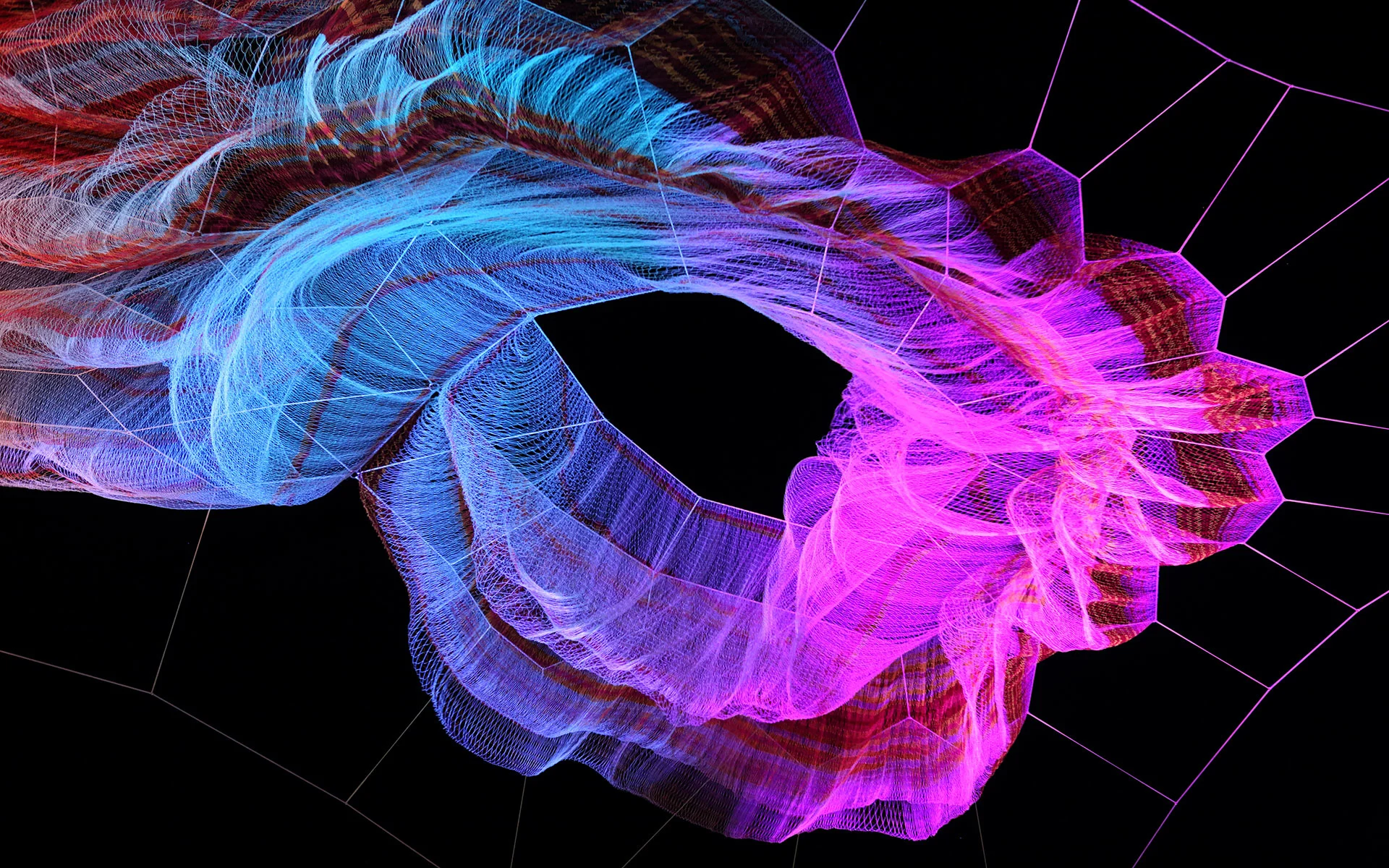

We all know that feeling of being so busy that we don’t even take time to give nature’s wonders, like the sky, a second look. However, when you encounter Janet Echelman’s gigantic and colorful installations, there’s a good chance you can’t resist; they majestically float above you, changing shape and color with the wind’s every caress.

Janet Echelman is a well-established American sculptor with installations all over the world. She works closely with a large multi-disciplinary team to hoist her gorgeous inventions in the air. We spoke to her about the challenges she has overcome along the way, the process of making a piece and the importance of art in the urban space.

What is the most amazing thing you learned you’d never thought you’d be learning when first starting out?

I was a painter for more than a decade, so the fact that I now create monumental, floating sculptures would be uncanny to myself as a 20-year old painter. I’ve learned so much about creating large-scale, aerial, soft-bodied sculptures in public space – all things very different from my earlier work.

When I traveled to India to present a series of exhibitions for the U.S. Embassy, I shipped my custom paints and tools to India. The deadline for the shows arrived – but my paints didn’t. I was in a terrible bind, with no materials to make my art. I walked along the beach, watching the fishermen bundling their nets into mounds on the sand. I’d seen it every day, but this time I saw it differently – a new approach to sculpture, a way to make volumetric form without heavy solid materials.

My first satisfying sculptures were made in collaboration with those fishermen. I discovered their soft surfaces revealed every ripple of wind in constantly changing patterns and I was mesmerized.

Can you walk us through the process of creating your large-scale installations?

Each site is a guiding force for the artwork. When I make the first site visit, I get a feel for its space, talk to the people who use it and spend time uncovering its history and texture to understand what it means to its people.

I work with my studio colleagues to brainstorm, sketch and explore, without censoring our ideas in the early stages. As the sculpture designs begin to unfold, our studio’s architects, designers and model-makers collaborate with an external team of aeronautical and structural engineers, computer scientists, lighting designers, landscape architects and city planners to bring my initial sketches into reality.

It is a gradual, collaborative and iterative process from every angle, and often takes more than a year to go from idea to the final artwork.

What is the most challenging part of creating a piece?

Finding the vision that completes each site – the right idea, the aesthetic form and optimal proportion, and a sequence of color that all speak to the pre-existing site — this is hard every single time. It’s difficult and unpredictable, and I suppose that is precisely why I love it; it keeps me on my edge, always pushing me into the uncomfortable zone.

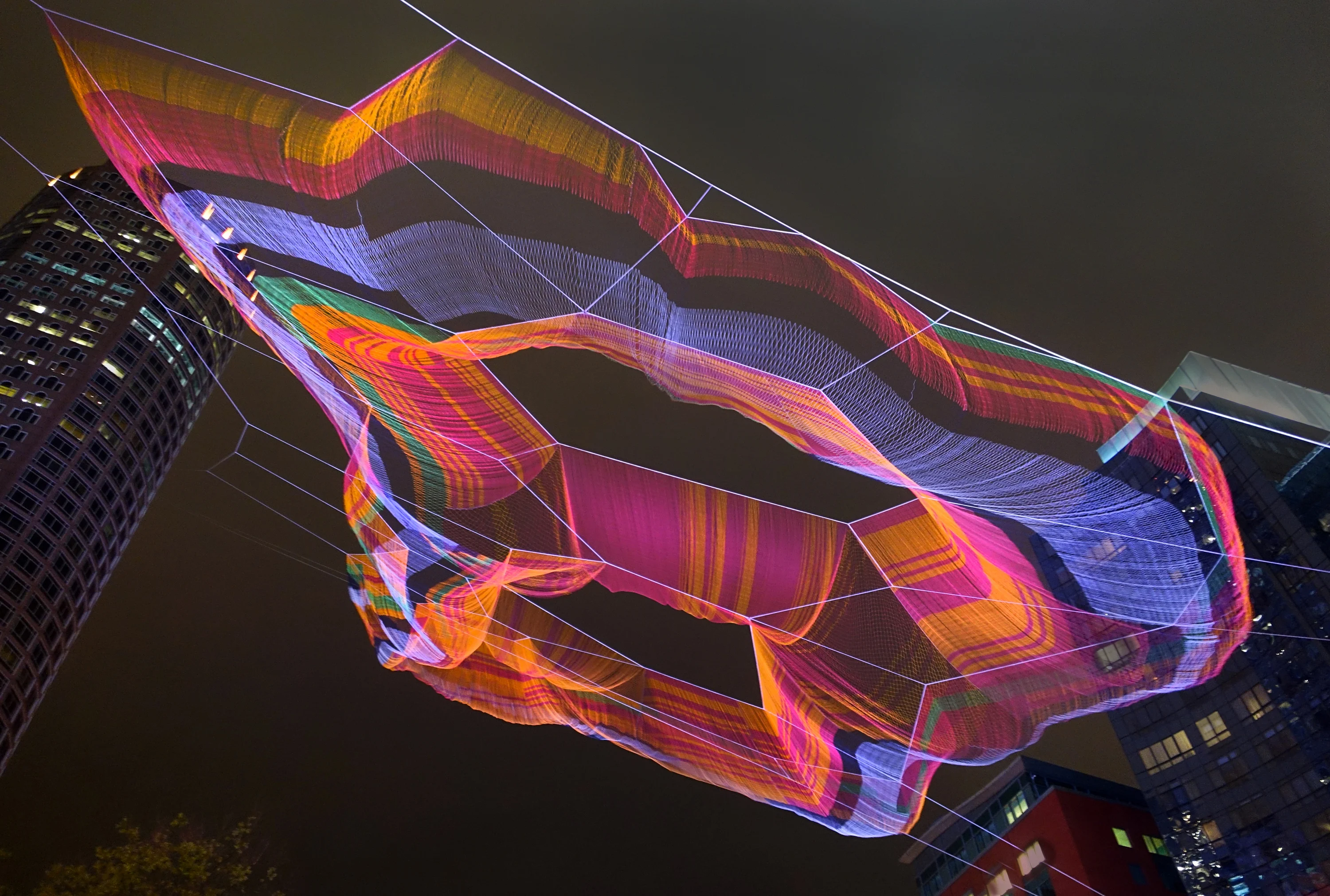

Skies Painted with Unnumbered Sparks was our first project to stretch long distances from pre-existing skyscrapers, which required us to overcome immense practical and technical challenges. At 750 feet, it turned out to be the largest pre-stressed rope structure in the world.

My original goal was to sculpt at the scale of the city, as a soft counterpoint to hard-edged buildings, while attaching exclusively to pre-existing buildings as if the sculpture were literally laced into the fabric of the city. My first big hurdle was that the kind of computer software tools I needed, simply did not exist. Fortunately, Autodesk, a company that builds design tools, believed in my idea, and their engineers dedicated two years to develop the tool.

Another hurdle was convincing tall buildings to let me attach to their roofs. Just hoisting more than a ton of fiber sculpture into the air over an active city and a federal port seemed impossible. It was like a dream; our team worked through the night to gently lift it over bus shelters and trees.

It was terrifying attempting something that had never been done before, and until I saw it floating in the sky, I could not believe it. I remember the first night, swimming on the roof deck pool of the hotel beside it, watching its translucent layers gently moving in the wind. It was one of the most satisfying moments of my life.

What do you hope people will think or feel when they encounter one of your works?

I leave my work open for each person to complete. My hope is that each person becomes aware of their own sensory experience in that moment of discovery, and that may lead to the creation of your own meaning or narrative.

It’s important to me that the work is out in the public realm, often over the streets or walkways. When I installed a sculpture in Sydney, Australia, a man who lived on the street came up pushing a grocery cart. He asked me what the work was and shared with me what he thought. He might never have felt comfortable entering an art museum, but everybody feels entitled to be on the street. It’s like breathing air. I want my work to be as accessible and free as breathing air.