By any measure, Paula Scher is one of the most important graphic designers in the world. A partner at the famous Pentagram collective, she creates visual systems for brands and organisations ranging from Microsoft to the New York City ballet and she is particularly renowned for using personality-infused typography.

When Netflix launched its recent series Abstract: The Art of Design, Paula was one of eight designers from across the creative spectrum chosen to be profiled.

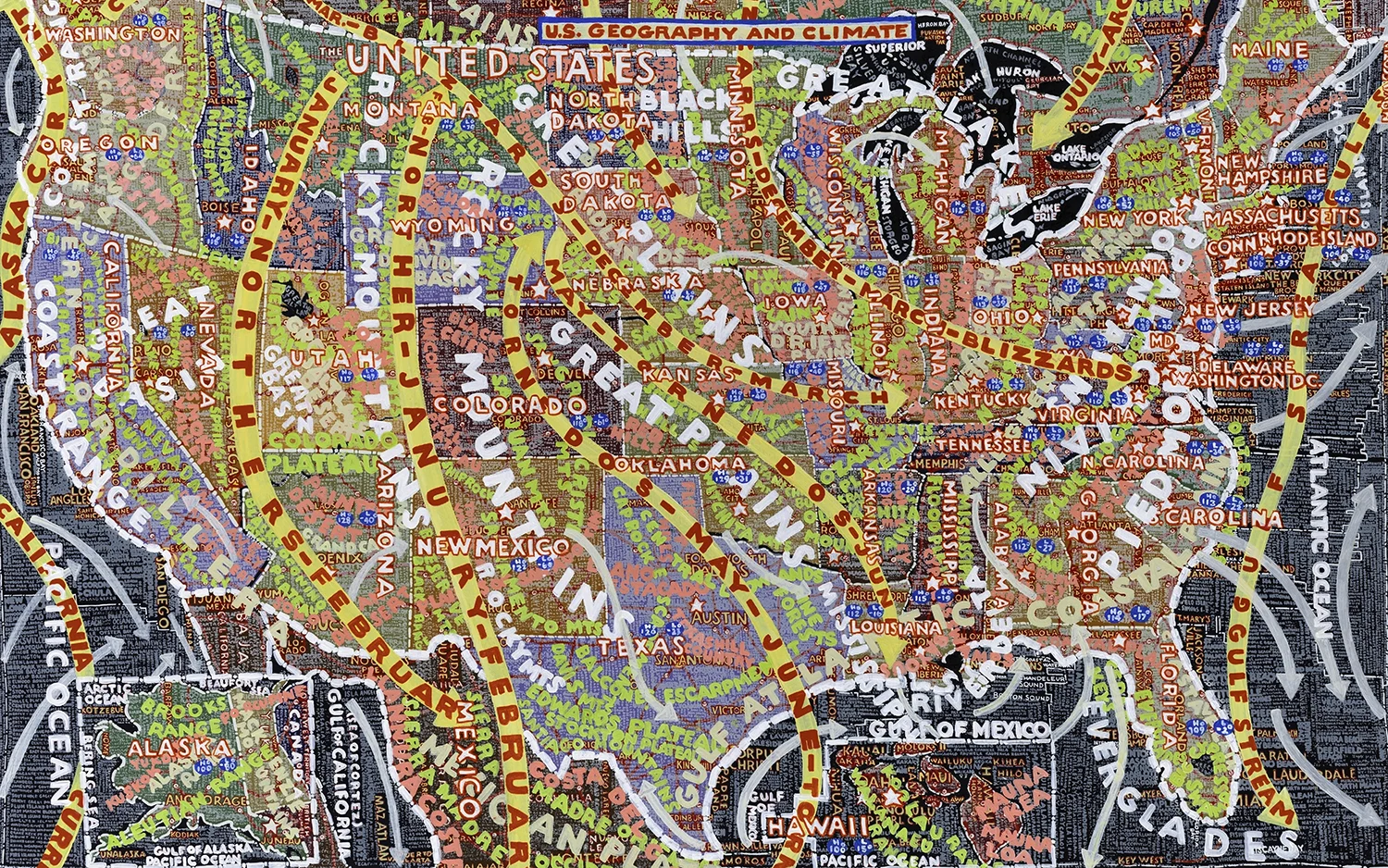

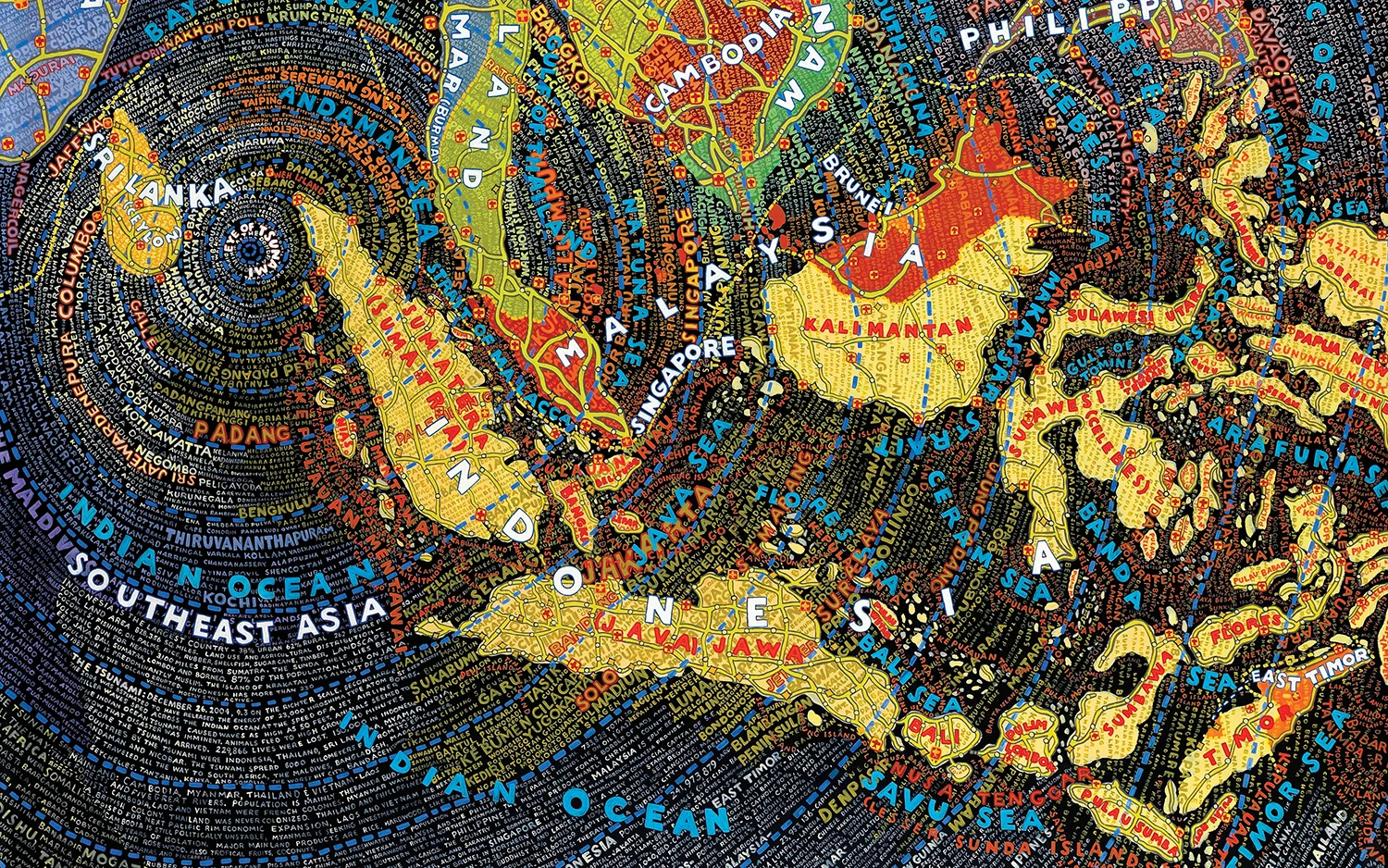

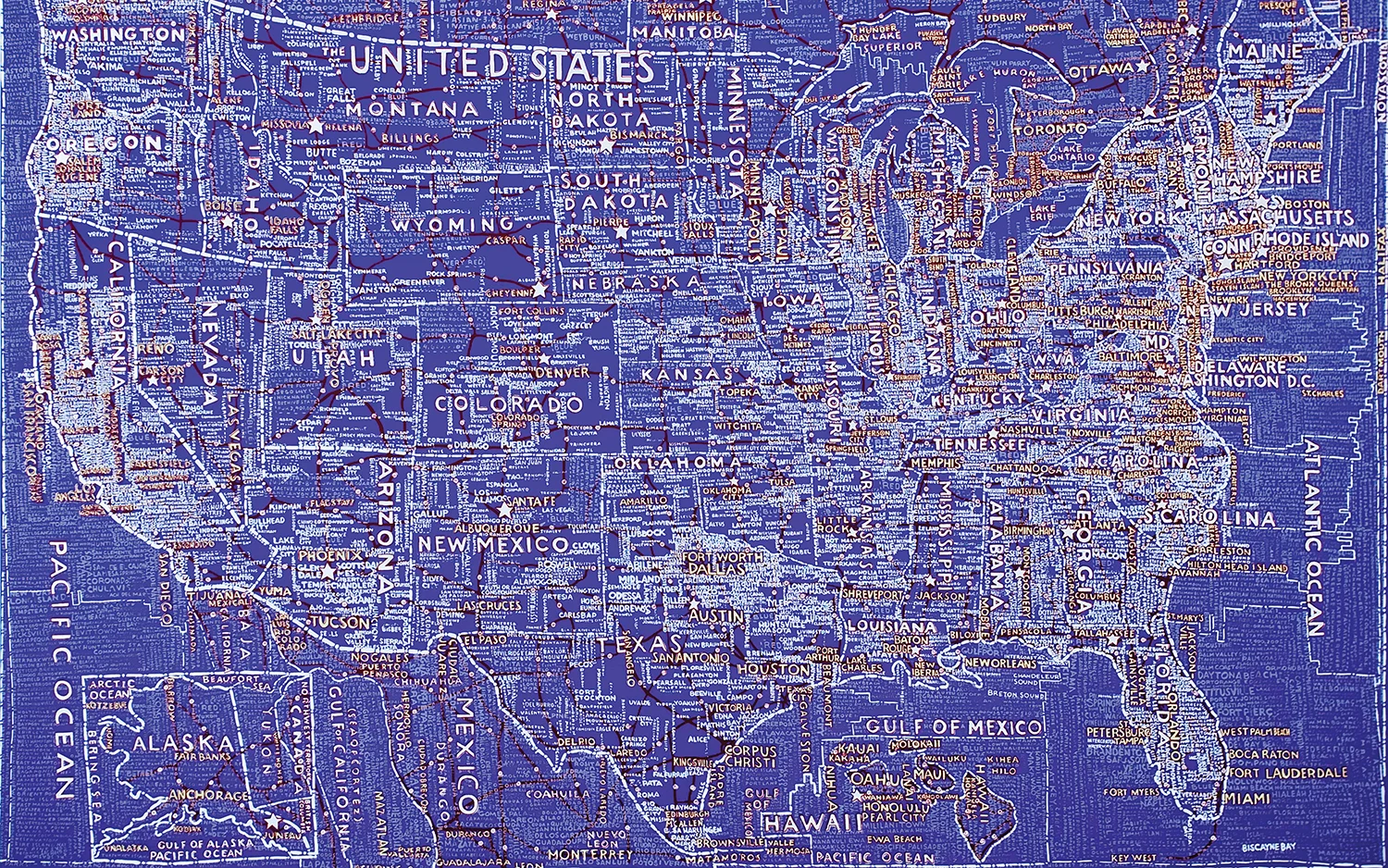

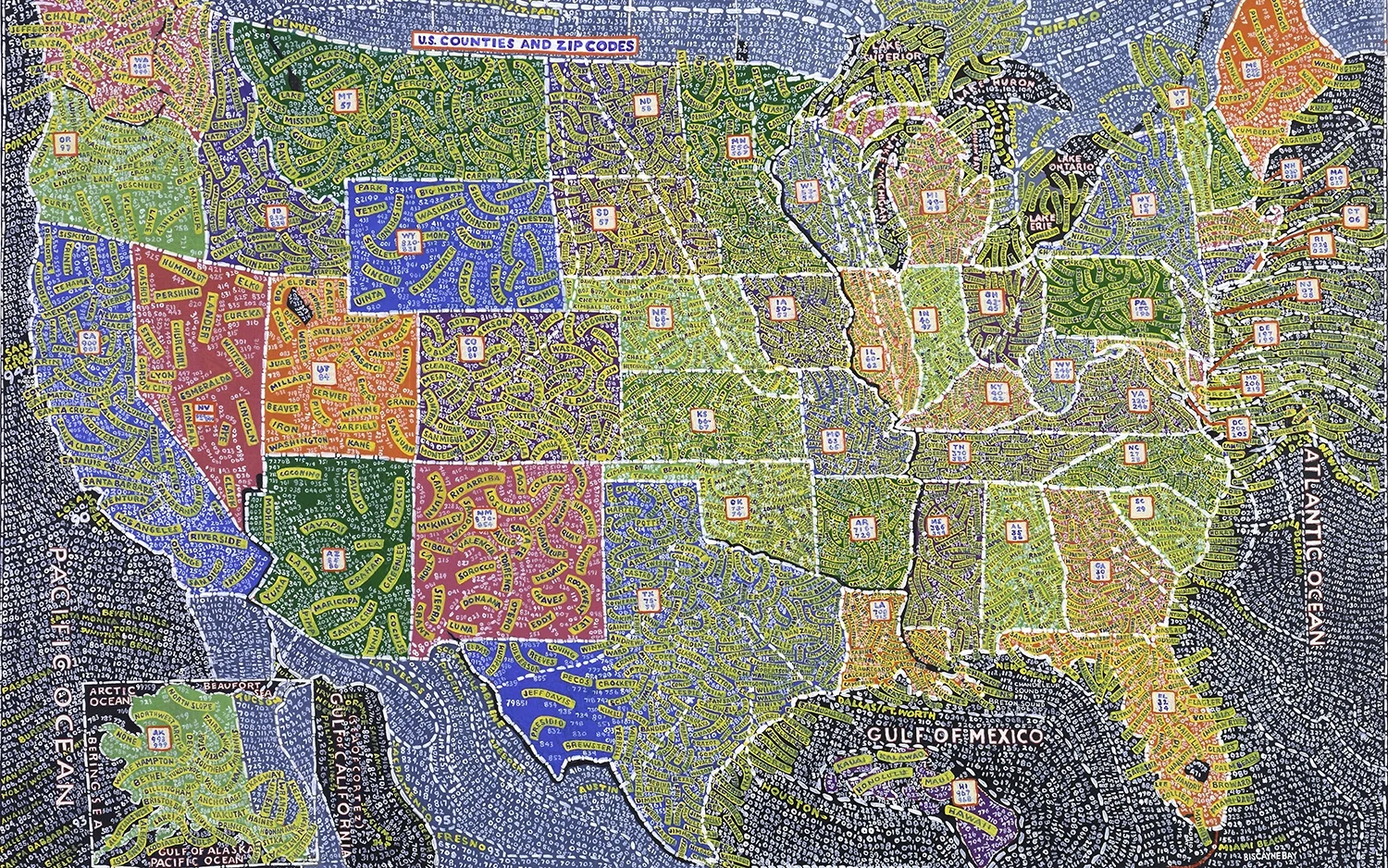

And as that documentary showed, Paula has two distinct professional passions. On the one hand there is her design work – the clients and the deadlines and the presentations that revolve around New York, a city whose visual energy feeds off. And on the other hand there are her paintings – huge colorful maps which she creates in the calm and the quiet of her house in the Connecticut countryside.

“It’s the tactility of painting, the ability to manage and manipulate color that gives me so much pleasure,” she says. I paint in acrylics, so the color is built up in the series of levels of layers of information. Then there is the excessiveness of the information and the things that I learn when I am painting. They depict overall truths and it’s an amalgamation of information that in its volume creates sensibilities about places.”

Obviously when painting she draws on many of her design skills, her use of color and space and visual communication skills. But in other ways the paintings provide a contrast to her design life.

“One is solitary and one is social. One happens very quickly and one happens very slowly. A design project has a beginning, a middle and an end, but a painting is never really finished. Sometimes you just stop, but there is always so much more that could happen, could change. And when you are finished with a painting, you don’t necessarily get a cheque.”

That’s not to say that the painting is always a smooth process.

“There is always a part in the middle where I think I am never going to see the end and I have made a terrible mistake. I just work through that. Because I have experienced it so many times, I kind of welcome it. I know there is a point where I figure it out, where the discovery gets made and there is some emotional connection that I begin to have with the material.”

The paintings may show the whole world or part of a country (often the US) and they can bring to life something very specific – global flight paths for example, or the ZIP codes used in the US postal system. But they are always maps, and her interest in cartography goes back to when she was little. Her father was a civil engineer who designed a device to correct how the curvature of the earth affects aerial photographs.

“He was obsessed with accuracy, but he knew there was absolutely no such thing as accuracy,” Paula laughs. “He showed me a picture of where we lived in Maryland and the driveway looked wrong. That’s what I learned as a kid. I heard words like ‘distortion’ and to me that meant maps were lying.”

There is always a part in the middle where I think I am never going to see the end and I have made a terrible mistake. I just work through that.

She describes the creative licence she takes as “abstract expressionist information” and we the viewers are complicit in what messages we choose to take away from them. Having said that, her exhibition of US maps last year ended up ringing a lot of the alarm bells that the experts missed when ruling out a Trump victory. Her voice hardens as we discuss the election results and she reels off statistics about the electoral college and gerrymandering and how some voters count more than others.

“Wyoming has 650,000 people and two senators and New York has 19.7 million people and they have two senators. What does that say to you about democracy?”

When she was making her paintings of the US, she was aware that the country was organised irrationally. “I saw that at the time. I had an acute sense of what was going on with the population,” she says.

The Netflix documentary shows her at work on the paintings and in the film she reveals that rather than listening to music as she paints, she plays old movies in the background. She likes to speak the lines along with the actors, and in the documentary this is neatly split-screened with the clips of the famous movies she quotes from. It’s one of several clever visual effects in the film, although Paula wasn’t always at ease in front of the camera.

“I found the whole thing mystifying,” she laughs. “They did a series of interviews that felt fairly typical. Then he kept making me walk up and down the stairs at Pentagram and I see the damn thing in one shot! He must have had me walk up the steps about 15 times. But there were things in the film I just loved and was astounded by.”

Creatively speaking, it’s not often that Paula cedes control in this way. Whether as a designer or a painter, she is usually the one calling the shots, but in this rare role she knew better than to meddle. “They were absolutely right not to show it to me in advance,” she says. “I’d have been horrible!”