Simon tells me, “I just didn’t want to do that work anymore.”

Rather than taking a necessarily narrative approach to the sequencing and layout of the images in “Always and Forever There,” Simon opted to use the pages to reflect time passing in Blois. “It takes time to understand what you’ve done,” he explains, “to really look at your contact sheets and not just to locate the individual frames that are the good photographs, but to look at them as a whole experience.”

You’ve got to go out into the world, not thinking about the result. You just exist, you listen to people and you feel the story.

It’s his ardent piece of advice to young photographers; to not set out to make a book, but rather engage in the process of making art first. He believes that “when you set out to make a book before you’ve taken any photographs, there’s something inherently corrupt about the process. You’ve got to go out into the world, not thinking about the result.” Especially for photographers engaged in documentary and street life, the real work is done when the camera is facing away, “and you just exist, you listen to people and you feel the story. That informs your photography afterwards.”

From Marseilles to Paris’ banlieues, France has a flourishing migrant population who rarely get the chance to tell their own stories. Through the retrospective body of work, Simon hopes that this project will allow us to reimagine the stories told about immigrant youth in France, moving away from violent stereotypes and towards a youth not only integrated into French society, but also not villainized for being authentically themselves.