Illustrator Edward Monaghan's practice has taken years to perfect, but as he says the best things take time. Writer Alex Kahl speaks with him about how a change of scenery made him fall in love with his work again.

It was only at the end of my phone conversation with Ed Monaghan that he described his surroundings. Turns out he was sat in front of a large piece of stained glass he had been helping his mother make. She’s been in the business for a long time, and Ed’s been learning the ropes since he moved back home to live closer to her and the rest of his family in 2017.

It was around that time a few years ago that he was interviewed by AIGA Eye On Design. He had just decided to leave London and return home to Burnham, a quiet, leafy village in the county of Buckinghamshire. Throughout the interview – and by his own admission – he candidly describes his life in London as a time of anxiety and doubt. There he spent his time second-guessing the entire art scene and his place within it. In London, Ed noticed “a lack of appreciation of any kind of substance to things,” and that he was striving “to find something that did actually have some fucking substance.” Despite Burnham being the kind of place young people tend to want to flee from when they come of age, Ed decided to get out of London, and head back to where he came from.

Ed had been working as an artist in London for some time, and looking back now he remembers how manic a life it was. “You’ve got the choice to completely wear yourself down by doing both your personal work and your client work, or you can just do client work, or you can do personal work and go and live in a hut somewhere,” he says. Having chosen the difficult former option, he was quickly losing sight of what he actually enjoyed about his craft. Ed doesn’t consider himself naturally gifted, so every piece of work, both personal and paid, involves a lot of hard graft to get it to a place where he feels happy with it. “Eventually I just decided this wasn’t for me. I would’ve had to be anxious. If you have to juggle too much stuff, you get tired and you get frenetic,” he says. “And that’s no way to live. That’s the way a Fortune 500 executive lives. I just want a quiet, peaceful life.”

I want to draw together elements that might be disparate but might actually come into some stable form.

And that’s exactly what Ed has now. Where he once thought he wanted a life in the big city, chasing creative trends and attending the sort of “cool” events he thought he should be attending, he’s now totally satisfied with more serene existence in Burnham. This change of scenery brought with it a new perspective, and has given way to a new approach for him. “I think I’ve come to understand my own nature a bit more,” he says. “I don’t try to jolt myself with electricity to continually produce quickly and reshape my mind and put new foundations up.” Ed has realised that he’s simply a slow worker, and he’s okay with that. Each piece of work takes such a long time because he’s so meticulous. “Instead of trying to achieve a particular goal with the drawing, I try to find little contradictions within it and I look at it for a great deal of time,” he says.

He points to UK illustrator Pete Sharp as an example of an artist who can create at a fast pace, mapping the contours of an arm or the expressions of a face in seconds and bending them to his will with ease. “I don’t work like that,” he says. “I’m not an excellent draughtsman, but I can achieve things over time.” With his new environment and refreshed approach to work, Ed has managed to stave off the anxiety, keep the wolf from the door. He no longer worries about where to go from here.

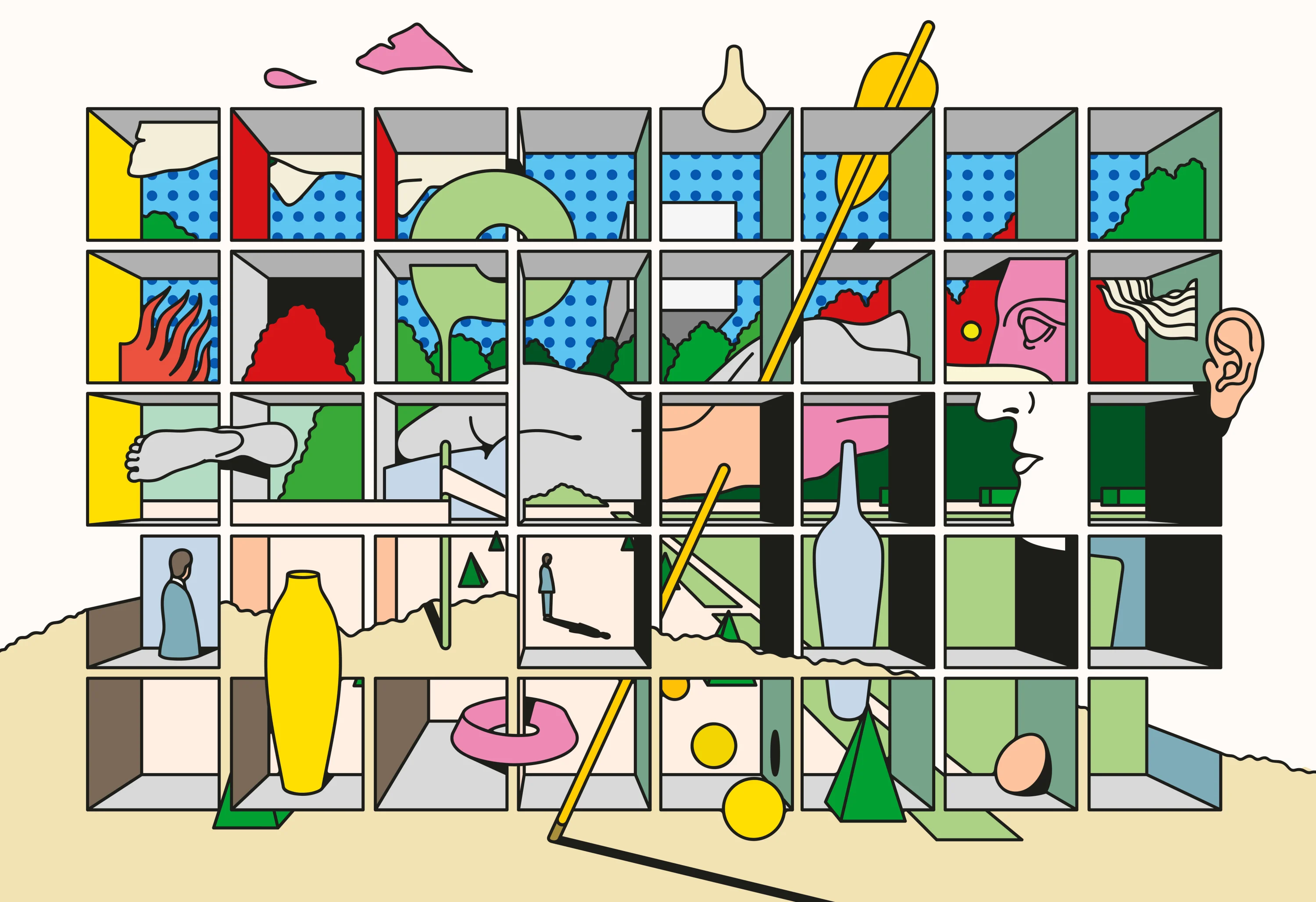

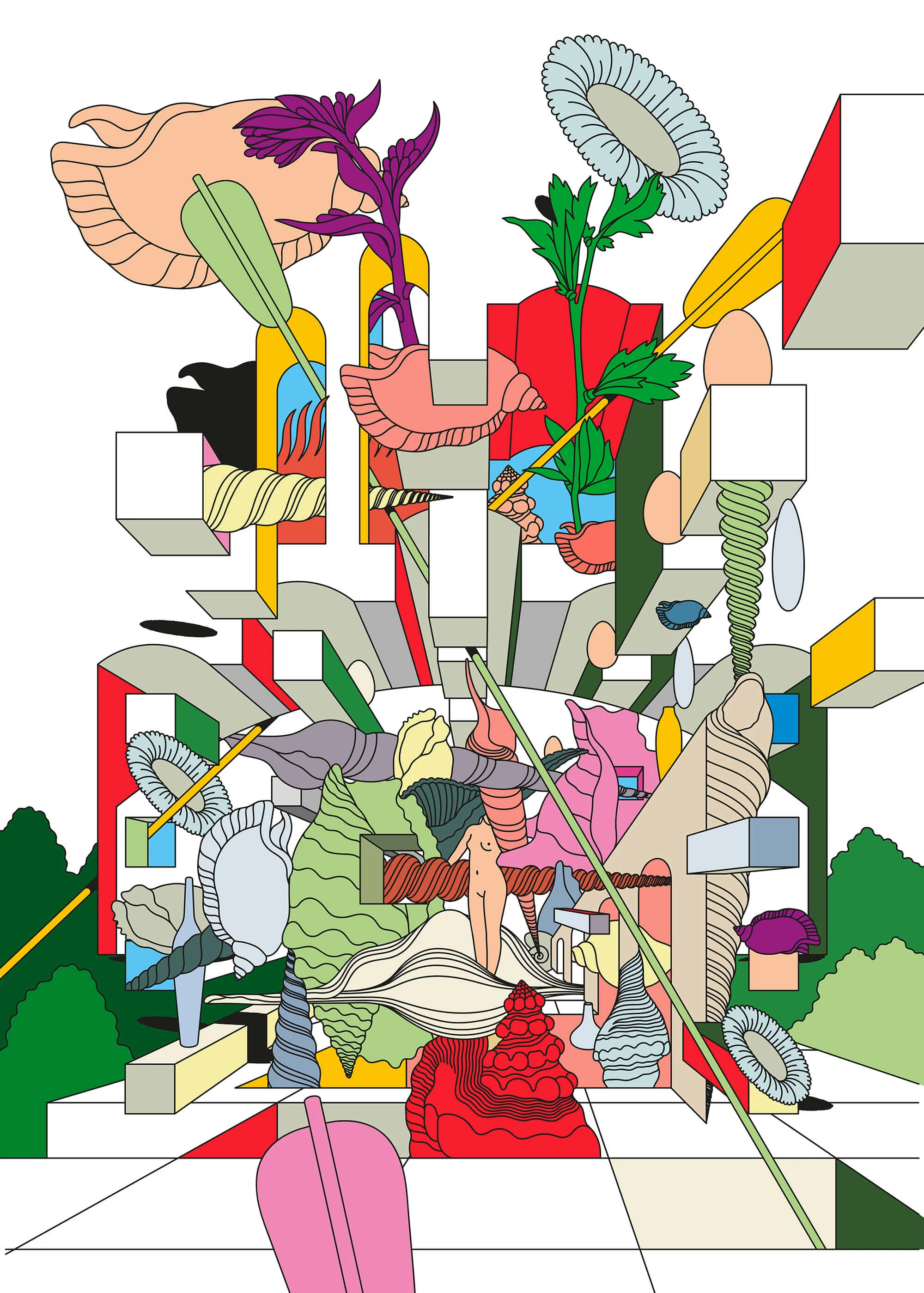

If his life has become quieter, his work certainly hasn’t. His escape from London has made his illustrations even more extraordinary. His latest work experiments with perspective, creating simulated universes and cultural bonfires. He starts off with a base structure, which could be a room or a landscape or an individual he’s been looking into. Besides that, the rest is all variable. “Lots of it is just a mix of pop culture references and other pieces of information that end up being combined into some sort of surrealist arrangement,” he explains. “Altered objects that might exist in real life become something different when you spend time ruminating on them.”

In one piece, a green arch is surrounded by pink-red tree stumps, with paintings of what seem to be nobles scattered around the scene, and arrows haphazardly flying and piercing every surface; “I was reading a book, and it mentioned a couple of Victorian missionaries and historical conquerors.” In another piece, perspective is played with as mythical chariots with boar’s heads fly high above mountain tops, and the head of Apollo sits in the corner. “I was just browsing some stuff about Celtic tribal Gods and pieces of bronze ware.” As you do.

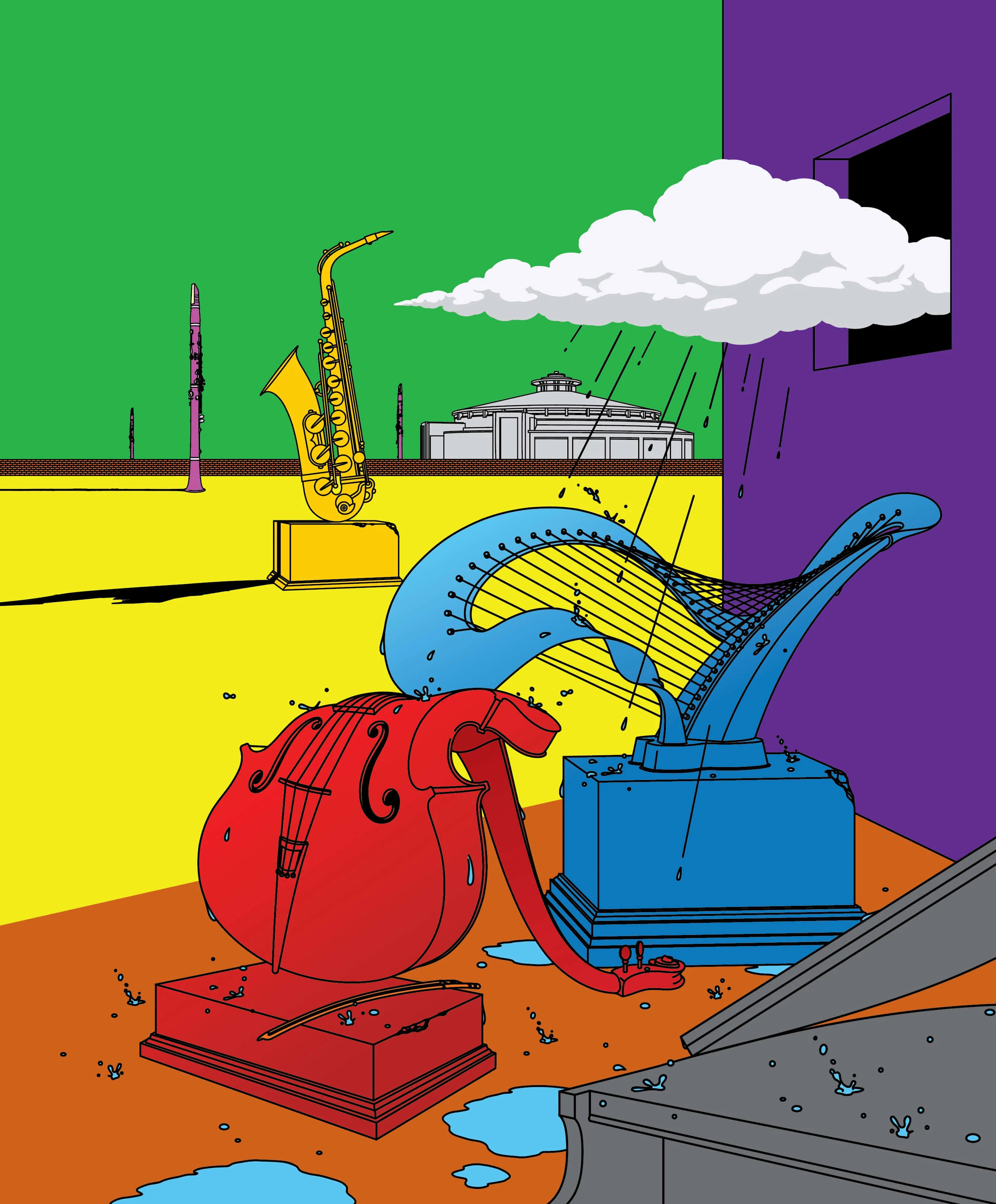

This seems too modest, even by Ed’s standards. There must be more to it than this. A lot of people browse stuff on the internet and look at obscure stuff in books, it doesn’t mean they all go off and make intensely complicated and surreal imagery. So many of Ed’s pieces contain such a complex and confusing mix of elements and references. A bell jar sits on top of a copy of The New York Times, trees dotted around within it with strange faces peeking out of their leaves. A violin made of billowing smoke and a harp being played by a stone statue. Majestic dogs and geese with saxophones for heads, and a skeletal conductor being birthed out of a little white teapot leading the whole chaotic symphony. This doesn’t just seem like Ed was reading something. This seems like the work of someone who sees the world in a very different way to the rest of us, and to other artists. But unlike the majority of them, he doesn’t seem to necessarily want to talk about it.

Alongside his personal pieces and most likely crazy search History, Ed still creates commissioned pieces, but he’s happily reached a point where he can always do the personal work he loves, and clients will pay him to do just that. A recent commission saw Ed being given the task of visually exploring sound. His response was an image crowded with sets of speakers outlined in the form of waves, a dolphin diving out of a gramophone made of birds, its base made up of bats and crickets. “Sonar and resonance, and the creatures that react to it,” Ed says. “If the topic is sound I’m never going to draw someone enjoying music or anything. That’s just not how I work. It’s all about what sound is. And how I can draw together elements of it that might be disparate but might actually come into some stable form.”

He comes across as a very different person to the one we read about in 2017. Ed seems clearly much more satisfied with his surroundings and with his output, but he still has goals and objectives he would like his work to fulfil. He’s also still pursuing the substance he was struggling to find then. Interestingly though, beauty is not one of the values he’s focused on. “When you go to a Tibetan temple or to see relics, you can understand what beauty is,” he says. “Humans require a bit more. I’m more interested in things that are all-encompassing.”

One of these all-encompassing values is longevity. Ed points to brutalist buildings as he begins to outline his point, and notes that people around the world love to visit them, marvelling over their structure. But, he states that there will always be something magical about the ancient style of construction. “You can tell that people want to be around, in greater density, the older buildings in London than the newer ones,” he says. Ed feels that the newer buildings in the city are oppressive, and that the light only falls on them in a certain way, while a building with majestic pilasters and columns has been designed with the idea in mind that shadows will fall across it. “It’s been designed with time in mind. Modern buildings aren’t designed like that. You have to have a long-term consideration,” he says.

Ed seems to have realised that above all else, creating something that stands the test of time and connects with people from generation to generation is the pinnacle of being a creator, and this is something he has now started to pursue in his own work, and with his mother’s stained glass business.

“This glass is something that will be shown in the town that I grew up in and it will be taking influences from the natural elements of the locality. It’ll be related to Burnham Beeches, an important place that means something to people,” he says. “All those things elegantly put together will hopefully satisfy more people on a higher level than another piece of work.”

I suggested that something such as this piece, even if it was only seen by a few thousand local people, might have more of an impact than a piece of art on social media that’s seen by millions. “Yes, absolutely. There’s no doubt about it,” Ed says. “When you see things online, you’re going through the mimetic chain. More people like it, you think, so should I like it as well?” Now, Ed is more focused on the people who can truly appreciate his artwork – be it his own illustration or a piece of stained glass – and he hopes the 12000-strong population of Burnham will appreciate the glass sitting before him. “I won’t be able to delete this thing me and my mum are making. Hopefully if it’s good enough, people will want it to remain here forever.”