In 2001 the world watched as a band like no other released its first track Clint Eastwood. Gorillaz, the brainchild of musician Damon Albarn and visual artist Jamie Hewlett is made up of four fictional band members with their own peculiar personalities and style, living in an incredibly detailed world. The lively cartoons soon captured, and still do, the imaginations of their many fans.

Joe Zadeh spoke to Jamie on how he goes about drawing the Gorillaz characters, what keeps him interested in the project and how an obsession can turn into hundreds of drawings of pine trees (yes, you read that right).

All images © Jamie Hewlett.

5.15 is a real nice time in the morning. A soft blue twilight time reserved mostly for birds; before humans turn their voices up, emails arise, and iPhones begin to boo-dah-ling. This is when English illustrator Jamie Hewlett likes to get up. He opens his eyes, fingers through the news, and then leaves his apartment in Paris’ 11th arrondissement for his daily walk.

The Promenade Plantée is an elevated walkway – created in 1993 from the remains of an abandoned 19th Century viaduct – that sits ten meters above the streets of Paris. It’s filled with trees, plants, flowers and small square pools and Jamie walks the full 4.7km to the forest at its finish, and then back again.

At around 8.30am he grabs a coffee and a croissant, and then wanders through a secret hole in the wall into his studio (a neighboring bedsit he acquired when the previous tenant wanted to sell).

It’s littered with books, postcards, cuttings, artwork and anything else he’s collected over the years, highlights of which include a New York Police Department helmet, a replica Thompson submachine gun and a monk’s skull. “It all gets drawn at some point,” he smiles.

He likes to have BBC Radio 4 on when he sits down to work, because “when you’re staring at a piece of paper all day long, it’s nice to feel like you’re learning something.” It puts him in the mood to create, ever closer to the moment when the juices begin to flow, when what he’s doing looks like it might just make sense, and his mind is edging ever closer to that place.

“That moment,” he says, “when it’s really happening before your eyes, and everything is just perfect, and all the lines you’ve got on the paper are in the right place. That’s all drawing is really, just putting some lines in the right place. Exactly the right kind of lines, and then lots of color, and you’ll find something amazing.”

At least, this is how his days are supposed to go. “I haven’t been able to do anything decent for about five weeks,” he admits. “I’ve sort of hit a dead end.”

Over the last 25 years, Jamie has become renowned as an award-winning illustrator, artist and music video director, capable of dreaming up entire universes.

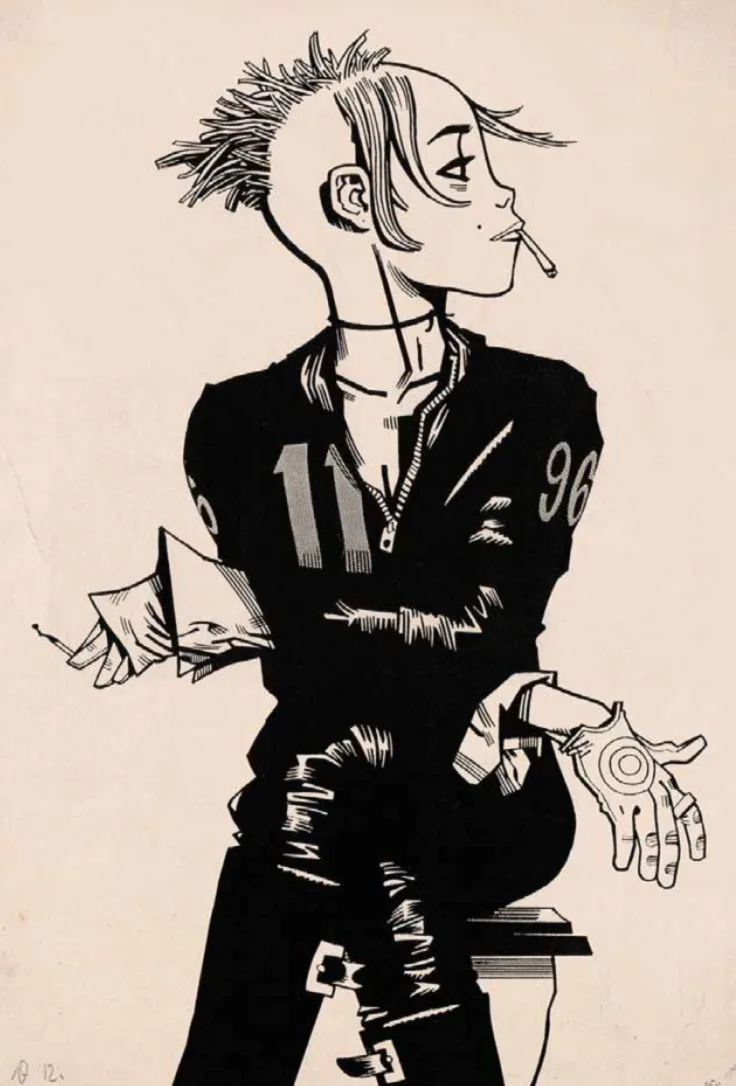

In 1988, aged just 20, he co-created the cult comic series Tank Girl with his friend Alan Martin. Tank Girl was a foul-mouthed, heavy drinking, hard fighting, sexually dominant heroine. Someone who’d genuinely intimidate and frighten men, unlike the pornstar-in-a-cape style of other comic heroines at the time.

She became an icon wherever the comic was sold – inspiring protests against Margaret Thatcher, influencing designers like Vivienne Westwood, and triggering the bad girl fashion craze of the early 1990s.

Tank Girl became a springboard for Jamie’s career, and a decade later, in 1998, he went on to co-create the biggest virtual band in the world: Gorillaz.

Jamie Hewlett and Damon Albarn were born within 11 days of each other in 1968, under the Chinese zodiac of the monkey. 30 years later, they found themselves living together in a flat above a carpet shop in west London during a time of personal upheaval. Both had ended long-term relationships, and wanted to do something new with their lives.

Damon had bought a plasma screen television on which they spent hours watching MTV, staring perplexed into the burning bush of pop culture. Everything seemed so phony, commodified and manufactured, but not even skillfully manufactured.

Their response was their next creation, Gorillaz; a group of two dimensional cartoon characters with cliche band member personalities and preposterous back stories. They would be given the room to grow on their own terms, conducting interviews in character for example.

There are four members – 2-D, Murdoc, Noodle and Russel – because “all the best bands have four people,” Jamie says. “Three is too few and five is too many.

“The idea for 2-D was that he was a kinda cherubic, good-looking front man who isn’t smart but can sing. Murdoc was based on Keith Richards, sort of satanic. Russel was this sort of meta, hip-hop guy who has had suffered through life.

“Noodle was originally caucasian and 20 years old, but we thought that was boring. The idea of having a little girl in the band who plays mean guitar was much more fun. Then we made her Japanese – why not?”

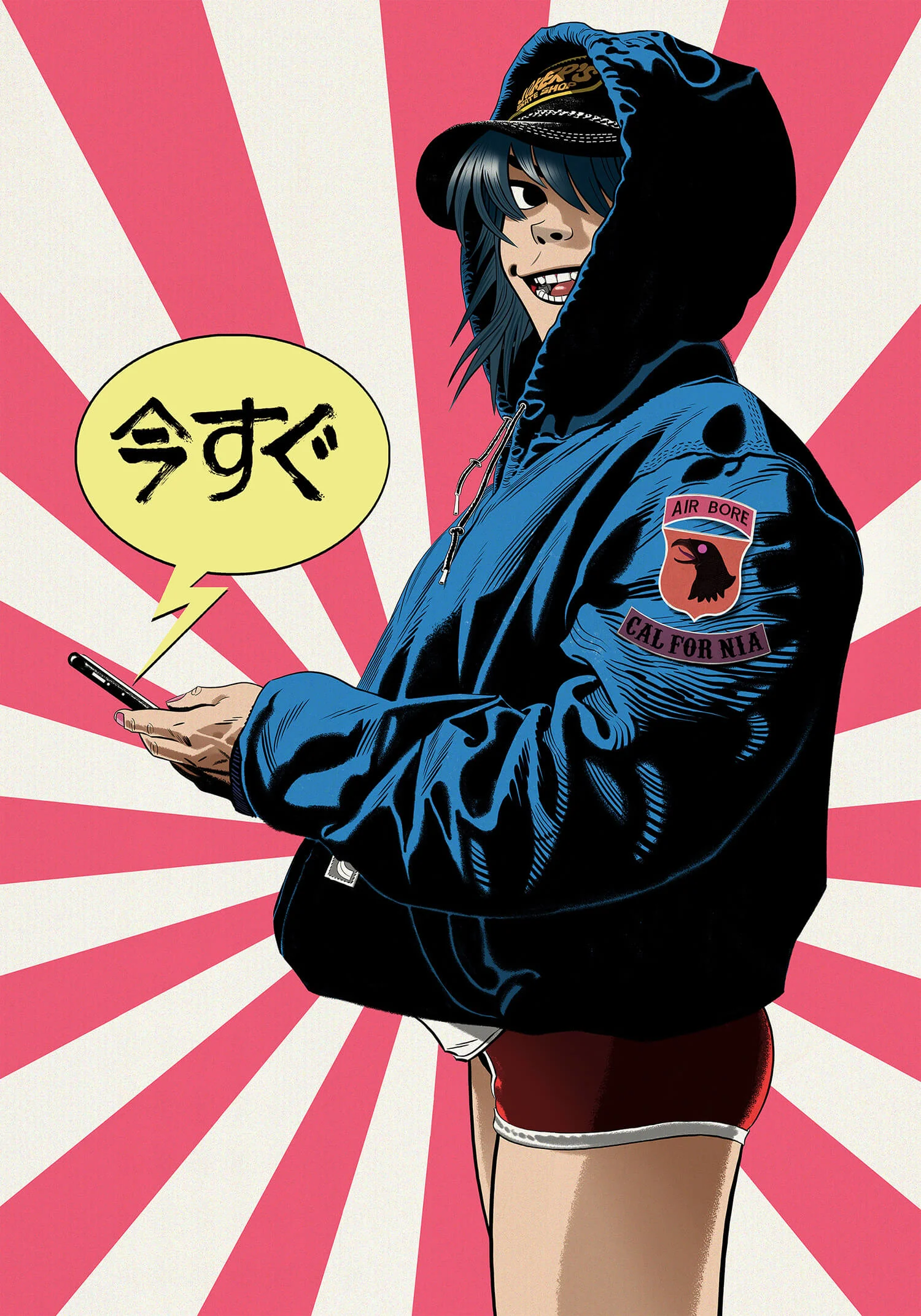

Across the 20 years and six studio albums of Gorillaz, the characters have evolved with their stories. Noodle has grown up and become a woman (“which is something cartoon characters tend not to do,” Jamie says) and 2-D has transformed from a delicate wallflower into an extremely confident adult.

In fact, on their latest record, The Now Now (released in June 2018), 2-D’s confidence has become a problematic arrogance. He has dominated interviews this year, answering questions with fired-up but vague declarations that make no sense under inspection.

“I am able to see into the heart of things,” he said in an interview with Noisey, “like one of those X-rays at the airport where they look at your pants.”

“I guess there’s a lesson in there,” Jamie explains, “which is that sometimes to not believe in yourself is a good thing. Not having too much confidence can keep you grounded, and keep you focused on the most important things, which is your work and your art. That’s what you must focus on, not yourself.

The idea for 2-D was that he was a kinda cherubic, good-looking front man who isn’t smart but can sing.

“That’s why I draw pictures, you know?” he continues. “People look at my pictures and everything I need to say or express is in there somewhere. I couldn’t get on stage every night and do what Damon does, because that’s not me. I’m always impressed when someone can do that – be in the public eye and everyone knows you, but not let your ego take control, because then you lose control.”

To keep the Gorillaz-universe alive, each album starts with a storyline on what the characters will be up to and how they will act.

It usually forms in the same way. While the music is being created, Jamie, Damon and Remi Kabaka Jr. (drummer for the band since 2000) thrash out themes and ideas, talking endlessly about “what we’re into, what we’re not into, what’s going on in the fucking world, what we wanna say, blah blah blah. It’s all quite open and nothing is forced,” Jamie says.

These conversations then inform his first drawings for the campaign, which are go to a team of writers who work on structuring and expanding the story.

Not having too much confidence can keep you grounded, and keep you focused on the most important things, which is your work and your art.

Once an album campaign is underway, Jamie is in a constant state of drawing. New sketches, artworks, storyboards, video ideas, merchandise, tweaking, designing, changing.

In 2017, he helped to envision a virtual reality video for their single Saturnz Barz in which they created a surreal 360 degree haunted house experience for fans to explore. It broke the record for YouTube’s biggest debut of a VR video, being viewed more than three million times in the first 48 hours. Jamie remembers it as a period of “crashed computers” and “scratching of heads.”

“Just doing a video requires a ton of drawings, usually drawings that never get seen because they go straight into animation,” he explains.

As a result, the total body of work he makes for each album is monumental. It’s no surprise that Gorillaz have as rich a legacy in the art world as they do in the music world. Search the visual social network DeviantArt for the word “Gorillaz” and you’ll find 133,120 results of Hewlett-inspired art.

Over the decades, he’s developed working practices that keep him excited about the project. For each album cycle he decides on a brand new illustration style. For example, on their album Humanz he focused on collage, whereas The Now Now has been about black lines and flat color.

He spends the entire album campaign trying to master that style. For most of the duration, this is exhilarating. But as it reaches the final months (Gorillaz have released two back-to-back albums in the last 18 months) he becomes, well, “not tired of it,” he insists, “because I love doing Gorillaz. But that peak of when I’m really in the zone has passed.”

He hates looking at the computer right now. It gives him headaches, and he’s convinced it’s making him go blind. More and more he finds himself craving time away from it. Today he came back from the art store with two big canvases and a load of new paint. He’s about to get started on something entirely new and offline, but he has no idea what.

In 2017 Taschen released a 426-page retrospective of his life’s work – the first ever collection of his art in book form. Flicking through it, you can see the motifs that underpin his style.

A Hewlett-universe is usually a grimy and dystopian place to be, where the only relic of ordinary civilization is the juvenile yet comforting sense of humor that hangs in the air. Monkeys and apes haunt his characters, whether it’s in their bulging noses or protruding mouths. He sees things with a sharp eye, both in the jagged and angular shape of teeth, fingers and joints, but also in the voguish way his characters are dressed.

The attention to detail is almost manic, from the inventive placement of buttons on a jacket to the way socks hang in a certain way around ankles. He is punk and manga all at once, and also, sometimes, neither.

Deep down, he’s a nostalgia junkie. His biggest influence to this day is the 1950s and 60s heyday of the barbed satirical American publication Mad Magazine. He adored the storytelling oil paintings of Norman Rockwell, and he also loved the way Mad Magazine ridiculed the painter.

The day before we spoke, he’d spent an afternoon watching old Daffy Duck cartoons on YouTube. “It still makes me laugh,” Jamie says, “he’s just a selfish little arsehole and I love that.”

People look at my pictures and everything I need to say or express is in there somewhere.

Jamie’s interest in the visual heritage of the past doesn’t mean he’s not open to new experiences. When he first met his wife, the French actress Emma de Caunes, she offered to read his tarot.

“I imagined a scene from a James Bond film, where she turns over the Death card and there’s a clap of thunder,” he laughs, “but it’s not like that.” Now, whenever he has a problem, he gets her to read his tarot.

One day, he came across The Way of Tarot, a book written by the mystical avant-garde filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky . Inspired by Jodorowsky’s study of the legendary Tarot de Marseille deck, Jamie decided to create his own version of the deck’s 22 major arcana cards.

“I thought I’d like to redraw them based on exactly everything that researched,” he says. “It became a little obsession. I didn’t work on the computer, I hand-painted them on card in watercolor, gouache and India ink. It took forever because when you make a mistake in that medium, you have to start again. It took me three years to complete them.”

Jamie’s take on tarot is dreamy and absurd. He’s leaned into the mysticism of the form – on The Chariot card the horses look charged with a divine electricity and The Pope has something of the inter-galactic overlord about him. But his wit still rises to the surface; The Lovers are engaged in a rather disinterested and half-hearted grope, and The Fool is having his bum felt by a monkey.

When Jamie goes for his morning coffee and croissant, he sometimes sees Jodorowsky in the same cafe. The 89-year-old director lives in the area. Sometimes he even gives free tarot readings to strangers. At a party, Jamie bumped into the director’s daughter. “You should show him your tarot work,” she said. “I’m sure he’d love it.”

Jamie hasn’t shown Jodorowsky though, and probably never will. “I tend to find it’s better not to meet the people you admire and just keep it like that. I find it quite tiring meeting people. I just want to be left alone to do my drawing.

“When I’m not drawing, I’m thinking about my drawings. If I’m doing a drawing and it’s not going well, and I have to stop to go and do something, then I’m just thinking the whole time about the drawing and how I can fix it. Whatever place I need to be, or people I need to see, I just want it to finish so I can get home and work on the drawing. I’m obsessed by it. I dream about it.”

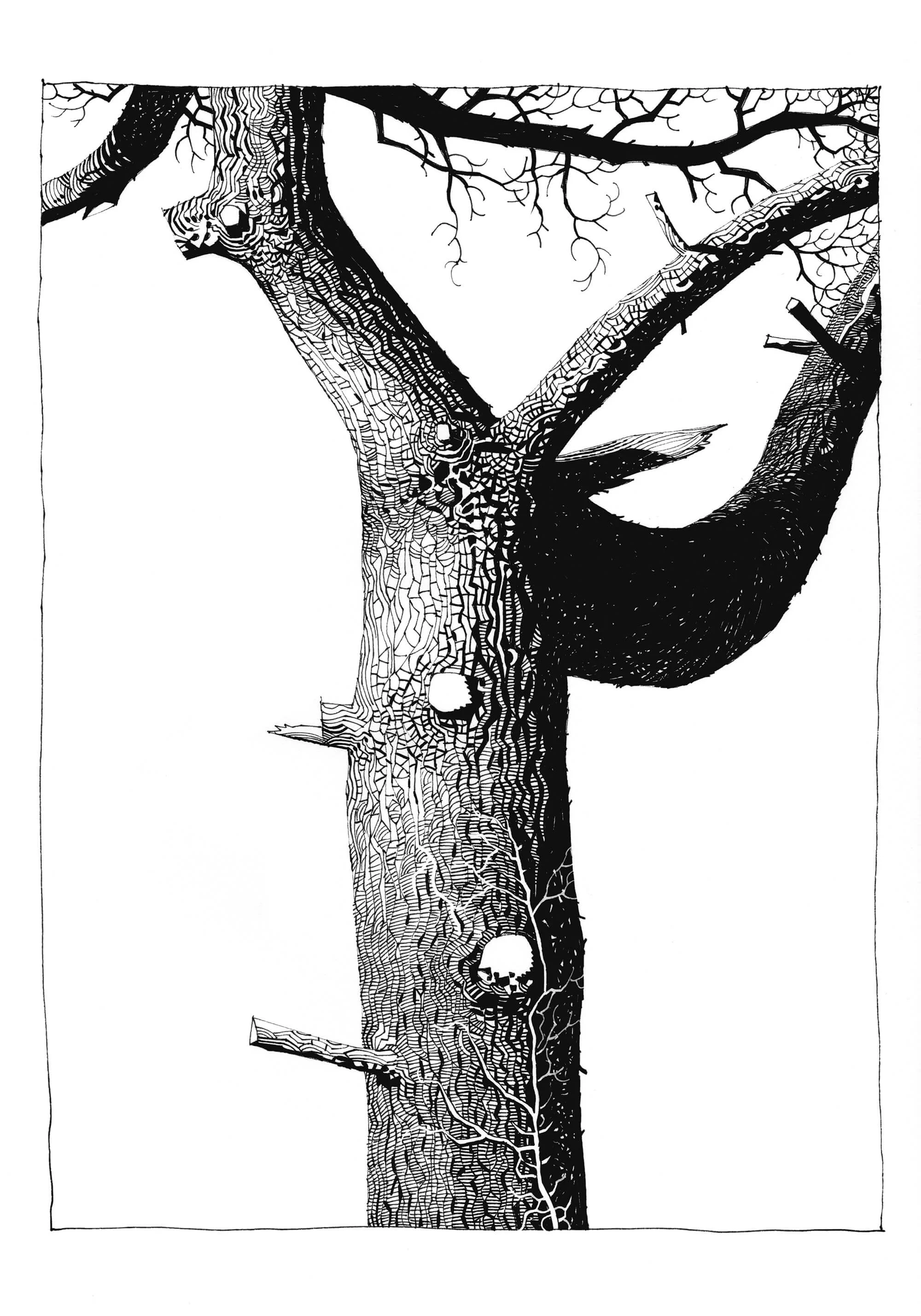

An obsession like this can take hold in unexpected ways, snared by unexpected things. On a trip to the west coast of France for example, Jamie became captivated by the pine trees outside the holiday home and the way they’d been deformed by the winds sweeping in from the North Atlantic.

One evening, when the sun was low and the trees were casting shadows all over themselves, he sat down to draw them (he always takes a black felt-tip pen and notepad on holiday). It felt good. So, he got on his bicycle and cycled the entire peninsula finding other pine trees to draw.

When I’m not drawing, I’m thinking about my drawings.

“One pine tree looked like two people fucking,” he says. “Another looked like it was trying to have a fight with the pine tree next to it. It’s like they were all telling a story. I imagined that they were actually moving, but so slowly that we would never be able to see it with the naked eye. You would have to record them for ten years to see what kind of pantomime or play they were performing with each other.”

Like Claude Monet, who painted only haystacks for almost four years, Jamie drew only pine trees for months and months. This is the kind of work he most enjoys; work done for no other reason than the fact he wanted to do it. Drawing and drawing and drawing pine trees.

It was mad and brilliant, something he felt he just had to get out of him. At night, he began to dream about the texture of bark. Then one day, as BBC Radio 4 played in the background, he put his pen down and decided, “That’s it, I’m not going to draw another pine tree.” It was done.

Jamie’s pines are stark and evocative. Staring at them takes you to an enchanted place. There’s a Brothers Grimm-style fairytale darkness to them, like the kind of trees Hansel and Gretel would gaze at on their way to the cannibalistic witch, unaware of what awaited them.

They are as much a study of light as they are of trees, and how a tree can look so different depending on whether it’s bathed in sunshine or cloaked in darkness.

Jamie has one of the pine tree drawings in his bedroom at home. It was one that his wife particularly liked, so they framed it and put it on the wall. Some mornings, they find themselves lying in bed with a coffee staring at the artwork. Even now, they swear they can see things they’d never noticed before, lurking in the shadows or the shapes within the bark. Details that hide beneath. Pictures within pictures within pictures.