According to José Morbán, the Dominican dream is the longing to emigrate north to the US in search of a better life. He always felt it wasn’t his place to talk about immigration, since he hasn’t experienced it himself, and so he started to think about the idea of the Dominican dream less in a literal sense and more in a wistful way. He associates it with an idealized nostalgia, something he feels his country is prone to, remembering its history as better than it was.

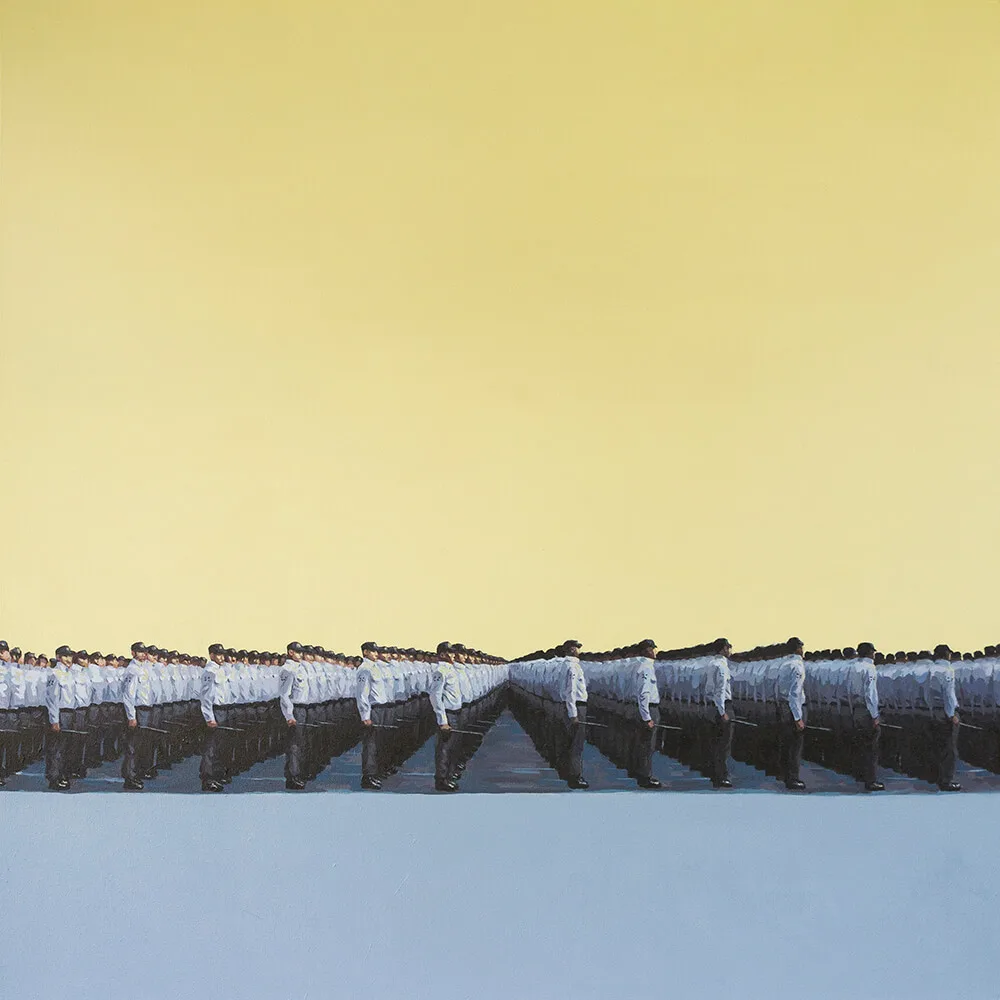

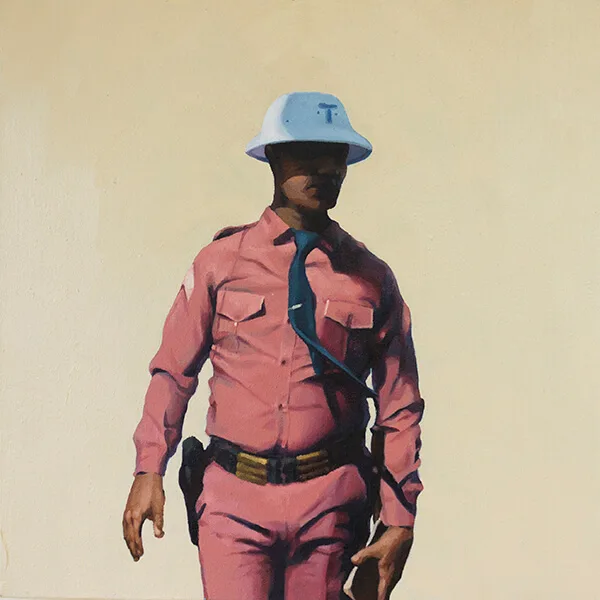

His series Dominican Dreams is made up of paintings of moments from the country’s past. Subdued in colour, they have a vintage feel to them, yet without the wear and tear of older imagery, they have a crispness that appears fresh and new. There’s an anonymity to the paintings with few clear faces shown, as José tries to capture these moments using peripheral figures, without making obvious references to the key people involved.

Before putting brush to canvas, José did a considerable amount of research. “I was in the national archives, books, and of course the internet, collecting photos from various decades of Dominican history,” he says. “I processed them digitally; coloring, cutting and multiplying to repurpose the image or amplify its meaning.”

The country has a turbulent past, flitting between independence and being a colony, including three centuries of Spanish rule which ended in 1821. After just a few months though, the Haitian government invaded the newly independent Dominicans, who had to win back their independence once again 22 years later.

Since then, the country has witnessed US military interference, various uprisings and short-lived governments, until 1930, when Rafael Trujillo was elected president with little opposition following a violent campaign. His strict dictatorship lasted until 1961, when he was assassinated with the help of the US authorities.

José’s work is almost always focused around his homeland. “There’s no way to separate my work from my personal history,” he says. “Being from a country with such a fractured historical memory it’s inevitable, as an artist, to reflect on it at some point.” The series highlights the way the country has worn a mask in the last century, hiding behind images and propaganda that sells its flaws and problems as power and success.

The story behind one of the works in the series, Güibia (c.1943), underlines this point. “This is a painting of a photograph by Kurt Schnitzer, an Austrian-Jewish photographer who arrived in the country during Trujillo's dictatorship, and who later became Trujillo’s personal family photographer,” he says. “The way he documented the Santo Domingo of the late 1930s and early 40s eludes the misery and violence of those years.”

Schnitzer’s work is widely seen as a reliable window onto the era. By painting a photograph by the propaganda photographer, José reignites the conversation around his dependability. Instead of painting the most pivotal moments in the country’s history, he recreated stories he felt needed revisiting.

I wanted to paint these tropes of men that defined my own concept of power.

The country’s warped ideas of masculinity and power run through José’s work. “I wanted to paint these tropes of men that, positively or not, defined my own concept of power,” he says. “And these are moments that seem to repeat themselves today.”

José feels that Dominicans are tied to an idea of masculinity embodied by Trujillo, and this didn’t disappear once the dictator was killed. For example, the military parade depicted in Desfile (2017) still takes place every February in the Malecón of Santo Domingo.

What comes across in José’s image as a proud, positive scene is in fact a performative ritual defined by the strange power dynamics of clout-hungry men. “It’s not only an expensive demonstration of man-power, but a useless one if you consider that the first and last war we fought since our independence was in 1965.”

Ultimately, José wanted to look again at certain moments that had been packaged up and brushed under the carpet. “I wanted to represent our own passivity towards the construction of these political figures and their discourses,” he says. The result is a set of paintings that are not only beautiful to look at, but that have a huge amount to say if you know how to listen.