For first generation Pakistani-American artist Sabreen Jafry, a sense of belonging has long been elusive, but also part of what informs her work. Following a trip to one of Pakistan’s most famous buildings, these feelings were brought into focus. Writer Elliot Watson meets Sabreen to talk shifting perceptions of Pakistan and finding a home in New York.

“Imagine if Times Square was deserted…,” New York-based artist Sabreen Jafry is drawing an analogy for her experience photographing the Faisal Mosque in Islamabad. “There are places meant for thousands of tourists but it was just us, and maybe a group of boys or girls on a school trip.”

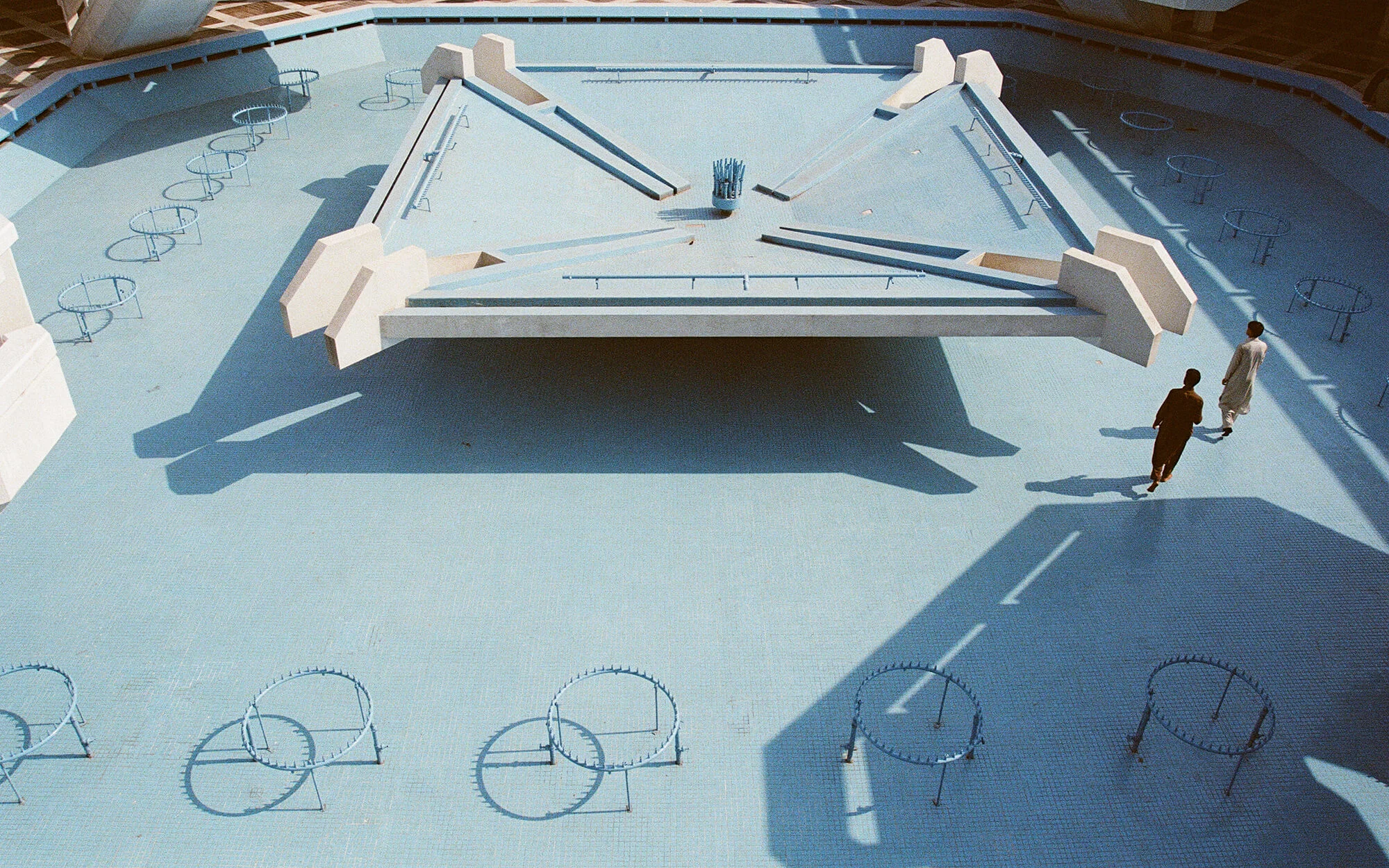

Faisal Mosque is one of Pakistan’s most famous buildings. A riveting example of contemporary Islamic architecture, it recalls more a spaceport in a science fiction movie than the traditional assembly of minarets and domes. Were it situated elsewhere in the world it would likely draw tourists by the busload, debating its irreverence for architectural norms, photographing its angles and being profoundly moved by its scale.

Sabreen’s photograph shows a young boy in shirt and tie descending one of the mosque’s many sets of broad steps, the abstract shapes of the building cutting a stark outline against a mid-blue sky. A glimpse of the Himalayan foothills beyond the city limits completes the picture. It’s just as the artist describes, “eerie, picturesque and very surreal.” In this photograph at least, Faisal Mosque remains a numinous experience largely unfulfilled.

This place that no one visits is beautiful and welcoming.

The photograph is part of the series Ghalat Femi, images collected on a three-week trip to Pakistan. From tradesmen hand-dyeing garments, to cerulean oceans, truck drivers with cigarettes and gatherings of school girls holding cell phones, the images paint a vivid picture that mounts a compelling challenge to established Western narratives about Pakistan. “The biggest misconception of all is that they are living very different lives to us. They’re not,” Sabreen says, highlighting the day-to-day routines captured in Ghalat Femi as symbolic of an overlooked affinity between civilians across cultural divides. “The underlying feeling was that people are just living their lives no matter what turmoil or chaos is happening politically, the same way we are here in America.”

“There’s this idea that people are anti-American and in some ways extreme in their beliefs but the truth is that, just like any religion or culture, there are very liberal people and very conservative people. What I wanted to portray in this series is that this place that no one visits is beautiful and welcoming,” Sabreen explains of the project’s intention to alter perceptions of a country that cuts a turbulent figure in the global news cycle and a largely absent one in travel brochures.

As we continue to debate the veracity of domestic news or simply remain consumed by its relentlessness, critical evaluation of reports from elsewhere is increasingly less likely for anyone without a specific interest in global politics. In the case of Pakistan, repetition of negative news stories has transmuted into a mainstream, myopic prejudice that has rendered its international tourism industry almost obsolete. According to The Nation, Pakistan’s largest English language newspaper, fewer than two million tourists entered the country last year; many of whom were thought to be members of the global diaspora. The lack of visitors (and therefore visibility) deepens mistaken beliefs. Sadly, the problem seems likely to worsen given the recent renewal of decades-old tension with India over the disputed territory of Kashmir.

“You never see anything positive about Muslim countries and specifically about Pakistan in the news,” says Sabreen, “But there are so many Muslims doing amazing things in music, sport, film, medicine, everything.”

Everyone knew I was American. They could see by the way I walk.

Art has the capacity to add nuance and compassion to that one-sided conversation: “It humanises this country that is very elusive and is in the news. There are peaceful and wonderful human beings who live there. There is beauty in everyday life.” The responsive and curious lens of Ghalat Femi finds tailors at work or a fabric seller draping their wares over a brand new Toyota hatchback. Subjects are uninterrupted, captured in their natural rhythm of work, commute or worship. Compositions are observed and naturalistic, betraying the photographer’s use of film to embrace spontaneity and prize intimacy over idealism.

Implicit in its purpose to realign its viewers’ perception of the world’s second largest Muslim-majority country is Ghalat Femi’s contribution to Muslim-American identity. The paranoia and ignorance imparted by post 9/11 political rhetoric and stoked by Donald Trump remains insidious, especially outside multi-cultural coastal cities. Art is a vital counteracting force: “In New York City people are liberal, but for the Muslim in Texas things are going to be different. At any point in time you can find yourself the person who represents your whole community, your whole religion or your whole ethnicity. That’s a heavy burden that looms over all of us,” Sabreen explains, “As Muslim-Americans we’re all trying to portray a positive view. Five years ago, perhaps we weren’t comfortable calling out racism or misinformation but now people are much more open to providing and receiving education, people are more open to changing their perceptions. Photography is a visual aid in that process.”

On a personal level, creating the project on her first visit to Pakistan allowed Sabreen to contextualize her own experience as a first generation Pakistani-American. “I hoped I would belong and I did blend in in many ways,” she says, “I dressed the same, I spoke the language. But at the end of the day, everyone knew I was American. They could see by the way I walk.”

The experience cultivated a sense of dis-belonging, “There I was, the American girl, and here in America I’m the Pakistani girl. I realized I don’t really belong anywhere. As first generation immigrants there’s this sense of being neither here nor there. It’s why I like New York, everywhere you go you’re meeting people from somewhere else, whether it’s an Uber driver or on the subway. We all have that shared experience. This is the city of the displaced.”