We’ve had decades of cinema and pop culture that uses weight as a gag or an indicator that a character is evil or shameful, incorporating fat suits and make-overs to share their insidious worldview. British filmmaker Jeanie Finlay defies that with her documentary “Your Fat Friend”. Writer Anna Bogutskaya meets Finlay to discuss why she made this game-changing film and the challenges facing people who experience the world in a “fat” body.

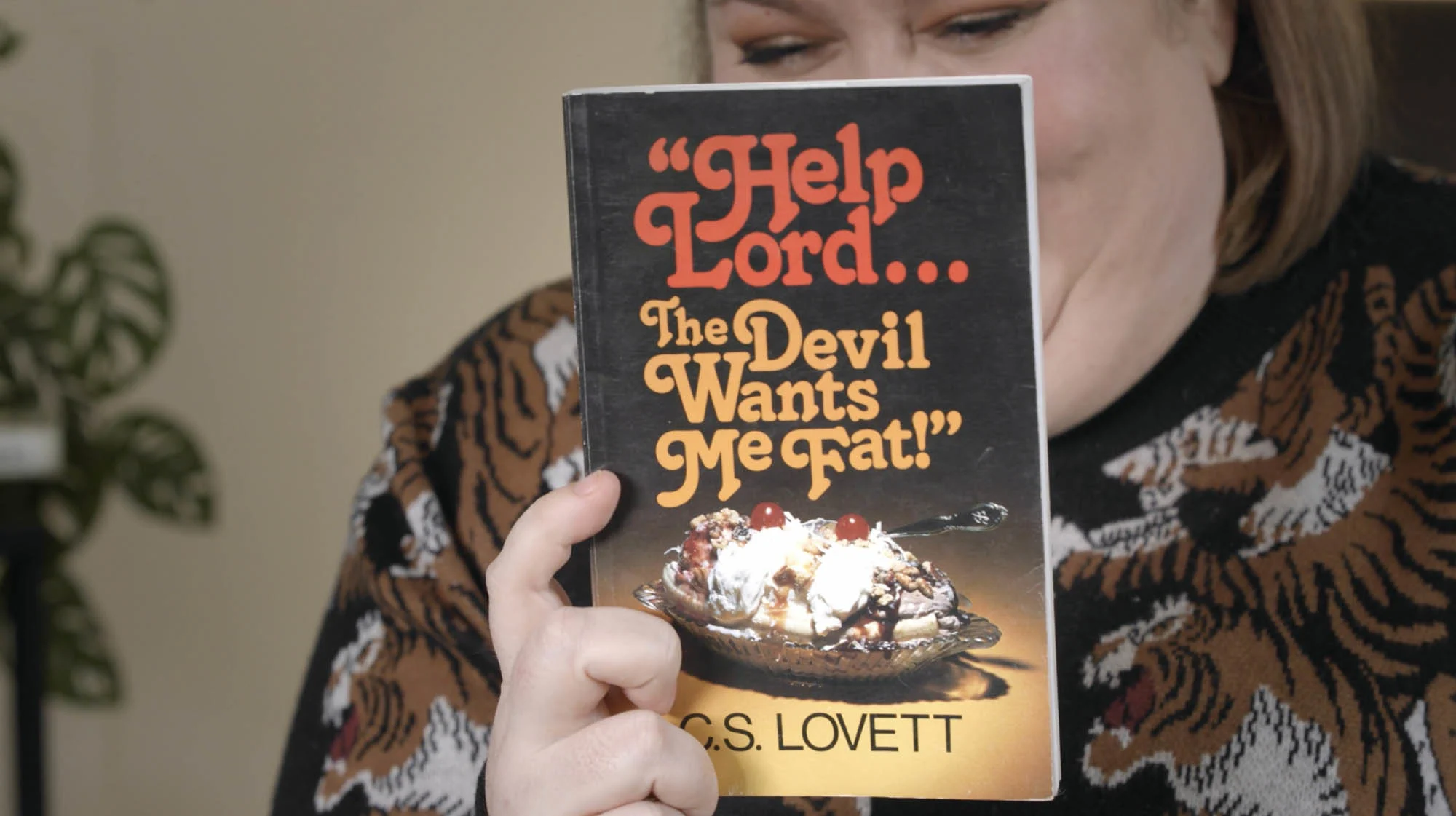

By the time I graduated high school, there was not a single girl in my class that left without a disordered relationship with eating of some kind. We were all running away from being labeled ‘fat’, a word that used as a barbed insult, a shameful label, instead of a mere descriptor. Anti-fat bias has shaped our view of the world, and pop culture has had a significant role to play.

Film’s relationship with fatness is one of grotesque reductiveness. Fat bodies are traditionally used as a source of humor or disgust. In either case, fat people on screen have to be punished. “Shallow Hal” (2002), a supposed rom-com that shows a fat woman’s inner beauty (actually just Gwyneth Paltrow in a fat suit) manifests as thinness (just Gwyneth without the fat suit). The “Austin Powers” trilogy has a villain named Fat Bastard (played by Mike Myers in a fat suit). Eddie Murphy made playing multiple fat characters for ridicule and laughs his meal-ticket with “The Nutty Professor” (1996), “Nutty Professor II: The Klumps” (2000) and “Norbit” (2007). Murphy plays near every Klump (except the young grandson), showing them all at a dinner table heaving with food, drowning their plates in gravy, farting at dinner and choking on chicken wings. The only actually fat character, the grandson, played by Jamal Mixon, doesn’t get a single line.

Many times over, a thin character will be humiliated by their past as a fat person (take a stand, Fat Monica from “Friends”, Fat Schmidt from “New Girl”). “Fatness has long been associated with moral failing or overindulgence, particularly in America,” writes Hannah Strong in Gawker, with fat characters in films and TV often defined exclusively by their size, and the narratives built around shaming or scorning them for their bodies. In recent years, the use of fat suits by slim actors has been heavily criticized, a conversation that reached its crescendo in 2022 with the release of “The Whale”, where Brendan Fraser plays a depressed shut-in who weighs over 600 pounds. Marvel’s “Avengers: Endgame” (2019) portrayed famously buff Chris Hemsworth in a fat suit to play a sulking Thor, and martial artist Scott Adkins was put in one for this action scenes in “John Wick 4” (2023). It’s funny, geddit, cause they’re fat action stars.

More positive representations have sprung up: grassroots Instagram account fat in film, which pays tribute to fat characters and actors, from Ursula in “The Little Mermaid” to Da’Vine Joy Randolph red carpet looks; and shows like “Shrill”, based on Lindy West’s memoir, is a delightful additional to the messy millennial canon starring Aidy Bryant. Some characters exist without their fatness ever being mentioned or impeding their stories, like Ruby Hill (Retta) on “Good Girls” or Cherise on “High Fidelity” (Da’Vine Joy Randolph).

It’s like showing your knickers in public with this additional layer of personal escalation that feels really exposing.

This is the state of pop culture in which “Your Fat Friend” arrives. The latest project from Nottingham-based documentary filmmaker Jeanie Finlay, it is a portrait of Aubrey Gordon, a New York Times-bestselling author and co-host of the monumentally popular podcast Maintenance Phase, and a glimpse into the experience of living in a fat body. When we meet for coffee in New Cross, around the corner from Goldsmith’s University where she’s about to do a guest lecture, the film is a week away from premiering at Tribeca. “It’s terrifying,” Finlay tells me. “It’s like showing your knickers in public with this additional layer of personal escalation that feels really exposing”.

Finlay’s filmography is a series of portraits of outsiders trying to connect. “Sound It Out” (2011) looks at the very last surviving vinyl record shop in Teesside, North East England. “Orion: The Man Who Would Be King” (2015) follows the rise and fall of a masked singer masquerading (or not?) as Elvis. “Seahorse” (2019) is an intimate portrayal of a trans man deciding to become pregnant and give birth. She shot this at the same time as “Game of Thrones: The Last Watch” (2019), an HBO-commissioned chronicle of the last season of the fantasy epic.

“Your Fat Friend” started when Finlay wanted to make a film about the changing narrative around fatness, the meaning the word ‘fat’ holds and how that meaning has changed, coinciding with the rise of Instagram. Empowered by social media, people were talking about fatness in a new, visible way, untarnished by shame: “Fat is a word and a label that held personal meaning to me, being a fat kid,” she says. More broadly, she wanted to engage in “the way that people in larger bodies experience bias.” Finlay spent years researching, meeting people and filming, but nothing felt quite right until she met Aubrey.

Finding the right person to be in her films is a really important part of the process for Finlay. “I just don’t want the people who’ve already told their story, that’s not interesting to me at all, what a waste of all of our time.” When she first met Gordon, she didn’t yet have a successful podcast or a book deal, she had a blog. What attracted Finlay was “the fact that she was a woman on her own”. Every writer has their own routine, and Gordon’s was to drive in her tiny car and occasionally stop and write. Finlay loved the image of “this fat lady driving around looking at the world”. Gordon’s writing, deeply personal, and at that point published anonymously, connected with her. “There was an enormous disparity between her work in the world and her as a person, and also her work in the world, her as a person and her family and how they dealt with the work she was trying to do,” she says, “It’s in the gaps where the film lies.” She showed up at Gordon’s doorstep in her house in Portland and started filming. Very quickly, the film became about her.

I’ve always really thought carefully about the things people are depicting on screen and I want them to recognize themselves, for good and for bad.

“I do worry that my own experience of my own body is coloring my filmmaking,” Finlay explains. “And filmmaking is too serious, too long and expensive a process to make something that’s purely partisan.” What’s different this time around is the in-built, global audience that Aubrey Gordon brings. Since they started filming, Gordon’s visibility has exploded, especially after the second book, “You Just Need to Lose Weight”: And 19 Other Myths About Fat People”, came out, while Finlay was editing. “Your Fat Friend” ends at the start of this, with Gordon’s first public book event in her beloved Powell’s bookshop. There is a long queue of people, mostly women, aching to tell her their stories, and how her writing has connected with them. It’s not just the teething pains of becoming visible, like Finlay originally thought, but “actually witnessing the relationship that people have with her because of what she’s talking about. I think it’s a very, very deep personal connection.” It’s a lot to carry for one person.

The film illuminates, through Gordon’s work and experiences, the narratives that shape our relationship with our bodies. There’s the media, there’s movies, but Finlay is interested in something more fundamental: “the most potent storytellers in our lives are our family. So, meeting her family, meeting her dad, who was unable to say the word fat, who hadn’t read anything she was sharing… it was just wild to me. Here’s a woman who is trying to enact a paradigm shift and it's connecting with so many people. What does that mean when your family is on a different journey? Can you reach them?”

Gordon’s family—her mom, dad and step-mom—are featured players in the documentary. “The film in a way is her parents’ journey, coming to terms and seeing and hearing what it means for Aubrey to live in her body.” “Your Fat Friend” has moments of gorgeous stillness, with Gordon floating in water, a space that has provided her with genuine joy, but that she is reticent about. She doesn’t swim anymore, because it’s “more work than it’s worth”. In terms of the technical filming process, Finlay wanted to “light her like a luxury bitch, lavish time and attention on her body.”

“I’ve always really thought carefully about the things people are depicting on screen and I want them to recognize themselves, for good and for bad,” concludes Finlay. “It’s not all peachy, as no portrait is going to be. It should feel a bit uncomfortable.”