In this day and age you don’t often hear about the little people that take on the big corporations and win. However, this did happen to the Native Americans in North Dakota who were opposed to the planned oil pipeline that would cross their land. Mico Toledo, a Brazilian documentary photographer, was impressed by the ambitions of this peaceful but strong-willed group, and so he flew out there to document them. The result, his series Faces of Standing Rock, portrays the protesters of the pipeline.

“This particular story of the Standing Rock Reservation – a classic David vs. Goliath theme – somehow reverberated with me,” Mico explains. It is a tale of a big corporation overshadowing a minority with a very slim chance to succeed. Whatever side you are on, it is an interesting situation in which 200 tribes joined forces to reach a shared goal – to stop the North Dakota Access Pipeline.

Not everyone agreed with the beauty of this coming together of people. “The local media were quick to dismiss the Native Americans as troublemakers, but their own labelling of ‘water protectors’ sounded much deeper and appealing to me,” he says.

On top of that, Mico strongly believes that the arts have an critical role in supporting minority groups.

There is an utter importance in art tackling stories of inequality because the big mainstream media usually do not do so.

“It’s the duty of non-commercial writers, artists, photographers and documentary makers to tell those stories from the fringe that otherwise wouldn’t be heard across the world,” Mico continues.

So instead of painting a picture of resistance and protest, he photographed the people while they gathered, prayed and volunteered in the camps. “I wanted to tell the little stories behind the front line and capture the beauty and strength in these individual characters.”

The Native Americans were very welcoming to Mico – they offered him food and a place to stay and were ok with him taking their picture. “The photography was always something that came in the end of the conversation. It was important to me to understand their stories, to be genuinely curious and respectful and I didn’t want to be perceived as a photography hunter,” he says.

It helped that he worked with medium format film (a Hasselblad 500cm). This way of shooting takes longer than usual, which resulted in Mico having to spend some time with his subjects. “It’s a process that is actually quite beneficial for the pictures because it allows people to relax and be their own self instead of posing for pictures.”

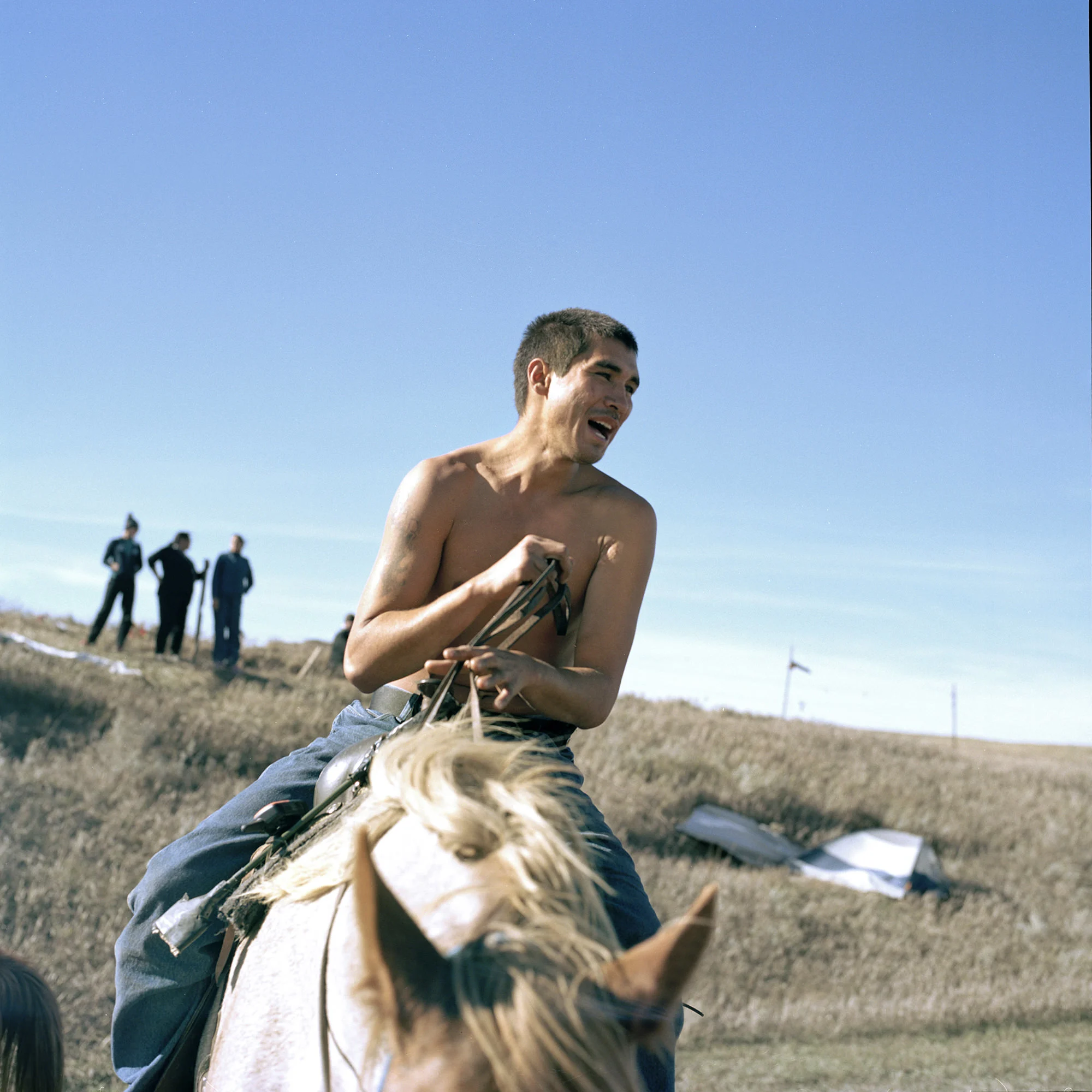

This rider’s white horse was everything he had to protect himself from tanks, heavy artillery, and anti-protest forces deployed by the North Dakotan police and local sheriff’s departments.

“This rider’s white horse was everything he had to protect himself from tanks, heavy artillery, and anti-protest forces deployed by the North Dakotan police and local sheriff’s departments. The incredible display of force against peaceful protesters, families and native Americans stroke me as unnecessary.”

Mico loves documentary photography because it allows him to step out of his comfort zone. “I always say that a camera is just an excuse to experience a life outside our bubble and see the world through a different lens.”

Shooting this series, Mico was most impressed by the tribes’ refreshingly different view on the world. “The idea of labels, races and nations is kind of irrelevant to them. Natives taught me that we’re all sons and daughters of the same earth and we don’t really own anything, we merely take care of it for the next generation,” he says.

“It may sound like some hippie mumbo-jumbo but I think this is the way the Natives preserved their way of life, land and nature for thousands of years, and we have a lot to learn from them if we want to keep living in this place for many years to come.”