WePresent has partnered with the Barbican to co-commission Sierra Leonean artist Julianknxx's new multimedia film installation “Chorus in Rememory of Flight.” For this piece of work, the artist traveled around Europe, exploring largely untold stories of Black and African diasporic realities and collaborating with local musicians and choirs. The project will be on show in The Curve gallery at the Barbican, London from 14 September 2023 to 11 February 2024.

In this part of his European journey, Julianknxx traveled to Berlin and Hamburg. Writer Debo Amon reimagines the troubled story of human zoos.

we carry the ocean with kite strings

tied around our waist.

— Julianknxx

It’s 1931 and there’s barely a cloud over Berlin. A young white couple decide to take their child to the zoo, as Hamburg-based animal trader and zoo director Carl Hagenbeck, is in the city with his touring show. A short while into their time at the zoo, they stand in front of a man called Kwelle, marveling at his difference, pointing out his hair, skin and other features to their young one.

As the couple’s attention is drawn to the plaque, reading its pseudo-anthropological text about Kwelle’s heritage, Kwelle reaches for his opera glasses to better examine the young family. The first to notice this is the mother. She gasps and immediately tears well up in her eyes. Next, the father, his face a kaleidoscope of emotions. He grabs the child as if Kwelle’s gaze will forever taint the innocence of his offspring. Kwelle holds his gaze on the family, as the couple descend into familial chaos, the wife crying, screaming to leave, to run from the amorphous sense of shame and embarrassment she feels, while her husband is caught between a growing swell of fear and violence. The child, confused by this scene, begins to wail, not for any fear of Kwelle, but rather in the subconscious realization that power is not fully vested in her parents, that it is not a birthright.

This is what I wish to imagine of the real Kwelle Ndumbe’s subversive acts of resistance in the face of the situation he and many others were forced into, in the human zoos of Europe’s not-too-distant past. It’s all too common to hear phrases like, “I don’t like to be labeled” or “boxed in” or “pigeonholed”, but being labeled, mis-labeled and unlabelled has been the literal reality for those on the receiving end of the colonial project for generations.

The movements of black people—not only as commodities but engaged in various struggles towards emancipation, autonomy, and citizenship—provides a means to reexamine the problems of nationality, location, identity, and historical memory.

— Paul Gilroy, “The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness” (1993)

Blood as a form of heritage is an inherently problematic one, especially when considered from Black perspectives. Race is a fiction built upon this foundation. A fiction that was then used to justify Europe’s colonial projects, and one that continues to fester in contemporary societies, from colourism to questions like, “but where are you really from?” It’s in this struggle that, as Gilroy states, a reexamination of national, local, and personal identity must be had. During his time in Berlin and Hamburg, Julianknxx encountered the challenges of heritage, belonging and inheritance head on, as the legacies of race, colonialism and blood heritage are found not just within the fabric of the cities, but also in the ways Black and Afro-German people navigate and relate to the cities and themselves.

Near the port of Hamburg across a building with a facade of stone is the word “AFRIKAHAUS”. Is this building a beacon against the Hamburg cold for those who know warmer climates? A place to find belonging? A sanctuary to gather strength, guarded at its entrance by a bronze Wahehe warrior just as in Lugalo? No. Some would call it an office, a headquarters for the C.Woermann company. Others an archive of pain and profiteering built on the establishment of German colonies in Africa; on murder and brutality; on genocide and concentration camps. There are no secrets here, or contested truths. There is no shame, no sense of irony, no mea culpa. I call to mind Dr. Maya Angelou’s advice: “When someone really shows you and tells you who they are, take them at their word.” I take this to heart, knowing that for many of the beneficiaries of Europe’s colonial histories, the past represents halcyon times and the only issue is that it’s not the present. In 1970 Gil Scott-Heron asked “who’ll pay reparations on my soul?” I hear that question still echoing today.

When speaking to poet Justice Mvemba, Julianknxx asked about the history of Berlin’s Africa quarter. Justice spoke about how rather than it being an indication on the origins of its residents, it was instead 22 streets dedicated to colonial regions and their former colonial actors.

While Germany’s colonial empire apparently ended in 1920, at the end of the First World War, and the human zoos of Berlin and other German cities stopped in the 1930s, it’s fair to say Berlin is a city of microaggressions. How do you live when resistance is a daily requirement? For Justice, her answer is to write. An exercise which I perceive as inherently hopeful, as to write, even just to yourself, is to think or hope that you will be read, listened to and maybe even understood. This was borne out in Justice’s conversation with Julian, as she shared a poem for the first time—a moment of vulnerability that even for me as a listener, eased even if just for a moment, the weight of resistance.

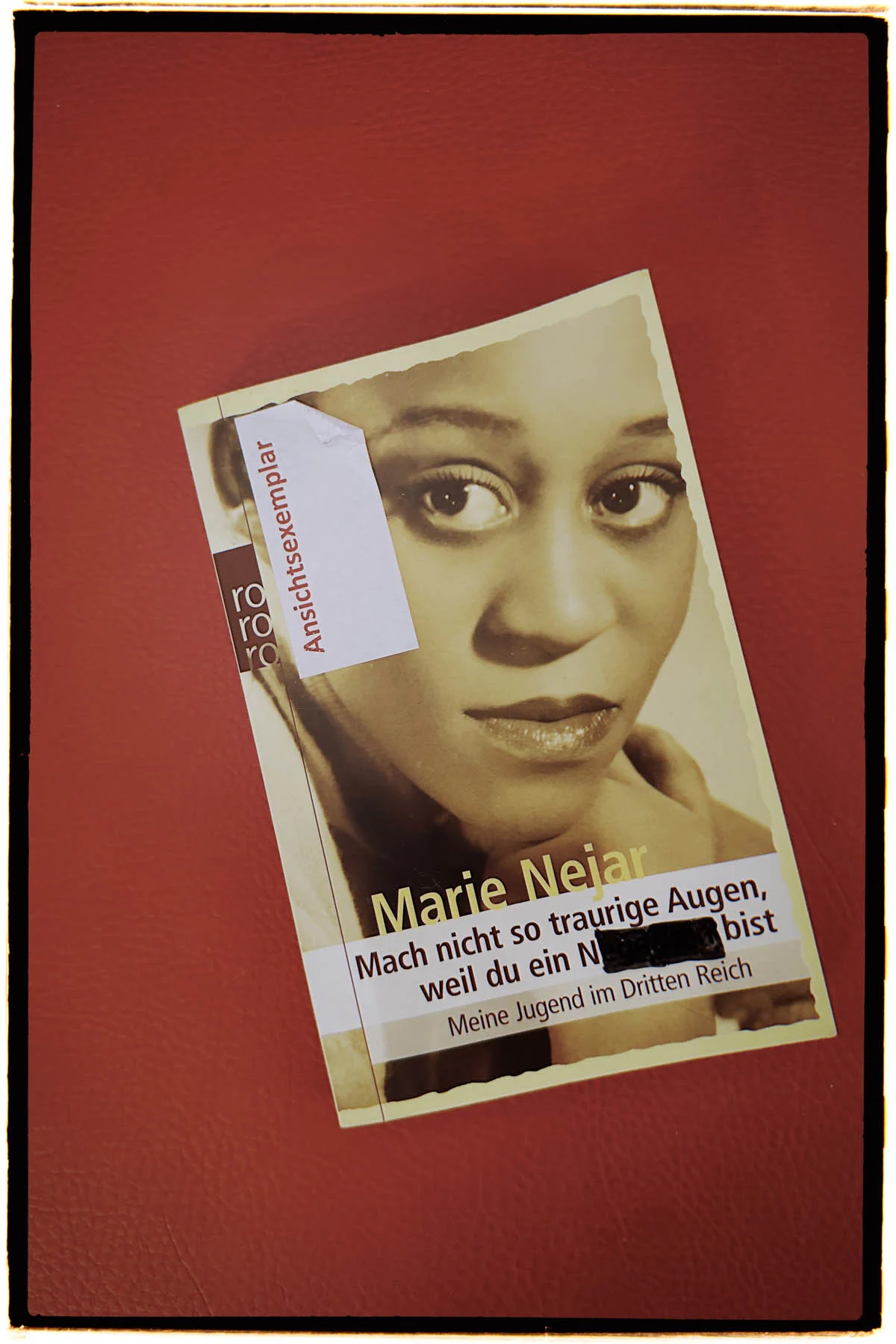

Considering Kwelle Ndumbe’s acts of resistance, it’s fitting that 1980’s Berlin also became a site for a new generation of Black resistance. This time led by Black women who formed collectives to develop their ideas and frameworks beyond singular, individual acts of resistance toward collective, intersectional and sustained movements. It’s hard to overstate the importance of this moment, the first published book by Afro-Germans came out of this movement, “Showing Our Colors: Afro-German Women Speak Out” edited by May Ayim and Katharina Oguntoye. The audio below is a section of Julianknxx’s interview with writer, historian and founder of intercultural network Joliba, Katharina Oguntoye. Ogutoye speaks to Julian about the first ADEFRA (Black Women in Germany) meeting in 1986, where they spoke and reached a consensus on self-identifying as Black/Afro-German.

“We thought Afro-German could be a good name to refer to our upbringing and not to the blood heritage, because in German nationality until a few years ago, it was always about your blood heritage. And we said, no, it has nothing to do with the blood heritage. It has to do with being raised here. Having grown up in this culture, sometimes you’re acknowledged and sometimes you’re even ostracized, but you are raised here.”

— Katharina Oguntoye

This act of self-identification and exploration is at the heart of Julianknxx’s “Chorus In Rememory of Flight”, and also reminds me of the connection between Julianknxx’s work and the women who have paved the intellectual, social and artistic foundations upon which it stands. It’s important to understand the gaze through which we look at ourselves and the world around us. To know what representations of us are our own and those that are reflections not of us, but of an ideology, or perspective, that centers ideas and forms of power based in oppression. But to constantly live under pressure to either assimilate or resist through the daily assertion of your own identity takes its toll, even on the actions and interactions between Afro-diasporic communities.

Yet, here the template left by ADEFRA reemerges as a reference point on overcoming the isolating effects of the pressures of resistance of Western value systems that may not serve Black and Afro-Germans. Returning to the collective and the ways in which these women choose to resist and subvert the challenges which Black and Afro-German people face is beautiful and also unsurprising when I consider the lineages of resistance on which they stand. Audre Lorde spent significant time in Berlin in the 60s, and the use of the term Afro-German was actually her suggestion to Katharina and the other members of ADEFRA. Focusing on intersectionality and alternative value systems so as to try to not to recreate the oppressions they face, feels to me a direct result of a continual process of reexamining and meeting the issues of race, colonialism and blood heritage.

“For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us to temporarily beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. Racism and homophobia are real conditions of all our lives in this place and time.”

— Audre Lorde

As Julianknxx writes, “we carry the ocean with kite strings tied around our waist”. We do this not only as individuals but also together. A connection not founded in blood, but in a joint struggle toward emancipation, casting our gazes, as Kwelle Ndumbe did, back on the problems of nationality, location, identity and historical memory, with new tools to dismantle that which does not serve us.

Explore Julianknxx’s experiences in the seven cities he visited to make “Chorus in Rememory of Flight”

“Chorus in Rememory of Flight” has been co-commissioned by the Barbican and WePresent by WeTransfer in partnership with Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and with support from De Singel.