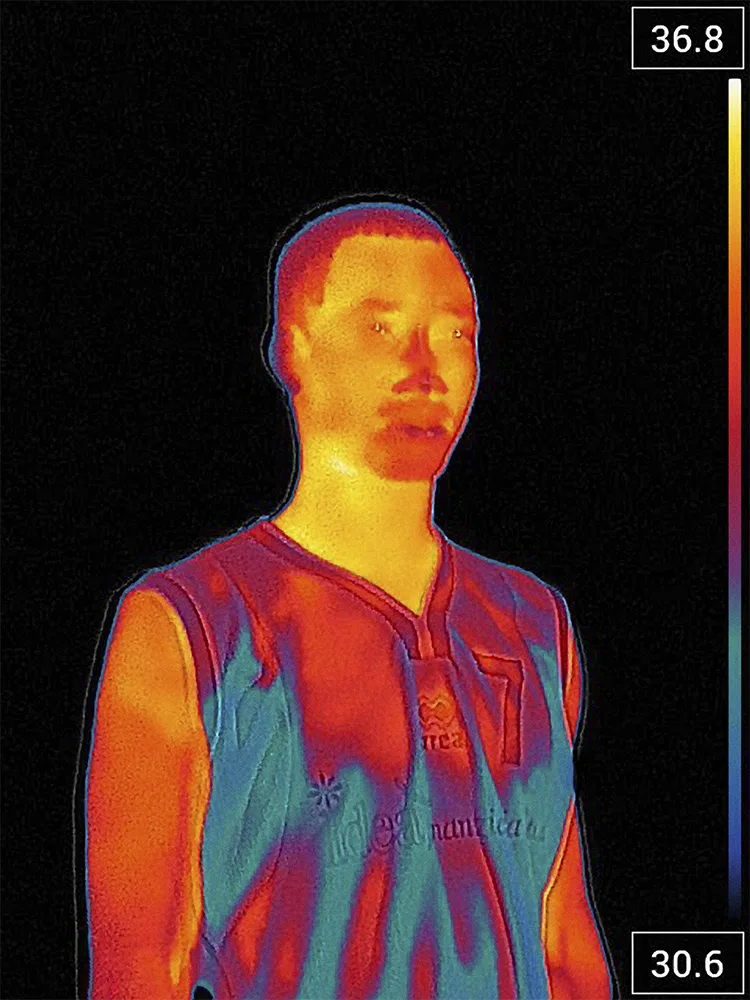

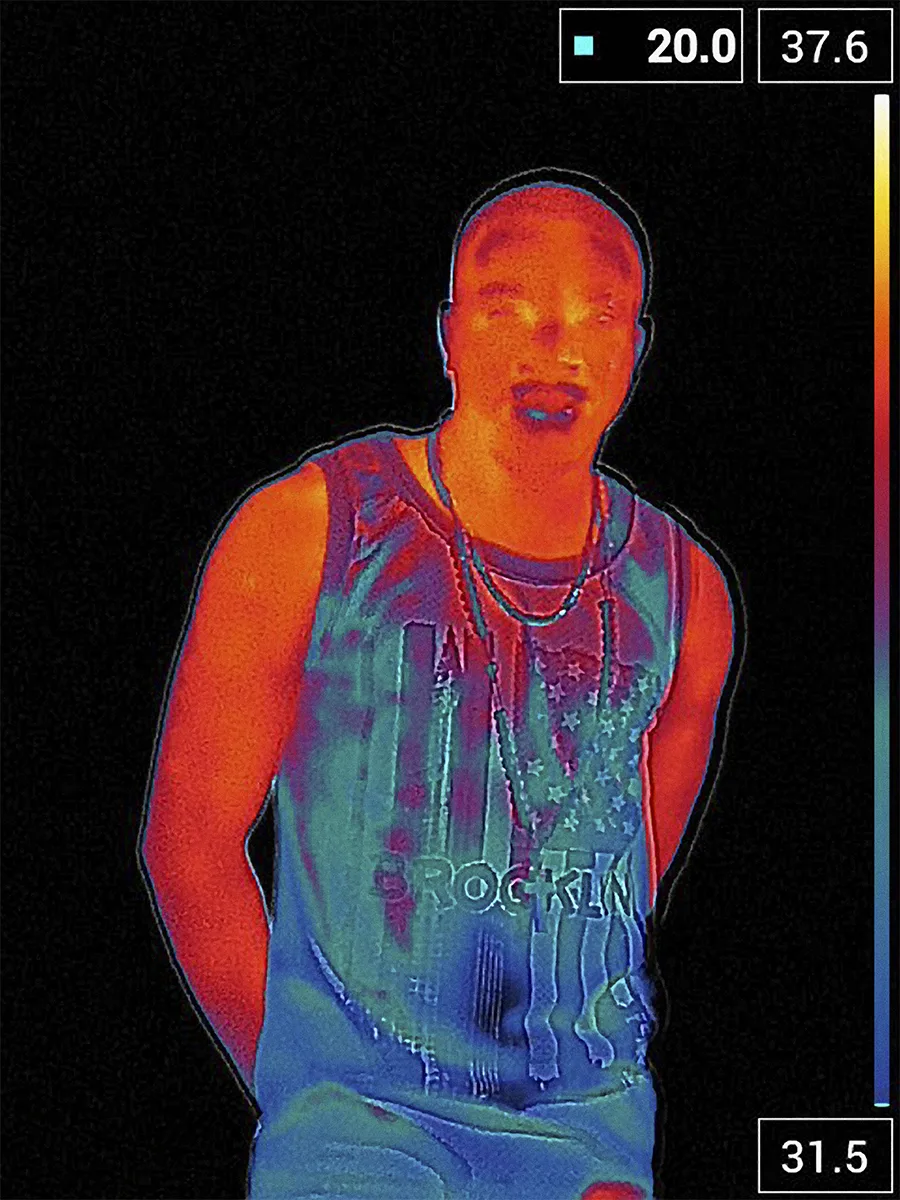

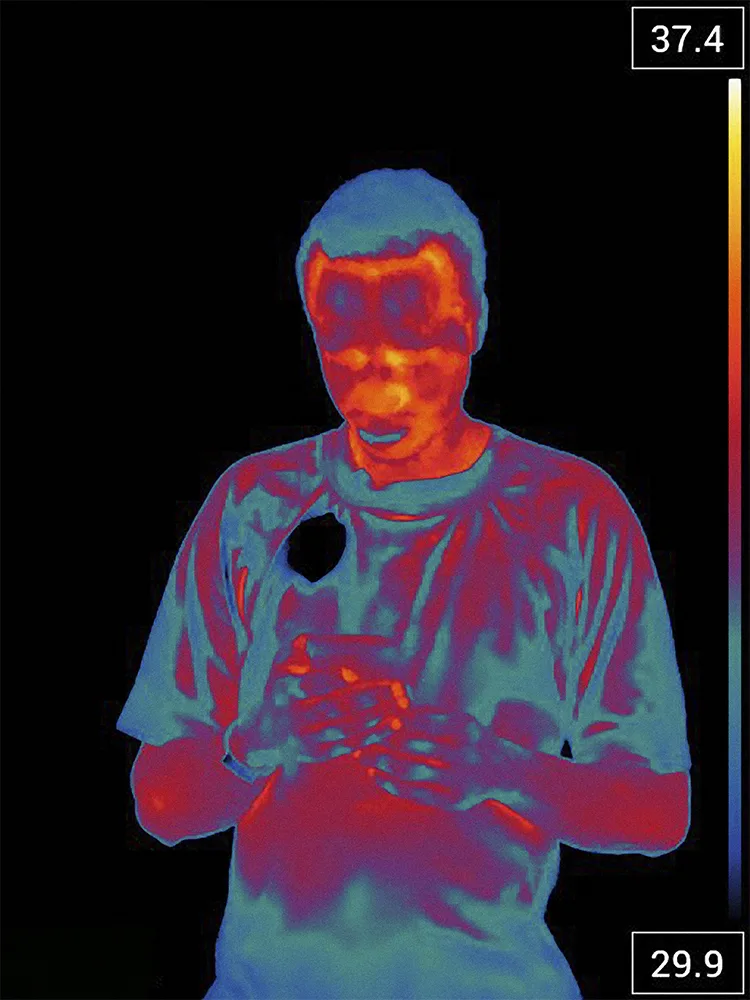

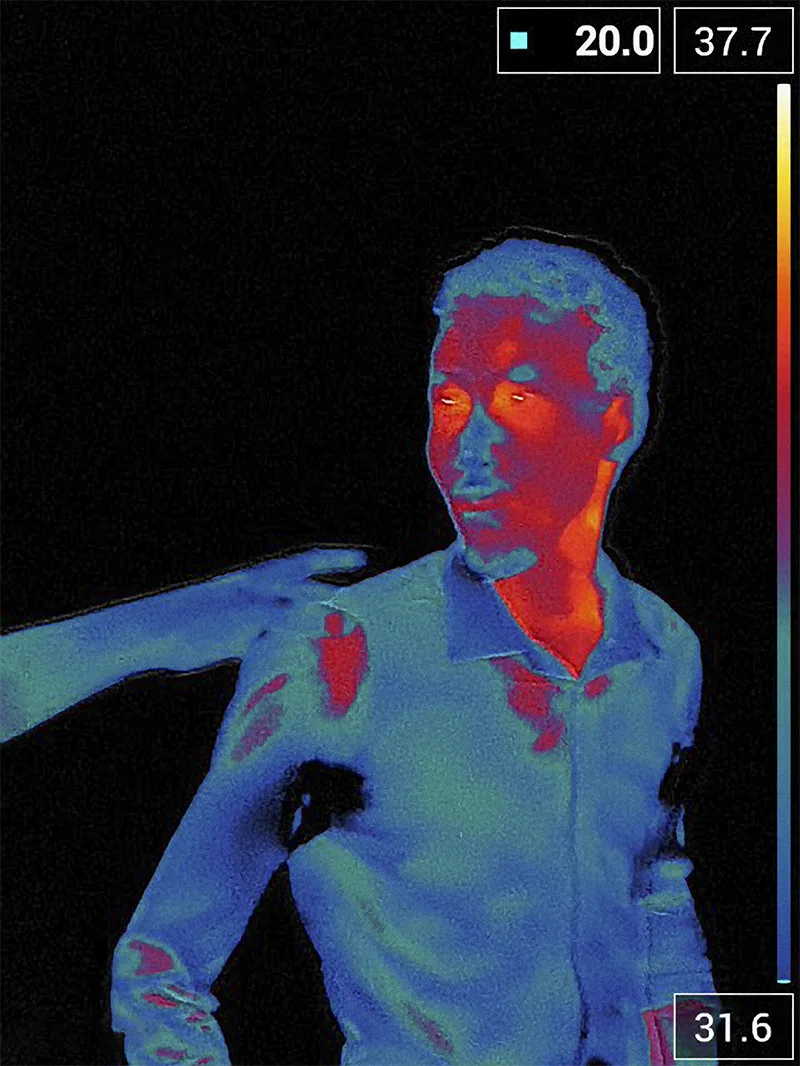

For her series The Warmth, Italian photographer Roselena Ramistella documented the stories of refugees and asylum seekers in Sicily with a thermal imaging camera. As the hues of their bodies respond to questions about their pasts and futures, her project endeavours to record the inarticulable.

In 2019, Italian photographer Roselena Ramistella started a project documenting the emotional language of refugees and asylum seekers, whose journeys had led them to Sicily, Italy. Based in Palermo, Roselena reached out to participants through SPRAR, an Italian governmental initiative that welcomes and houses young forced migrants from different parts of the world. “There are a lot of projects that speak about immigration and asylum seekers, and I’ve approached the issue a few times myself,” she explains, “but this time I wanted to dig deeper”.

The resulting project is The Warmth: a series of videos capturing the changing pigments of people’s faces and bodies as she asks them questions about their lives and experiences. “I was looking for a new narrative trying to follow roads not taken; I asked myself if emotions had a color and if I could see them” she says. It was this idea that led Roselena to use a FLIR thermal imaging camera – a device which detects infrared energy, or heat, and translates it into visual images.

Through its lens, we are able to observe a body’s response usually hidden from sight. For Roselena, “the chance to see the color of these people’s faces changing according to the impact of the questions upon their lives,” was the key to seeing “emotions in all their authentic strength.”

I asked myself if emotions had a color and if I could see them

The images in this article are portraits taken as part of an ongoing project for Roselena, which also included film footage of the conversations she had. The deep hues visible in and around the subjects are the result of their body temperature changing as Roselena interviewed them. Different tones appeared and moved around their bodies as the subjects recalled details of their journeys and traumas. The colors would shift when they spoke of their hopes and loved ones, favorite music and passions. “I wanted to understand if emotions could be frozen in time,” she says.

Sitting beneath lights, Roselena asked each person a series of questions and invited them to ask her whatever they wanted in return. The anonymity provided by the thermal imaging camera enabled those being filmed to speak freely. “Words came out like a river in flood,” Roselena remembers. The questions she asked were pulled together based on those of the Territorial Commission, the designated institution responsible for the granting of international protection to asylum seekers in Italy. Their tone is generally “technical, cold and detached,” Roselena says, noting that it was important for her to instead ask questions rooted in warmth and empathy.

“I asked a boy if he had taken something with him during the journey, and he told me he brought a photo of his mother with him,” she says, “a hint of a smile appeared on his face, when just before he was anxiously telling me about the abuse he suffered in Libya.” Roselena’s other subjects include young women and men from Nigeria, Gambia, Mali and Senegal, each with their own histories and aspirations. Through their conversations, Roselena wanted to capture whole spectrums of emotion, not just records of persecution required by the state in return for their protection.

In some ways, the stripping away of somebody’s features feels reductive – the seeming elimination of the individuality of a person. But here the reduction is about accessing and showing something that is unreachable through language. An attempt to photograph the unphotographable; to capture and visually articulate emotional transformations in a person’s body. To Roselena, documenting people in this way serves to “enhance their individuality” and shows “how the root of emotions is the same for every human being.”

Words came out like a river in flood.

In the context of asylum seekers and refugees, where reduction to a faceless mass feels increasingly the norm, this project illuminates the humanness of its participants while raising questions about the tropes so often applied to migrants and migration more broadly. A vernacular of surveillance, the technology of thermal imaging is more commonly used against forced migrants as they exist in a beam of detection few of us can imagine. The Warmth evokes ideas of detection not in response to evasion or suspicion, but instead to expose the unguarded emotions of individuals, removing any barriers between us as emotional beings.

More and more, the living bodies of asylum seekers are being relied upon as terrains of truth. Maps of scars, both physical and mental are required by states to prove somebody’s story, their words not enough on their own. The Warmth uses them only to bolster the words spoken, placing emotion and empathy at the top, where it is so often lost.

Just as no two images in the series are the same, the personal testimonies of each of the subjects are unique to them. As biological responses are brought to the fore, the viewer is encouraged to remember that each is just a person, home to experiences and traumas they alone have felt and metabolised – communicated to us through heat and color as they choose to recollect and share, in the hope of a better life.

Anonymity enabled those being filmed to speak freely, but Roselena “didn’t want any veil. I wanted their answers to not be filtered by anything.” By stripping it all back, leaving just the words of individuals accompanied by pigmented testament tracking their emotions like a mood ring, it is Roselena’s hope that people will be encouraged to listen in a new way and hear them solely as people, navigating their feelings and emotive reactions to memory and experience just like the rest of us.