You may not think you know who Eiko Ishioka is, but if you’re into film it’s likely you will know her work. The late Japanese designer created jaw-dropping, extraordinarily detailed, fantastical costumes for cult movies such as “The Fall” and “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” among others. She was also responsible for making one of the most groundbreaking and heart-stoppingly beautiful ad campaigns of all time involving Faye Dunaway eating a boiled egg. So, who was Ishioka? Writer and artist Charlie Fox investigates the back catalog and early life of one of his most treasured heroines.

Eiko Ishioka’s work makes my brain explode.

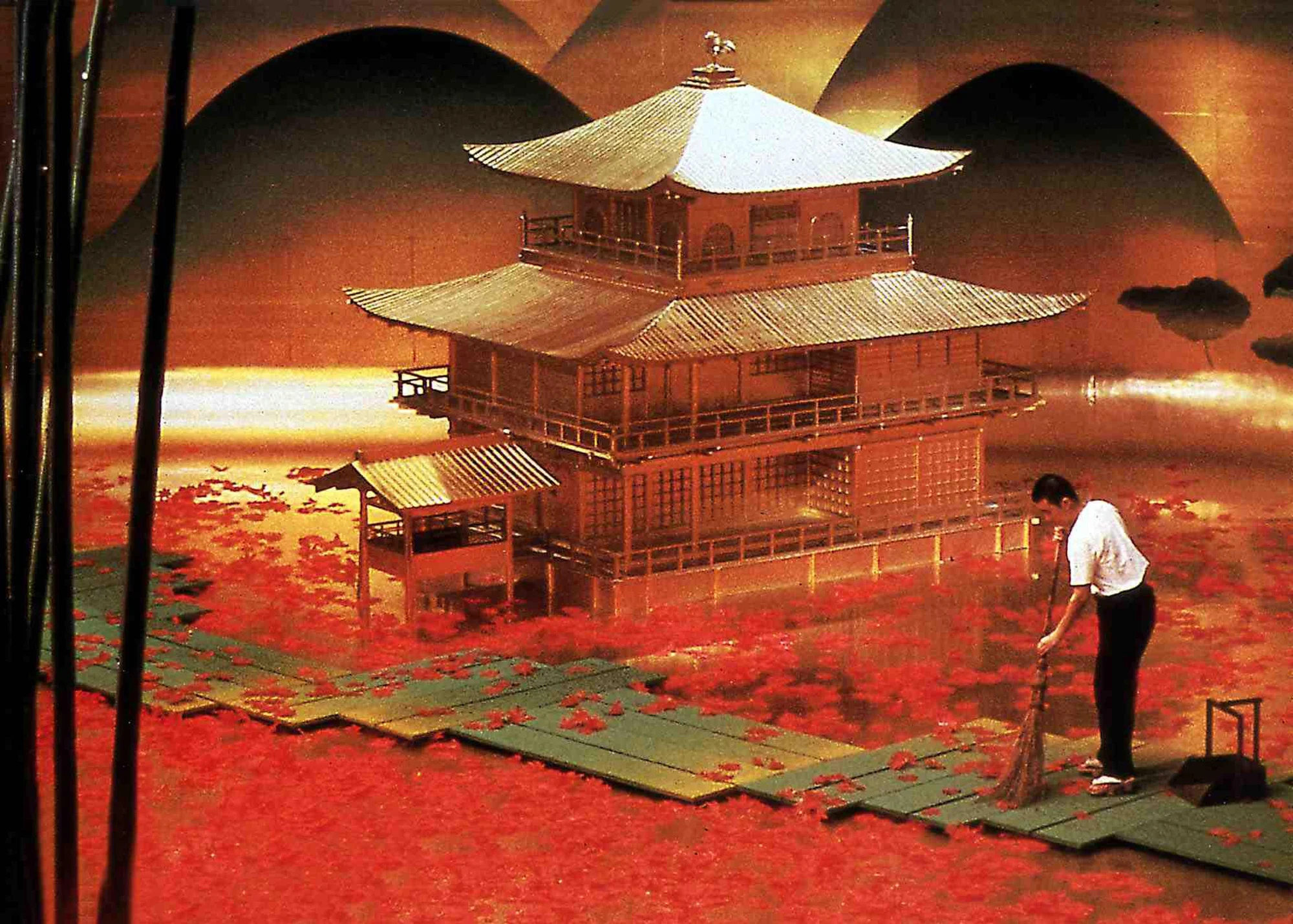

Nobody before or since has created anything as weird and singular as the album sleeves, exhibition posters, and advertising campaigns that she created during her huge and chameleonic career. Probably her best-known and greatest work was created during her stint as a costume designer in Hollywood. She opted just to call herself a “designer,” a term which is pretty amorphous but still doesn’t capture the sheer brain-melting imaginative flair of somebody who decided to dress up Jennifer Lopez like a cyberpunk sphinx for the journey-into-the-mind-of-a-serial-killer epic “The Cell”(2000); who directed the video for Björk’s goosebump-inducing sex song “Cocoon” (2001), in which the singer appears as a ghoulish nude sculpture and gets shrouded by skeins of blood-red cable drooling from her mouth and nipples; who created the trippy theatrical sets for the film “Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters” (1985), a shape-shifting portrait of the tortured Japanese writer Yukio Mishima and his fictional worlds, which is one of the strangest and most beautiful movies ever. Ishioka was also behind the lush-as-fuck costumes for the masterpiece “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” (directed by Francis Ford Coppola) and won an Oscar for them in 1992. Everything she created between her 1960s youth and her death in 2012 is kind of magical.

Born in 1938, Ishioka was the product of a matrix of unique and intense influences. Her father was also a designer; she lived with her parents in cosmopolitan uptown Tokyo. As she explained in an epic 1984 interview with Artforum, “[Our] lifestyle wasn’t a traditional Japanese one. We lived in a Western-style house [...] the two of them took me to French restaurants, we saw American movies […]” (This amazing and epic Artforum interview is by far the most expansive chat Ishioka had with anybody in print about her biography and her aesthetics—it’s like a 19th-century novel or something. So, out of necessity, and also because it rules, pretty much all my Ishioka quotes come from there.)

Then, when she was five or six, World War II hit Japan, which, naturally, caused an earthquake in her brain. Suddenly, the family was hiding out in the countryside. To young Eiko, it felt like they had crash-landed in another century. Traditional Japanese values reigned; all that fun Western stuff she knew was gone. “Everything changed,” she told Artforum. “I was one very strange kid wearing fashionable-looking clothes among country kids who wore traditional Japanese kids’ kimonos. […] I would walk home [from school] alone, but on the way the country kids would kick and punch me. I was very, very lonely.” Not that this hideous experience made Ishioka rebrand as a meek and anonymous mouse. She was defiant and determined. Later, she got revenge for all that trauma through the work: it stands out like something on fire; it doesn’t even try to be “normal” but creates its own luxuriously alien world and dares you to come inside.

The animal inside comes outside; danger and delight entwine.

The whole dislocating experience would replay when she and her family returned to a very different Tokyo in 1945. Occupied by Allied forces, the capital that used to be home had turned into a looking-glass version of an American city. There was a whole new, trippy cornucopia of stuff to taste and touch. Pre-teen Ishioka was bewitched by the influx of American chocolates (“the taste of heaven,” she said), cartoons, packaging, all of it “very, very strange for kids.” Years later, she still claimed that her “first strong impression of beauty” came from American products. “The first film I ever saw was a Hollywood animation,” she recalled in that Artforum interview. “I was shocked, what I saw was so beautiful.” All the key ingredients of her work are here: the unfathomable but ultra-seductive, the supernatural promise of certain objects and textures, the dreamy juxtaposition of Eastern and Western influences, unsettling feelings.

Once Ishioka completed her studies at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music in the early 1960s, she couldn’t be stopped. She was one of those wunderkinds who was greeted with a chorus of “Whoa!” right from the beginning. She could conjure up stark but mesmerizing images at the drop of a witch’s hat. She did a campaign for Japanese skincare brand Shiseido while she was still in her twenties (a girl dreaming on the weirdly fleshy shore of a beach: surrealism gone sunbathing). Her 1979 campaign as art director for Parco, a chain of Japanese shopping malls, starred the actress Faye Dunaway dressed in black slyly eating an egg, her come-hither face wreathed in a funeral veil: the classic Ishioka riddle. She explained that sucker-punching everybody with an incredible non sequitur was a practical necessity on Tokyo streets swamped with rival ads. “My context is junk,” she said, “my competition is tough. My wish is that busy passersby stop, even if for just a second. [...] I have to think about how to get them to stop.”

Her client list got legendary—Issey Miyake, Akira Kurosawa, Isamu Noguchi: serious masters operating in wildly different fields. She concocted the posters for the Japanese release of Francis Ford Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now” in 1979 and her reputation reached Hollywood. Eiko by Eiko, the swanky coffee-table book collecting some of her greatest hits, became a hip touchstone. Ishioka acknowledged that this was a bizarre situation for a designer. “My work is anonymous,” she told Artforum, but now the traditional power dynamics of the artist-client relationship went head-over-heels because Ishioka was being hired to majorly imprint her aesthetics upon a project, transmogrifying the whole thing by virtue of her presence rather than simply serving somebody else’s vision. She became the ultimate person whose services to procure if you were a director trying to represent fairytale spaces, anything deranged or phantasmagorical, mindscapes. As Coppola declared in a documentary on the costumes in “Dracula,” the fact that Ishioka, “a weirdo outsider with no roots in the business” guaranteed that the movie wouldn’t be just yet another zombie rerun of a classic, all flimsy castles and Alsatians spray-painted grey to look like wolves.

I asked my pal, the artist Matt Copson, a fellow Ishioka fiend who once WhatsApped me in the middle of the night re: the biopic “Mishima,” “HAVE YOU SEEN THIS?!”, to explain her power. He told me, “I love how operatically she treats archetypal characters—from Spider-Man to Mishima to Dracula—like they are toys to be played with and distorted. Everything is so maximal and sumptuous but there is such clarity and extremity that it never becomes a cliché.” Yup, it’s a rare gift to be able to take on an entity as leached of all life as Dracula and totally resurrect him. Rather than offering you the Count as a slick aristocrat like everybody else, her costumes turned Gary Oldman into a haunted monster subject to multiple transformations. He’s a creepy androgynous ghoul whose epic cloak, she said, was supposed to “undulate like a sea of blood” and he’s a knight in armor that looks like flayed muscle rendered in heavy metal.

When I was secretly watching “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” on VHS as a milk-toothed demon child, it was obvious from the spooky lightning going through my body that the movie was hot, and not just because, in one scene, Sadie Frost (playing the doomed minx Lucy) bangs a werewolf during a summer thunderstorm. Like all the movies Ishioka worked on, it’s a mad Expressionist opera about love. The animal inside comes outside; danger and delight entwine. A lot of that febrile sexiness is transmitted by the costumes: straitjackets with batwings, too-tight corsets embroidered with evil snakes, luxurious midnight-black fur. Everybody is a werewolf.

They look like clothes that have been doing a lot of psychedelic drugs: vast, distorted, flowing through equally insane rooms like waves crashing on some otherworldly beach.

All of Ishioka’s work is powered by this ravishingly strange sensuality. Sometimes her costumes don’t even look like clothes but freaky industrial sculptures. Or they look like clothes that have been doing a lot of psychedelic drugs: vast, distorted, flowing through equally insane rooms like waves crashing on some otherworldly beach. Being an unstoppable polymath, she didn’t focus exclusively on the costumes but shaped the work of several departments at once (prosthetics, production design, set design) to create the whole world of the film. That’s why her filmography is like a genre to itself. There’s J Lo astride a white horse in “The Cell” in a huge snowy mountain of a dress swagged with sparkly fur like a Y2K version of Narnia’s White Witch! One of the bedrooms in “Mishima” is an orgy of gooey pink textures, as if the protagonist is sleeping inside a flower. Later on, a golden pagoda splits open wide like a book on fire and blinds somebody with its mysterious glow. “Dracula’s” aesthetics aren’t straightforwardly “release the bats!” Gothic but a kind of psychedelic decadence that feels simultaneously hyper-allusive to everything from Francis Bacon’s paintings (blood flows off the body like unstoppable silk) and entomology textbooks (she really loved bugs) to Diane Arbus and yet weirdly not of this world.

The luscious conundrum at the heart of Ishioka’s stuff is that mixture of “rich” and “visceral”, opulent and eerie, all of it oozing together to create a hot and sinister uncanniness, which is unique to her.

“Reference is only reference,” she explained in that documentary on the costumes for “Dracula,” “I never take a design element straight from the source.” One of Ishioka’s true descendents, the equally adventurous make-up artist Isamaya Ffrench tells me, “Ishioka’s work is so rich, so visceral. It draws from so many cultural markers that together they create a strange sensation of both belonging and alienation.” A paradox can be ripe with possibilities. The luscious conundrum at the heart of Ishioka’s stuff is that mixture of “rich” and “visceral”, opulent and eerie, all of it oozing together to create a hot and sinister uncanniness, which is unique to her.

One of Ishioka’s final commissions was to create the costumes for the misunderstood Broadway musical “Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark” (2010). She came up with outfits ideal for a rave held on another planet. The Green Goblin is a half-bug, half-gargoyle fiend in armor hard as a bank vault. There’s a creepy masked nymph named “Swiss Miss” (never seen before in any previous Marvel product) who twirls knives and seems to be made out of the same liquid chrome as the T-1000 from “Terminator 2.”

Ishioka was all about staying loyal to her concept, not admitting the littlest hiss of compromise that might stop her achieving what she dreamt up.

You don’t need to have been a virtuoso with needle and thread on the workbenches of Savile Row to deduce that these outfits might be a little difficult or painful to wear. Stomping around in his Dracula armor during the making of the movie, Gary Oldman yowled that he felt like “somebody trapped inside a car wreck.” (Thanks again to that documentary on “Dracula’’’s costumes with all its candid footage of wardrobe fittings—maybe the greatest DVD extra of all time.) Poor J. Lo asked if one of her costumes in “The Cell” could be more comfortable. In response, as she told the Ottawa Citizen in a 2000 interview, Ishioka said, matter-of-fact and extremely bad-ass, “No. You’re supposed to be tortured.” Maybe that sounds cold but then Ishioka was all about staying loyal to her concept, not admitting the littlest hiss of compromise that might stop her achieving what she dreamt up. (Her drawings of her outfits are so perfect and so close to the final product they’re scary, like Mozart’s manuscript pages in “Amadeus.”) Grace Jones never looked uncomfortable in her clothing but maybe that’s because it’s very hard to imagine Grace Jones ever looking uncomfortable. Ishioka created all the costumes for Jones’ “Hurricane” tour in 2009 . The killer number is the Disney witch frock she wears for her version of “La Vie en Rose:” gory red, a flower of evil blooming in a riot of spikes, scary and sexy, by which I mean “Grace Jones to the max.”

Nobody could rip her off because it would be just blatant and ridiculous, like trying to smuggle Pegasus through customs.

Since Ishioka was so singular, it’s weird to think about what her legacy could be. Nobody could rip her off because it would be just blatant and ridiculous, like trying to smuggle Pegasus through customs. (Grimes’ “Dune” princess dress at the Met Gala in 2021 probably made Ishioka’s ghost happy). Maybe it’s best to think of her as a magic potion, an insane stimulant that encourages you to go beyond whatever was there before, out to the wildest areas of imagination and bring whatever you find back into reality, hi-def and untouched whatever anybody else thinks. Copson tells me, “I return to her work all the time to remind myself of the freedom in total theatricality.” Make the thing that doesn’t exist yet, new and scary and wild, and make everybody shiver when they see it in a way that they never have before, and maybe never will again.