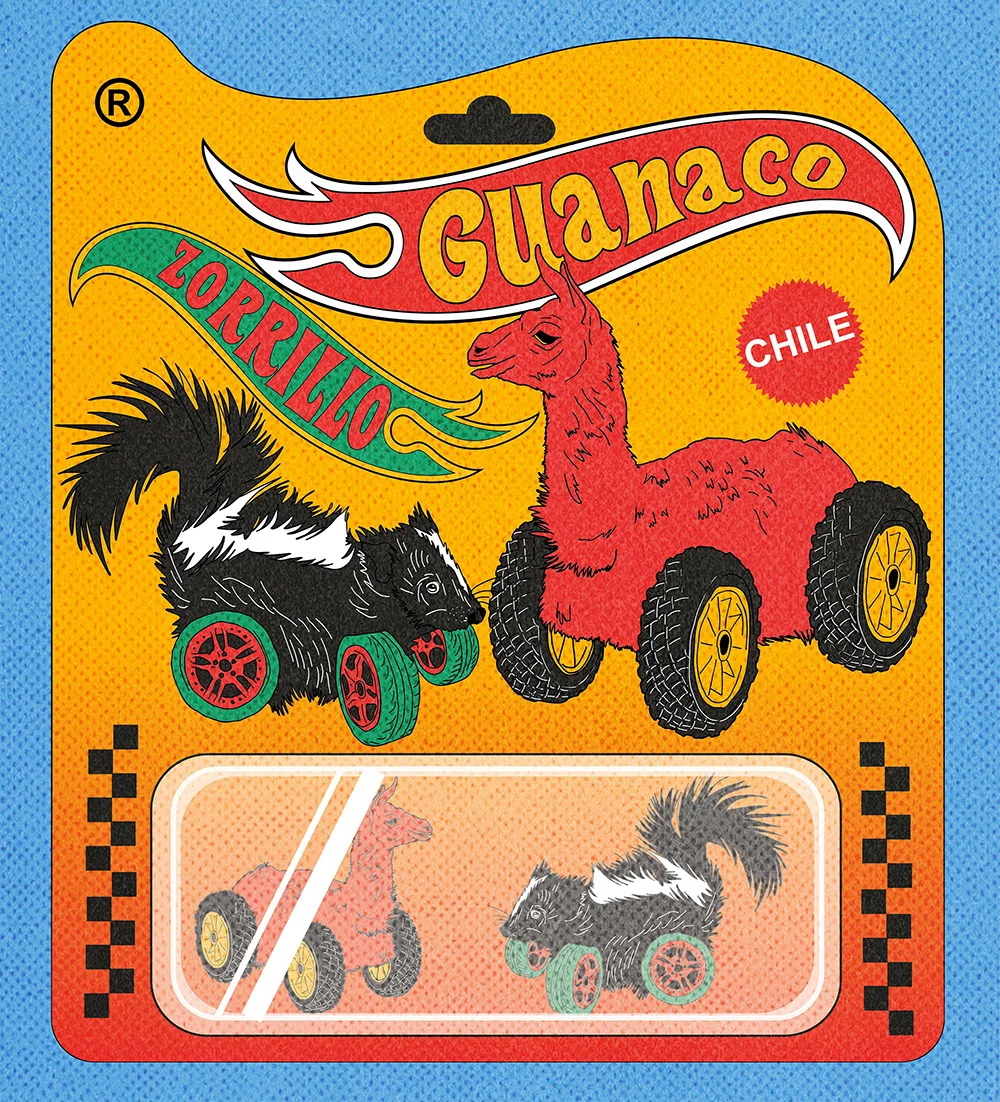

María Jesús Contreras never considered herself an illustrator until one day somebody said, “I like your illustrations.” They might have been referring to her use of colour so saturated that it triggers the childhood memory of pressing a felt tip pen hard into a piece of paper as a kid until the ink bleeds right through, or her irregular linework that gives raw and urgent energy to her drawings. Or they could’ve been a fan of her sardonic sense of humor. Writer Alix-Rose Cowie finds out.

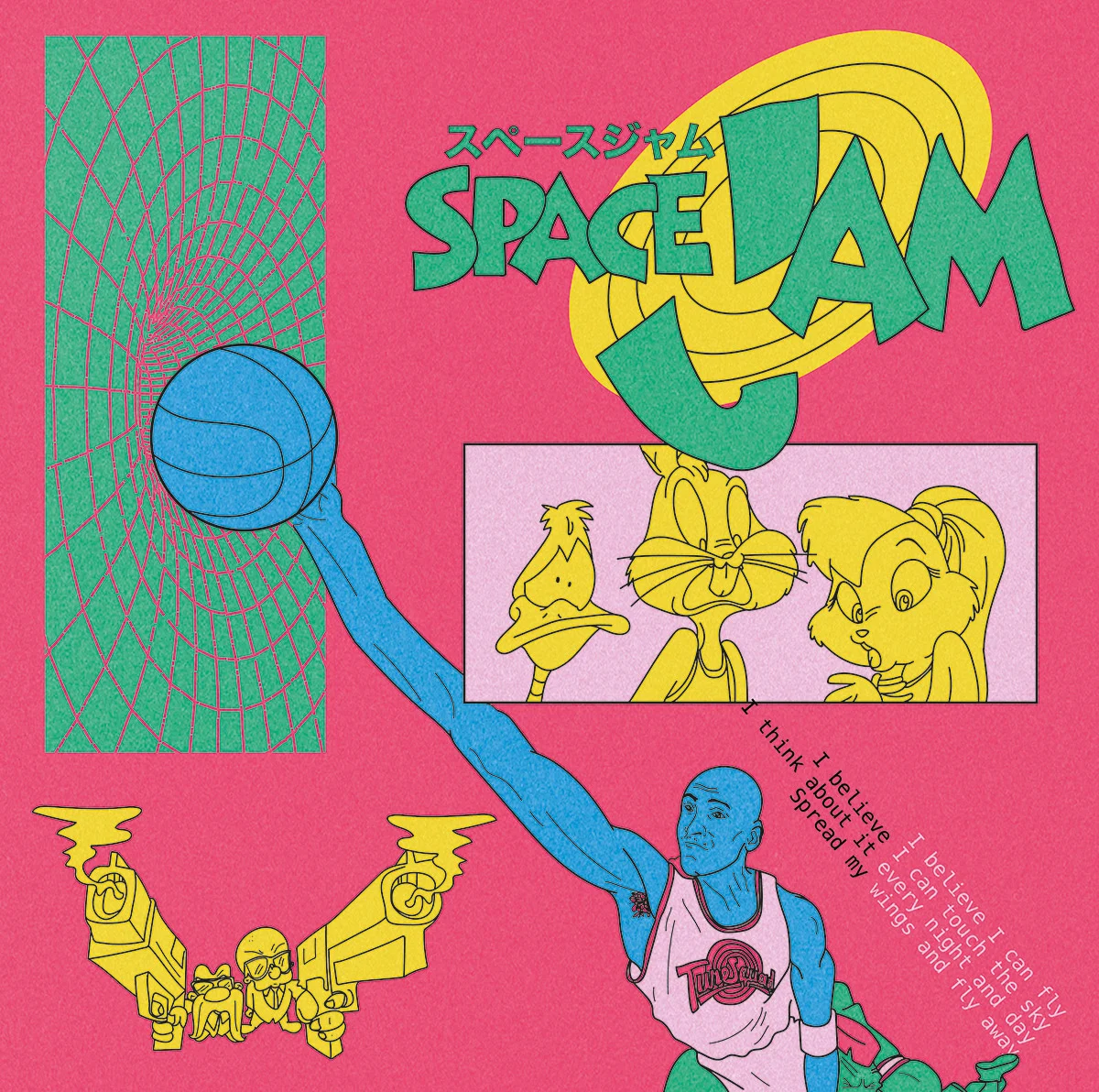

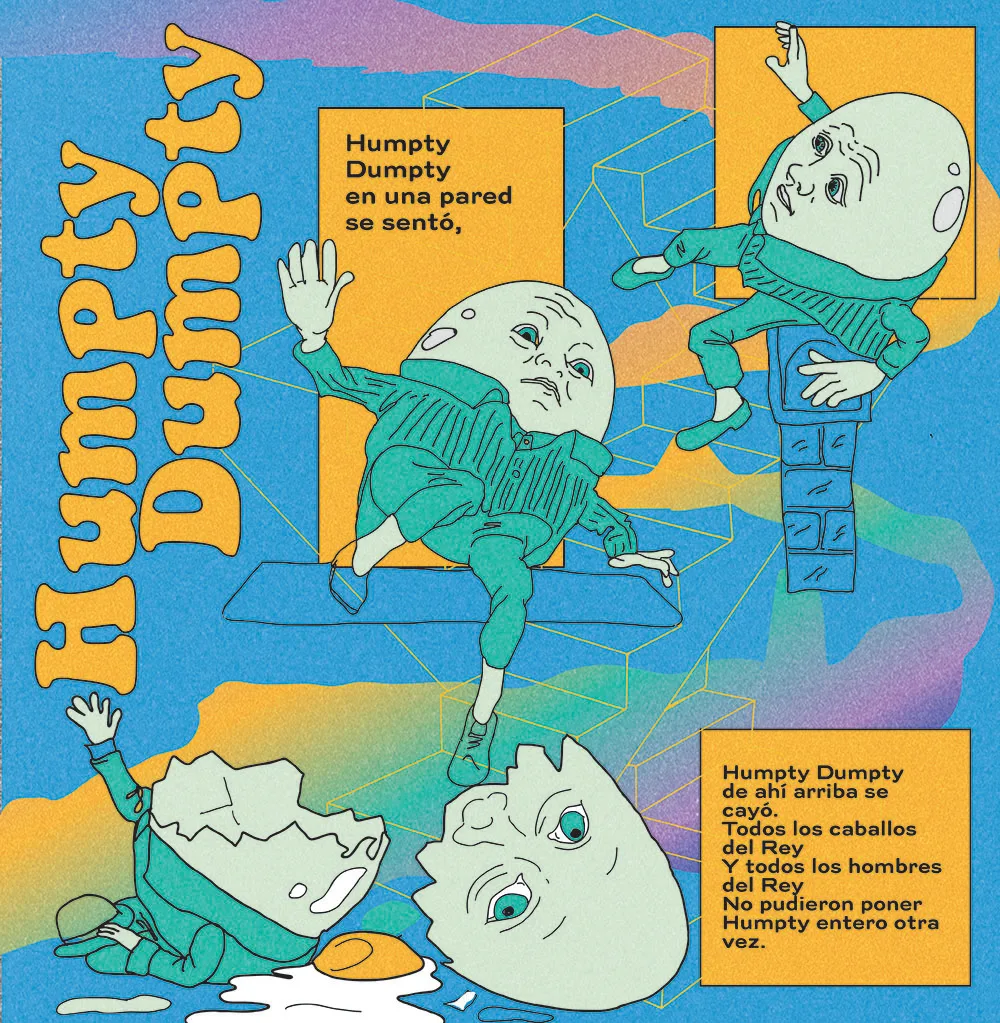

María had a rainy childhood growing up in the countryside of a small city called Temuco in southern Chile. Perhaps that’s why so many of the artworks she makes now based in Santiago reference movies from the ‘90s: Space Jam, The Parent Trap, Matilda or the original Jumanji. She does this as a kind of catharsis. Through remembering and drawing childhood movies, she addresses past traumas. “My drawings have always been a way to externalise internal images that cause me fear, to visualize and to know them,” she says. “Then I transform them into a composition and add color so I can see them in perspective and they no longer only live inside me.”

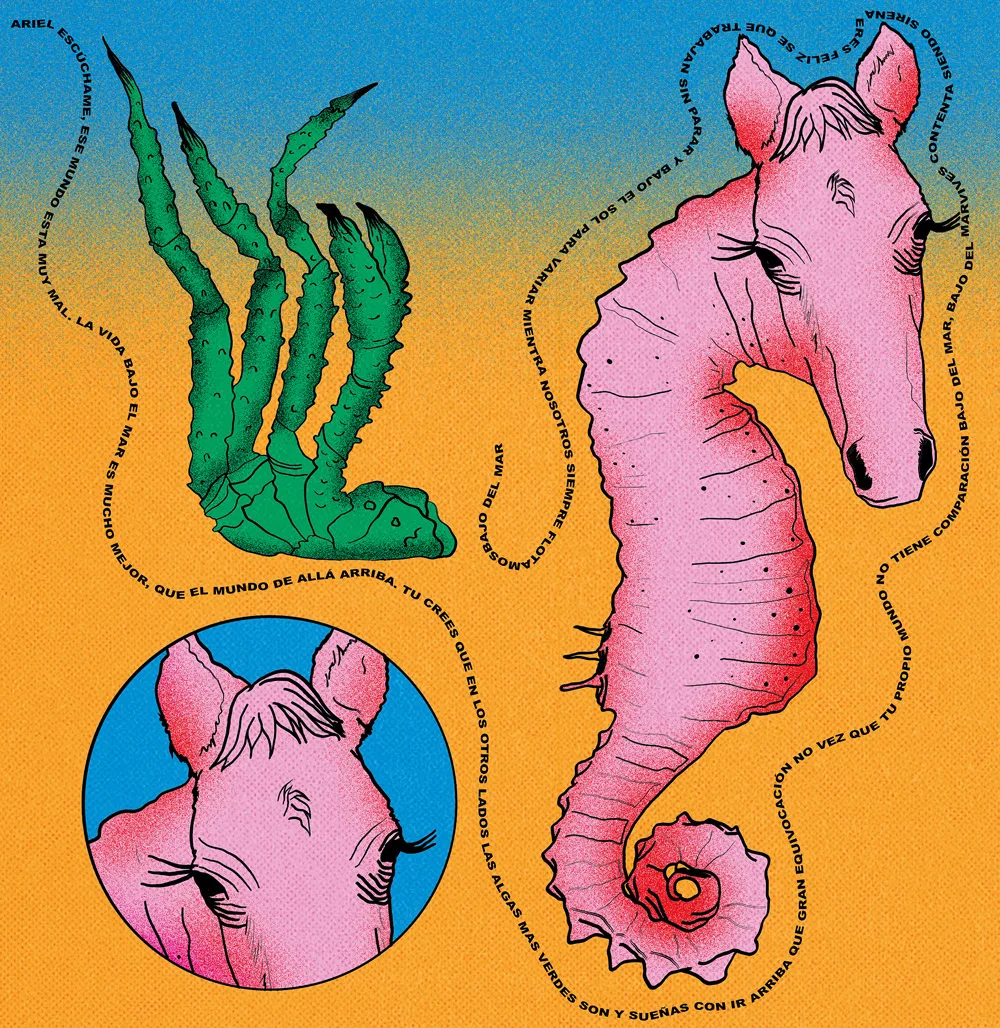

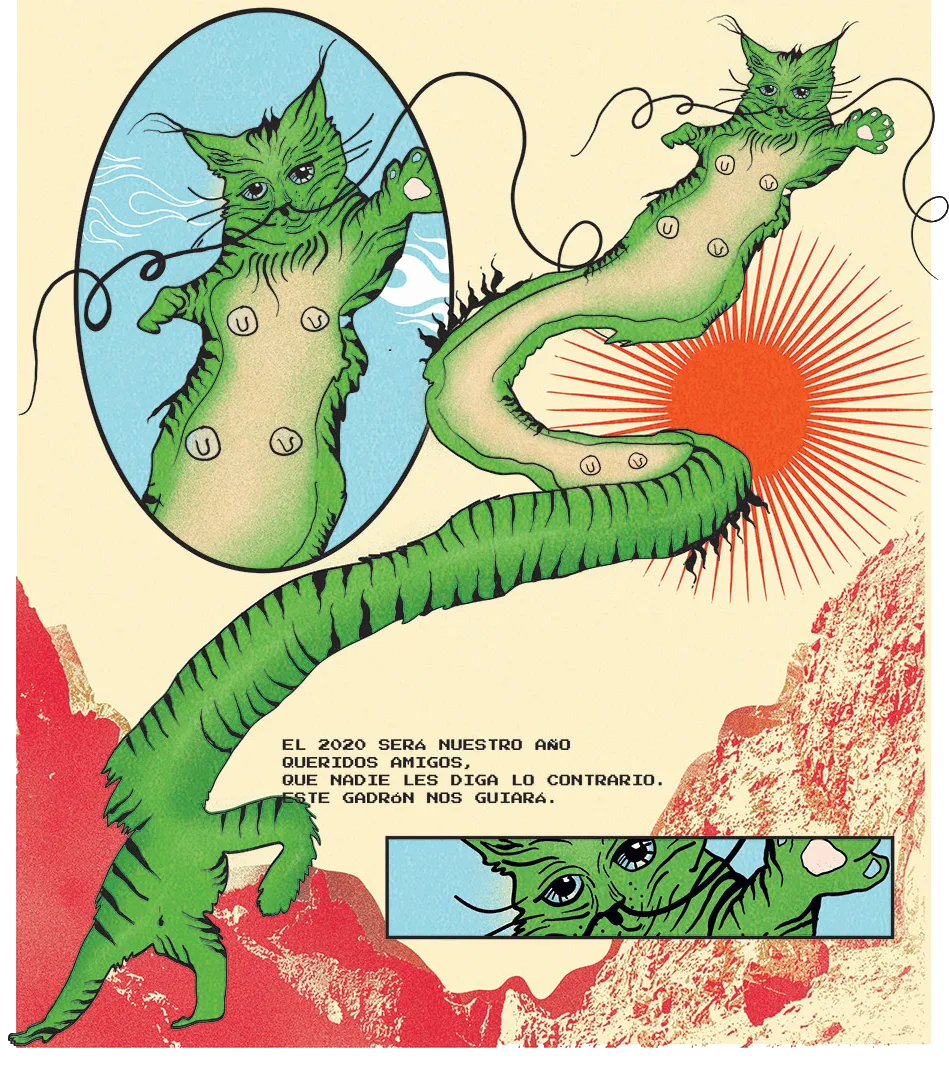

Or she might just have the theme song stuck in her head, as was the case with her seahorse drawing inspired by The Little Mermaid: “Darling it’s better, down where it’s wetter, take it from me.” As is her way to twist reality and make things a little darker, and a little more weird, the pink seahorse body has a real horse’s face. “It makes me laugh when we give ocean animals land names: hammerhead, swordfish, seahorse,” she says. “The Little Mermaid is also a product of the humanization of everything caused by the human ego.”

Artists have always used creative weapons to defend themselves and those they love.

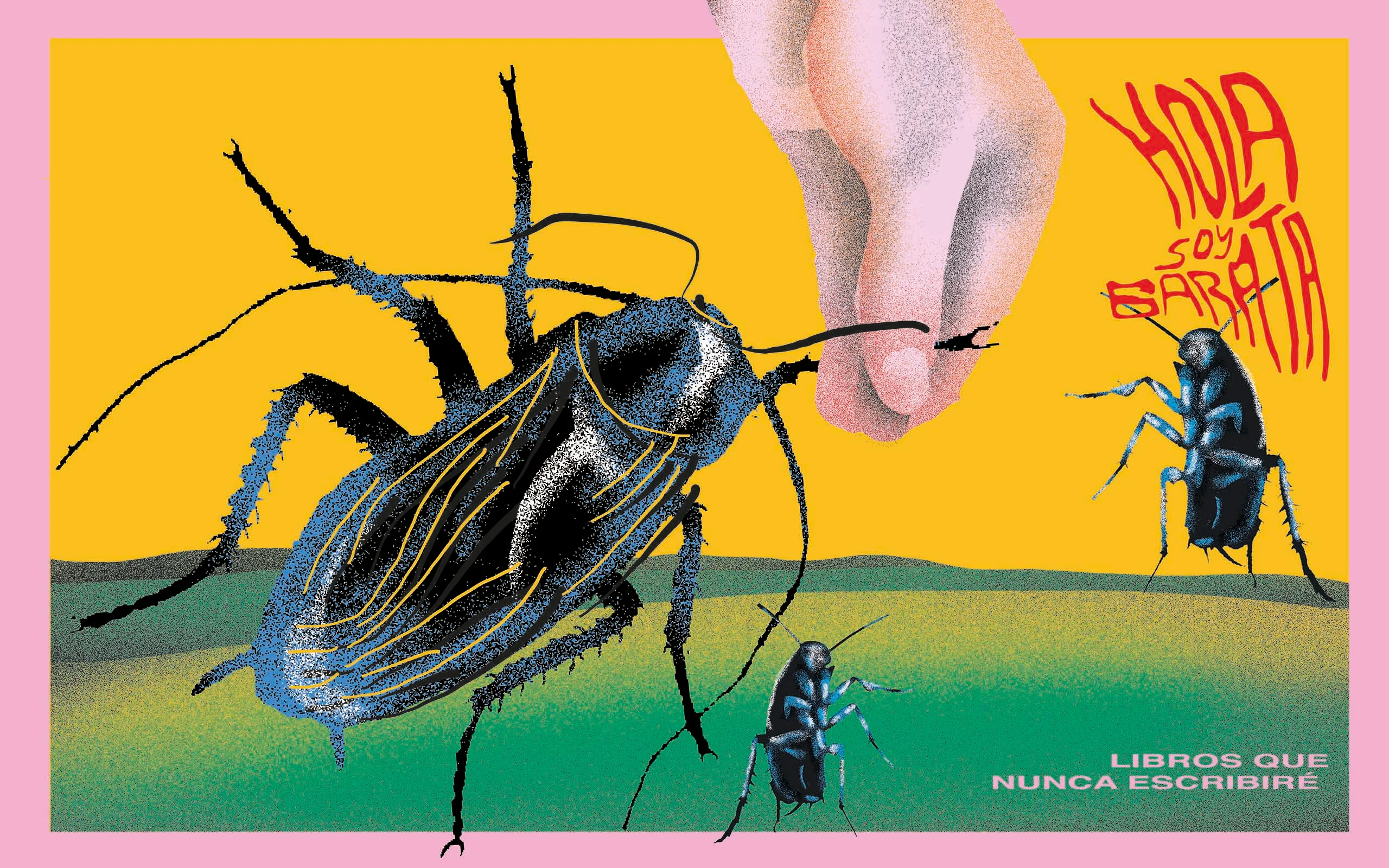

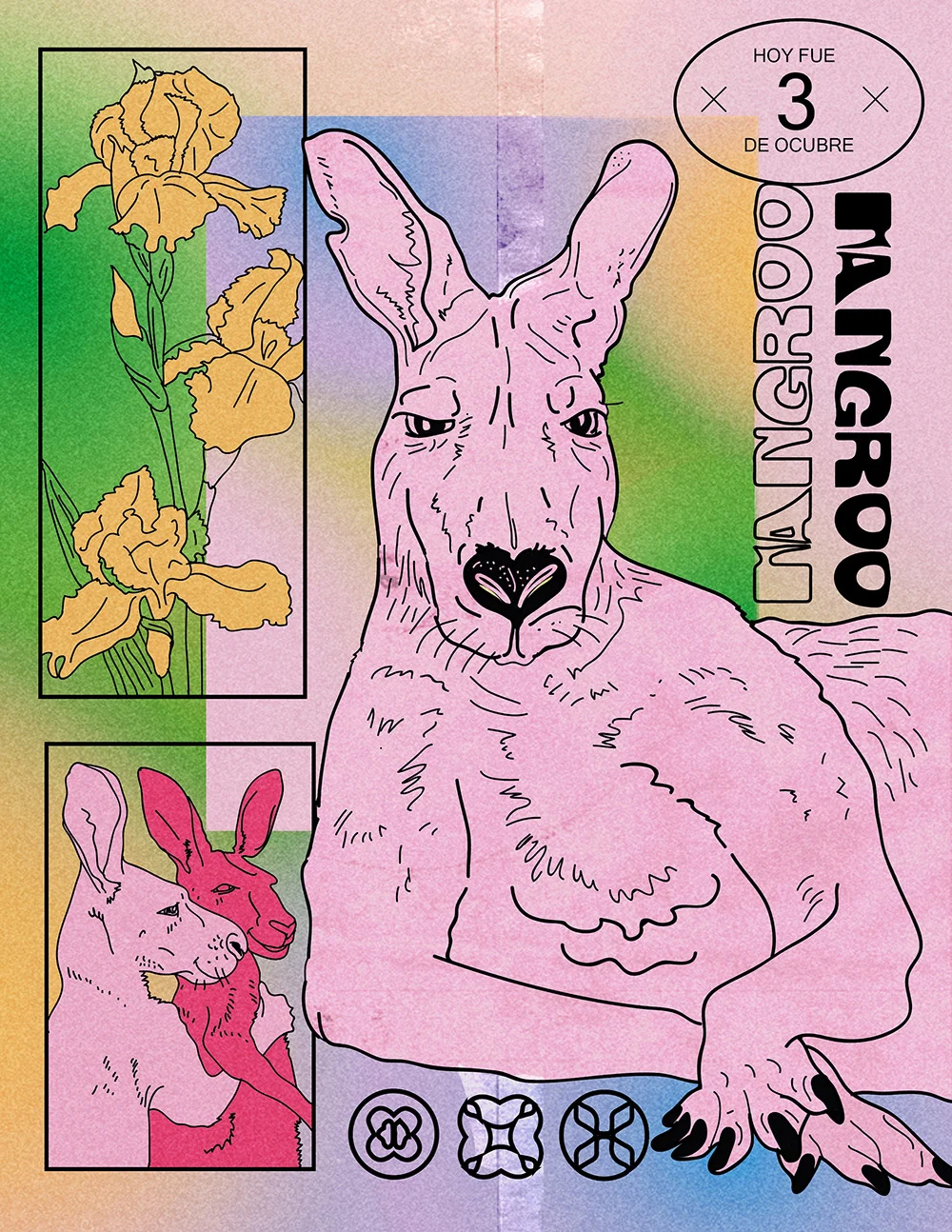

It’s a tactic María uses to create disconcerting images of objects with human or animal features. “I like creatures,” she says. “Whenever I walk down the street I imagine that objects have a face or a personality.” When her imagination really runs away with her she can sometimes feel like she’s in the MGMT music video for Kids, in which a crying baby is the only one who can see horrifying monsters as his mother carries him along the high street. María uses her pens to create her own monsters, “which are a bit more ridiculous and less frightening.” She tags these images on Instagram using #creepyart. “I’m trying to visit the darkest parts of my personality on a daily basis,” she says. “I never really thought that people would receive it so well. I suppose they must also connect with these parts of themselves.”

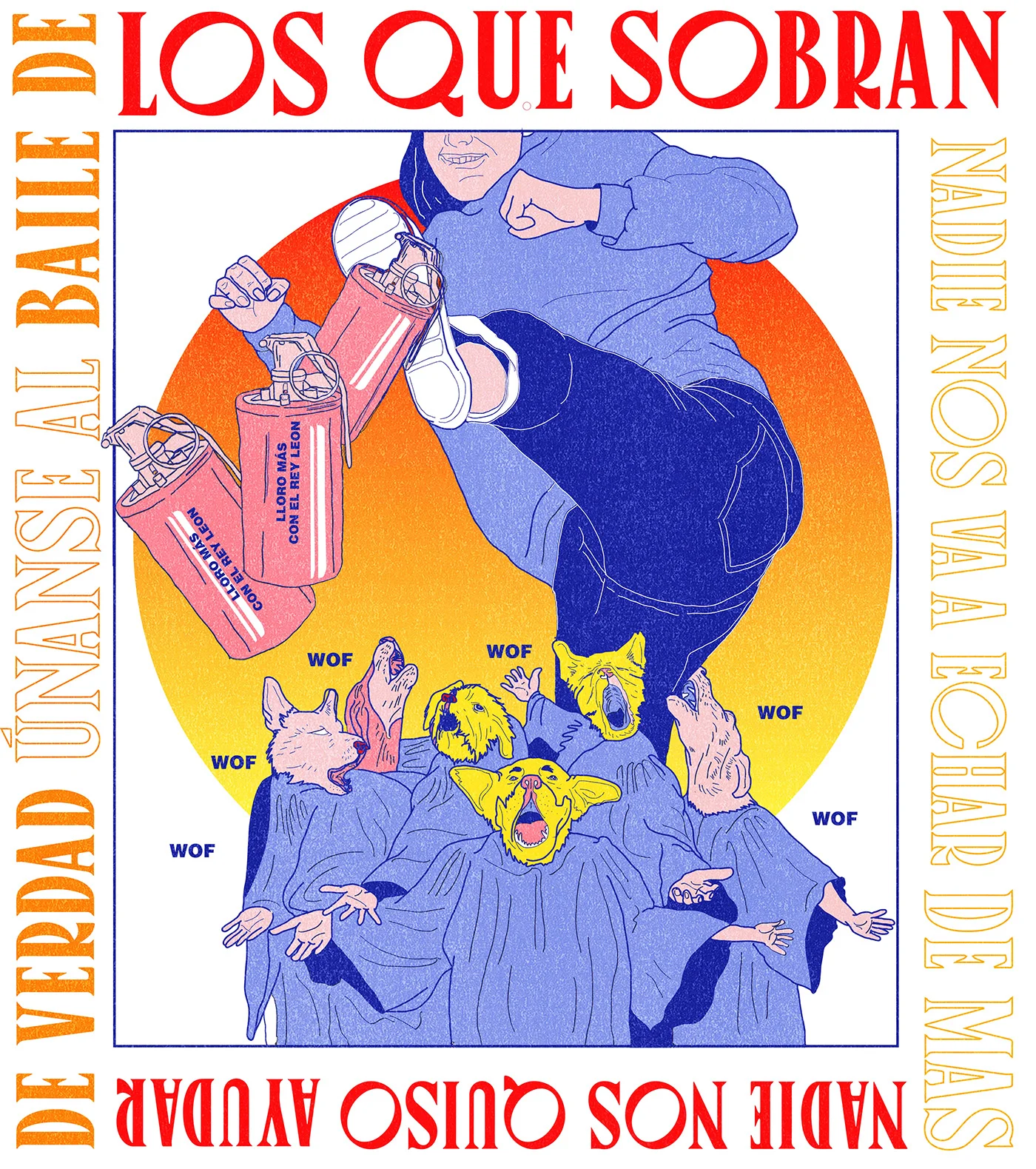

Recently María’s work has been inspired by voicing a response to more real threats. In October 2019 student-led demonstrations began in Santiago, sparked by an increase in metro fares. As the momentum grew, the protests evolved to become resistance to the high cost of living and inequality in the country. The protesters were met with tear gas and rubber bullets from the police. “I graduated from university recently,” María says, “and it is the first time that I’m faced with what families in my country experience day by day.” She was inspired to make artwork in support of the protesters. “It was spontaneous and from my feelings,” she says. “Artists, being quite sensitive beings, have used creative weapons to defend themselves and those they love.”

She’s since created a collection of artwork commenting on police brutality. One image shares information about the different eyewear protesters can wear to protect themselves from incoming police pellets. In another, a protestor fly kicks cans of tear gas as a choir of dogs sings a protest song from the military coup in the ‘80s that has become a street anthem once again. Another is a protester starter kit which says in Spanish; “It’s never too late to be a rebel.” In the list of illustrated items are a cooking pot and a spoon, used by many of the protestors to make noise in what often started out as peaceful demonstrations.

It’s not about being political, it's about being part of society.

“When life hurts, humor is a lifesaver,” she says. The risograph-like texture she adds to her images digitally lends itself beautifully to being printed on paper and she’s made high resolution versions of her protest art available on Behance for anybody to download and use in protests or share on social media. She initially makes the work to express herself but this way it allows others to express themselves too. “I don't think it's about being political,” she says, “it's about being part of society.”

“Everyone has their own struggles; political, social, emotional, existential,” she says. “The important thing is to deal in some creative way, to give birth to something beautiful that we all have inside us.”