The story of Black cowboys goes back to the 19th Century, yet the vast majority of the old Western films failed to even acknowledge their existence. Obsessed with such films as a child, this is an omission Ghanaian painter Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe noticed from a young age. He tells writer Ferren Gipson how his striking portraits of Black cowboys are influenced by both the Black riders of the past and the present, and intend to inspire and educate the generations of the future.

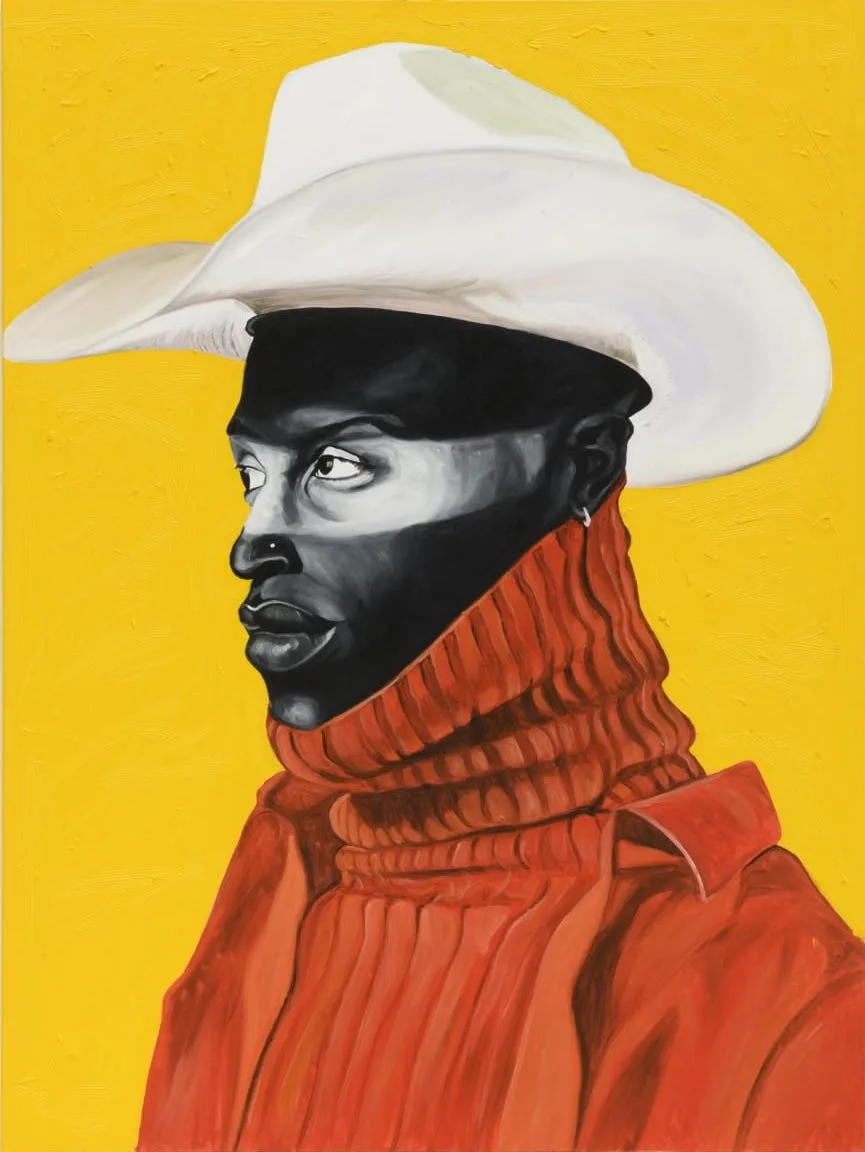

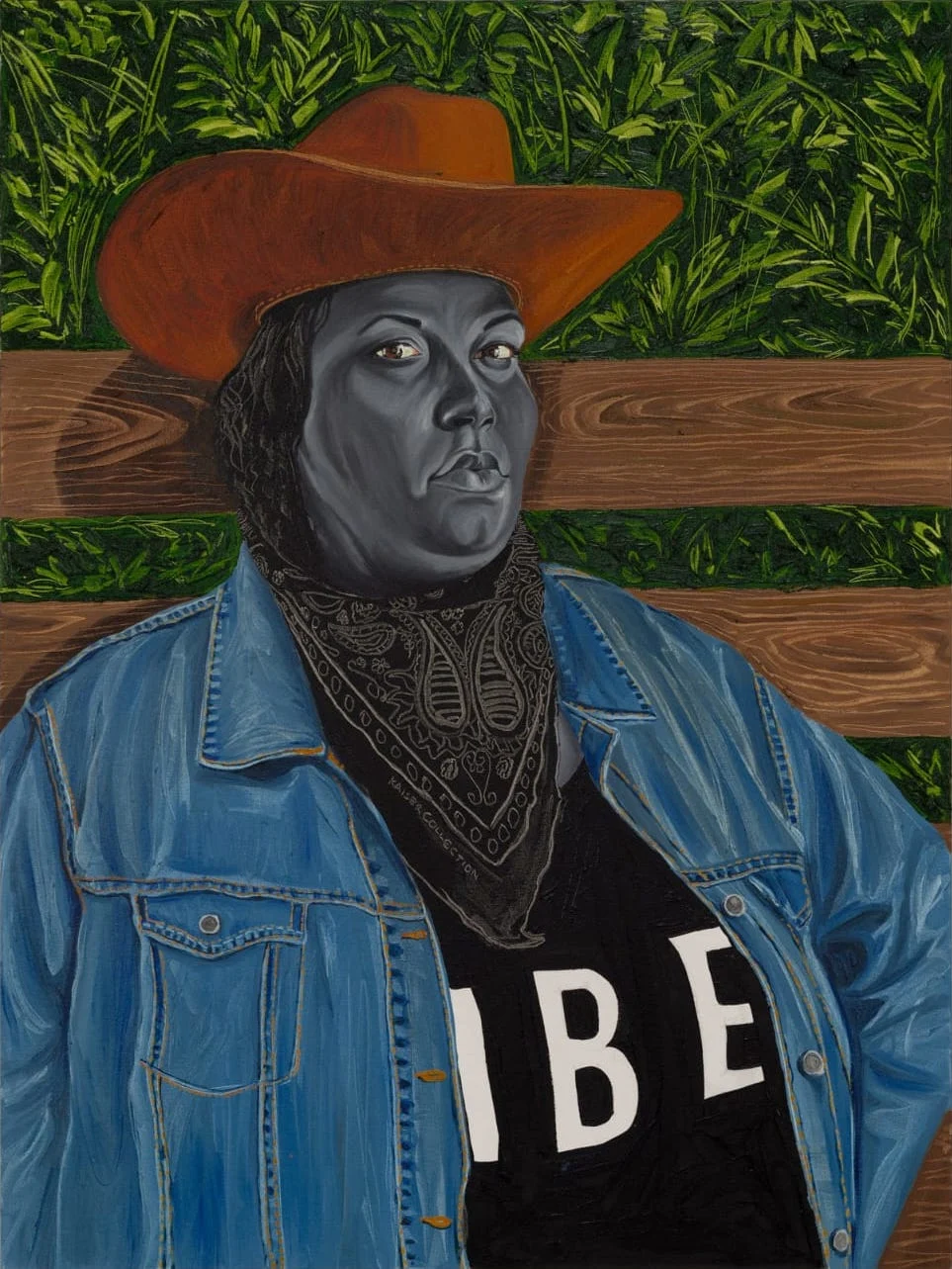

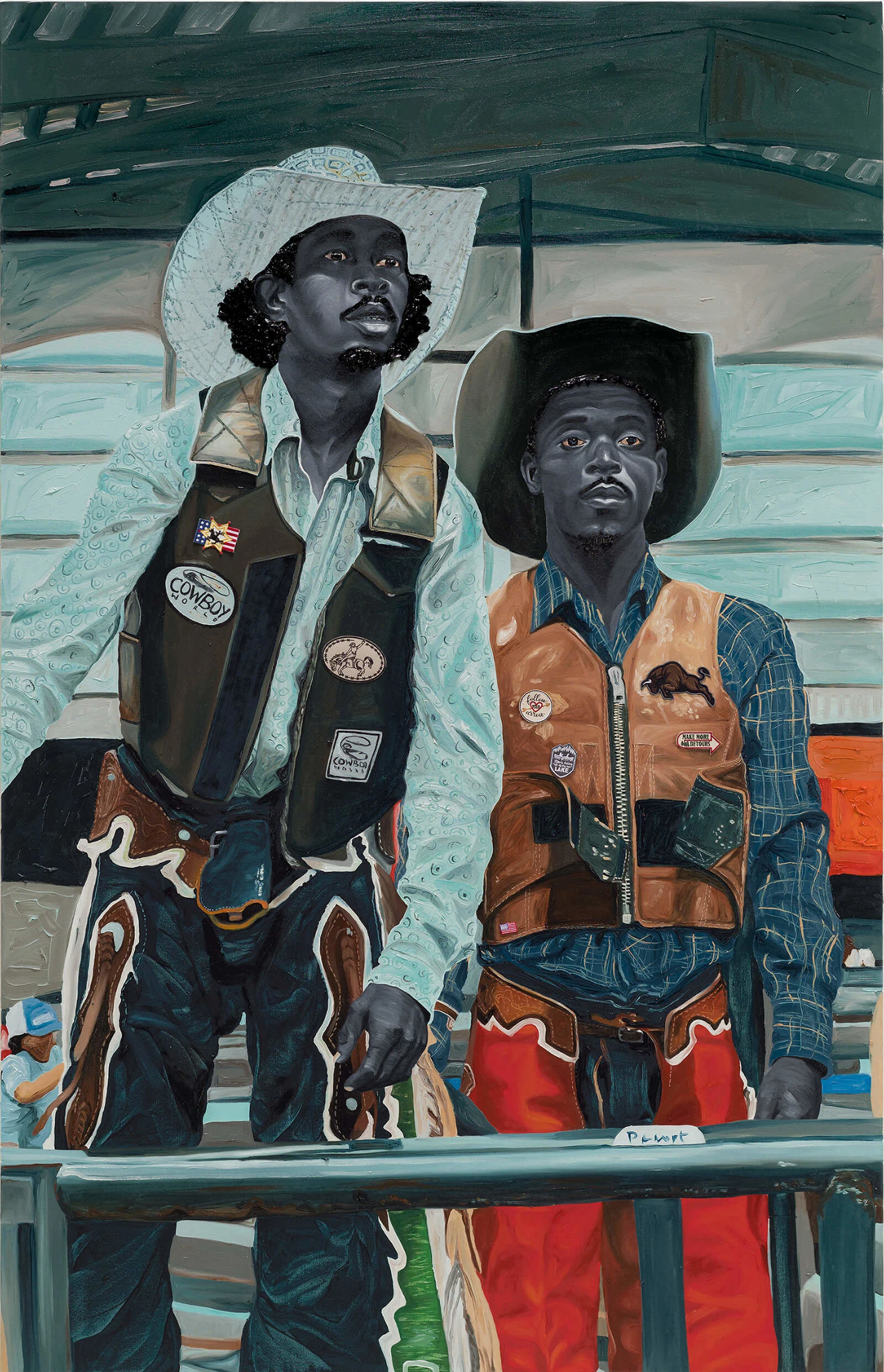

Viewers of Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe’s paintings are immediately met with striking visual contrasts, where bright, textured backgrounds meet smooth, grayscale figures. His ongoing series “Black Rodeo” depicts vibrant portraits of Black cowboys—a cultural combination that many may have never seen, despite a long history of Black people working that role since the days of the Old West. Each of these components connect back to the artist’s longstanding fascination with film and media, which began during his childhood in Ghana.

“I grew up watching a lot of westerns. We were all about the action movies and Hollywood,” says Quaicoe from his studio in Portland. “I grew up loving that and fantasizing about all this cowboy culture, their boots, how they speak.”

These images played in his mind for many years before coming to fruition in his current series, but long before he could produce these works, Quaicoe had to discover his interest in art. He attributes this development to the magic of movies as well—this time in the form of the giant film posters he encountered at the front of theaters. After learning that it was artists who created these images, he set out on a journey to learn how to draw by looking to other forms of media. “I started finding newspapers, prints, and magazines, just to recreate portraits,” he says.

Much of his work consists of intimate portraits. Their forms are naturalistic, but their monochromatic black and grey skin—sometimes overlaid with swirling white lines—clashes with reality. This aesthetic choice is as much a reference to Quaicoe’s love of old black and white photography as it is a way for him to process his experiences of how different societies engage with Blackness and cultural identity.

“It connects to talking about the color of our skin and the role it plays in where we live, or where we find ourselves in the world,” he says. “Where I come from, we are all Black. We don't wake up in the morning and think about our skin color. But [in the US], every focus is how you look. And it’s so funny to me because once I got here, [it’s like] I was no longer African. I was African-American because when people see me it's the color Black that comes to mind before they get to know where I truly come from.”

While watching news of the protests taking place in LA following the murder of George Floyd in 2020, Quaicoe noticed a group of Black horseback riders known as the Compton Cowboys among the crowds. The collective is composed of friends who have been riding together since childhood and who came to the sport through a programme aimed at redirecting inner-city kids away from crime. Quaicoe was amazed by the revelation that Black cowboys exist, and the scene brought memories of watching old western movies bubbling to the surface. He was soon immersed in a quest to discover other Black riders and to learn as much as possible about their history.

“Watching all of those movies, I never saw a main character that looked like me or shared my skin tone,” Quaicoe says. “So even as a teenager, these thoughts were running through my head, and I was wondering if somebody who looks like me could be the lead character.”

Many of his figures are inspired by photographs taken by his friend Ivan McClellan who captures portraits of Black riders around the country. A stunning example of this collaboration is “Portrait of Kortnee Solomon on Horseback” (2021), which shows the teenage girl astride a white horse in front of a leafy backdrop. Solomon is a fourth-generation cowgirl and has been quite the wunderkind, debuting at a rodeo at only five years old.

“Rodeo Boys” (2022) is based on another McClellan photograph and shows two bull riders standing on a chute (the enclosed area where riders mount bulls). In Quaicoe’s interpretation of the image, he adds patches to the figures’ vests, such as a man riding a bucking bronco and another of a charging bull, which provide more context to the scene and add a charming touch of Americana. The subtle inclusion of the US flag on one patch hints at how rodeo sports are associated with American culture, but it also invites the viewer to intersectionally reflect on how Black people enage with a broad array of traditions within that culture.

Creating the “Black Rodeo” series has enabled Quaicoe to tap into his longstanding interests in media and cowboy culture, but the work also has the potential to have a broader educational impact. He views his work as a document of what’s happening in the present, which connects us to history while also leaving a legacy for the future. While the story of Black cowboys extends back to the 19th century, Quaicoe says that he’s focused the representing the present in his work:

“I always say that when I go to museums and I see the old paintings, those artists spoke about their generation,” he says. “I believe there are a lot of people out there just like me that didn't know all this information about African-American cowboys or cowgirls,” he says. “I hope people can come to realize the same truth I got to find out; when I’ve shown these works, people have come up to me saying, ‘You know what? I didn’t know this really existed.’”

Looking ahead, Quaicoe still has much to explore in the cowboy series and is working towards gathering more information on the culture and history of Black riders, as well as continually building a body of work to support a larger exhibition of the works.

“We need to tell our own story,” he says on the importance of sharing Black histories. “It should be easy to access for everybody, so they can know about these people who played an important role in making this what it is today.”