The conversations we have while sharing a meal can be part of some of the most important of our lives. Look behind the scenes of major upheavals, wars and ideological disputes and you’ll often find a carefully crafted meal bringing the protagonists together.

Here, London-based creative studio Bompas & Parr take a closer look at “diplomatic dining” and explore the effect some of the most important meals in history have had on the world we live in. By venturing inside embassies and restaurants and consulting with serving diplomats, they lift the veil (or the tablecloth) on the toasts, roasts and what really goes on in the dining rooms of power.

Photos by Charlie Surbey.

The power behind the plate and the underlying psychology of shared dining has been shown again and again to be an art form of the most exquisite nature. For centuries, the dining table has been recognized as a unique forum where negotiations can be fought, differences settled and relationships sealed.

Diplomatic dining has been deployed as a political tool before, during and after many of the major upheavals, wars and ideological disputes of the 19th and 20th centuries. Even today it continues to be a useful diplomatic mechanic between nations, in the interests of maintaining cordial and constructive working relationships – although it would be facile to suggest it could be a panacea for the scale of some of the problems the world is facing right now.

As examples of diplomatic dining go, Stuan Stevenson’s wonderfully titled “The Course of History - Ten Meals That Changed The World'' gives intricate detail and insight into the big plans, minutiae and political context of meals that shaped history. For instance, few can rival the spectacular largesse of the masked ball and feast hosted by the Emperor and Empress of Austria in October 1814 as part of the Congress of Vienna.

Some 10,000 guests—the cream of European society—attended the Hofburg imperial palace, to dine on a lavish meal conceived by the celebrated chef Marie-Antoine Carême. The guest list included two emperors and empresses, four kings, one queen, four heirs to thrones, two grand duchesses and countless princes and princesses. Collectively they represented allies and former foes who were now meeting as victors of Napoleon to agree a new vision for Europe.

Over dishes made from Carême’s mighty shopping list—which boasted no less than 300 hams, 200 partridges, 600 ox tongues, 3,000 liters of soup and a veritable fountain of wine—the guests were beginning the process of dividing up the continent and restoring the balance of power to forge lasting peace.

It is perhaps ironic that Napoleon had been acutely aware of the diplomatic power of dining himself. In 1803, he had purchased the magnificent Château de Valençay, where he installed his chief diplomat Tallyrand with the specific intention of using the location to forge alliances using the culinary skills of the very same chef, Marie-Antoine Carême.

Leave your sword at the door

If the 1814 feast was an uncharacteristically large gathering, it nonetheless effectively illustrates that collectively consuming food bestows extra significance on events, particularly at moments of great historical importance.

It therefore may come as little surprise that it was over an extravagant dinner in June 1790 that Founding Fathers of the United States Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and Thomas Jefferson ended a deadlock over where the new capital of the United States should be located.

Meeting at Jefferson’s house in New York, and consuming courses of capon stuffed with Virginia ham, boeuf à la mode and Baked Alaska, the three men decided how the Revolutionary War debt should be apportioned across the states and, putting aside ideological and personal differences, agreed to locate the capital on the banks of the Potomac—an agreement fueled, no doubt, by each course being paired with fine wines.

The combination of dinner with diplomatic intent imposes formality, grandeur, civility and sophistication—voices are lowered, and swords left at the door.

What becomes clearer is that the combination of dinner and diplomatic intent appears to impose layers of formality, grandeur, civility and sophistication to proceedings of all sizes. Sociological studies have shown that sharing a meal is a powerful motivator: not only does it enhance our receptiveness to whatever is discussed, but it also triggers a desire to “repay” the provider.

Dining together, it might be said, is not just about food, but how the hormones and emotions unleashed by consuming it in a shared forum can influence the way we think and respond. Be it state banquet or low-key embassy supper, dining together tends to demand voices be lowered and swords left at the door. The 19th-century British statesman and prime minister Viscount Palmerston referred to dining as the “soul of diplomacy.” It was Winston Churchill, a famous bon vivant, who ultimately coined it “dinner diplomacy.”

It doesn’t always have positive outcomes. Adolf Hitler used a veil of civility presented by dining to force the hand of his guest, Austrian chancellor Kurt von Schuschnigg, during a dinner at the Berghof in the Bavarian Alps in February 1938. After a genial start, the dining table, set with fine linens and Swastika-clad crockery, became a bullying pulpit from which Hitler outlined his ambitions for Austria, presenting a list of non-negotiable demands for how the country should concede independence. After schweinwürst and sauerkraut, von Schuschnigg had little choice but to agree to the complete integration of Austria into the German state.

The development of ‘soft power’

Today, the concept of diplomatic dining remains strong, recognized as a state instrument of what has become known as “soft power”. Popularized in 1990 by American political scientist Joseph Nye, it refers to the ability to co-opt rather than coerce. The chefs charged with preparing special state culinary moments certainly recognize it as such. In 1977, Le Club des Chefs des Chefs was formed, its membership comprising personal chefs of heads of state, meeting under the motto: “If politics divides people, a good table always gathers them.” Still in existence today, its 14 members include Cristeta Comerford, executive chef at the White House; Ulrich Kerz, chef to the Chancellor of Germany; Guillaume Gomez, head chef at France’s Elysée Palace; and Mark Flanagan, chef to Her Majesty Elizabeth II, Queen of The United Kingdom and Head of the Commonwealth.

Hillary Clinton, speaking in 2012 as Secretary of State (the United States’ top diplomat), summed up the modern viewpoint: “Sharing a meal can help people transcend boundaries and build bridges in a way that nothing else can. Certainly, some of the most meaningful conversations I've had with my counterparts all over the world have taken place over breakfasts, lunches and dinners. [Food] is the oldest diplomatic tool.”

George H. W. Bush made history by becoming the first sitting president to vomit on the prime minister of Japan.

Moments of great political symbolism are often driven by great diplomatic dinners. In 2013, President Barack Obama served British Prime Minister David Cameron a main course of Bison Wellington, giving an American twist to a classic British dish, representing “a great marriage of the two countries.”

At the 2018 Korean Peace Summit, everything from the shape of the table to the ingredients and the provenance of each dish took on special significance. The choice of minced croaker and sea cucumber as a dumpling filling referenced the hometown of South Korean President Kim Dae-Jung; while rösti, the traditional Swiss potato fritter, referenced where North Korean leader Kim Jong Un was schooled. A mango mousse, decorated symbolically with a map of a unified Korea, was encased in a hard chocolate shell which the leaders had to smash through—jointly holding a large hammer—referencing the warmth of their relationship breaking through.

Despite the best of intentions, things can, and will, go awry at what can be sensitive moments. During a visit to Japan by then US President George H. W. Bush in 1992, he made history by vomiting on the prime minister of Japan. The faux pas, during a state dinner, is thought to have set US-Japanese relations back several years and made Bush a target for disdain in Japan.

Modern-day diplomatic dining: the working lunch

The reality of diplomatic dining today is that the working lunch, more than official state dinners, has become the workhorse of the format, conducted at embassies and missions globally on practically a daily basis. See our accompanying features and photostories.

“During the conduct of diplomacy people have to eat. The question is how to do so in a way that supports the objectives of the event,” says Paul Brummell, a serving UK ambassador and former head of soft power at the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office in London. Even apparently informal meals are stringently planned: who are the guests, what’s on the menu, what dietary and religious issues need to be considered, where is it to be held, and how can the best response be elicited from guests, are all essential questions.

“Because of the nature of a meal, it has advantages and disadvantages for doing business. You’re not sitting there with a pen and paper, so a meal doesn’t suit going through a draft treaty,” he says. “But that disadvantage has a flip side: it is more relaxed, so provides a better opportunity to tackle knotty issues where a more formal context might lead to more inhibited discussion. And rather than a seated dinner, inviting guests to, say, a traditional English afternoon tea can make the context feel even more informal and friendly.”

In general, sensitivities about causing diplomatic incidents tends to restrict the range of foods on offer. Asparagus and sea bass are ambassadorial staples. “Because of the nature of diplomacy, you are not doing things to provoke or annoy, but to build bridges and make connections. This tends to place certain limitations on the menu, but there’s still plenty of scope for experimentation and doing things out of the ordinary.”

Foods that risk offending cultural or religious values tend to be permanently off the agenda (pork is controversial here), as are foods that are messy to navigate, so lobster’s out too. During my posting in Romania, we were trying to showcase British food and drink and pay respect to local Romanian food and drink—we’d mix it up with a local first course and British main course,” adds Brummell.

(That said, the choice over what is on the menu can, on occasion, seem remarkably pointed. Consider the scallops and turbot served by the European Commission to former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, in December 2020, during 11th-hour negotiations on Brexit, much of which hinged on European rights to British fishing waters.)

And for all the planning that goes into such events, diplomats attending as guests may face the odd high-risk dining table challenge. “There’s a tradition in Kazakhstan to give a sheep’s head to an honored guest, who must allocate pieces of it around the table,” says Brummell. “The etiquette around the process can be quite elaborate, as you are supposed to assign pieces according to the qualities of the other guests.”

Such isolated incidents aside, and notwithstanding global acts of aggression and aggrandizement that require being dealt with in hard-power political and military terms, diplomatic dining will likely continue to be valued for its soft power. Its ability to bring different nations, viewpoints and opinions to the table, using the principles of appeal and attraction, reinforces the tone for how most nations coexist and evolve together.

As Anthony Bourdain neatly summed it up: “Barbecue may not be the road to world peace, but it's a good start.”

The Czech Republic: a culinary bridge to the British soul

“Bonding over a meal”, says His Excellency Libor Secka, the Czech Republic’s former top diplomat in the UK, “is a way of discovering the soul of a country”. Having previously held posts in China, Italy, Belgium and Mexico, Secka is well-practised in seeking them out with his wife, Sabrina.

When in London, they regularly welcomed figures from the worlds of sport, culture, business and all sides of the British political spectrum to their official residence in Hampstead, in north London, for a lively dinner prepared by then Chef Radek Kludka—opting to use their home rather than the embassy to entertain guests. Proudly conscious of their country’s position in Europe, both geographically and politically, they offer a carefully curated selection of Czech cuisine.

Our visit reveals a meat-rich showcase, reflecting the abundance of farmable meat in Czech Republic, but also demonstrating how the nation has influenced and been influenced by surrounding countries. The couple enjoys confounding expectations—demonstrating, for instance, that their nation has a prodigious wine production industry, in addition to its more well-known beer industry. Also, the revelation that many of the cakes and pastries popular across central Europe originated from Czechia often sparks a fun debate.

But it’s not all about fine dining. Secka’s search for the elusive British soul also takes him to England’s football terraces and pubs with the timeless pleasures of fish and chips alongside a pint or two of real ale.

Estonia: in tune with the land, and each other

Lunch with Her Excellency Ambassador Tiina Intelmann, the head of her country’s mission in London from 2017 to 2021, at the Estonian embassy in Queen’s Gate Terrace, South Kensington, reveals a cuisine deliberately in sync with nature and the seasons. In summer and spring, Estonians tend to eat everything fresh—berries, herbs, vegetables, and everything else that comes straight from the garden. Hunting and fishing remain very common pastimes. Fermented foods, preserved for the colder months, and probiotic ingredients feature strongly, along with vast quantities of sour cream—a constant in the Estonian diet.

Our meal at this stunningly designed embassy, in the company of such a profoundly well-traveled and worldly host (Ambassador Intelmann has previously held posts with the United Nations in Israel and Liberia), seems to encapsulate an innately diplomatic metaphor. That human life, nature and culinary culture can coexist so sympathetically is a valuable lesson for wider cooperation and better relationships everywhere.

Moreover, while Estonia represents a relatively small diaspora in London, their diplomatic mission is a trailblazer for a distinctive style of architecture, design features and guest experience, down to the Estonian birdsong piped into its toilets. It’s no surprise the location regularly features as a listing in the annual Open House Festival.

South Africa: opening hearts and minds over dinner

That Her Excellency Nomatemba Tambo lays the table herself to accommodate an unexpected guest during lunch is a small but revealing insight into the South African approach to hospitality. After all, the sharing of food is core to the South African national identity. It is believed that when South Africa mediated between two conflicting parties, it broke the stalemate with a braai, followed by some robust movements to hypnotic South African melodies.

“I think being an excellent host is about genuineness,” she says. “I believe South Africans are truly amongst the most hospitable people you will ever meet. They will almost never just say ‘Hello.’ They will always follow a greeting with ‘How are you?’ And guess what? They really care.”

Over lunch at the embassy in Trafalgar Square, the sense of putting your guests first, of placing them at the heart of why you are doing what you are doing, comes across strongly. The menu brings alive the commodities, natural resources and geography of the country, from seafood to spices and, of course, its wines—one of its biggest exports. But above all, it’s the gesture of opening up your table and yourself to your guests that seems to be the open secret of the embassy’s mission.

Kazakhstan: at the crossroads of people and cultures

An invitation to dinner with His Excellency Erlan Idrissov at Kazakhstan’s embassy on Pall Mall reveals how acutely the nation feels its place at the heart of Eurasia, and how that impacts its food, drink and perspective on global relations. The country’s a mix of cultures, religions, traditions and more than 130 ethnicities; and has been influenced by Russian, Uzbek, Korean, German and many other culinary cultures.

Menus at official dining occasions reflect that mix of cultures, and nomadic culinary staples of lamb and horse meat are updated with obvious diplomatic intent. “People from other parts of the world may feel squeamish that we love horse meat, but similarly, sometimes we also take some eating habits—including here in the UK—as strange and unusual,” says Idrissov. “We tend to search for a balance between our culinary habits.”

In practice, besbarmaq, traditionally consisting of boiled horse meat, is made in London with beef or mutton; while quyrdaq, a roasted meat dish traditionally prepared in a lamb stomach, is served in a large pumpkin. More authentic staples from Kazakhstan include its most famous chocolate brand, Rakhat, whose wrapping appropriately mimics the colors of the Kazakh national flag.

“Cuisine is a tool for a country to present itself, to highlight its cultural identity,” Idrissov tells us. “It is especially true for a young nation like ours—not many people can even locate Kazakhstan on the map, let alone name its traditional dishes. But most importantly, we build bridges of friendship and mutual understanding. There is a famous Kazakh expression that goes ‘When the cannons talk, the diplomats must be silent.’ Our task is to make sure the cannons do not start talking.”

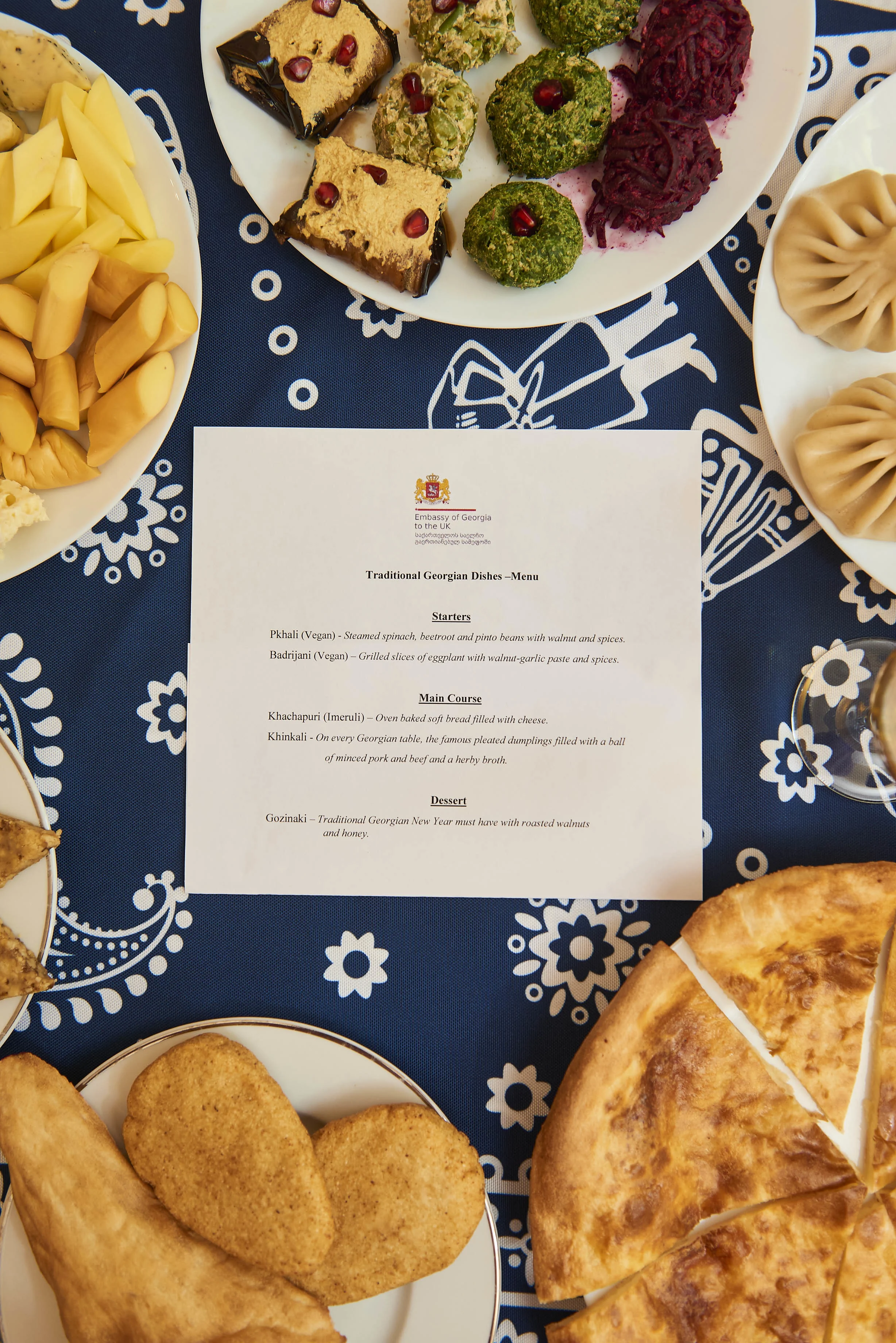

Georgia: wine and national identity, entwined

Since entering her role as Georgian Ambassador to the UK in April 2020, Her Excellency Sophie Katsarava has seen the country’s wine exports to Britain increase by over 150% and growing. This may be a consequence of increased alcohol consumption during lockdown and burgeoning interest in natural wines. But we suspect it could also be due to her passion for promoting it as part of her diplomatic mission.

Georgia is one of the oldest wine-producing countries in the world, and its traditions have been recognized by UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list. Its moderate climate and Black Sea-moistened air provide fine conditions for vine cultivation. In some places, the soil in vineyards has been so intensively cultivated that grape vines grow up the trunks of fruit trees. The grapes eventually hang down among the trees’ fruit as they collectively ripen—a method of cultivation called maglari.

But Georgian wine remains contentious, falling victim to political tensions with Russia, counterfeiting problems and mislabelling. Today, Katsarava proudly serves it during official functions, setting the record straight, correcting preconceptions and winning new respect for the country and its vinous output over a taster.

Colombia: sustainability made tangible—and tasty

The dining table at the Colombian embassy in London has become something of a shop window that brings to life just how delicious gains in more sustainable approaches to agriculture and nature can be.

It’s a clear mandate for a diplomatic gastronomy strategy that adorns menus with plentiful seafood, coffee and fresh fruit, all of which contribute directly and indirectly to protecting Colombia’s forests and coastlines, and the richness of their fauna and flora; as well as preserving its indigenous cultures. “Our gastronomic approach safeguards the ingredients and traditions of our country," says His Excellency Antonio José Ardila, the country’s former ambassador to the UK.

In diplomatic circles, this is a win-win, particularly given the fact that combating climate change and protecting biodiversity are among the cornerstones of the bilateral relationships between Colombia and the UK. More than that, a strategic push towards sustainable agriculture is not only ecologically responsible, but also helps build more positive associations of a country that has experienced decades of negative effects as a result of the drug trade.

Bangladesh: food does the ‘diplomatic heavy lifting’

An estimated 80% of the 12,000 Indian restaurants in the UK are, in fact, Bangladeshi in origin, so you’d be forgiven for thinking that the two countries’ culinary cultures are well entwined. But the overflowing table hosted by Her Excellency Saida Muna Tasneem at the Bangladesh High Commission in Queen’s Gate, London, acts as an eloquent testament to the astonishing range and nuance of her country’s gastronomic heritage.

Tasneem—the High Commissioner for Bangladesh to the UK, as well as Ambassador to Ireland and Liberia, and Permanent Representative of Bangladesh to the IMO—is a revered figure in London’s diplomatic circles. Among her other activities, she acts informally on behalf of an alliance of female diplomats advocating for women in the developing world. In all her roles, food plays a vital function. Whether she is in Brick Lane’s curry houses, in the capital’s finest hotels, or at the High Commission itself, she addresses the wide array of causes dear to her heart over fragrant plates of her country’s renowned food.

Identifying red chilies, turmeric, cumin, coriander and rice as the staples of Bangladeshi food, Tasneem states that these ingredients “run through our blood.” Also, she goes on, it is said that Bangladeshis cannot survive on foreign food after three days away from home.

Sri Lanka: a celebration of competing culinary cultures

As a sign of how seriously the Sri Lankan High Commissioner to the UK takes the role of the dining table in diplomatic life, it would be difficult to beat the fact that Her Excellency Saroja Sirisena personally wrote and planned the entire menu herself.

Sri Lanka’s culinary heritage reflects a complex colonial history, with many ingredients and flavors from Portuguese, Dutch and British imperial days still influencing diets and tastes. Today, the island’s reputation as a producer of fine tea pervades (it’s one of its biggest exports), and spices (chief among them cinnamon), coconut, and fish also feature strongly.

That innate ability to integrate different flavors, and the power of food to draw people together is clearly celebrated by an ambassador, who has herself carved out a career in the contrasting cultures of India, France and Belgium, and within UNESCO, following education in Australia and France.

Costa Rica: rich flavors, changing priorities

With Costa Rican cuisine having already merged its indigenous flavors with Spanish, African and other colonial influences, it’s no surprise that His Excellency Rafael Ortiz Fábrega enthusiastically took up his position as the country’s ambassador to the UK—no doubt with the prospect of experiencing delicious new flavors in the melting pot that is London.

Prior to being a diplomat, he arguably got an early taste for how food and drink—or at least soft drinks—can wield soft power across the world after serving for more than previous role as General Counsel, Central America and the Caribbean Division for Coca-Cola.

Today, he uses the power of his diplomatic dining table to target different priorities. The country’s food and drink brings to life a new era of ecotourism; and its sustainable practices highlight the challenges of mitigating the effects of climate change, and making the Costa Rican economy net zero in carbon emissions by 2050.

Denmark: a gastronomic reputation to maintain

If Danish cuisine once followed the trajectory of its fellow Nordic countries, its diplomats now have the mantle of New Danish cuisine to live up to. This is a world in which acclaimed, Michelin-starred Danish chefs and restaurants routinely take the top spots of global rankings. (Copenhagen restaurants Noma and Geranium took first and second spots respectively in the 2021 World's 50 Best Restaurant Awards.)

Against that context, you’d think Denmark’s former ambassador to the UK, His Excellency Lars Thuesen, had his work cut out for him. In fact, with the Danish embassy being the first purpose-built mission in central London (it dates back to 1977), it seems as if the country has been conscious of using food as a soft diplomatic power for some time. Ambassador Thuesen calculates that some 50,000 guests have eaten around the table in its very Danish-designed dining room.

While the ambassador is casual, gregarious and relaxed as a host, the dining room etiquette is formal, with careful attention given to the color of flowers, seating arrangements and the order of toasts. It's perhaps no surprise that light-hearted beer nationalism is practiced, with Tuborg and Carlsberg a staple of the fridge.

Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office: British hospitality on a global scale

The FCDO plays a key role in showcasing UK cuisine and the icons of British food in British Embassies and High Commissions around the world—everything from Scottish smoked salmon to English sparkling wines, Welsh Lamb and Northern Irish beef. After all, this is an export industry worth £23 billion.

Recent on-the-ground examples of such soft power include Stephen Hickey, Ambassador to Iraq, baking local bread and preparing Iraqi dishes during social media cook-alongs in Arabic; and former Prime Minister Boris Johnson gifting hampers packed full of clotted cream biscuits and Cornish sea salt to international partners ahead of the G7 Summit in Cornwall in June 2021. Witness the fusions of British classics with local culture, such as “le Lancashire ‘otpot canapés” served at the British Embassy in Paris, or the low-carbon vegan lunch hosted by the Ambassador to Belgium. This year, British Ambassadors and High Commissioners representing the UK around the world have nominated 70 of their favourite recipes to a special “Platinum Jubilee Cookbook” celebrating British food and drink products.

For Nigel Adams, the former Minister of State with responsibilities for Asia, it’s clear that this approach is just as relevant today as it has been historically. “This isn’t just about fine dining clichés at the most prestigious posts, but the power that food and drink has as a universal language in helping us build bridges with international partners” he says.

Thank you

Bompas & Parr and WePresent are grateful to the Ambassadors, High Commissioners, diplomatic and embassy staff who facilitated, curated and prepared the meals and interviews for this article. In addition to Louisa St. Pierre; MA+ Group, Raushan Ussenova; Diplomatic Spouse Club London, Venitia van Kuffler; Editor DIPLOMAT Magazine, Angela Bourderyemunoz; Canning House, Straun Stevenson; former Member of the European Parliament, author and columnist, Charlie Surbey; photographer, Joe Almond; videographer, Kitty Slydell-Cooper; St. John Restaurant London.