Growing up in the 1960s, Glen Baxter was a child with a passion for the surreal, a love for cinema and a stammer. Decades later his sought-after work is rooted in the ability language has to mislead us, confuse us, and make us smile. A combination of words and pictures which invite you to step out of the ordinary, just for a minute. Liv Siddall meets him to talk about lesser-used verbs, the poetry scene in 1970s New York, and finding inspiration in overheard conversations.

When you’re a kid, humor can be found everywhere: cartoons, films, your friends, comic books, the back seat of the bus, in clandestine notes in class, the backs of cereal boxes, giggles after lights out at a sleepover, even just plain old question/answer jokes can make you double over. Doesn’t tend to stick around, though. The swamp of puberty and the cog-like onslaught of age naturally decreases life’s funniness. If you can retain an ability to find humor in things, to be able to get the giggles, or crack yourself up, or put a funny spin on an otherwise bland or tragic situation, then you are in possession of a valuable, coveted tool that will see you through the difficult – or just boring – times of life.

Glen Baxter is in possession of this tool. I’d known about his work for a few years until I started being one of those people who crosses over from admirer to fan and starts searching for and buying essentially useless merchandise from other Glen Baxter nerds online. I was consumed by the idea that his work was one of the only – or maybe the only – species of artwork that could really make me laugh out loud. Considering the gargantuan breadth and endless output of the publishing, art and content galaxies, you would have thought that more of it would be amusing. But the online and offline art world can sometimes lean towards seriousness over impishness. A place to show off about how grown up you are, rather than celebrate how immature you feel.

Glen has dedicated his life to the surreal. He doesn’t want to be – or is not interested in being – thought of as being someone that tries to make people laugh, as it would cheapen the craft of what he does. He’s an artist, not a comedian or cartoonist. The things that interest or inspire him, which come out in his paintings, just so happen to be funny.

When I was a kid and I saw things I couldn’t understand, I was fascinated by that and I still am.

A few days before the UK’s lockdown rules came into full force, I walked through quiet streets of south London, to a house on a blossom-covered street in Camberwell. I rang the doorbell – one of those long, ornate old fashioned ones – and heard it chime within. No one came. I rang again. I sat on the doorstep for a while wondering what to do.

Just then, the heavy door swung open and Glen Baxter barged towards me without noticing I was there and nearly knocked me over with two large bin bags. “Oh, hello!” He said, surprised. He accused me of not having rung the bell. I said I did, twice. He asked me to do it again to prove it.

Glen’s supposed to be 76, but you wouldn’t know it. What I learned from reading a lot about him in the last year or so is that most of what you read online isn’t actually true. Not just incorrect, but purposefully misleading. Sometimes you’ll find entire articles about Glen which turn out to be fictional, written by fans who want to ape his penchant for the surreal. I looked at the acknowledgements and introductions in as many books of his that I could get my hands on. Most of those are written about Glen by someone with a funny name. I assume they’re written by Glen himself, but when you ask him he just smiles and shrugs.

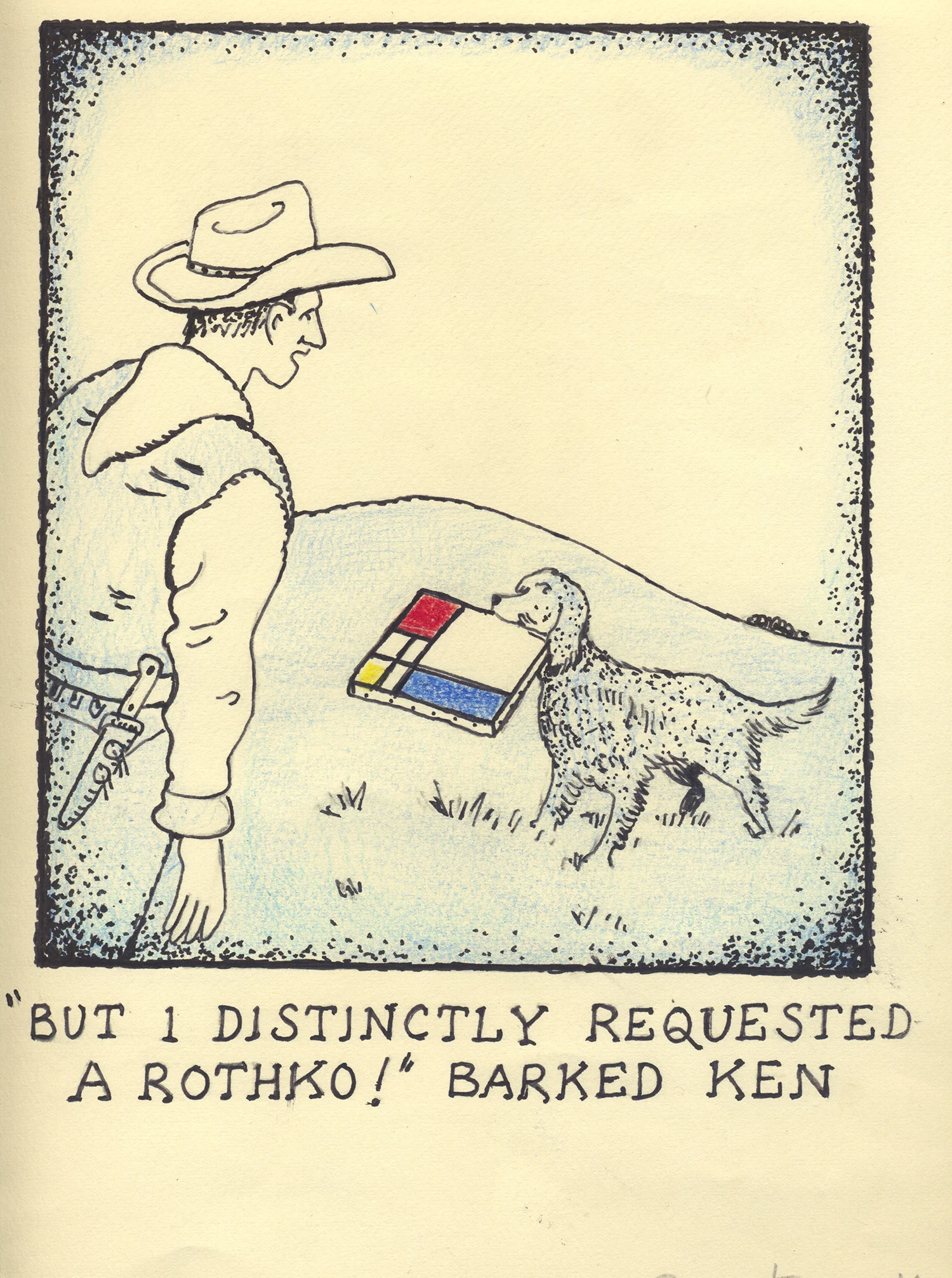

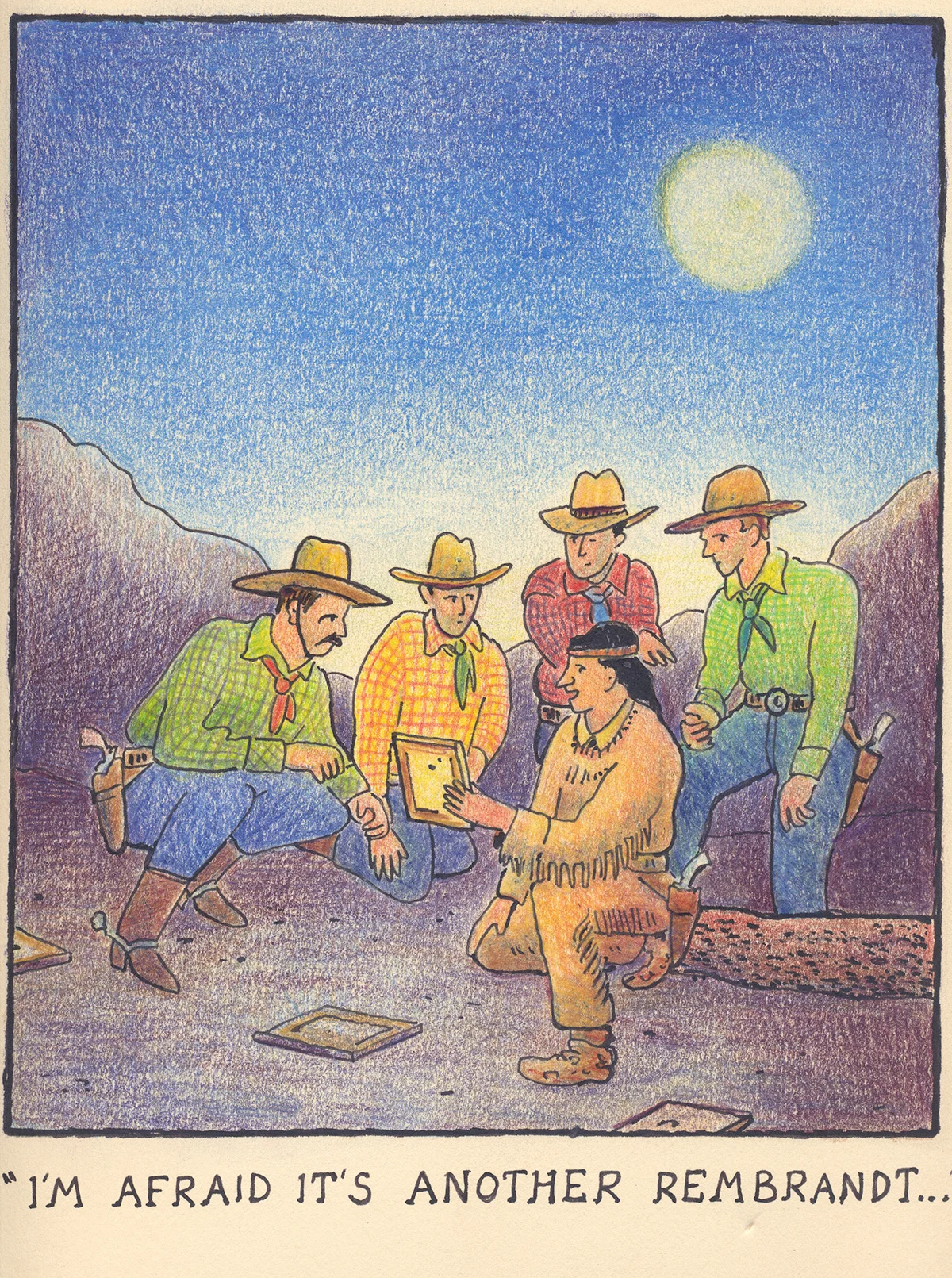

Glen was born in Leeds in 1944 and spent his childhood hopping between the cinema and the library. The former for the exotic, American allure of Westerns and the slapstick Marx Brothers, and the latter for a supply of Biggles books. Biggles was a series of adventure books for children by W. E. Johns centered around the life of a pilot, James Bigglesworth. While the slapstick of the Marx Brothers lit a spark in Glen that would never flicker, it was the vocabulary of Biggles that got him interested in words. “On the back of the book, the author – who’s called Captain Dibbleby Johns – would write this letter to the readers and sign it, ‘yours aeronautically’ and I thought ‘that’s class, this,’” Glen recalls. The fact that there wasn’t even a rank of captain in the RAF (making Biggles totally bogus) tickled him, as did the preposterously long words used in a book for such young kids to read. “He used words like ‘reconnaissance’ and didn’t speak, they ‘opined,’ or they ‘blurted,’” he explains. “Nobody ever ‘says’ anything in my drawings. They blurt or they squeak, or they whine, you know?”

Glen went to fetch a Biggles book not from the attic or in an old box somewhere, but from an easily-reachable collection of them in the bookcase in his living room. I flicked to a random page and started reading. “The sky was illuminated by a phosphorescent glow, it was not constant, it waxed and waned like the reflection of a colossal blast furnace...it was a cold vivid electric blue, for some seconds they watched it in silence, all subdued by the unearthly manifestation.” It’s hilariously wordy considering it’s a book for young children. The absolute antithesis of Peppa Pig.

What more do you need to pack to take to art school than a knowledge of adventure cartoons from a bogus pilot, a head full of Marx Brothers gags, a hatred for P.E and a particularly bad stammer? Glen arrived at Leeds College of Art with all of it. Art school sat maybe even less well with Glen than actual school did. Out of the frying pan and into...art school. “It was terrible,” he says, smiling. “They were all painting these abstract pictures – big blocks of blue and purple – I thought ‘hang on! This isn’t what I want to do!’ I started stuff and I’d get told off. ‘Don’t be silly,’ you know.”

To a certain type of art student, “don’t be silly” could be as useful a command as saying “stop laughing” to a person already in hysterics. It didn’t stop him. Poetry appealed to him and he wrote and painted his way through art school before graduating and moving to Leytonstone in north London, purely because it was where Alfred Hitchcock was born. He took a job in a local junior school as a football and pottery teacher (“It had never been done before, not together, you know,”) in his spare time would hang around famed independent bookstore and counterculture hub Better Books on the Charing Cross Road. It was there, surrounded by like-minded people, that his interest in the surreal and the written word was reignited, or verified. He found his people. “It was the place to be,” Glen recalls. “I started working with an alternative theatre group called The People Show, I wrote a couple of scripts for them and actually appeared in one in an Edinburgh Festival in 1968, I appeared on stage as Inspector Baxter. It was good fun yeah. I’d never been to a festival and I’d never been on stage.”

Glen moved to teach at a different school in Islington in 1970 where he met his now-wife Carole, also a teacher. Carole encouraged Glen to keep writing and painting. They moved to Camberwell together, to the house they share now, when Glen started teaching two days a week at Goldsmiths, spending the rest of his time writing and painting. She came in to say hello during our interview, telling us about how someone had found a dead body in a skip behind their house recently. “What was put in a skip?” I asked. “It was the last person who interviewed me,” Glen chimed in, deadpan. “Spooky or what?”

You probably couldn’t name more than a couple of poetry magazines now, but back then, around the time Carole met Glen, in the boom of publishing, poetry and literary magazines were huge. They spread over the world like dispersed, wind-blown seeds. Glen’s poems were picked up and published in one called Adventures in Poetry, made by a poet called Larry Fagin in New York, who – as well as sharing Glen’s penchant for children’s adventure books, hence the name of his magazine – commissioned, wrote and printed the magazine from The Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church, which opened in 1966 and is still going today.

It’s like you’ve found a missing page from a book, but you don’t know what the book is.

Larry loved Glen and his poems so much that he invited him to read them out in St Mark’s Church. “It’s a very famous venue where William Burroughs and John Cage had performed,” says Glen. To a young writer, turning up in the East Village at the height of the slam poetry scene in New York in the early ‘70s would be like an artist stepping inside Warhol’s Factory. Glen said New York felt like “putting your finger into an electric socket” and that it was “a whirlpool of energy...the art scene was so vibrant. Everyone seemed to be a poet, or aspiring to be a poet.” These were the days when artists and poets lived in warehouses all over the city, paying next to nothing in rent. New York was grimey, electric, riddled with crime. Glen stayed bang in the middle of Greenwich Village, in a house owned by popular humorous poet and connector Kenward Elmslie.

It’s easy to romanticize New York in the early ‘70s. I do it all the time. I like to imagine sitting outside a cafe wearing dark sunglasses and watching Patti Smith walk by deep in conversation with Robert Mapplethorpe, or Iggy Pop strolling along with Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground. But it was like that. Imagine an entire area of a city united by a near-decade long passion for words, art and music? Imagine being Glen and going from Leeds, to Leyton, to Camberwell, then suddenly being enveloped in this crazy, culture-defining heart of the artistic world in a time where anything was possible, and people wanted to hear, or see, or watch what you had to offer.

Spending that much time with people for whom words were everything made a mark on Glen. People (well, not Kenward who is probably the only millionaire poet to ever have existed) were happy to have no food and no money in order to spend their days writing poems and creating communities and small publications. Glen performed on-stage in full tweed at The Poetry Project and brought the house down. Later, he’d get on a Greyhound Bus to poet Clark Coolidge’s house in Massachusetts. He’d later collaborate with Clark on a book called Speech with Humans. “It changed everything for me,” says Glen, “I saw a side to the world I had never experienced before.”

In 1978 Glen was back in London, creating poetry and drawings which had, by then, begun to symbiotically morph into one. “The first poems I used to write somehow became condensed, a bit like captions under the pictures,” he explains. “It works because it’s like a fractured narrative. It’s like you’ve found a missing page from a book, but you don’t know what the book is, and it’s like; ‘why is that happening there?’ It’s that collision, that moment of that little explosion of thought.”

Glen’s new-found format – a wonderfully simple cartoon-like template of image up top, one-liner caption beneath – caught the attention of a Dutch publisher, Jaco Groot, who he became firm friends with and still works (and holidays) with today. Jaco and his wife are the founders of De Harmonie, a publisher in Amsterdam. He’d seen Glen’s work in a little poetry magazine called The London Review and tracked him down. Glen went over to Amsterdam with a suitcase of drawings which, with Jaco’s help, went on to become his first book: Atlas, in 1979, printed in black and white because color was too expensive. “I thought to myself: ‘this is it now, this is great!” Glen recalls, laughing. “Jaco sent his reps round the whole of Holland with this book and he got orders back for six copies...Another get rich quick scheme was faltering.”

It didn’t matter though. Later that same year Glen was offered the chance to exhibit some of his work in the Corridor Gallery of the ICA, in a slightly unglamorous but perfectly placed location: right between the bar and the toilet. His work was subject to rave reviews in the Times and the Guardian and Glen was suddenly overwhelmed with attention from competing publishers. For the next few years he churned out work: walking away from teaching and living in London as a full-time artist. In the late ‘80s he began accepting editorial commissions and taking full advantage of the joys of the newly-invented fax machine. “You’d fax your drawings into the New Yorker, and then you’d go to bed and the next morning there’d be all this, just rolls of paper just spilling out of your machine, it was great. I loved it! I could send a drawing to Jaco in Amsterdam and I’d know that he’d be getting it as I was sending it.”

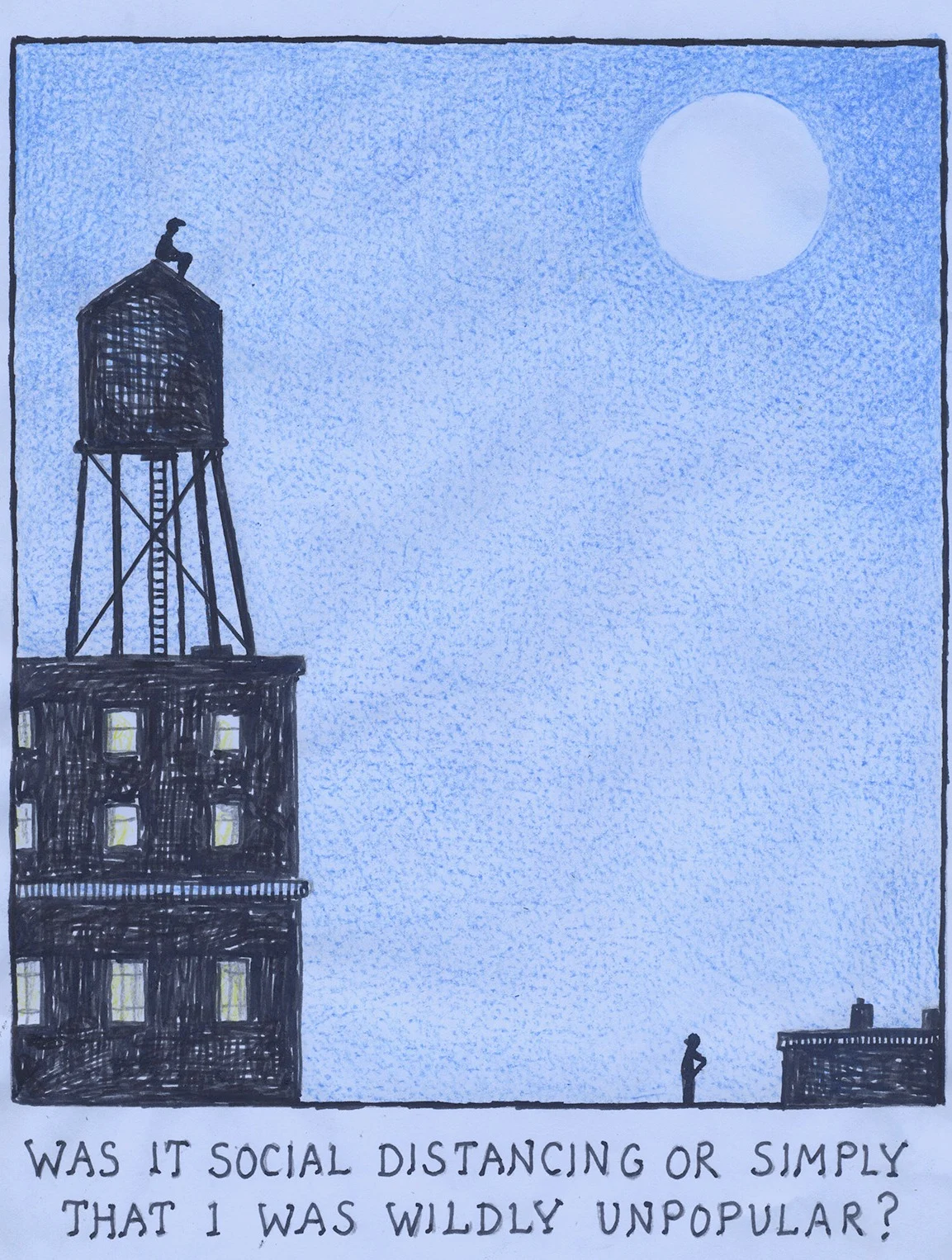

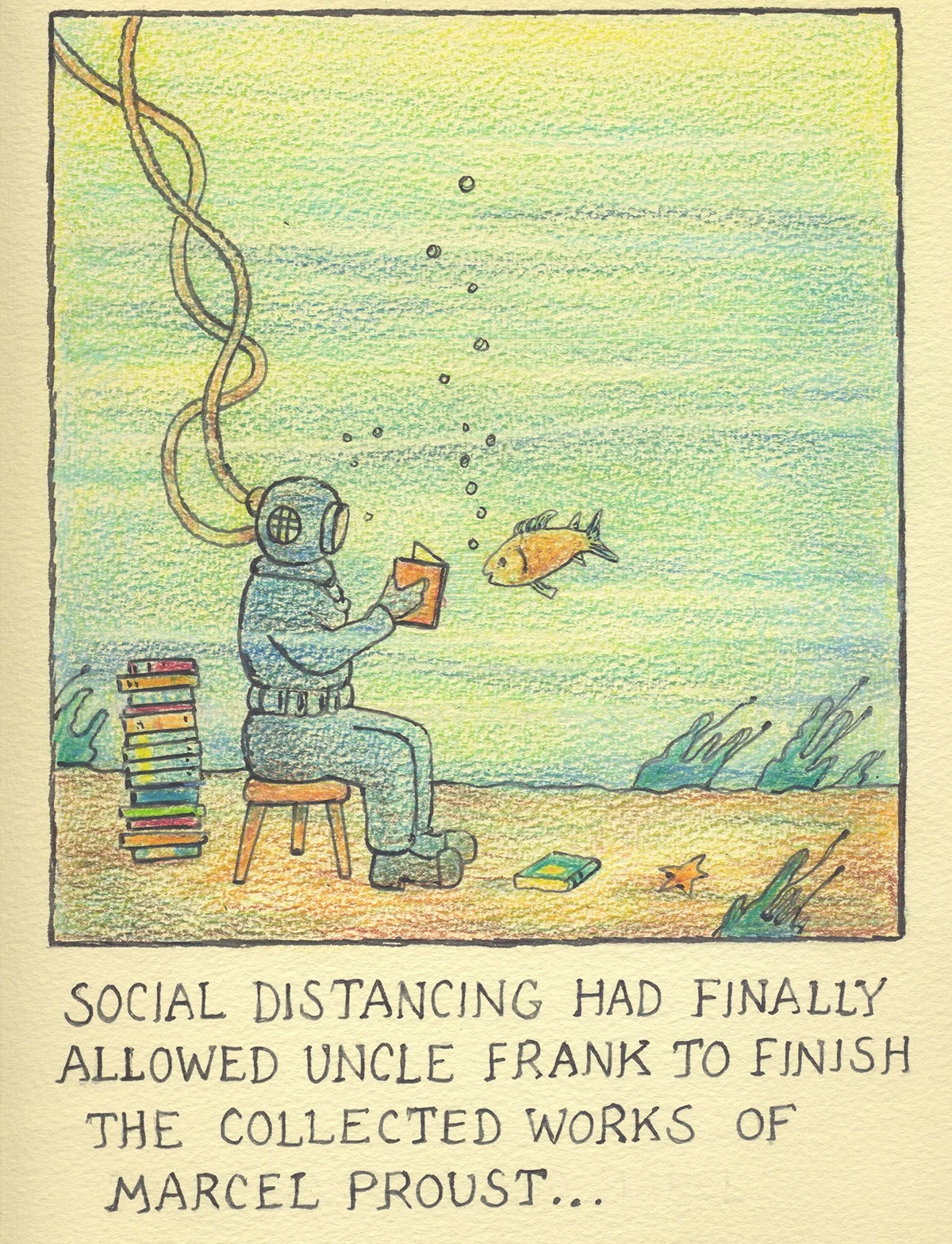

These days, Glen’s still creating editorial work sometimes (most recently a cartoon for The New Yorker illustrating life in lockdown) but is still a full-time artist, creating large-scale paintings in his little home studio which is filled with piles of country music CDs and loose drawings. Sometimes he’ll wear a Stetson while he works to get in the mood. Some days he’ll be working on personal commissions from fans and at other times he’ll be working on a series for a show. I mentioned before how, when researching Glen, you’ll come across book introductions, interviews and articles which can, in most cases, end up being written by Glen under a pseudonym. Like he’s leaving a breadcrumb trail around for dunces like me to follow only to be met with dead ends and confusion. Once, when his editors at the New York Review of Books asked him to find a famous person to write an introduction to one of his new books, Glen was so embarrassed at the idea he wrote it himself, under the name of “Marlin Calestine from Toledo, Ohio.” In the same book, under a subheading “New and forthcoming titles from New York Review of Comic Books” are a list of books that could well be real, but just have a whiff of something amiss. “Pretending is Lying by Dominique Goblet,” I say to Glen. “Is that you?” “No...” he says, deadpan.

It’s that collision, that moment of that little explosion of thought.

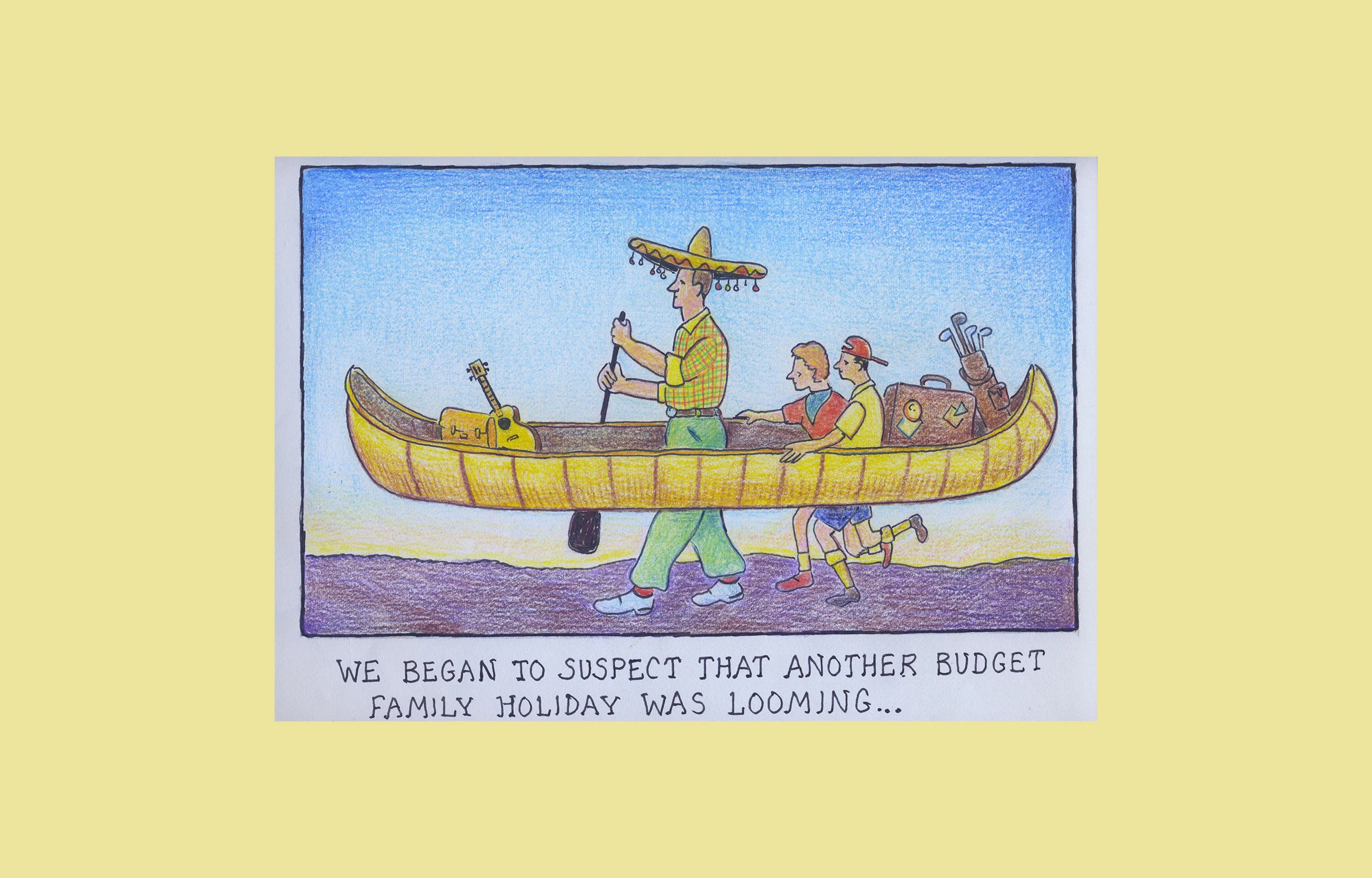

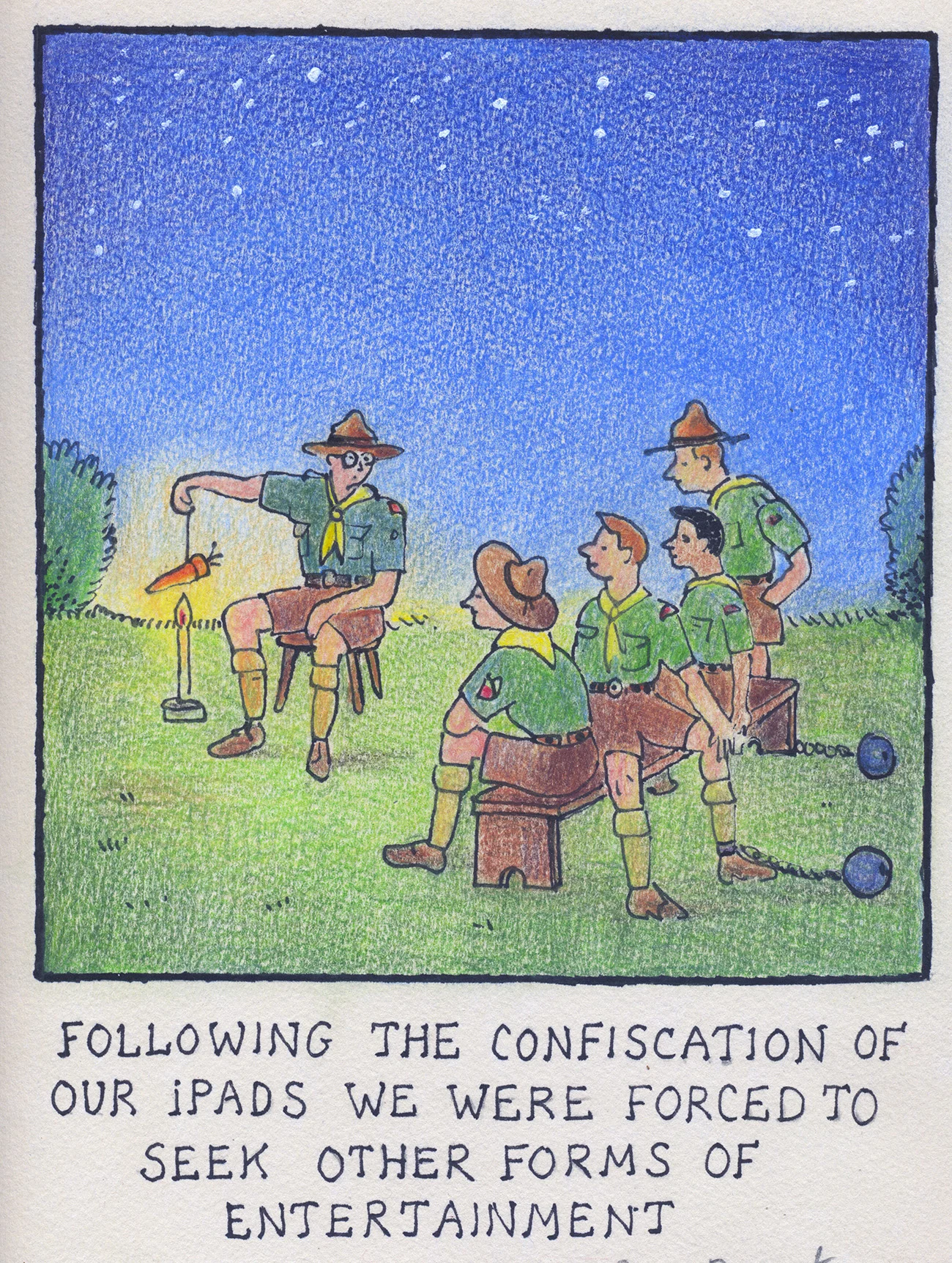

Confusing us, forcing us to question our relationship with words, pictures, or even the format of books, makes him happy. Since Glen was a kid, he’s been fascinated by things that he couldn’t understand. “When I was a kid when I saw things I couldn’t understand, I was fascinated by that and I still am,” he says. “I want people to look at my work and go ‘what’s funny about this?’ You either get it or you don’t.” He likes the moment in which our brains have to suddenly work slightly harder to process something in front of us. His images offer us an image of something recognisable, then pulls the rug from underneath us with an entirely unrelated caption below it.

The magic thing is that the combination he creates actually works. It’s the artistic equivalent of gherkins dipped in peanut butter. His drawing style lures us in quickly: clear line drawings of safe-looking adults and adventurous children, coloured in with pencils, visual reminders of the books we read when we were kids. The caption beneath can be digested and understood by anyone with a grasp of the English language regardless of age or background. His works are accessible without being overly simple. The humor present in them is not snarky, or sarcastic, or dark, it’s warm. Giggle-inducing. Importantly, it reminds us that life doesn’t always have to make sense. Not everything is as it seems.

“What I hope happens is that opens a door for somebody or gives people licence to do something: to be creative and find something different and go on a different course,” says Glen. “Like that thing that kids have, they’re so creative and then it’s all hammered out of them at school and they stop writing poetry and they’re told how to do adverbial clauses and it just stifles them. They all have this magic, you know.”

Glen’s work rarely changed in style over decades, his paintings now are almost indistinguishable from the works he was creating in the 1970s. Themes emerge every now and again when he becomes slightly obsessed with something (cowboys, for example). Sometimes it can be words like “blurted” which you’ll see popping up more than others. Ideas for his works will come to him sporadically, from overheard conversations, slightly abstract moments, or glitch-in-the-matrix happenstances. Like the time he met a real cowboy on a trip to America who told him he had once visited London and “been through the Tate Gallery.” “I thought of this image of a cowboy riding through the Tate gallery, and I used it in one of my pictures,” says Glen. Sometimes he’ll just mis-hear something someone says. “It’s gold dust,” he says.

“Overheard conversations mainly, and also certain words. I try to smuggle words into a sentence that I really like. I’ve used a lot of ‘snoods’ and ‘wimples.’ I’ve just had an exhibition in London and the title was ‘unflinchingly gamboge.’ Together those words create a little explosion, you know, of mystery and humor. It’s perfect.” I asked him if he ever gets frustrated at how unadventurous we can be with our vocabularies. “That’s my mission in life,” he says, laughing. “I’m trying to bring these words into general usage. Also, as an ex-stammerer, you’re kind of like reclaiming these words and getting power out of them. Revenge of the stammerer!”