Berlin-based, Japanese photographer Kyoko Takemura’s project “Born for Such a Time as This” features shots of questionably-painted figurines of Jesus Christ, Virgin Mary costumes and expensive vials of holy water, many of which were mass-produced in nations that are majority atheist. Allyssia Alleyne hears about how the project shows that, in today’s world, even the most sacred of things can be commercialised and profited from, and asks why, for want of a better phrase, “Jesus sells.”

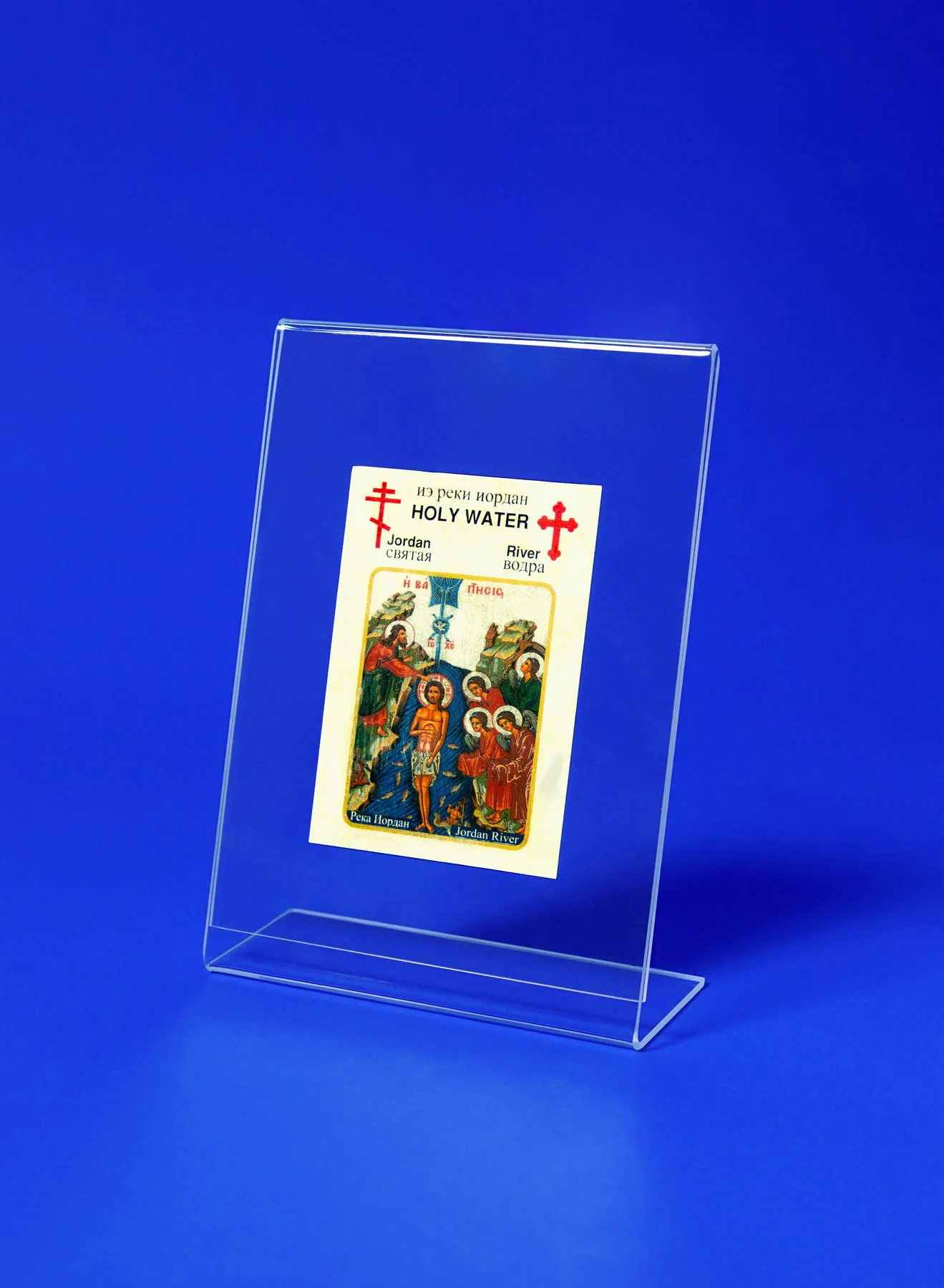

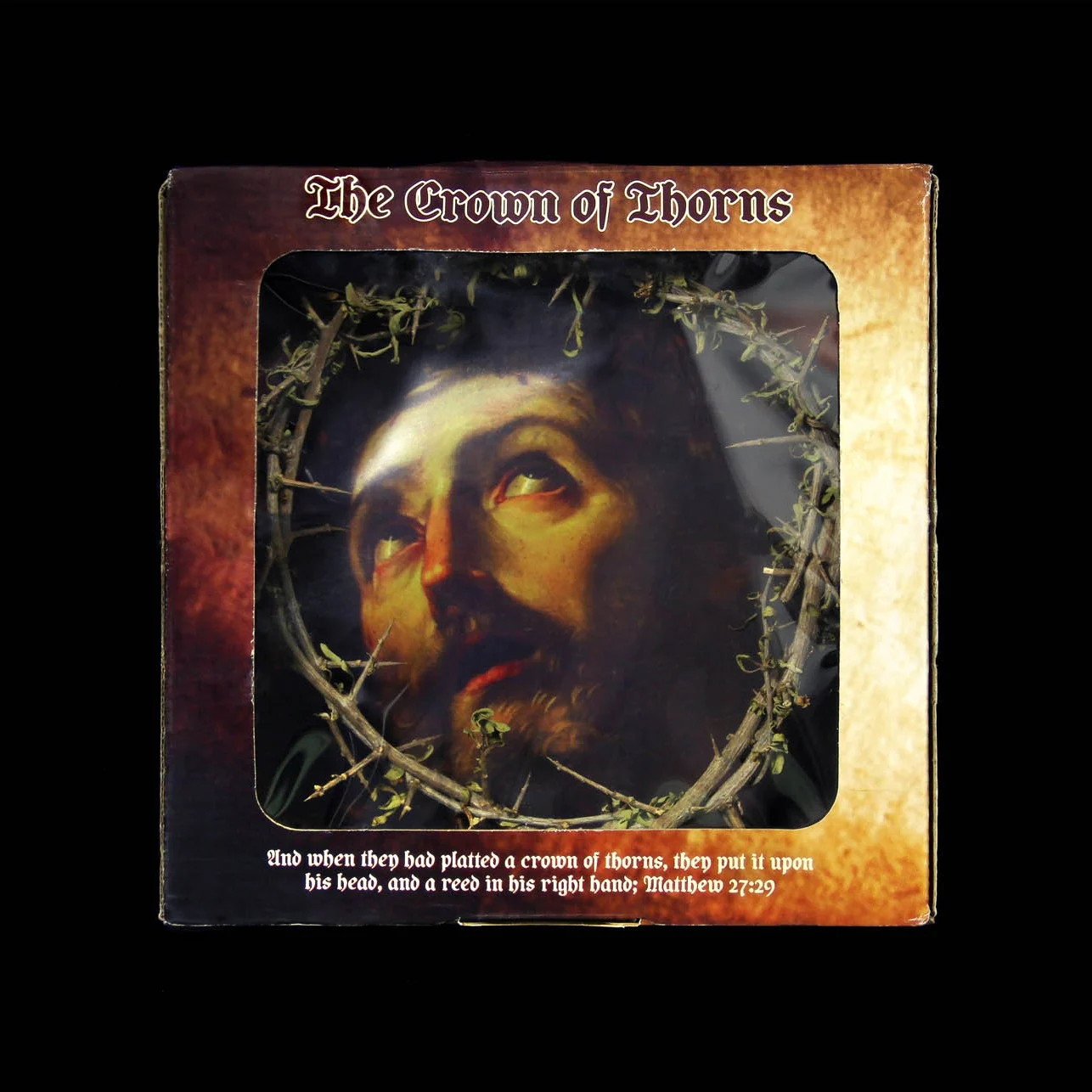

Kyoko Takemura’s Amazon order history is something to behold. Among her purchases are vials of holy soil and oil, a crown of thorns, a Virgin Mary costume, a smiling Jesus plushie, a cube with a portrait of Jesus etched within it, and an impressive array of Virgin Mary figurines, with and without child. “The 3D crystal of Jesus is my favorite,” she says, pointing out the unusualness of his East Asian facial features. “I thought, ‘why not?’ Given he was a Middle Eastern Jew, he wasn’t a white guy like the prevailing image of him anyway.”

These objects are a sampling of the nearly 40 objects the Berlin-based conceptual artist shot for her 2023 series “Born for Such a Time as This.” Produced over six months, it highlights the glut of mass-produced Christian paraphernalia available online, ranging from playful novelties (smiling Jesus figurine giving a thumbs up, anyone?) to more poignant mementos. But the project is not merely about documentation: it’s a thoughtful commentary on how consumerism and religion intersect in contemporary society, she says, “where the market economy engulfs even the most sacred.”

The theme is reinforced in the accompanying 90-second film, where the objects are juxtaposed with clips of Chinese workers stringing rosaries on production lines and on-screen depictions of Jesus, as well as scenes from a televangelist special and an interview with Donald Trump about his relationship with god (“I try and do nothing that’s bad.”) Around the halfway mark, a voice announces the obvious: “Jesus sells.”

“Born for Such a Time as This” takes its title from a verse from the Book of Esther, in the Christian Old Testament. In its original context, the words are a reminder that we’re all put on Earth to serve a purpose as ordained by God, even when our situation seems dire. “I feel there is a parallel between this phrase, which speaks of stepping up to fulfill God's purpose…and these Christian objects,” Kyoko says. “The Bible says all things are done according to God's plan and decisions. If that's the case, then the crown of thorns and holy water sold on the internet are also part of his plan and made for God's purpose—I wonder what that could be?”

Kyoko traces her fascination with Christianity back to her childhood. Though she doesn’t identify as religious, she attended a Catholic missionary school in her native Japan, an hour outside Tokyo, before moving to London to study at Central Saint Martins. “School always started and ended with prayer,” she says. “We prayed before lunch, studied the Bible once a week, and attended Easter and Christmas masses in our school gym with a visiting priest.” And yet for all of the religious pretense, few of the students and teachers were actually Catholic. “I always felt strange to be in a Jesus-themed school where no one really cared about him. We were practicing these rituals without religious sentiment and it just felt like repetitive tasks.”

The experience provided an understanding of how easily religion can be divorced from its original intentions—a theme that reverberates in “Born for Such a Time as This.” Many of the names given to objects by their sellers (the wordy “Jesus Authentic Crown Of Thorns From Holy Land Jerusalem 20cm Christian Handmade” stands out), she notes, are more concerned with SEO than piety, designed to help sellers “desperate to rank on the first page on Amazon,” while one damaged Mary figurine she purchased couldn’t be returned because the seller had provided fake credentials and, later, deleted their account to avoid culpability.

Kyoko was also struck by the fact that so many of the products she purchased were manufactured in China, where the ruling Communist Party is officially atheist, and only 16 perfect of the population identifies as religious. In this context, these trinkets are “mere objects for profit, and the market economy endows them with a ‘sacredness’ to increase their value,” Kyoko says.

Today, it seems nothing is safe from commodification, no matter how at odds the mode of production might be from the message ingrained in the object being produced. But ultimately, Kyoko hasn’t explicitly set out to condemn religion or consumption, nor the people for whom they hold value. “I use the visual arts as a toolbox to investigate what intrigues me, and the resulting work is a record of my discovery,” she says. “By sharing it, I hope that people will feel the same sense of wonder that I felt discovering these objects and the circumstances surrounding them.”