From posters to murals to book covers, Dutch artist Parra has an eye-catching visual style that lingers long in the memory. When we got the chance to help him make a giant rabbit sculpture for Amsterdam music festival Appelsap – which he calls Leave me alone, but put me on the guestlist – we leapt at the chance.

And we knew just the man to do the interview – another Dutch creative who goes by only one name. WeTransfer founder Nalden sat down with the artist to chat about the new piece, the Amsterdam creative scene and their shared love of skateboarding….

Parra:

Graphic design, flyers, that’s where I started.

Parra:

It wasn’t actually a choice I made. In 2005 an ad agency asked me for an exhibition. They had this tiny downstairs exhibition space in London. So then I scraped the text from a whole bunch of posters and flyers and just magnified the images. We had posters printed really cheaply and we sold them even cheaper. That’s how it started. I was scouted by Big Active and suddenly I was an illustrator, which I didn’t want to be. I did a load of weird assignments.

Parra:

This is often what I find most difficult about interviews, knowing how everything started. It really only started to become clear quite a bit later, around 2009 or 2010. Like, I can do this. And I’m going to do this. And I’m going to take it seriously. All those things we were talking about before, it’s all too blurry. It was all mixed up. I got amazing assignments. I did stuff for Nike. But I also had to do really stupid assignments, which I’m not even going to mention. I chucked that hard disk out.

Parra:

I can’t find it online, seriously. The great thing was that this was all before the financial crisis and you actually got paid really well as an illustrator. You got a one-off payment for your drawing, and then you got royalties too. And that added up pretty quickly, but then I thought, you know what, fuck this, I’m quitting.

Parra:

No. The other things were already casting their shadow over the commissioned work.

Parra:

You’d see ten people wearing it at a party, but that was it.

Parra:

Yes, that was in Holland, of course. And I was always in a hurry, everything had to be done quickly. You end up doing a whole lot of things and I realized I was doing crappy stuff. And then around 2010…

Parra:

After I won that Amsterdam art prize. That felt different because I’d never received validation before. Certainly not in Amsterdam and not in the Netherlands. I suddenly felt like, oh, shit, people are paying attention.

Parra:

Exactly. Rather than in streetwear or in the world of small galleries.

Parra:

I had a lot of lucky breaks too.

Parra:

Absolutely. I started out in the days before the internet was really a thing. I mean, in the old days I had an email address and you’d get, like, one email a week.

Parra:

People didn’t even have websites showing their work. There was time to hone your skills. Now people put things online so quickly, even if it’s bad, and then you’re going to get butchered. But then Amsterdam was still free rein. You could do whatever you liked, because no one knew what was ‘out there’...

Parra:

Mediocrity has always been part of it, I think. I mean there were stupid flyers in the old days, right? But you can just tell if someone’s good at making something, that they’ve put in the hours. You can just tell. Even if you have talent, you’ve still got to put in the hours.

Parra:

Yes, he’s a real artist, who makes things every day, his own work.

Parra:

No. I’m still kind of half applied. In Holland it’s such a big deal to call yourself that. The word artist still has pretty intense connotations here, right? It sounds really arrogant. In America it’s a much more relaxed word – it could mean all sorts of things. Here an artist is expected to have a studio, people want to come and visit. My dad’s an artist. He has a studio. I’ve never perceived myself that way, but I do deliver the work of an artist.

Parra:

Sure, he does. He thinks what I make is really cool. But he works straight on canvas, whereas I spend a long time messing about with drawings…

Parra:

I do still work on paper but I transfer to iPad Pro pretty quickly now. I used to use tracing paper and that was really messy. Now it’s digital tracing paper.

Parra:

I project it. For me the most important aspect of the canvas is composition. And if that isn’t right, then I can set everything up manually, but it doesn’t feel right.

Parra:

There was a book about Hieronymus Bosch when I was a very young kid. The medieval painter with all those creepy drawings and paintings. Hieronymus Bosch painted a sort of hell, I used to love looking at that. It was my dad’s book. And I think I secretly stole everything from my father, now I think about it. But I simplified everything.

Parra:

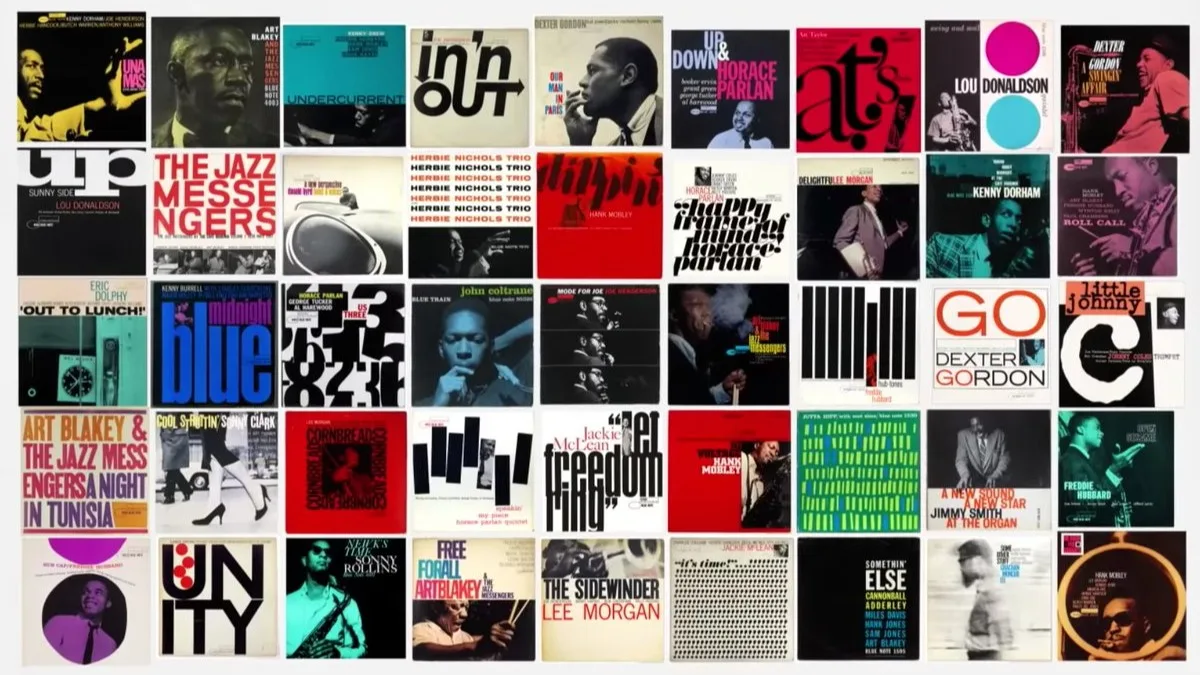

I think that’s because of the old record covers. At one point I was really into making beats and buying old records. Those jazz covers, what was that label called again? Blue Note! I really loved that it was duotone with one added color. I really liked that simplicity. To me, it’s just really conspicuous, clear, unambiguous language.

Parra:

I think I drew my first bird’s neck around 2003. That was for Rednose Distrikt, for Aardvarck and Steven de Peven. And that’s because they said do whatever you want. They were such a fun crowd...

Parra:

Yes, absolutely. They let me draw really freely and it all took off from there. Before that I was kind of in the hip-hop world, that was pretty rigid. If there was any pink included they were like, eh... If you get my drift.

Parra:

Yes, that happens when you’re an outsider who settles in Amsterdam. It was all very creative. And I was also lucky that I could do stuff abroad and not get immediately trashed here because I think that back then, much less now, I would have taken that really badly.

Parra:

I really have to produce canvasses and that’s really intense because for me it’s the most important thing. I don’t actually know why. I should attach just as much value to a T-shirt, I guess. But so much depends on it. People view my paintings differently than T-shirts or posters or other things I do. If I were a director, my paintings would be my feature films and the rest of what I do is a bunch of weird, short art films or even commercials or something like that.

Parra:

That’s even more intense. Only I get a lot of help with that, fortunately. It’s teamwork, which I almost never do. You work alone on a canvas.

Parra:

It was pretty challenging. I always used to go to it the first few years, then I skipped a few years and last time I went again and I was like, man, this is really fucking huge.

I thought about all the organizers and all the visitors and that’s when I thought about the idea of the rabbit, because I’d already made a small version of it once but it was terrible because I’d been in a hurry. That was for a group exhibition, a little pink rabbit called the anxiety rabbit. And then I thought, this is exactly the feeling I’m getting at the festival too.

Parra:

Yes, exactly. It’s a self-portrait, but it’s also a portrait of people who are always complaining about festivals.

Parra:

It’s black. Which I think is really daring, and it’s going to be really shiny.

Parra:

No, it’s really just black because all my larger sculptures are always black.

Parra:

I don’t know. Maybe because you don’t see what it is straight away. I think you could spend a long time looking at it. If it would be really red, it would be annoying. I don’t want to disrupt nature too much.

Parra:

Kind of, and it makes sense in multiple situations because that’s how I behave. That’s how I approach everything, actually. I stand on the sidelines. I know everyone, I participate to some extent and I observe and I comment.

Parra:

I’m not in a hurry.

Parra:

Not any more, no. But, it’s kind of, I’m there but I’m also not there. I don’t want to miss anything, I guess. I saw a stupid meme the other day, I can’t remember the exact words, but it was something like – I don’t want to go to the party, but I do want to be on the guest list. The guest list doesn’t bother me now. I don’t go anywhere any more. But I want to be on the Appelsap list if possible. Plus one.

Parra:

Sometimes I look at my work now and think I’m doing too much serious stuff. But hey, you can’t have it all. I guess these are just phases. Something silly is bound to come along soon. Something stupid will show up again. That’s what I think.

Parra:

To keep this up, that would be amazing. I’m not really looking to advance a whole lot further.

Parra:

No, I’m afraid that’s not a goal you can work to accomplish.

Parra:

Yes. Other people will decide that for you. All you can do is continue doing your thing and hoping that someone will pick it up. In that respect I’ve already been able to do so many things, so that’s super cool.

Parra:

Yes, trial and error. It sounds stupid, like who would do that? 14, 15 years old and then spending four hours jumping down a flight of ten stairs.

Parra:

Right, you don’t give up quickly. Or rather, I’m not easily satisfied. That’s also important. It’s like when you’re skating, you might land but your hands touch the ground, that’s a fuck-up. Try again.