Toronto-based artist Stefana Fratila’s album “I want to leave this Earth behind” is an attempt to capture the sounds of the planets in our solar system, and it’s the product of five years of research using calculations by NASA astronomer and planetary scientist Dr. Conor Nixon. She walks writer Sajae Elder through some of the tracks, and explains how they reflect the ecosystems and atmospheres of the planets they’re named after.

For the many advancements astronauts, scientists and researchers have made exploring the great depths of the solar system, it seems difficult to imagine we’re largely unaware of the vast sonic possibilities of the planets. Our most common understanding of space is as a vacuous unknown, where—as it's often said with horror film-like macabre—nobody can hear you scream.

Since 2018, Toronto-based artist Stefana Fratila has been trying to address the question: if each planet in our solar system were a different room, what would each room sound like? In the earliest stages of what would eventually become “I want to leave this Earth behind,” a conceptual album that explores the answer to just that, the lack of existing sound elements lead Fratila to embark on five years of research alongside NASA and a residency at the Mexican Center for Music and Sonic Arts. “I just sort of assumed the plugins already existed, to be honest,” Fratila explains. “I was hoping to emulate how Saturn sounded for a track, and when I looked up the plugins, I realized they didn't exist.”

The resulting eight-track album, each named after a different planet, is an audio journey through the cosmos based on how sound would likely travel through each planet's atmospheric conditions, scale, and surface elements. On Venus, its extreme heat and molten lava surface comes to life as a deep warbling bubble, while the intense centrifugal force of Saturn’s rings keeps in mind the likelihood that particles reverberate as they pass through the rings and crash into each other.

In addition to the album, Fratila’s ongoing creative research also culminated in Sononaut, a collection of 8 open-source VST plug-ins made alongside artist Jen Kutlet and including detailed research notes using calculations by NASA astronomer and planetary scientist Dr. Conor Nixon. “The plan was always for a big part of the ethos of the project to be open source,” she explains. “As a music producer, I get really excited when plugins are open source. I wanted something that could be improved or changed or updated by other people.”

While extensive research went into the project, Fratila was excited by the idea of using these findings to take creative liberties that would ultimately make the project feel like a journey in and of itself. “I think part of the wonder of the project and of the excitement for me was knowing that there wasn't a way to be completely accurate with it,” she explains. “Because we just don't know—and we won't know for a really long time—how sound travels through these specific atmospheres.”

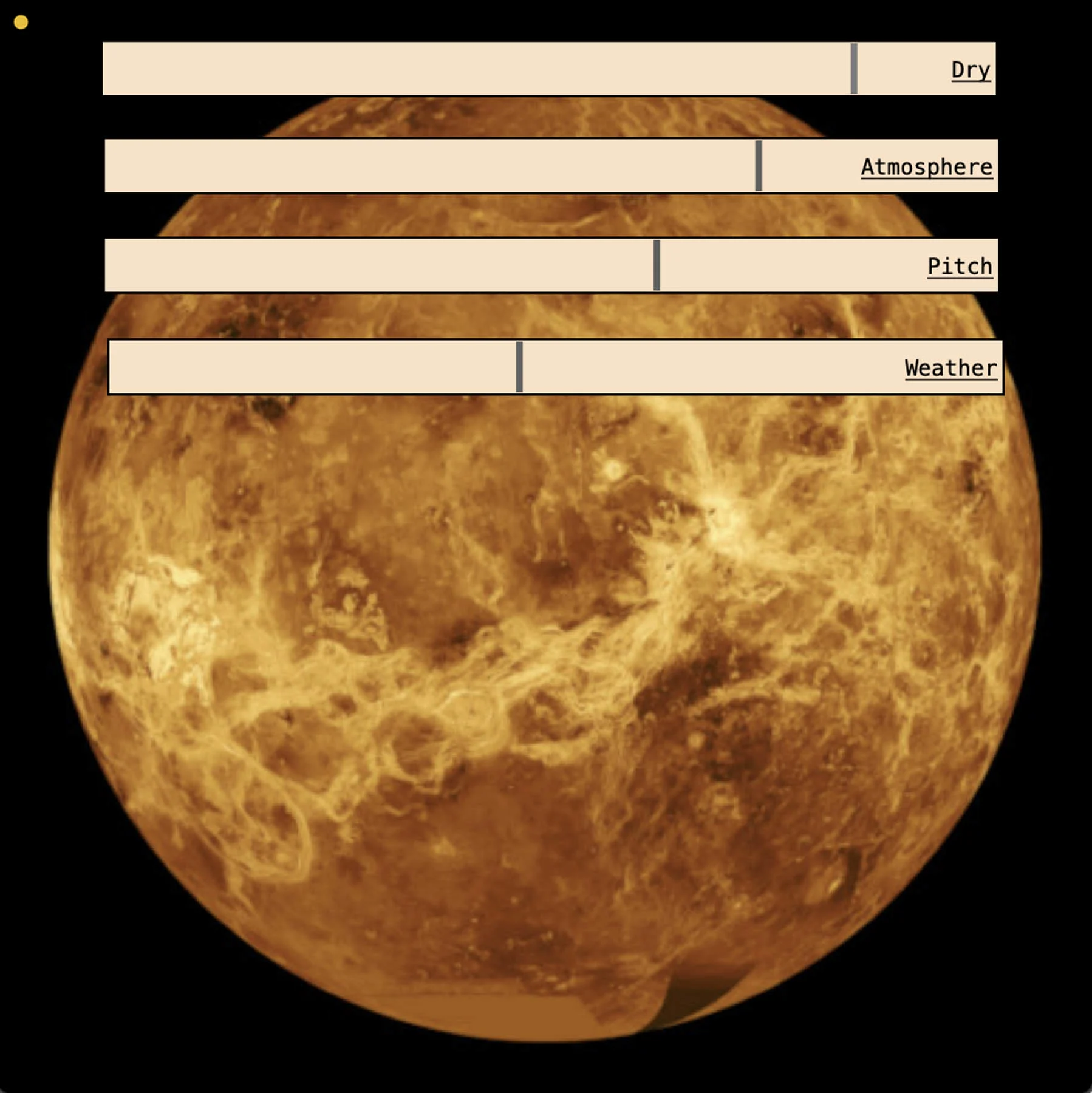

Venus

Recorded over the course of 2019, Fratila says the process for each of the tracks all had a similar starting point: creating audio loops to represent the weather systems on each planet and writing additional elements from there. “I would listen to the weather while writing the music and while recording, and then I would go through and I would do each layer one by one, each synth or each midi layer or whatever else I was doing,” she says—in Venus, she found a particular interest in the planet’s temperature and its effect on the way sound travels around it—“I feel like Venus geographically is kind of interesting because it is really, really hot. So I thought a lot about the sound of bubbles and gurgles and things like that. It has a very interesting history and geographical features, so there was a lot to play there in terms of sound. You can definitely hear the volcanic activity,”

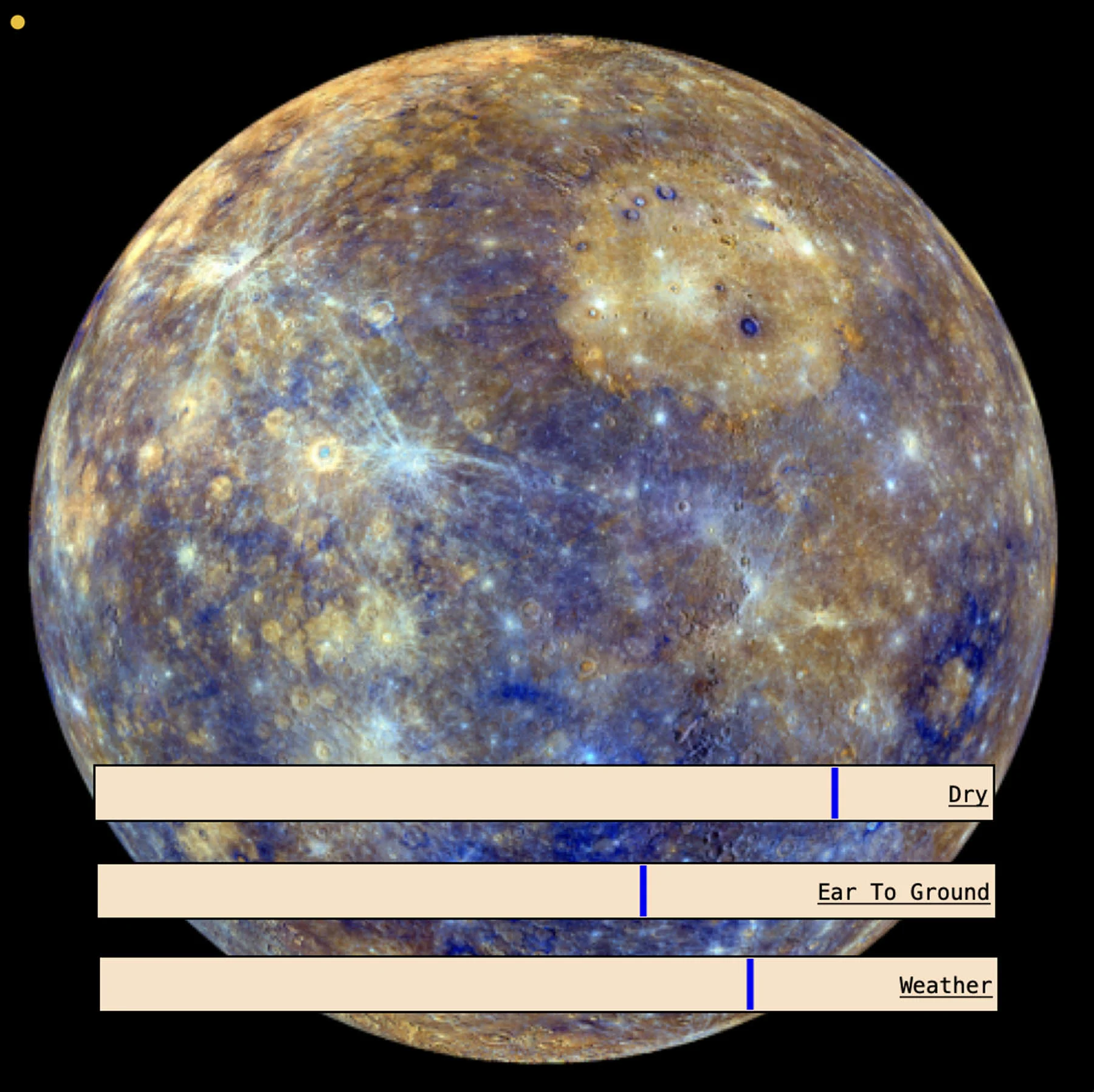

Mercury

Without an atmosphere, measuring the way sound travels through Mercury proved complex in comparison to the other planets. Despite this, Fratila’s workaround focused on the way sound may travel directly through the solid mass of the planet itself, instead of around it. “I decided to think about how sound travels through solids. That one is conceptualized as if the person using the plugin is listening through the ground on Mercury,” she says. “Mercury also has quakes, like earthquakes, so a lot of that track is made up of lower frequencies and how I’ve envisioned these quakes.”

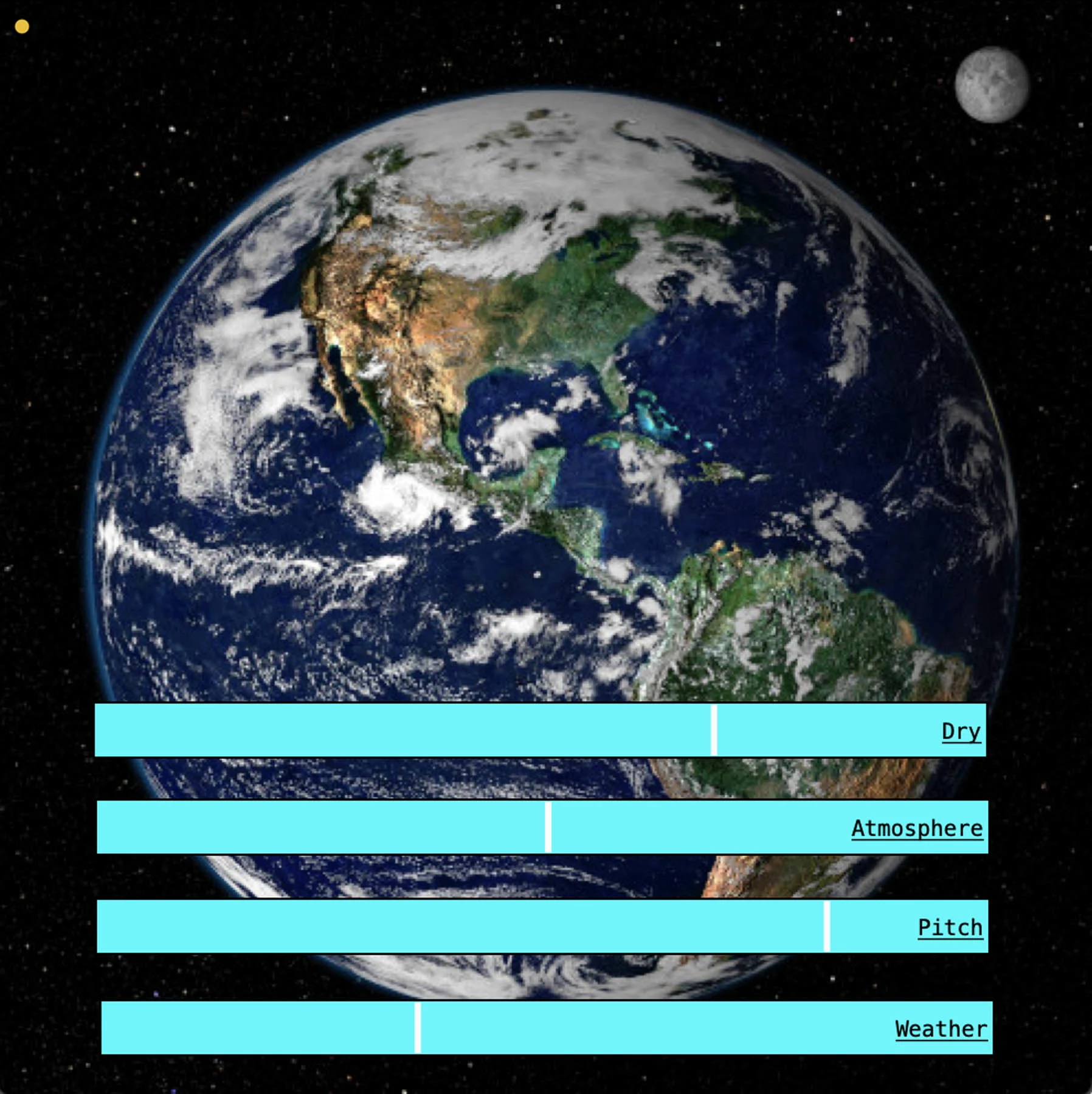

Earth

Unsurprisingly, water and the life it supports were the most important elements guiding the sounds of Earth. “It rains on the other planets, but it's not raining water. And those gas giants [where it also rains] don't have a surface, so the actual sound of the rain wouldn't exist anywhere else,” says Fratila. “So, Earth was definitely focused on water and also this idea of sound emitters; so anything else that’s alive and making sounds like insects, birds, and other animals.”

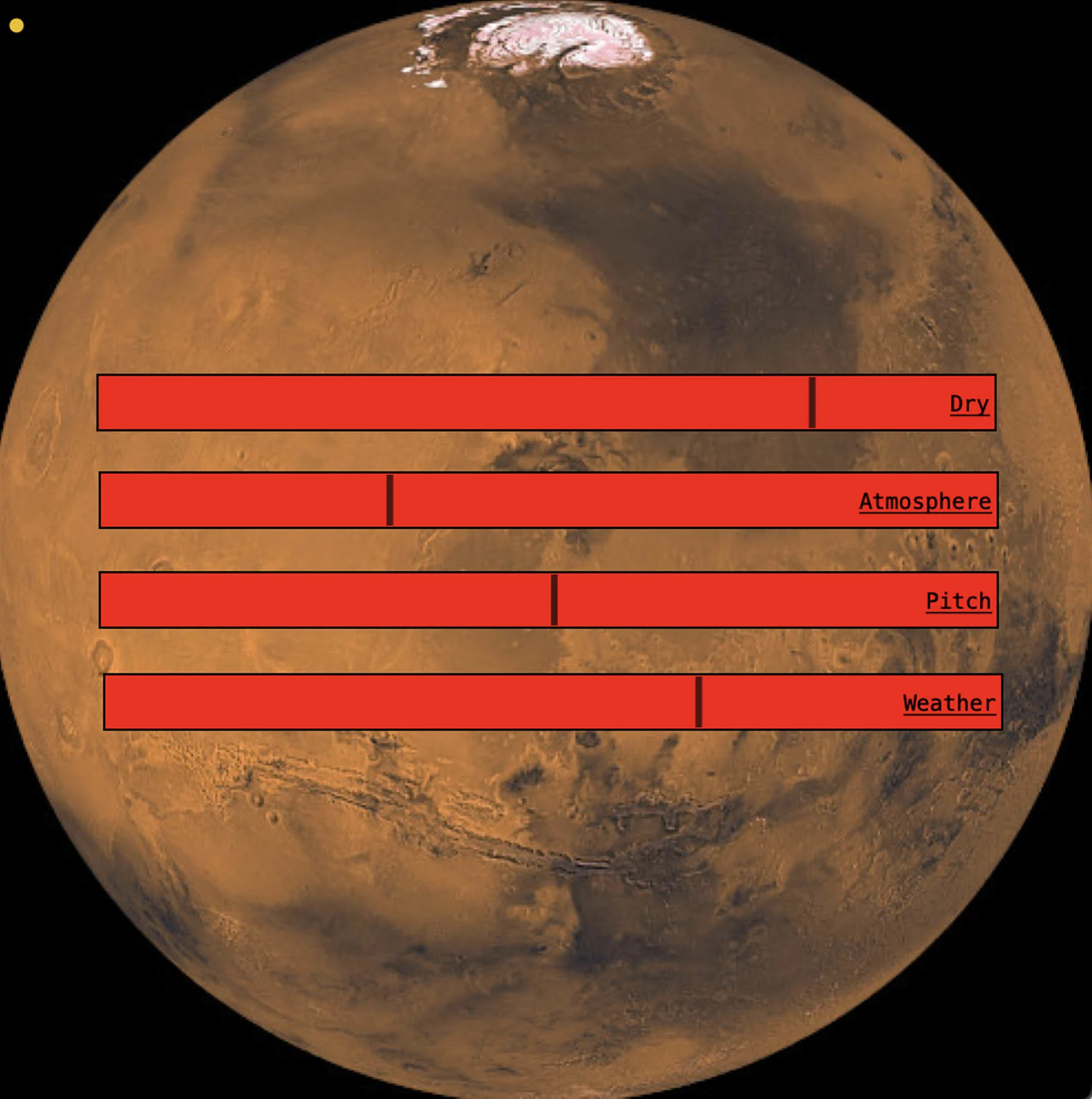

Mars

As the planet in our solar system that has been the most extensively studied and visited by scientists here on earth, we would eventually come to know what its atmosphere actually sounds like thanks to the Perseverance exploration surface rover sent to the planet in March 2020. By then, Fratila would have already created the planet’s sonic landscape on her own, but she was pleasantly surprised that her research findings were similar to the rover’s own recordings. “I knew that was coming when I first came up with this idea, so I was very excited to track that progress,” she says, before going on to explain how she approached crafting the planet’s plugin sounds. “Part of the concept for Mars was this idea of the wind kind of being faster than on Earth, but sounding softer. That was a difficult thing to translate. The idea of these particles getting picked up or just drifting by—these kinds of things were specific to Mars.”

Neptune

As the final planet in our solar system, Fratila knew she wanted its namesake track to mark the end of the journey. Slightly more imaginative than the others, she wanted it to feel dramatic, distant, and unfamiliar, specifically because it’s one of the planets scientists know the least about. “Uranus and Neptune were the most challenging planets because they’re so far away, and they were a little difficult to draw a distinction between because they’re both very cold and windy,” she says. “I really took liberty there and just really went for it with the music. It’s a pretty wild end of the journey, and that's a pretty cacophonous track.”