“Not where I expected, but...OK,” reads the fictitious review of The Standard, a trendy hotel usually located in Manhattan. “At first I was annoyed. I was like, where the EF is the standard? Then we ordered an uber and it took us OVER 24 HOURS to get to the ACTUAL standard .”

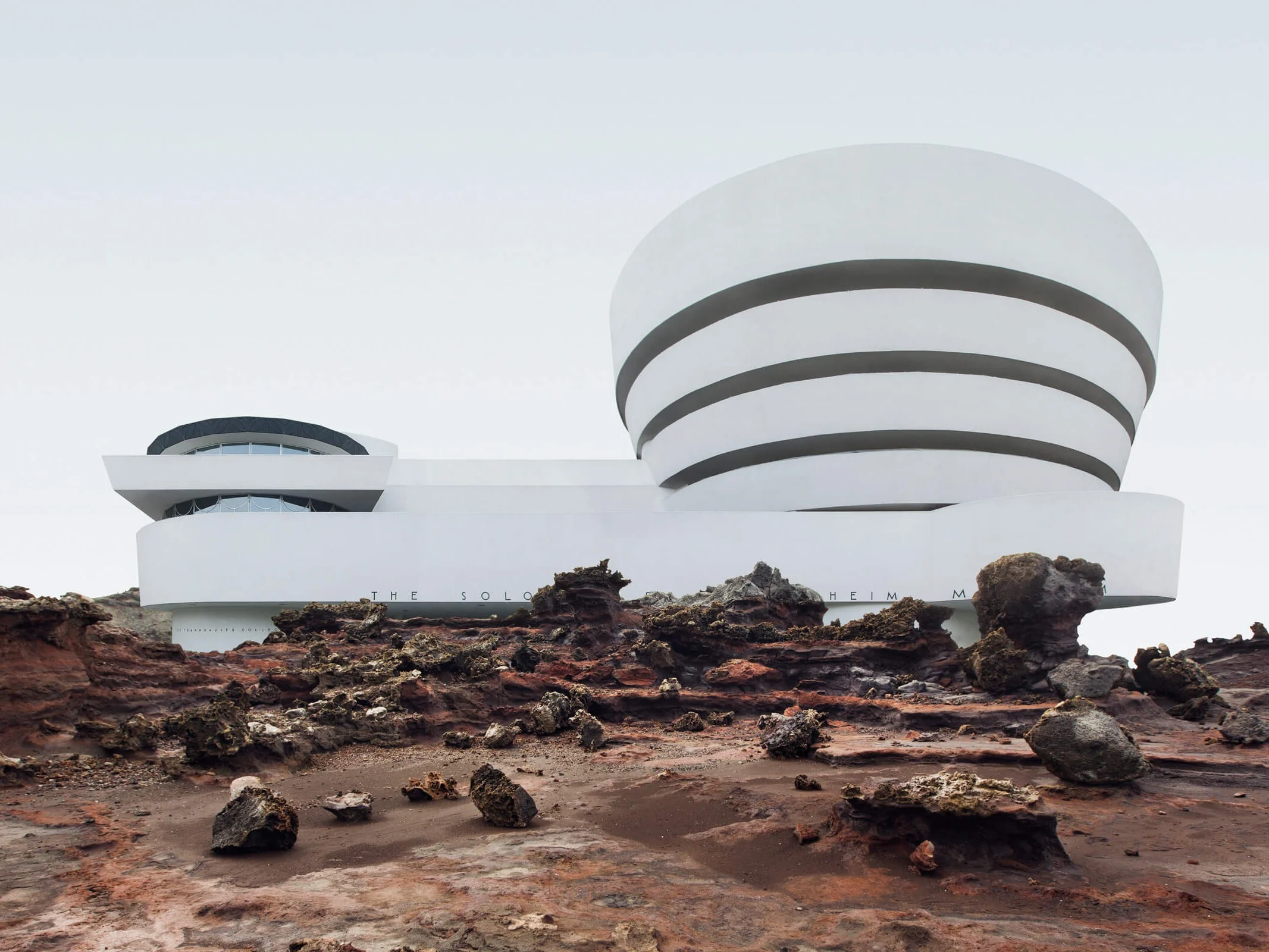

Understandable, since the New York hotel has been transported from the trendy Meatpacking District to a bleak, rocky terrain for Anton Repponen’s intriguing project Misplaced.

In the project, it’s not just The Standard that’s been removed from New York and into unknown territory. The Whitney museum is roaming the desolate plains of Mozambique while the Chrysler Building has gone off for some “me time away from all the oohing and ahhing.”

Anton designed these deceptive images to see what New York’s iconic buildings would look without “all the garbage that people surround them with.” Alongside them, on the brilliantly designed website, you can read stories on how these buildings came to be misplaced.

“A lot of people know what the Guggenheim Museum looks like,” he says, “but the moment you see the building out of context it’s very strange.” Placing them in a new environment without typical city distractions like tourists, traffic signs and flashing neon lights, Anton presents each building as if fresh from its blueprint. “I was restoring it back to the architectural plan,” he says.

The project started as an experiment. After visiting an exhibition by Markus Brunetti , who’d spent ten years photographing churches to capture their grandeur without the interruptions of daily life, Anton couldn’t understand how each image was so pristine. “It was completely insane,” he says.

I would spend hours trying to straighten them up so there was no distortion in perspective.

In an effort to uncover Markus’ technique, Anton began reading all the interviews he could get his hands on, yet the artist revealed nothing. “So, I decided to dedicate the next couple of months of my life trying to figure out exactly how he did it — or at least get as close as possible.

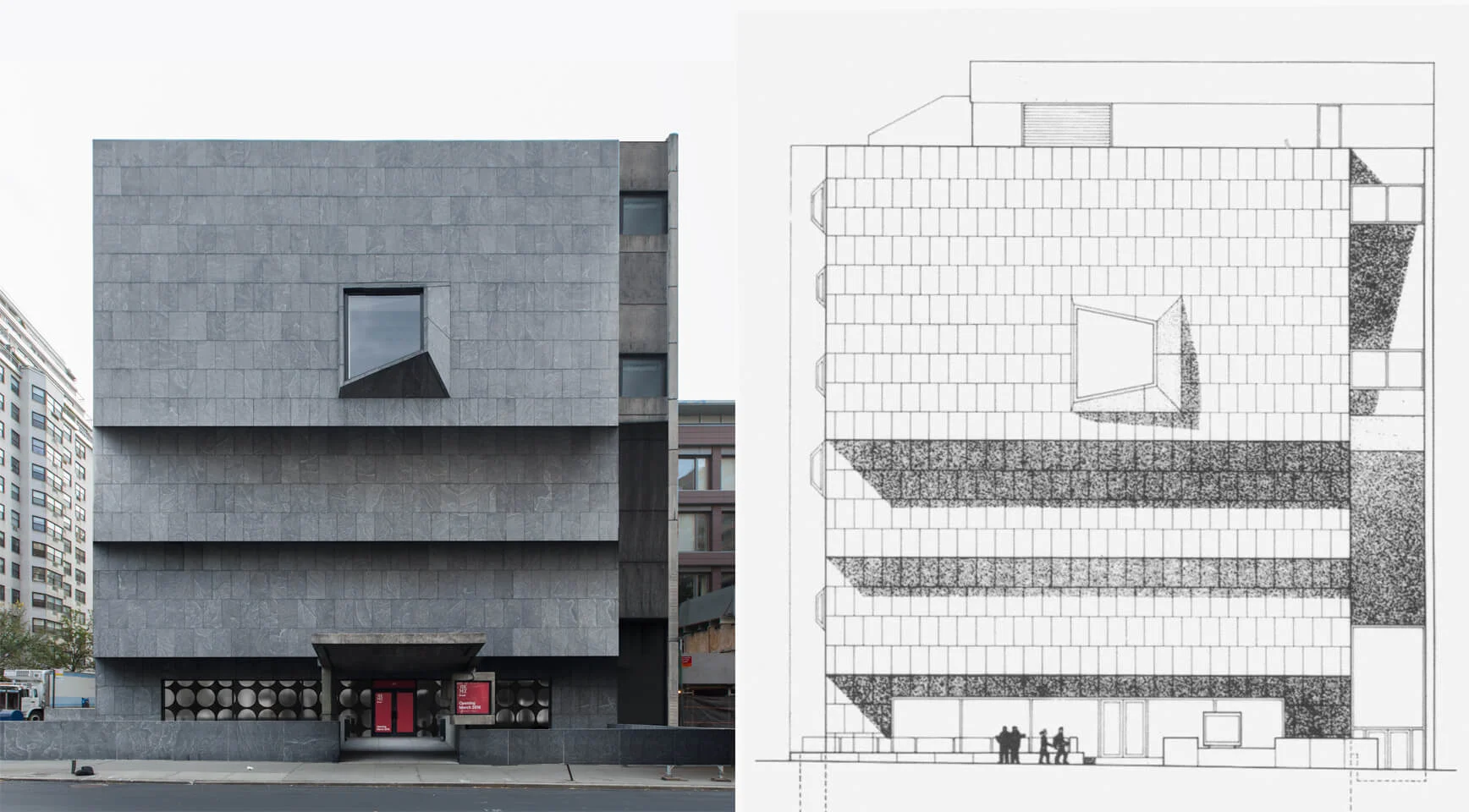

“I would cycle around New York taking pictures of buildings then spend hours trying to straighten them up so there was no distortion in perspective, as well as clean up the facade — removing things like the pharmacy next door or the bookshop on the first floor.”

Photographing buildings may seem quite straightforward, however on a scale like New York — where skyscrapers tower along every street — it felt like an almost impossible challenge.

“If the building is taller than five or six stories a standard wide angle lens wouldn’t work,” Anton says. “The taller the building, the more distortion I’d get on the upper floors.” In this case he’d usually upgrade to a 50mm or 70mm lens , but using such a lens would mean not being able to fit a full building in the frame, as the narrow, crowded streets of New York don’t allow for enough distance. So he broke most buildings down into smaller chunks, capturing the upper and lower quadrants separately.

The problem with breaking things into pieces comes with gluing them back together. “Putting a building in the desert is a one hour job. Preparing the building to be placed in the desert is a five day job,” Anton says.

Putting a building in the desert is a one hour job. Preparing the building to be placed in the desert is a five day job.

For this he used a tool called PT Gui, which enabled him to identify specific pixels in an image to then match them up with the same pixels in another image. “I’d have to do this a thousand times, basically mapping every single pixel so the software knew how to merge the images together.”

The meticulous nature of this process took its toll. “On month four, I had maybe nine buildings and I was like what the fuck am I doing here? It doesn’t make any sense. Nobody needs it, it’s a waste of my life,” he says.

“But at the same time it was snowing outside, so I was like, whatever, I’m going to keep going.” After correcting color and perspective, then cleaning, merging and cutting out the images, it was time to misplace them.

As a long time photographer, Anton used his own archive of more than 20,000 images of his travels around the world for the locations. “I would try the images with each building, almost like trying on clothes — let’s try this ocean, this desert, these cliffs, those rocks.” And although he used existing places he visited, the resulting images almost look like the iconic buildings are placed on a whole different planet.

But the work still wasn’t done. “I realized that having images alone wasn’t that interesting. So I thought it would be funny to write a little story explaining why the misplacing had happened — almost like a whodunnit or a parody of the building.”

Anton reached out to good friend and journalist, Jon Earle. “Basically my brief was write whatever you want as long as it’s edgy, as long as there’s some humor, or maybe it’s just a little bit insulting.”

The stories that accompany each misplaced building are all very different, from the Guggenheim’s board of directors sending migrant workers to “scour the earth for primitive lands that knew nothing of modern and contemporary art,” to the revelation that Frank Gehry’s IAC Building is inspired by none other than a Monty Python song.

And although all 11 texts are equally brilliant, Anton admits his favorite might be The Standard. “It’s a hotel here in Chelsea where a drink costs at least $30 and we misplaced it among the rocks of Hawaii. Jon wrote a story as if it was a Yelp! review — “Coco got a gross skin rash and refused to leave her room… (PS: DON’T DRINK THE TAP WATER!)”

“That really makes the project, I think it’s perfect.”

Words by Robyn Collinge.