WePresent has partnered with the Barbican to co-commission Sierra Leonean artist Julianknxx's new multimedia film installation “Chorus in Rememory of Flight.” For this piece of work, the artist traveled around Europe, exploring largely untold stories of Black and African diasporic realities and collaborating with local musicians and choirs. The project will be on show in The Curve gallery at the Barbican, London from 14 September 2023 to 11 February 2024.

In the first part of his European journey, Julianknxx traveled to Antwerp. Writer Debo Amon tells the story of the severed hands and explains how it’s still a significant part of Antwerp’s culture. What does a nation do when it's made aware that it may not be the hero?

ask those who came by water.

Where did all the hands go?

— Julianknxx

On the morning of Monday March 9 2015, Chumani Maxwele traveled to Khayelitsha, a township in the City of Cape Town, South Africa, to pick up a bucket of shit. Maxwele had a question to ask and he wanted to make sure it was heard. He returned to the University of Cape Town where he was studying political science and asked a small, gathering crowd of students and press, “where are our heroes and ancestors?” He then proceeded to throw the bucket of shit onto the face of the statue before him. The university’s statue: a statue of Cecil John Rhodes, the British Imperialist and mining magnate.

This was the first of many questions posed by what would become the protest movement Rhodes Must Fall. The movement spread through campuses around the world and reignited broader conversations about decolonisation and what that means. Its echoes can still be found within the chants of Black Lives Matter and even within the curriculum changes in Belgian schools. It wasn’t the answers, or lack thereof, to Maxwele’s question that proved so powerful and contentious, it was the perspective from which the question came from that caught people’s attention—something the best questions have in common.

So, where did all the hands go? This is the question Julianknxx returned with from his time in Antwerp, Belgium. A question that pokes at the heart of a nation’s history, a city’s mythology and at the very name “Antwerp”. Our myths and legends are the ways we tell ourselves and others about ourselves, about what we hold dear, what we fear, what we love and what we are proud of. This is no different in Antwerp.

Group myths are inculcated; they aren’t made to be questioned or interrogated, but rather they help define the group itself, as those within supposedly understand their place in relation to these myths, implicitly. Take the myth of British stoicism, the stiff upper lip and ask yourself where was this stoicism among a nation’s football fans when Marcus Rashford, Jadon Sancho and Bukayo Saka missed their penalties in the UEFA Euro 2020 final? This ability to create group identity is particularly useful in helping establish communities, by giving strangers a shared “history” that binds them in a sense of familiarity and fraternity.

Yet Antwerp, as with many other European cities, hosts a significant population of people whose real histories don’t intersect so easily with the city’s mythological one. If you were aware of the history of Belgian colonial rule, it would be hard by any stretch of the imagination to conceive of Belgium as the hero in their tale of the giant Antigoon. The story tells of a giant who guarded a bridge over a river in Antwerp and terrorized sailors by cutting off their hands—until a Roman soldier named Brabo cut off the giant’s hand in return and threw it into the river, killing him.

Brabo is celebrated as a hero in Belgian culture, a belief that positions themselves as a nation of just giant slayers. This is the power of our stories and the seduction of equating victory as moral superiority.

“Where did all the hands go” asks what does a nation, a city, a community do when they are made aware that they may not be the hero of their own stories? Or that the hero may himself be a villain, at least to some? What happens to the people who make them aware of this? What happened to those made monsters and savages to justify brutality and death?

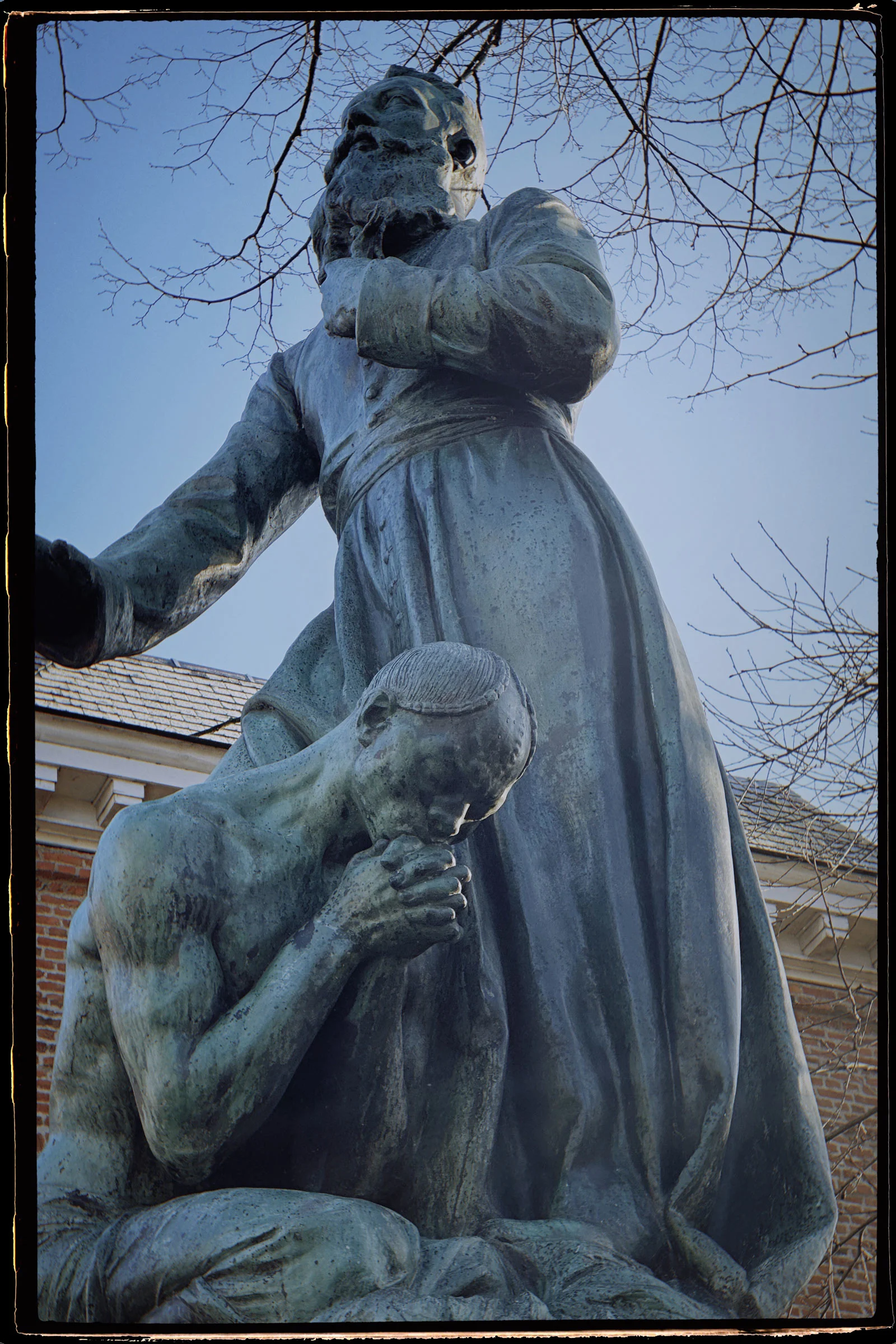

The following voice note by Julianknxx to myself was sent while he was filming and conducting interviews in Antwerp. He talks to me about the conversation he had just had with the historian Omar Ba in Antwerp. I’m struck by his reference to two things: first, his summation of Omar’s perspective on the influence of colonial education on Léopold Sédar Senghor, the first president of Senegal; and, secondly his reference to a statue, which we both later come to know is the sculpture of Father Constant De Deken with his knee on the back of an unnamed Congolese warrior, below.

When I look at this sculpture of a Congolese warrior kneeling in prayer with the knee of Father Constant De Deken, a colonial missionary, on his back, my mind asks many questions. I wonder about his name. His name, not the one they call him. I wonder if he prays, there on his knees, to their god with their name. Whether he could be recognised by their god with that name and his face. Was he lonely without the comfort of his ancestors and their gods? Their beliefs were made dirty and foul, and so left in the dense thicket of the bush, where he was told death resides, though salvation had the same stench and the knee on his back the same weight.

I’m reminded of the last time I cried in a room of white people—December 2018, watching Dania Gurira’s “The Convert”. It’s a play that explores the use of religion and language as tools of colonialism. I remember Ester…no…I remember Jekesai Wekwa Chiyangwa Murumbira. I remember what she said:

“The whites don’t do what their book is saying. I thought they would be like Jesus, show his love, love their enemy, I thought—”

I remember.

In the following two voice notes, you first hear me respond to Julianknxx’s previous note moving our conversation on to the repeating symbolism of hands in relation to Antwerp, and Belgium at large. He muses on hands as a metaphor for what was taken, what was lost and what was forgotten from the perspective of Africans who were colonized and us, their descendents.

When I look back on 2003, I wonder if American President George W. Bush and British Prime Minister Tony Blair were listening to 50 Cent’s debut album “Get Rich or Die Trying”. I certainly was, as was almost everyone I knew from London to Lagos. It soundtracked my final year in secondary school, my summer in Lagos and the collective dreams of money, parties and brotherhood among my friends and I as we rapped along, beating our chest and gesticulating for emphasis. 50 Cent had seemingly burst onto the scene by turning his personal history into public mythology. One of the stand out songs on “Get Rich or Die Trying” is “Many Men”. On it, 50 Cent laments how many men are trying to take his life away. The song is filled with somewhat understandable paranoia given he was famously shot nine times, yet survived. He uses the song to set himself as both a victim of jealousy and circumstance but nonetheless a hero. He never seems to consider that maybe the choices he makes in his paranoia are contributing factors as to the acrimony “many men” seemingly feel towards him.

For me, this positioning of oneself as both hero and victim, is particularly resonant with my memories of Bush and Blair’s justifications leading up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, which consequently was just a month after 50 Cent’s album was released.

“We cannot put our faith in the word of tyrants, who solemnly sign non-proliferation treaties, and then systemically break them. If we wait for threats to fully materialize, we will have waited too long.”

— President George W. Bush, speech at U.S. Military Academy (West Point) on June 1, 2002

In this speech Bush laid out his justification for preemptive war while Blair made similar statements. Both—much like 50 Cent—describe a world of untrustworthy tyrants just waiting for their chance to do us harm. The consequences of such an attack would be dire, so we must strike first. In hindsight we know there were no weapons of mass destruction to be found in Iraq, and that there were retroactive justifications for a continued occupation of the country. It strikes me that as with 50 Cent both Bush and Blair had created their own heroic mythologies and through sheer force of will seduced their respective nations into an unfounded collective narrative.

I wish heartbreak wasn’t so familiar, but as it is, I know each heartbreak requires its own ode. Listening to Julianknxx interview Junior Akwety (Antwerp chorus member) and Shamisa Debroey (programmer, creative communities at DE SINGEL international arts center, Antwerp), it was clear to me, one would not be enough, not for them or for those who know the same struggle.

Since before I can even remember, when speaking of immigration, politicians, papers and pundits have all spoken of tolerance. Yet, little is said about how it feels to be tolerated. Akwety speaks of the burden of not being seen as an individual in Antwerp but as part of a group of guests whose welcome is very much conditional. “I need to be the ‘perfect’ version of myself in order not to ruin it for somebody else that’s going to come behind,” he says. How can anywhere or anyone feel like home if perfection is required? Debroey also spoke of this toil. Of the temporary reprieves of achievement and of the recoils of hard lived realities: “Every now and then, it’s like we can smell freedom, or we feel equal, and actually it’s a trap. It’s an illusion. It’s not reality.” She goes on to ask, should we be working separate from the system?

Debroey’s question is one I’ve asked myself, a thousand times, and had a thousand discussions with family, friends and peers about. This question is no stranger to us. So, I ask another: why do we carry on? Striving, fighting, looking for love? I began writing this while listening to Akwety’s song on repeat, yet at some point his voice and their words drove me to another song, Frank Ocean’s “Bad Religion”.

If it brings me to my knees

It's a bad religion

This unrequited love

To me, it's nothing but a one-man cult

And cyanide in my styrofoam cup

I can never make him love me

— Frank Ocean

As I said, I’m no stranger to heartbreak, though this wasn’t a reference to my romantic life. In this life there are many heartbreaks to be had, but trying to make home of a place that doesn’t love you, but rather tolerates you, makes me wonder if this is a poison we continue to sip, for faith that maybe one day we can make them love us. In Akwety’s words: “Everything I try to do, I don’t take it too seriously, but I take it with the intent of making an impact that people remember that it’s okay to have us around, to have us doing stuff, but to have us also progress.” It’s here I find my answer to why we carry on, and also another heartbreak.

We carry on because we have been carried by our ancestors, and if fortunate, by those with us now, a burden born of love given freely in the hope it will be passed forward. As Shamisa Debroey puts it, “I think if you ask people who I am, they’ll always say Shamisa’s a fixer. She’s someone who opens doors. And I love that definition of me. It is very important for me that people know that if I can bring someone, I always will.” Hearing this, leads me to think, perhaps we have an answer to where did all the hands go?

As with Debroey and Akwety, those who are left are busy building new realities for themselves and others, sipping poison so hopefully those who come after won’t have to.

Explore Julianknxx’s experiences in the seven cities he visited to make “Chorus in Rememory of Flight”

“Chorus in Rememory of Flight” has been co-commissioned by the Barbican and WePresent by WeTransfer in partnership with Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and with support from De Singel.