Like many kids of the ‘80s, Motswana-Canadian artist Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum grew up on sci-fi novels and high fantasy movies like The NeverEnding Story, Legend and The Dark Crystal. But unlike most, this early influence has developed into a fascination with bending time. Alix-Rose Cowie meets the painter who happily puts women in Victorian dress in the same painting as a boxy BMW.

Images courtesy of Tiwani Contemporary.

Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum’s paintings contain conflicting references pinned to various points in history. “To me it’s really important that there’s this confusion of time when you look at the work,” she says. “I want it to be uncertain whether you’re looking into some deep past or some faraway future.” This desire is further fuelled by Pamela’s fascination with the unfolding discoveries in science and physics that help us better understand the shape and structure of the universe. “Those discoveries are sounding more and more sci-fi everyday,” she says. “When we’re looking at how time and space work, it’s becoming more and more fantastical.” She loves finding common threads between ancient cosmology and speculative science. “All of these ways of thinking seem to be after the same truth: What are we here for? What’s it all about?”

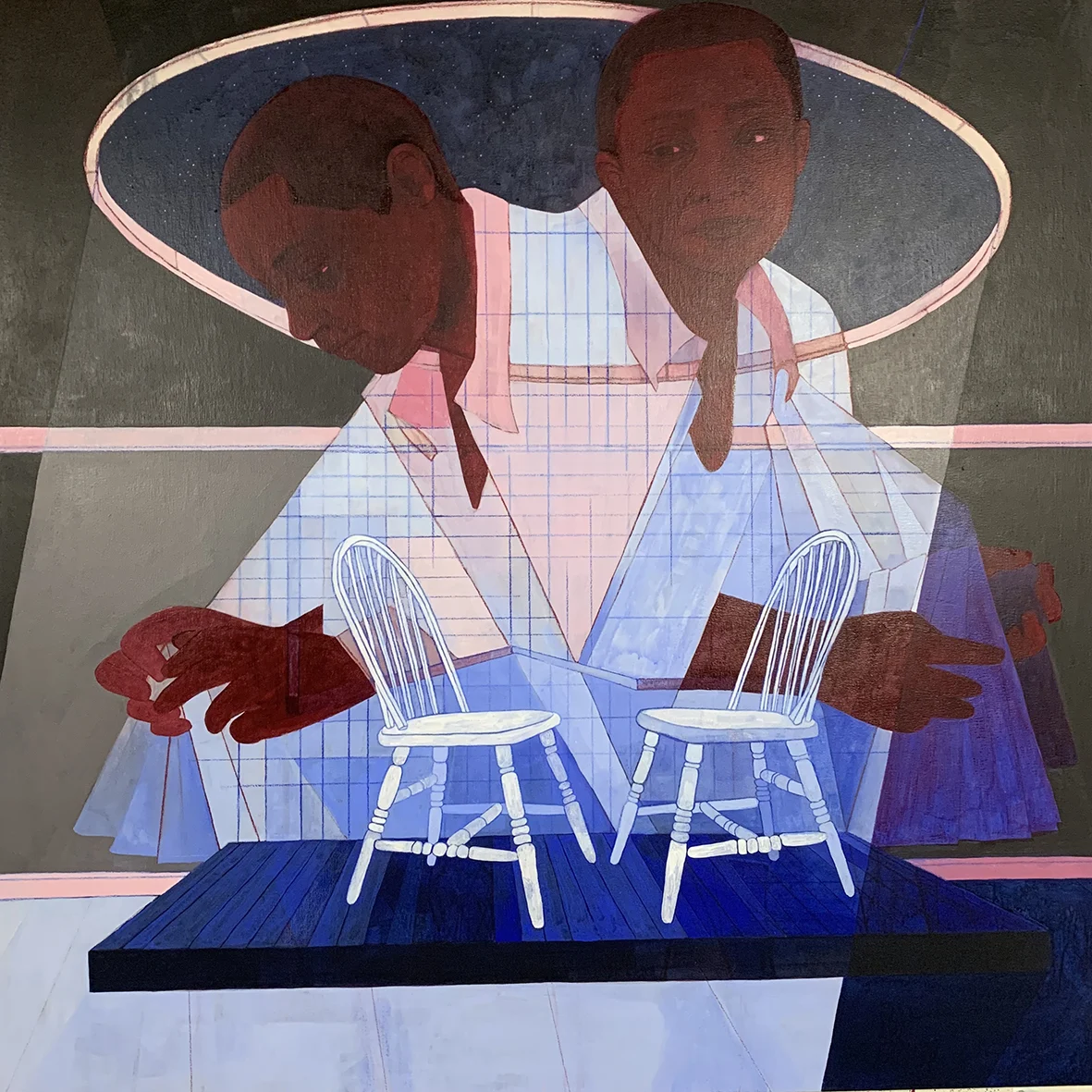

There’s a veil of mystery over Pamela’s paintings. The objects, subjects and landscapes in them are painted over each other in thin, see-through layers as if each is drawn onto transparent paper and placed in a pile. In a time where we consume images in blinks, her artworks make an appeal for prolonged staring. The longer you spend in front of one, the more secrets and clues are revealed. “They’re sort of like a scavenger hunt,” she says. “I like to reward people who take time to look.”

All of these ways of thinking seem to be after the same truth: What are we here for? What’s it all about?

Pamela sees all her work as one ongoing saga and uses art to write her own mythology. She thinks of her characters as ancestors or time-travelling parallel versions of herself. “I take great liberties to make believe in a lot of these works,” she says. She looks to classical moments in mythology: meeting the hero, the hero setting out on a quest, the hero being challenged or finding a travelling companion. The landscapes she incorporates into her paintings — a recurring, smoking volcano, a placid blue lake, or water bursting through a mighty dam wall — are meant to signal narrative moments for her figures; a certain tension or an inner conflict.

She thinks of these natural scenes as subconscious landscapes pieced together from her childhood memories growing up in different parts of Africa, Asia and North America as her parents travelled for work. She also borrows from European romantic painting. “They would make these beautiful sweeping, light-drenched vistas as a way of stirring the spirit, as a way of calling up this sublime experience of looking at the land,” she says. She considers it a political act to “steal” from European painters of the past.

Art history is also a source that Pamela dips into to find reference for the people in her work. She trawls the vast online archives made available to the public by museums like The Met and The Smithsonian. Digging through the collections, she looks out for photographic portraits from the early 19th Century through to the 1960s made in photo studios in West and Southern Africa. Many of these images were taken by African photographers and the subjects have agency in how they’re represented, which is significant within a history of photography on the continent dominated by colonial representations of African people.

There’s a certain formality to the occasion of being immortalized and the subjects are photographed dressed in their finest; either western suits or traditional kaftans or wrappers. They sit or stand alone or in groups against a variety of painted backdrops or drapery. Though Pamela references their poses or their dress in her work, she always changes their appearance or leaves their faces blank as a sign of respect. “They haven’t given me permission to use them in that way so I try to offer a sort of distance and also a way of making them anonymous,” she says.

Costume is an important device that Pamela uses to complicate time and place and she spends a lot of time thinking about what her characters are wearing. In The Incense Burner a woman’s billowing skirt seems to be made of mountains. She means for it to be ambiguous whether the woman has morphed with the landscape or whether it’s embroidery stitched into the garment. She references the decorative arts and uses her online resources to search for collections of old couture and handmade, stitched finery.

A lot of my mistakes and bad ideas are still sort of visible in the final work which is important to me as well

When online resources aren’t enough, Pamela visits thrift stores to hunt for vintage clothing. She dresses up in her finds, mixing time periods and clashing cultures, and then photographs herself in different poses to create rich reference material to draw from. She can take hours to get a pose just right. “Sometimes I’ll do these big photoshoots where I’ll set up an environment and invent a couple of characters and imagine what they’re wearing and what their interactive story may be,” she says.

Once she has a full bag of references, she pulls each out one by one and puzzles them together through the act of drawing and erasing and drawing and erasing to make something cohesive. “Most of what I do all day is just erase,” she says. “So many of the things that happen just happen in response to the struggle of making the thing.” Certain things remain and certain things get edited out but working initially with colored pencils, graphite and charcoal, it’s impossible to remove every trace which are still apparent through her watered-down acrylics. “A lot of my mistakes and bad ideas are still sort of visible in the final work which is important to me as well,” she says. The history of the artwork itself is part of its present.

The act of drawing and redrawing is also responsible for the many limbs of some of Pamela’s characters: legs in different positions appearing under robes, pairs of hands wrung together or dropped at their sides simultaneously. “Why I like to let those repetitions or erased lines show through is because it informs or suggests movement or many times at one moment,” she says. “So those many legs or many arms, on the one hand can be this physical mutation, this monstrous body but it can also suggest being able to see this body in motion in these discreet gestures.” They’re also a link to the incremental frames she threads together for her animated work.

Pamela’s early works are on paper, but its fragility meant that they would inevitably be framed behind glass. Whenever she saw one framed she’d be disappointed by the details lost in the reflections. She now draws and paints on sturdy wood panels that can hold their own but it’s taken years to figure out the surface. Between one and two inches deep, the wood panels protrude from the wall and confront the viewer when seen in an exhibition space imploring them to look longer.

When Pamela shares works or works-in-progress online she always does with one of two hashtags: #iamtellingyouaboutlove or #tellmeaboutlove. They reveal probably the biggest secret about her work: that it’s all about heartbreak. “I think a lot about love,” she says, “and I don’t mean love in the hearts and romance sense, but truly what moves us. The ways we are driven by love in its very many ways even though we know that often these pursuits are going to end up being tragic for us.” And this then is the key to the mystery: “The work really is about the beauty and pain of love and heartache.”