Minnesota’s Twin Cities is where Prince created one vision of the future, and from there Dua Saleh is writing another. Growing up in the historically Black neighborhood of Rondo, they saw multiple storytelling traditions collide: hyper-experimental slam poetry, and the meditative recitations of Arabic poetry and Qu’ran. Dua Saleh draws from both – and everything else, it seems – to make free-ranging lyrical soundscapes that sit comfortably between genres. Writer Anupa Mistry speaks to them via Skype as they talk about life in self-isolation, learning to perform at open mics, and the potency of reimagining old stories and traditions.

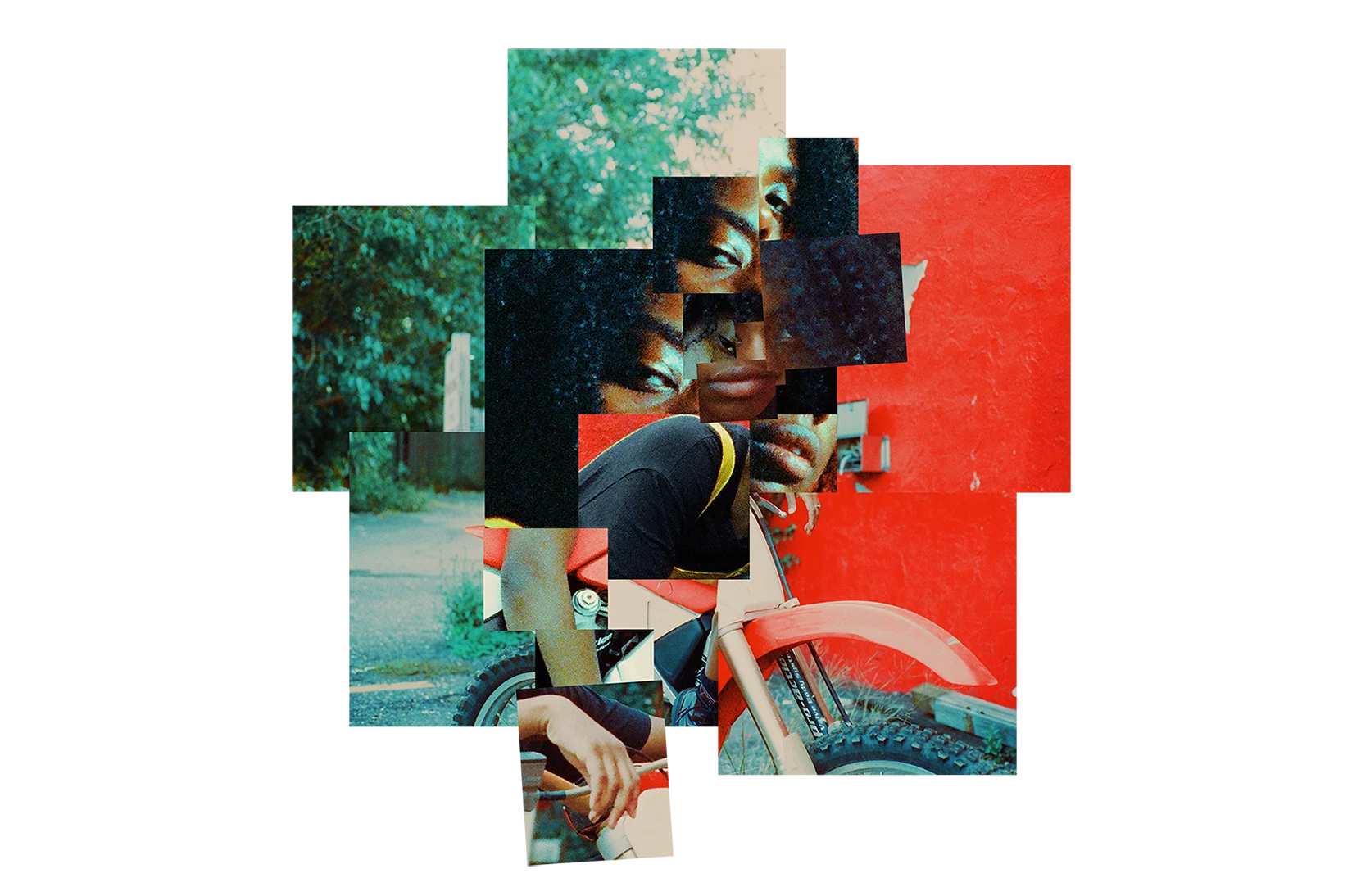

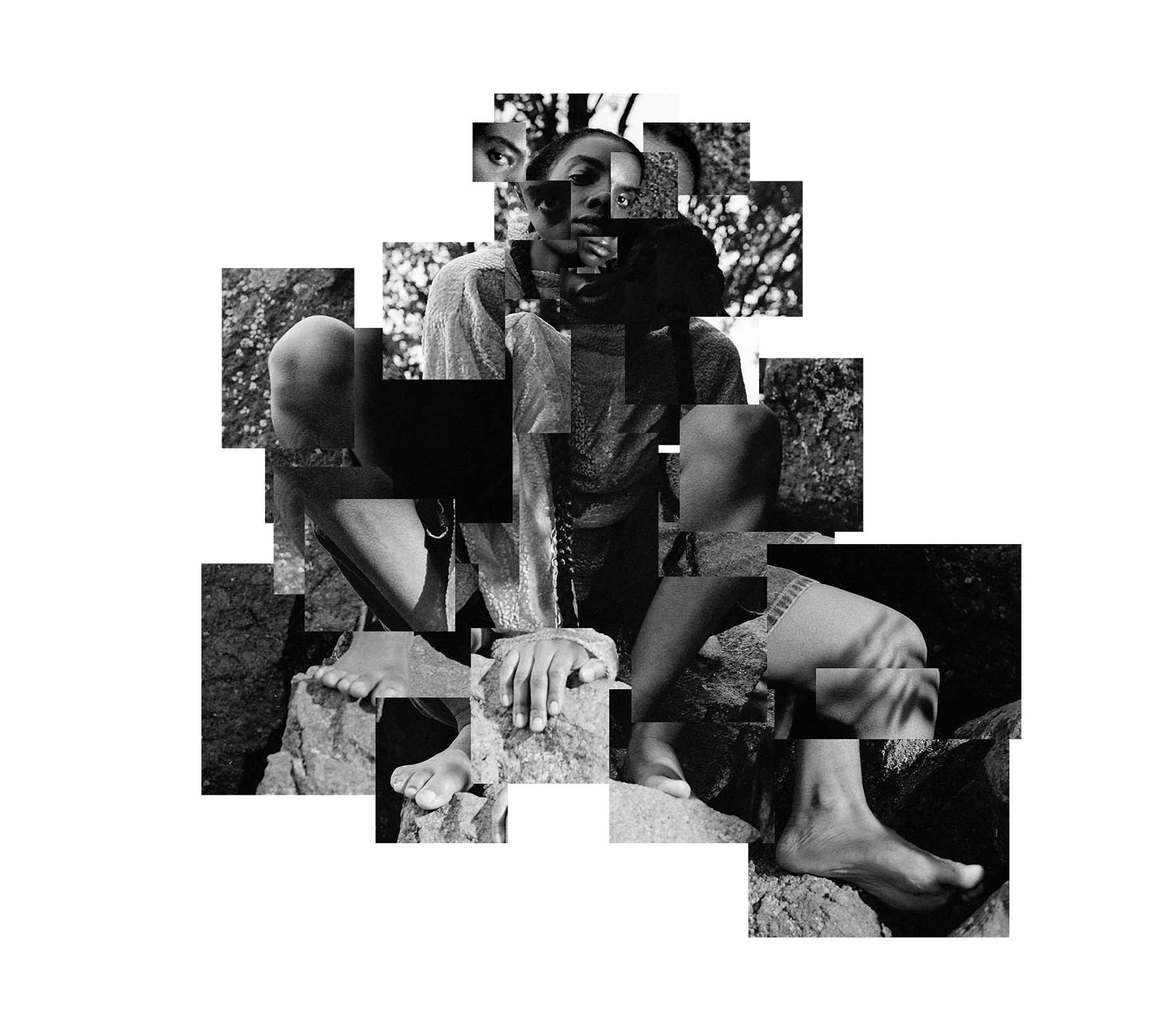

Artwork by Lunga Ntila.

There is the seed of something hopeful in self-isolation for Dua Saleh, who is currently holed up in an apartment building in Minneapolis. “I’m perceived a certain way when I walk out the door unless I’m wearing a mask,” says the 25-year-old non-binary musician over Skype on a grey Friday morning. In music videos and performances online, their hair is often pulled back in braids, but today it erupts in a mass of tight, glossy curls. “It’s been kind of weird but kind of cool to wear a mask and have people think I’m a man in public.” A shy smile, and then they’re quick to clarify: “That’s not necessarily what I want, but it’s better than being automatically perceived as a woman.”

It’s the first day of Ramadan, a big deal particularly in a city that houses one of the largest Somali diasporas in the United States. Dua Saleh, who was born in Sudan, lives in an apartment complex that’s also home to many East African families. Ramadan is complicated, “because I’m not really religious,” but the day prior they retweeted a clip of the azan, the five-times-daily call to prayer, being broadcast from the roof of a local mosque – an American first. They also woke up early for suhoor, the pre-dawn meal that’s eaten before fasting during daylight hours. “I tried to pray,” they add, “but my body was like, ‘Nah, not today.’”

Still, similar to many who question the faith traditions of their childhood, the holy occasion provides an anchor of familiarity and the chance to deconstruct. Some Muslims abstain from music during Ramadan, but Dua Saleh hopes to spend the month re-connecting to their creative practice, reversing the ambient pressure to stay productive during quarantine with a new EP, ROSETTA, on the horizon. “I’ve just been going a little too intense listening to music, trying to find things,” they say. Behind their right shoulder I see the vinyl sleeve for Aretha Franklin’s I Never Loved A Man The Way I Love You. They’ve been listening to children’s recitations of the Qu’ran on YouTube as a way to connect with pentatonic scales. “ have a higher range. They’re able to do more with their voice – and, in my mind, I think is less contrived. Kids probably have a lesser concept of what is good and evil.”

As a child Dua Saleh’s family was displaced by the second Sudanese Civil War. After spending some time in an Eritrean refugee camp the family ended up first in North Dakota, before settling in Saint Paul, Minnesota, where Dua Saleh attended both high school and college. “When I was younger I had a lot of trouble connecting with people and so that led me to self-isolate a bit. I read a lot, I wrote a lot of poetry,” says Dua Saleh. “I was also angry and having trouble expressing my queerness.” They experienced tension in having access to safe spaces, like their high school Gay-straight Alliance, but a home environment where gender norms – like feminine clothing – were enforced. But Dua Saleh was also anchored by a deep understanding of their family story and their mom, who safely shepherded three children from East Africa to the Midwest, kept up a hobby of painting with watercolours, and taught Arabic on weekends to children in the local community. “I’m a bit of a clown, and I’ve always been able to find joy. It’s the only thing that’s gotten me through life,” they say. “Yesterday I was watching LEMONADE and I just broke down, but midway through the breakdown – I don’t know what it was – something just cracked me up about the way I was crying!”

I was shaking, sweating buckets, but people liked my words.

This self-awareness is evident in Dua Saleh’s music, which comprises autobiography as well as a background in slam poetry and a burgeoning interest in theater. Their first EP, 2019’s Nūr, is a lyric-driven collection of songs from the voice of a performer who has a canny understanding of presence – and its inverse, the feeling that space, silence, an incomplete sentence can elicit.

“I got spoiled by the poetry scene in Saint Paul,” they say. “There are a lot of open mics and there was one spot, Golden Thyme, which was within the same block as my house in Rondo, which is a historically Black neighborhood.” Every Thursday, a teenaged Dua Saleh would attend the ReVerb Open Mic night as part of a community-based youth program to watch people from the neighborhood take the mic. “Slam poetry is this Black art form that’s been co-opted by a lot of non-black people, so everybody knows that traditional style of hip-hop spoken word, but I saw it performed in a less generic way,” they said. “Seeing it from people who were experiencing or have experienced domestic violence, or people who were literally still slinging rocks — it changes the context to have that natural element of people from my environment as the performers. It meant something to me.”

When they finally got up on that stage, at 17 or 18-years-old, “I literally almost threw up. I was shaking, sweating buckets,” they say, laughing. “But people liked my words, and they offered a lot of necessary critique. I was always there and people knew me, so they held me.”

Dua Saleh didn’t have to decamp to a coastal city to find love and belonging. Instead they tapped into new sensations through unassuming mediums, like manga comics. “There was this one called Skip Beat! It was about this girl who wants to become a performer, and she was in this program about acting and learning how to seek out love from a crowd and something about it just stuck with me.” Dua Saleh says it helped them connect to a deeper impulse behind yearning for validation from poets in their community. “Now I’m actively seeking out validation from trans, queer, non-binary people and people outside of the spectrum who don’t have access to the liberty that they want or need.” It is a form of seeking love, they concede, but it’s generative.

In June, Dua Saleh will release their second EP ROSETTA, inspired by the legendary Black rock and roll musician Sister Rosetta Tharpe. It’s also a lesbian fantasy story, about Rosetta’s relationship with the pianist Marie Knight. “I was thinking about the sonic implications of their love, because they were these extraordinarily talented songwriters but love comes with grimy things too,” they say. “And at that time, you had to be the best of the best.”

I’m just paranoid of being perceived in general.

In the 2018 book, Looking For Lorraine, the scholar Imani Perry meticulously reconstructs the brief life and inner world of the playwright Lorraine Hansberry, who died aged 35. Perry contextualizes the conditions that led Hansberry to become, in 1959, the first Black woman playwright to mount a show on Broadway: A Raisin In The Sun. But she also queers the established biography, using letters and articles and other documents from Hansberry’s archive.

“ere she alive or reincarnated, she could be an out lesbian and loudly unconflicted about her myriad identities,” Perry writes in the book’s introduction. “It is a story that disrupts her obscurity.” Dua Saleh's ROSETTA is a similarly speculative offering.

Working with their long-time production partner Psymun, Dua Saleh dug up old demos and crafted new ideas for ROSETTA. The lead single umbrellar, draws on Psymun’s rock influences and finds Dua Saleh moving away from cleanly constructed bars toward melodic pop hooks with an aggro bent. On Smut, they sing in Arabic, reworking the “very gender-specific” language to play with pronouns and pre-existing associations, creating a contemporary vernacular.

Within the Twin Cities poetry community, they’d see queer Muslims and other racialized people experimenting with pronouns and gender identities in English and vernacular. “This isn’t unique to me,” they say. “I’m surrounded by people who consistently do this. But because I don’t read or write in Arabic I have little context for it, outside of spoken word.”

It’s easy to project an aspirational narrative onto Dua Saleh’s disruptive artistic practice, their project of neatly undoing and making visible a tangle of thought-to-be-knotty intersections for a brighter future. But it’s not without pressures: the music-making process itself is a small respite of freedom and fun from the emotional quicksand of the public eye. “I’m just paranoid of being perceived in general,” they say. After years of student activism in both high school and college, Dua Saleh is ambivalent about the surveillance that comes with visibility – there is a long history of states spying on Black community organizers – as well as the larger visibility of “growing up in a Muslim household, a refugee household, a Black household. We’re very aware of being watched.”

And yet Dua Saleh is so watch-able: giving a masterclass in seduction and bravado with a mere flick of the wrists, the hooked lure of sharp lyrics delivered with a smile in their COLORS set, or curving their body into living sculpture in the umbrellar video. But these images aren’t total; like walking outside with a face mask, they’re just the parts of Dua Saleh that want to be seen.