With his synthy Lone Ranger aesthetic, Orville Peck is the masked musician who aims for sincerity. Leah Mandel finds out why he’s here to obliterate the tired preconceptions that have attached themselves to country music of the past.

Photography by Annie Forrest.

“I've been a fan of country music my whole life and there's no bigger weirdo than me,” Orville Peck tells me. The South African-born, Toronto-based breakout country musician is currently on the road, heading toward Montreal before going south for a US fall tour. We’re talking about the way country music is typically associated with conservative whiteness and Republican values, and why this yee haw moment we’re in is so full-fledged.

“There's something really liberating, exciting, and adventurous about country music and cowboy culture,” Peck continues. “There's this false stigma that it's not supposed to be for everyone. There's something really enticing about that.” The fact that a “gay black Reddit troll” can become a country sensation, for instance. That Kacey Musgraves can sing about queer love and pot and cop to writing “Space Cowboy” on acid. That it’s not just this macho right wing institution, and never has been. Commercial country radio isn’t the only place to hear country music. “I think people are just starting to realize that that culture is really for everybody. I'm happy because I've always loved country music and I've always loved the adventure of it. I'm happy that everyone else is finally discovering that as well. Everyone is welcome to it, everyone is a part of it, and anybody can be a country star. Anybody can be a cowboy.”

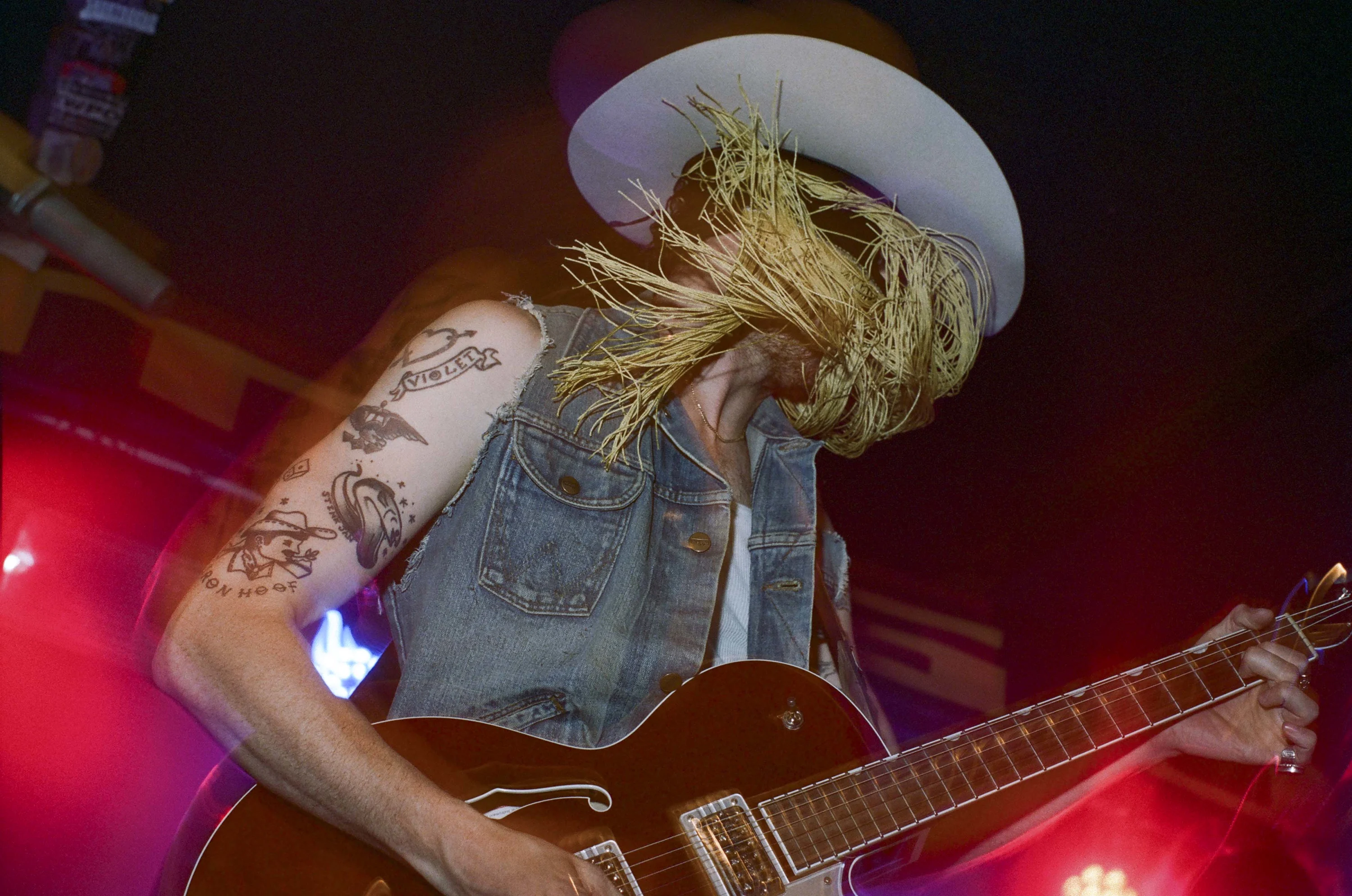

Orville Peck dropped his very first single in December of 2018, titled “Big Sky.” It’s a song that sounds smoky and ominous, like a cold desert at night. With Orville’s Roy Orbison-meets-Elvis voice singing about the aloof men he’s fallen in love with—the biker, the boxer, the jailor—interest was almost instantly piqued. Not to mention the nudie suits, and the red gallon hat, and—oh boy—the fringed leather masks. His clear-cut aesthetic and the way he subverts classic American imagery, something he and fellow citizen of the zeitgeist Lana Del Rey have in common, were enough to set him up for a cult following.

In January of this year came “Dead of Night,” a dusty, hitchhiking torch song with lines about dreamless nights, Carson City lights, strange canyon roads, and spending “Johnny’s cash” over languid steel guitar. His debut album, Pony, came out on Sub Pop in March. It’s filled with songs like the whistling, yee-hawing breakup track “Take You Back (The Iron Hoof Cattle Call),” and the echoey “Kansas (Remembers Me Now),” which, sounding at times like it’s coming from an old transistor radio, imagines a love between Perry Smith and Dick Hicock, the subjects of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. It’s all got a lot to do with love, with “the things we put ourselves through for the people we connect ourselves to,” Orville says. “Even knowing it's wrong, or knowing it's never gonna work, or it's never gonna be what you want it to be.”

I like things that aren’t afraid to go over the top but also have an honest quality to them.

There is internet chatter about Orville Peck’s true identity, but this is not something he himself acknowledges. “Well, that's my name,” he says when I ask if it is indeed Orville Peck I’m speaking with. Whether an alterego still exists or not is a mystery, but Orville Peck is not. He’s on the phone with me right now, loud and clear, and will, in our conversation, get a tad heated on the concept. It’s probably because nine out of ten headlines call Orville an enigmatic outlaw country star for our strange times. A synthy Lone Ranger. Masked and mysterious. But that’s “not the vibe,” he says.

“Mystery is something cultivated from me not being open with people. I do the complete opposite,” he explains. “It's actually like, participation. It's all out there. I'm not holding back or concealing anything. I write music that's extremely personal, and everything I sing about is literal life events I've been through.” It’s not vague, he says—it’s about cities, and people, and things he’s done. People he’s loved.

The masks, which he makes himself (his mom taught him how to sew when he was little), are just an extension of himself, an expression, like David Allan Coe’s mask and rhinestone suit. Or Johnny Cash’s all-black getup. Like Dolly Parton’s wigs! “I'm not setting out to be like, the Phantom of the Opera or something. I'm a country western star,” he says, “so I dress a certain way because that's how I want to present my art. But there are no secrets. I don't see what I do as any different from anybody in the canon of country music who had an aesthetic and put on a show, but also combined that with like, ultra sincerity. No one's saying , ‘Wow, look at that mysterious woman with the wig on her head.’ What's the mystery? I am an open book.”

In his music, he’s a Waylon Jennings type, an outlaw, a honky tonk hero. The vibe—a word Orville likes to use—is that wink of a line from “Ladies Love Outlaws,” the one that goes, “Ladies touch babies like a banker touches gold / And outlaws touch the ladies / Somewhere deep down in their soul” (only, make that lady one of the boys from Orville Peck’s songs). His sound, which draws from that golden era of ‘60s country music, is a moody, borderline goth take on the classic outlaw country of Jennings and his contemporaries, George Jones, Willie Nelson, Merle Haggard, et al. He especially recalls Marty Robbins, who had a more cinematic style to his music. The Chris Isaak comparison isn’t far off, either—Orville’s songs wouldn’t be out of place on a David Lynch soundtrack at all. And he and his music ooze sex.

For Orville, what draws him to country music is the storytelling, the artistry of the songwriting, the prowess of the vocals, the strength of the visuals—in the music, and its pomp. The romanticism, the narrative, the drama. He particularly loves country’s golden age because, “it carries intrigue and over-the-top colorful craziness. But it also has a genuine, sweet, private, understated quality to it. I like things that aren't afraid to go over the top and be bold and in your face but also have a real honest quality to them. That's how I hope to write music.”

A line it seems Orville tends to give when speaking about his project is that a tale gets taller each time you tell it, because you want to tell a good story. “But it’s still your story,” he says. “Country is really special in that way: time and time again artists have shown that you can.” This idea, I think, has been misconstrued. It’s not a wall Orville aims to build between himself and the world, by telling stories, by wearing a mask, by going by a different name. He’s said it himself, he has nothing to hide. Drama and sincerity are not opposed. A little glitz and glam, some showmanship, that doesn’t get in the way of the truth. A novel, or a drag performance, isn’t any less genuine because it involves exaggeration. It’s a funny paradox—today’s pop country gatekeepers are obsessed with the idea of “authenticity,” while shutting out the kinds of artists that made country great to begin with. Artists who are bold, and true to themselves.

Country music, Orville says, has “a rich history of more than just white men singing about trucks.” His zingers are lethal. “That is an almost ignorant view of what country music is. It’s like assuming that pop music is just the Backstreet Boys. It's such an entry level mistake that people make.” He gets especially passionate here, talking about country music’s many layers. “Cowboy culture, first of all,” he tells me, “comes from South America and Mexico. Most of the music is influenced by so many cultures. Sadly, it's been stigmatized by white old rich record label owners who probably wanted to keep that stigma going because it's financially beneficial to them.”

Right now, there is a wealth of alternative country music. British country-soul star Yola, New York synth-country songwriter Dougie Poole, New Orleans country-folk musician Esther Rose, and Massachussetts queer country singer Sam Buck are just a handful of Orville Peck’s indie, mold-pushing contemporaries. But it’s not a new phenomenon. “That happens in country all the time,” he says. “Every decade there's artists that come around and everyone says ‘Is this country? What is country? Who gets to decide?’ These are questions that have been asked a billion times.”

I’m happy to blow people's minds by literally doing nothing... just being myself.

Because country music has always been the everyman’s music, and the music sung by society’s outsiders—“lovable losers, no account boozers, and honky tonk heroes”—it has this innate openness. It has an ease, a comfort, a welcoming quality. Who amongst us doesn’t soften at a little twang? It makes total sense that when Orville Peck, a gay man who says he “felt ostracized his whole life,” did not feel excluded by country music. “Hey, I'm sure it would have been really nice if I'd had someone that really was singing about my circumstances,” he says. “But it didn't really bother me that there wasn't, weirdly.” Country music, he notes, might be more inclusive even than metal or hardcore, both white male-dominated scenes he’s been involved with.

Of course, it’s not his agenda to be the queer country star, the one Kacey Musgraves wished for. His only agenda is to be sincere, he tells me, which is something he’s struggled with in the past, making other forms of music. “It's more of a personal vendetta than anything,” he says. “I'm happy to blow people's minds by literally”—he drops the ‘e’, for emphasis—“doing nothing. Just being myself.”

The cowboy aesthetic is seeping into all corners of culture. Gallon hats grace the pages of fashion magazines; indie rock musicians Mitski and Mac DeMarco both used the word “cowboy” in their most recent album titles; Mason Ramsey, the yodeling Walmart kid, went from viral content to full-blown child star (Orville compares him to Aaron Carter, or Shirley Temple, though I say the Twang EP is good). It’s almost as though “Old Town Road” was just a symptom of something larger. Orville, by the way, thinks Lil Nas X’s come-up is rad: “Does it sound like the country music being played on country radio? Absolutely. Is it weird that there's a trap beat country song? Not at all. Because it's like, 2020 or whatever the fuck year we're in and it completely makes sense. The most noteworthy thing about it is that a black gay kid who basically got himself noticed by being a Reddit troll and a Barb, beat every single record and was on the cover of TIME, and that's fucking cool and I'm really happy for him and I like his song.”

Ultimately, Orville Peck is really just happy to extend the invitation to his love of country music, to help eliminate the illusion of snobbery and the money-fueled exclusiveness of it all. “When people come to my shows, or meet me, or just listen to the record, I'm really happy that in a very short amount of time people's misconceptions or preconceptions about what I'm doing, or what I'm trying to do, seem to go away. Because everyone connects with the music, or with the story I'm telling. I feel really confident that a lot of people have had their preconceptions destroyed.”