Klaas Rommelaere is an artist who uses near-forgotten textile techniques like cross-stitch, crochet and classic knitting to bring neo-folkloric tapestries to life, but he doesn’t do it alone. The unconventional team he works with consists of mostly elderly ladies, scattered over various towns in Belgium – his so-called ‘madames’. Here, writer Rolien Zonneveld speaks to Klaas about his atypical working method, and what lies behind the explosion of surreal embroidered scenes.

All images courtesy of Galerie Zink.

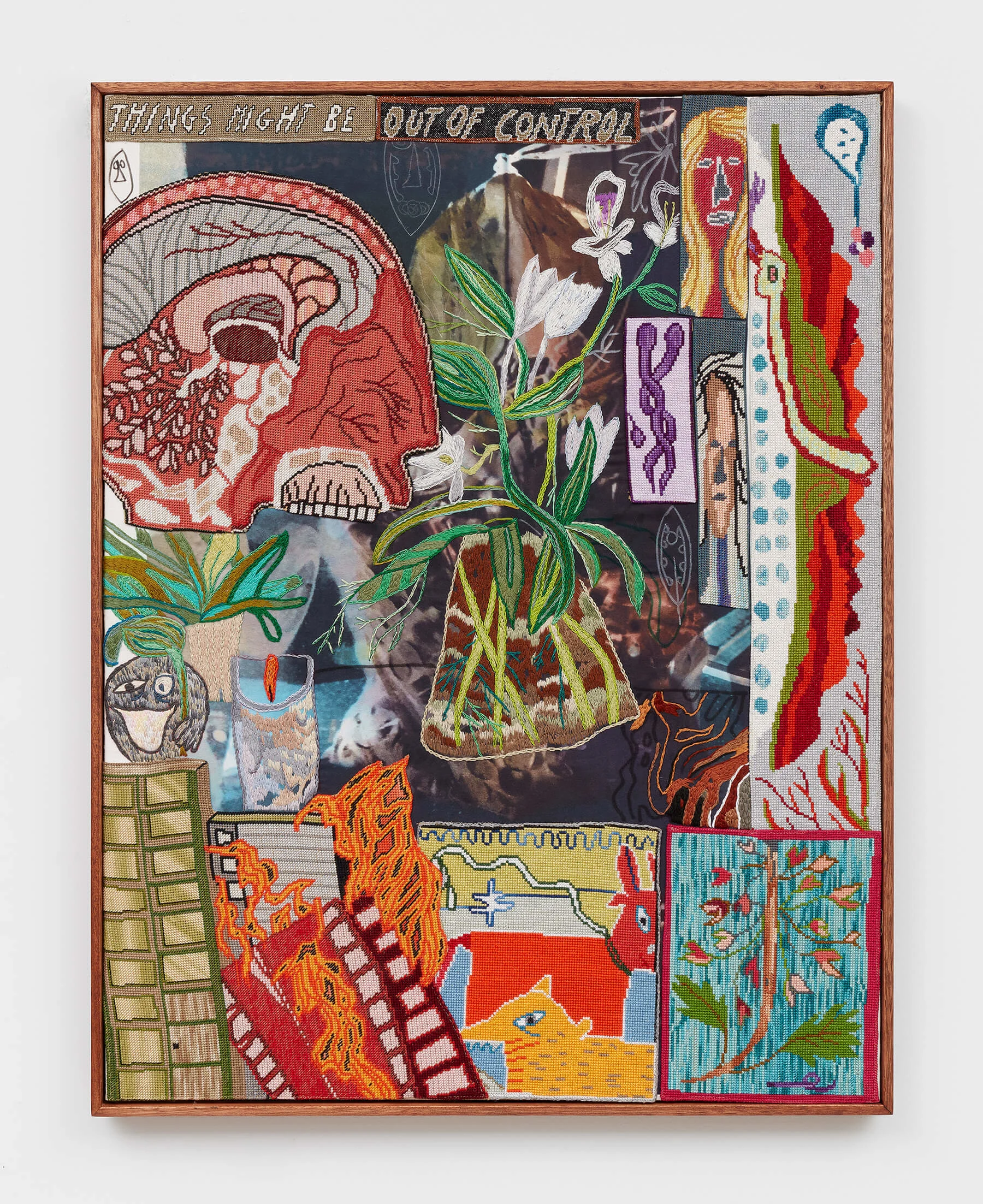

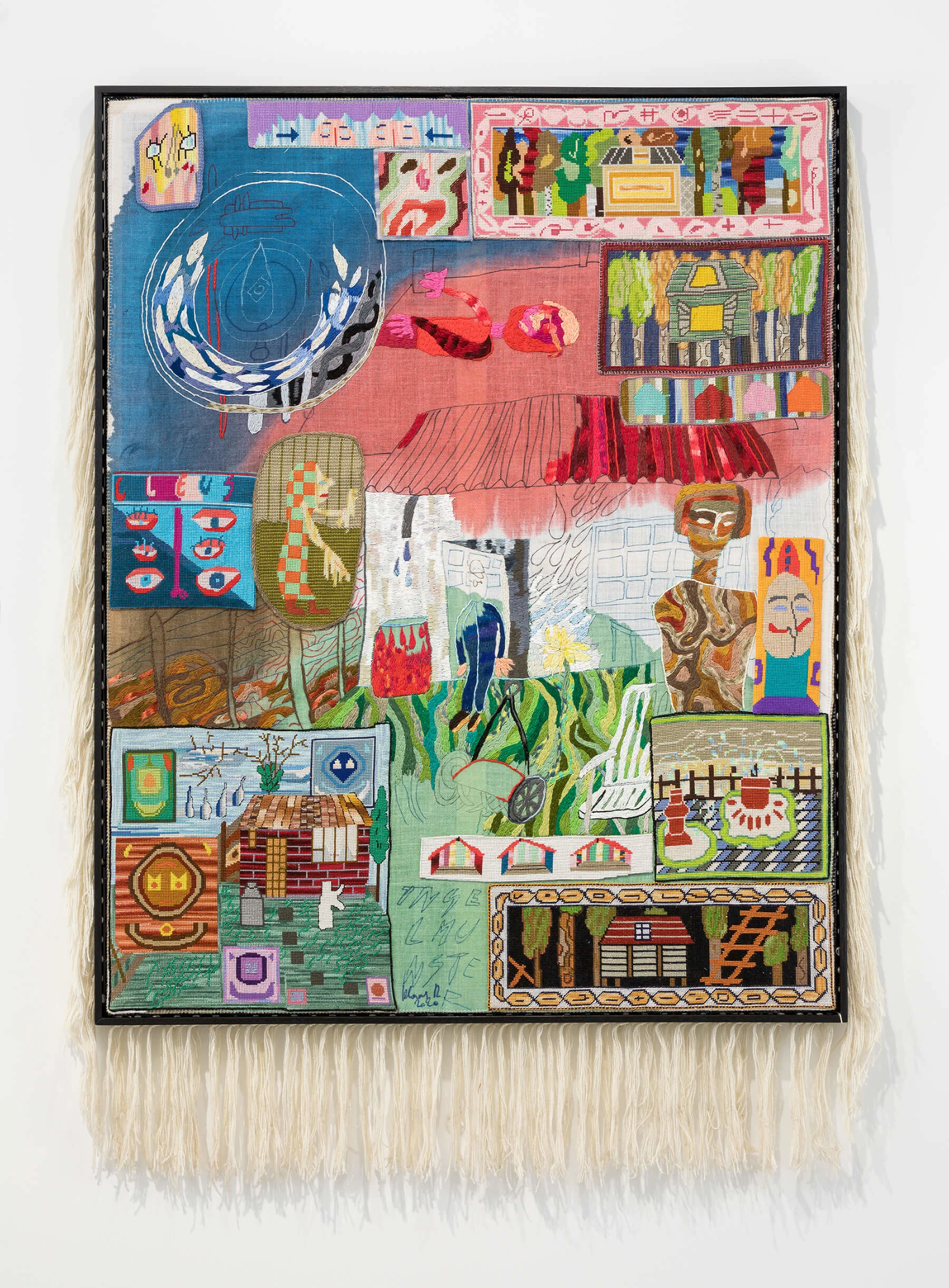

Over the last seven years an unlikely community has emerged in Belgium: scattered over several villages and cities, elderly ladies are gathering weekly to work on large-sized tapestries depicting surrealist, distorted scenes. Whether it’s a haunting memory of falling off a horse as a young boy, or an anatomical sketch of a brain, or characters from horror movies like “Hereditary,” the tapestries feel like a feverish peek inside someone’s mind. An explosive scrapbook of personal thoughts, memories and impressions translated onto cloth using needle, thread, wool and yarn.

The brain these scenes have sprouted from belongs to Klaas Rommelaere, an Antwerp-based artist who uses near-forgotten textile techniques such as cross-stitch, crochet and classic knitting to embody and personify themes like urban neo-folklore, heritage, and a quest for identity – with the support of a small army of what he calls his “madames.”

His visual language is rooted in everyday life as well as in pop culture: quotes from films or animations are intertwined with personal observations and experiences. The result is an assemblage of hundreds of layered, eclectic images. It’s reminiscent of Adam Curtis’ hallucinatory documentaries that attempt to untangle modern day phenomena – a recent source of inspiration to Klaas. At times the scenes feel nostalgic and gloomy, but elsewhere they’re colorful and light-hearted.

In 2021, the artist had his first solo exhibition entitled “Dark Uncles,”a loving homage to his friends and family in the form of life-sized dolls, tapestries and flags. Across the dolls’ bodies were numerous embroidered references to the person’s personality, hobbies, or professions. The snow-capped mountain peaks on father Dirk’s chest, for example, served as a reminder of the holidays in the Alps with the family. His mother is a speech therapist, so he embroidered an anatomical representation of the speech organs on her chest. Artworks that his grandfather used to make being an amateur artist are covering the doll’s body. On the doll personifying his grandmother, you’ll find a rug from a fisherman’s house they used to go to as a family every year, just off the Belgian coast.

Klaas’ career in textile started at the Royal Academy of Fine Art in Ghent, where he pursued a degree in fashion. Having done internships at renowned designers Raf Simons and Henrik Vibskov, he noticed how thin the line between fashion and art can be. At Vibskov for example, the fashion team worked in tandem with the art installation team. It was during that time that Klaas got his first taste of crocheting, which later would become the foundation for his entire practice. Abandoning the world of fashion almost immediately after graduation, he started to experiment with tapestries.

Handcrafting textiles, however, is a notoriously tedious and laborious process. The artist therefore first enlisted his grandmother, who he’s been close with ever since he was a child. “Throughout my studies, I would often go to my grandparents’ place to work on school assignments and collections,” he explains. “It’s an environment where I feel very at home and relaxed.” His grandmother also happened to have a vast knowledge of old-fashioned textile techniques that for decades were associated with “domestic work,” such as crocheting and cross-stitching. Now she had the opportunity to pass these skills on to her son.

“What irks me is that in our society, elderly people are often seen as a burden, as if they no longer ‘add value’, and they’re sometimes considered obsolete. People tend to forget, however, that a lot of these people have skill, time and patience, and more importantly, are still very creative,” he adds. Working with this grandmother allowed Klaas to start producing increasingly more ambitious textile works.

Next, he decided to find out if other ladies were interested in joining his creative process. He approached a couple of elderly homes, and around 15 women responded. To this day, those ladies – hailing from Flemish towns like Merksem, Roeselare and Ingelmunster – form the core team behind the execution of Klaas’ tapestries. “This might sound odd but I see them more often than I see my friends,” he says.

Rather than thinking of them as mere executors, however, he sees the women as integral to the designs. “It’s really interesting to see what happens when you compare your own work to that of a 90-year-old. In the past I’ve had interns who really wanted to make it ‘pretty,’ usually using a pastel color pallet. For me, that’s not how a work becomes compelling,” he says, explaining how the ladies are quite experimental and make their own aesthetic decisions on yarns and colors, as well as their own interpretations of his drawings. “They’re not occupied with whatever is ‘trendy’ and they don’t stylize their designs. They make something because they genuinely think it’s beautiful. It’s very refreshing, and the outcome is always surprising.”

While it hasn't been his intention to turn his work into a socially engaged art practice, it has in fact organically grown into a communal activity – creating both shared purpose and exchange. For “Dark Uncles,” the museum helped him put out a call to expand the group of volunteers, to which over 100 people responded. They were sent home-kits to help finalize the last bits of the project, and kept him updated via digital channels, as it happened against the backdrop of the global pandemic. Working on the project together while being apart acted as an antidote to a growing sense of isolation.

“Working on tapestries is meditative, and anyone who gets on board gets addicted,” he says. “It might sound cliché but I believe handcrafting textiles is a great way to deal with the fleeting, fast-paced world we inhabit, fuelled by the internet and social media.” Perhaps it’s time to join the crew.