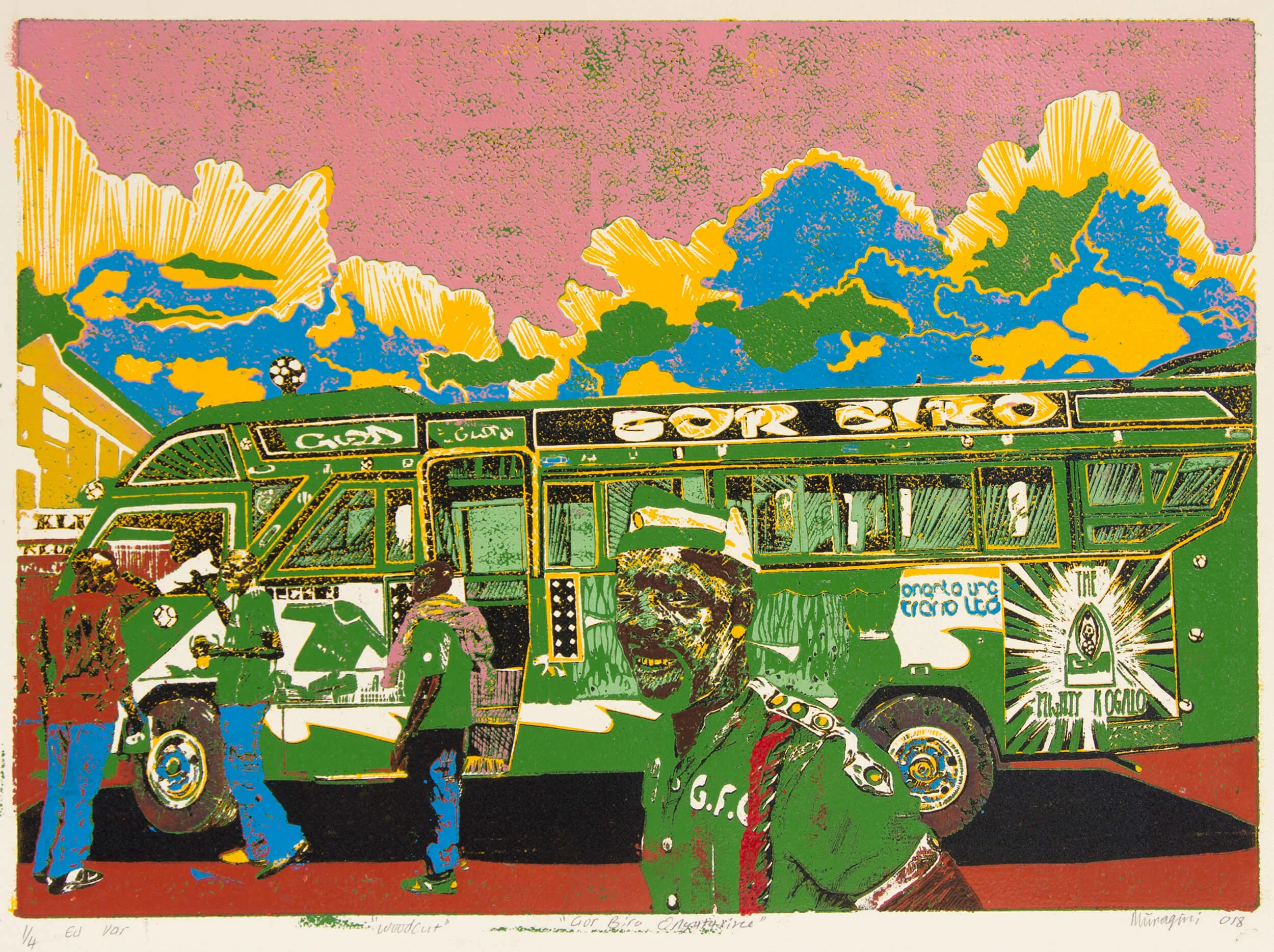

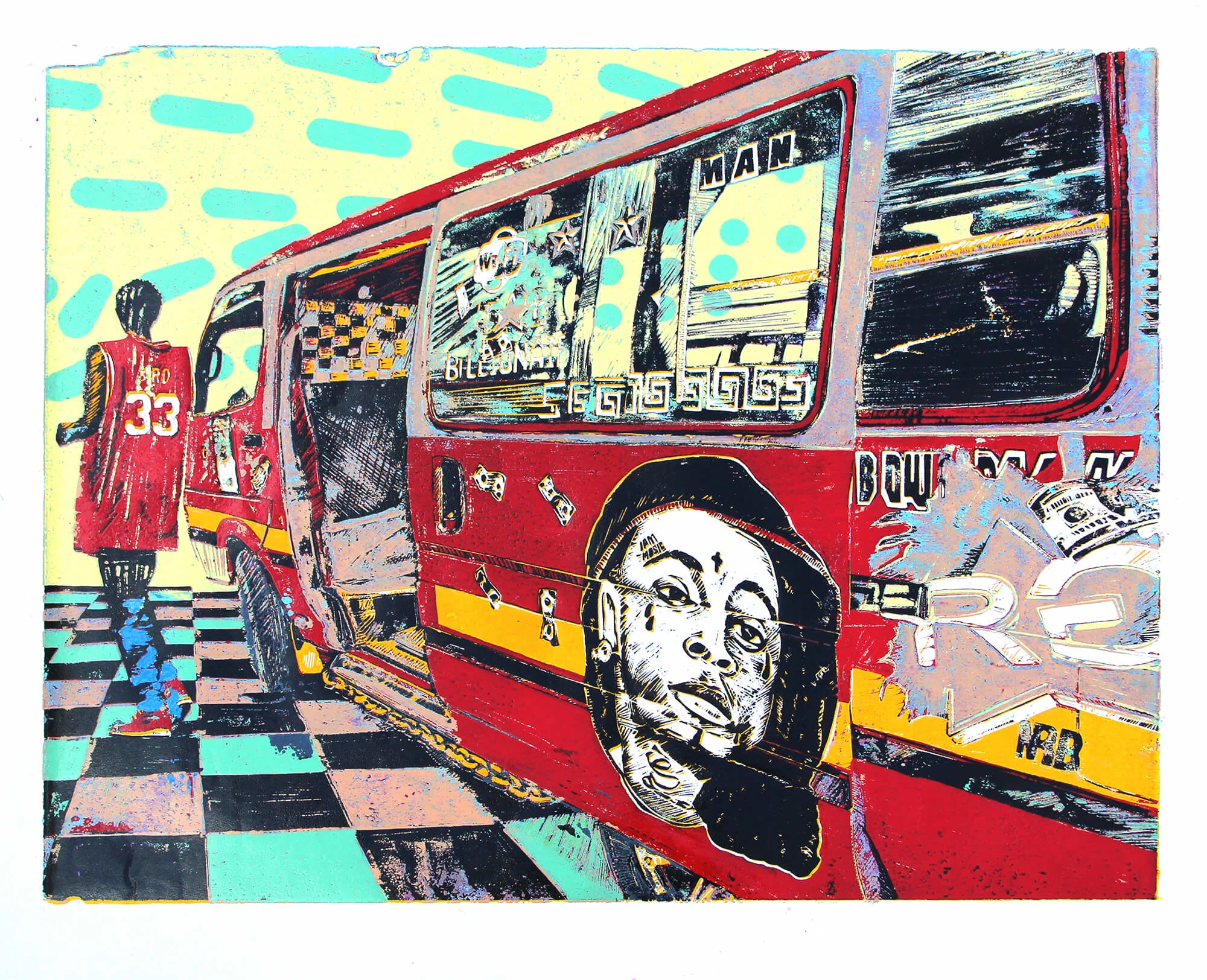

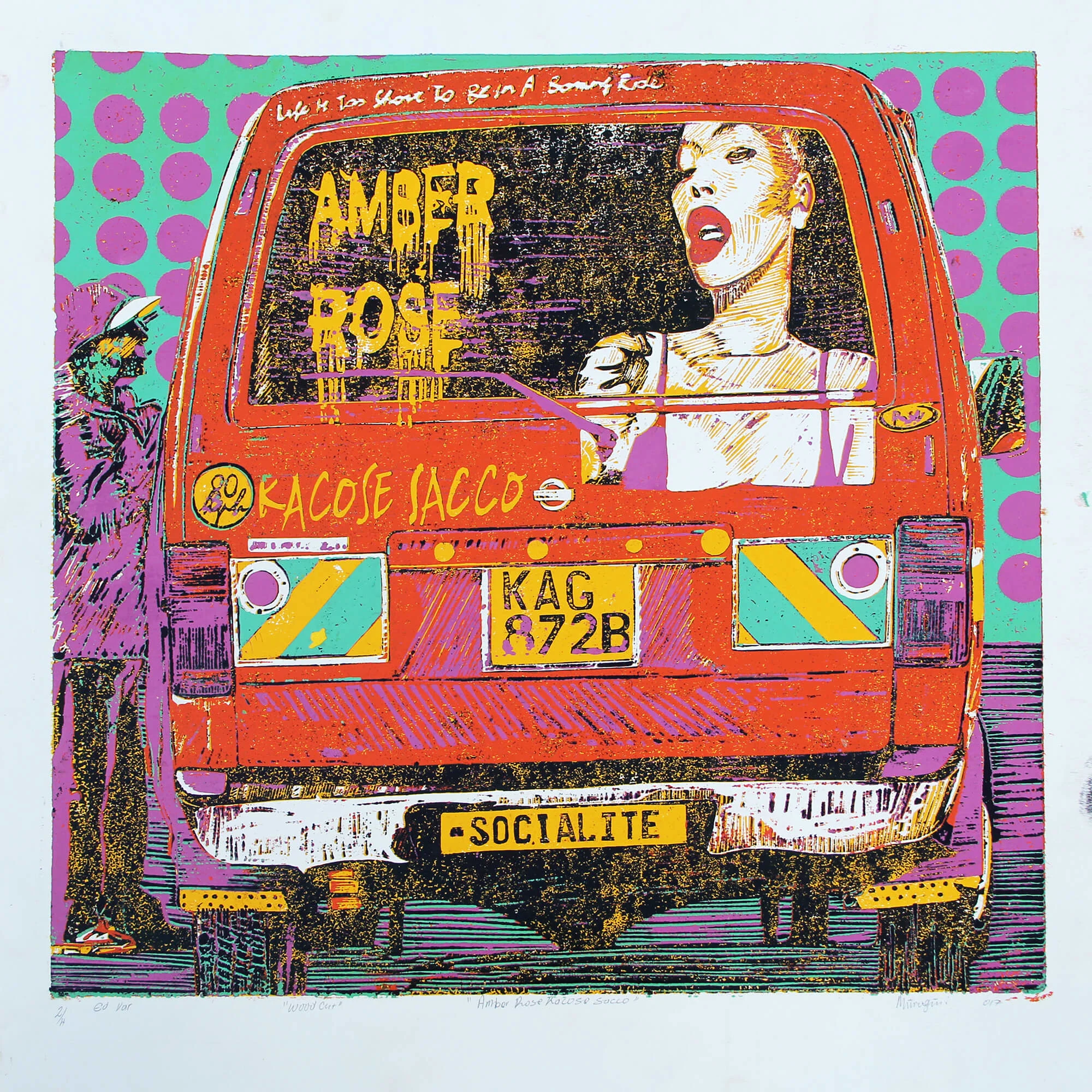

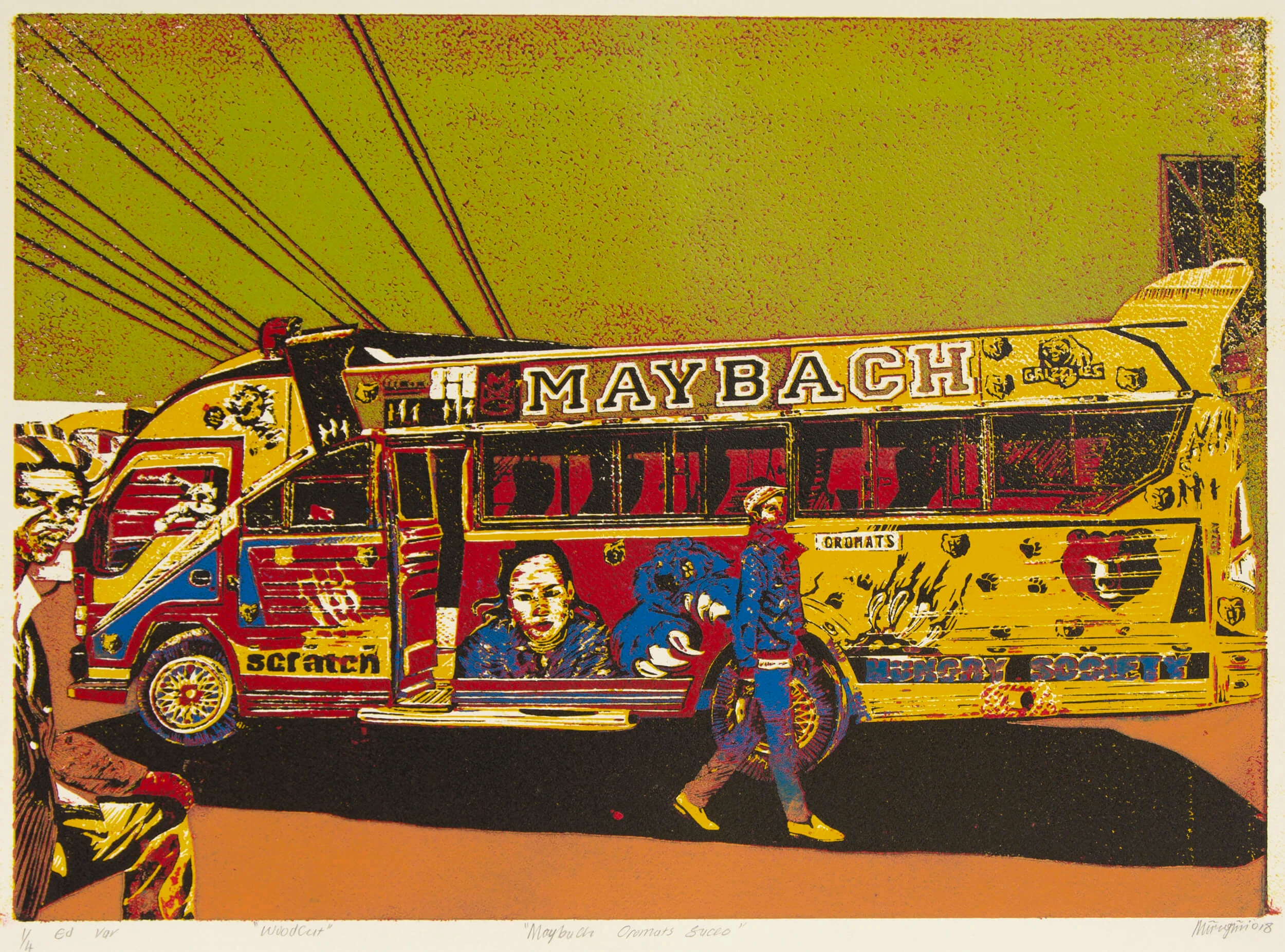

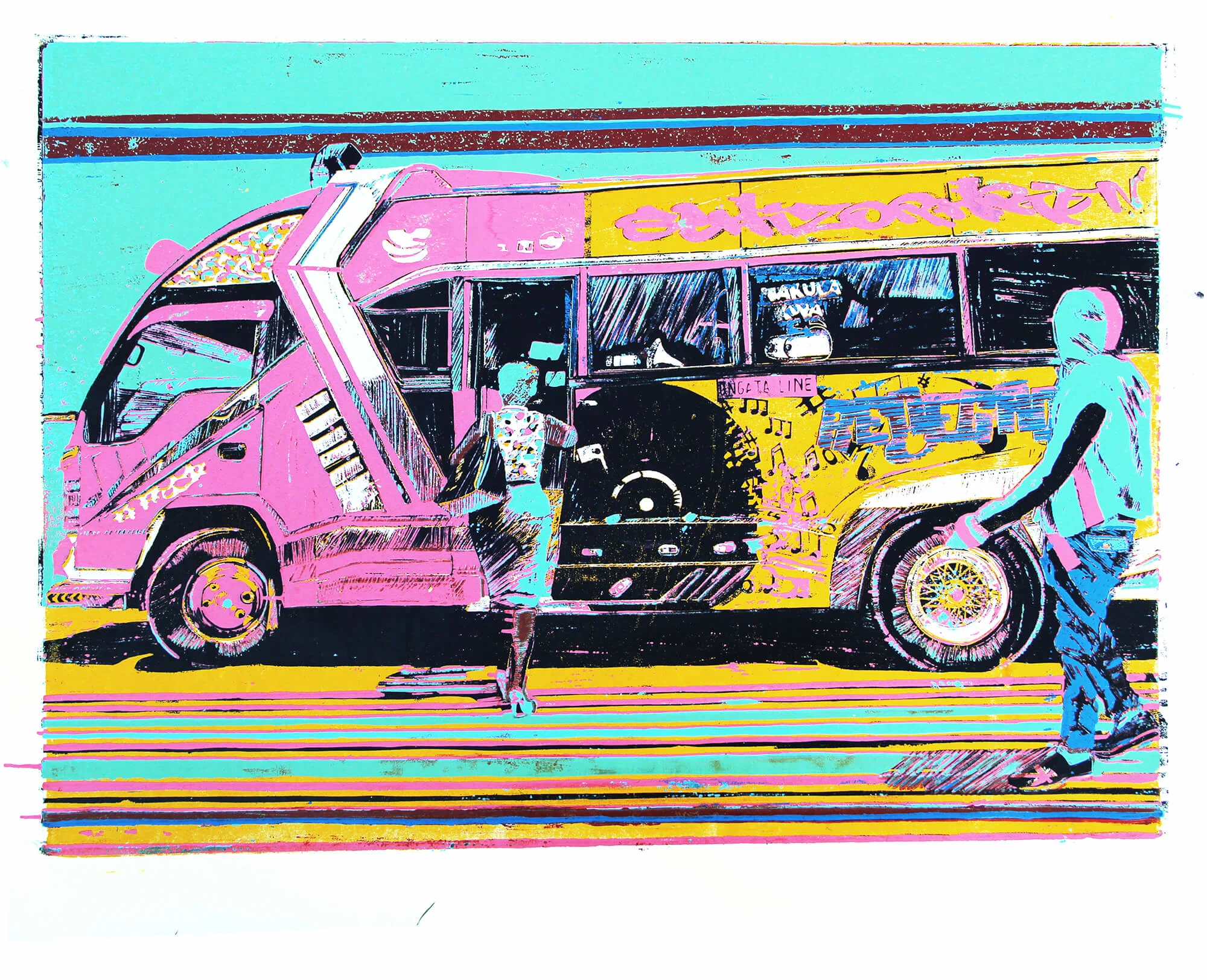

Dennis Muraguri’s portfolio of woodcut prints is a varied and vibrant collection of scenes from Kenya’s bustling streets. The main common denominator between them? Almost all of them contain a matatu (beautifully-painted minibus taxis that zoom around the roads blaring music, and act as Dennis’ main inspiration.) He walks writer Alix-Rose Cowie through his printing process, and explains why he’s always been captivated by matatus, and how important they are to life in Kenya.

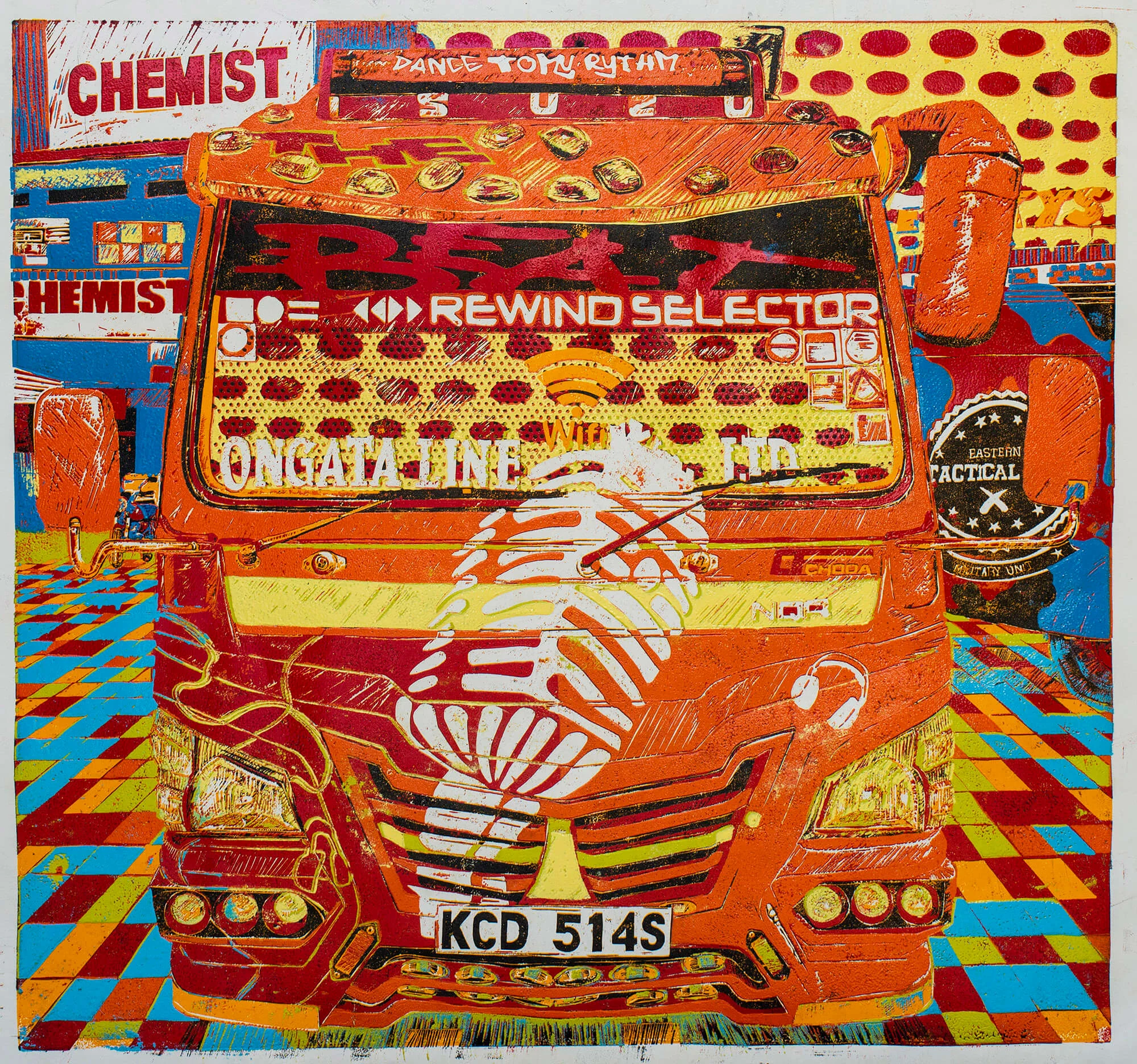

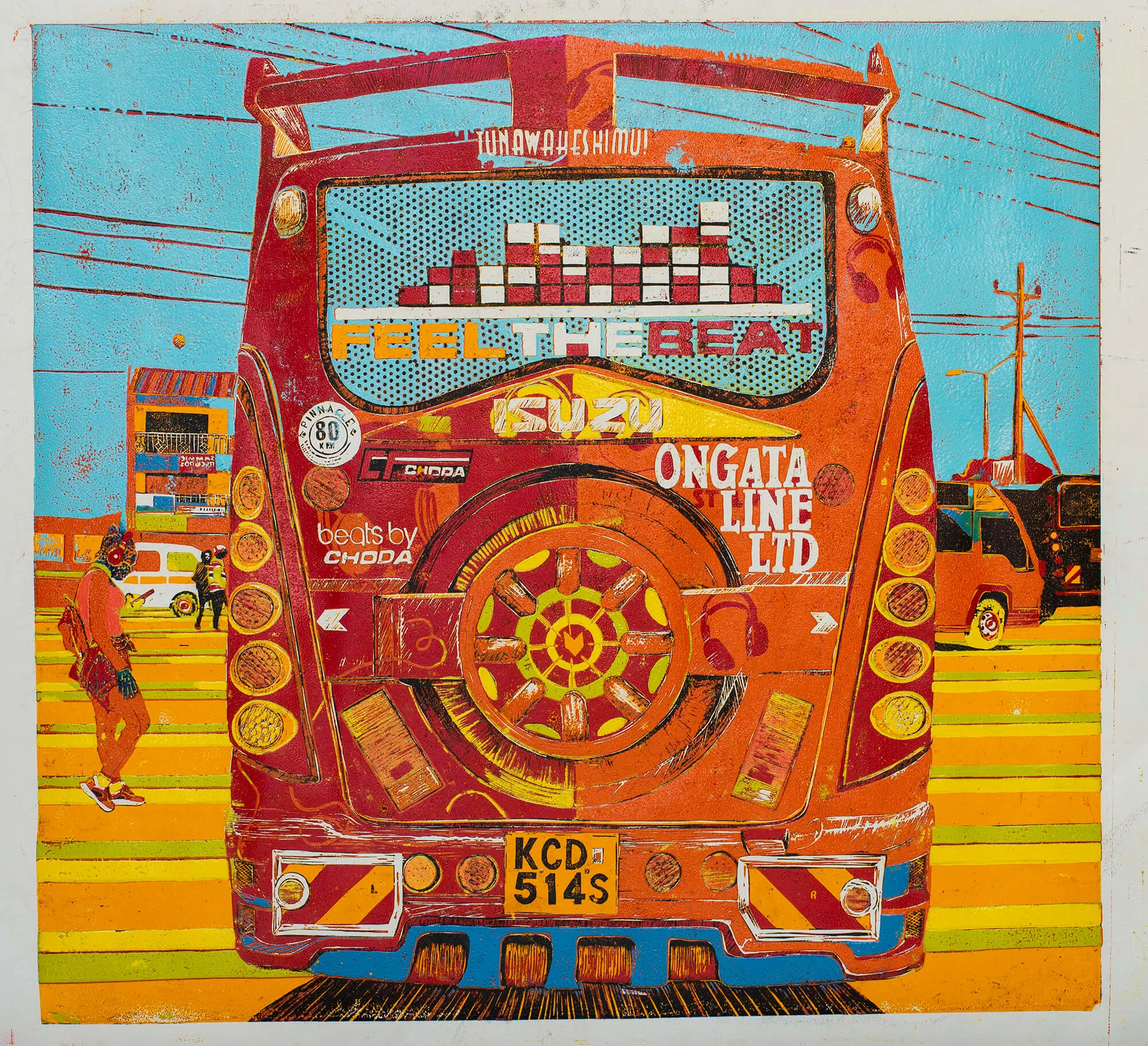

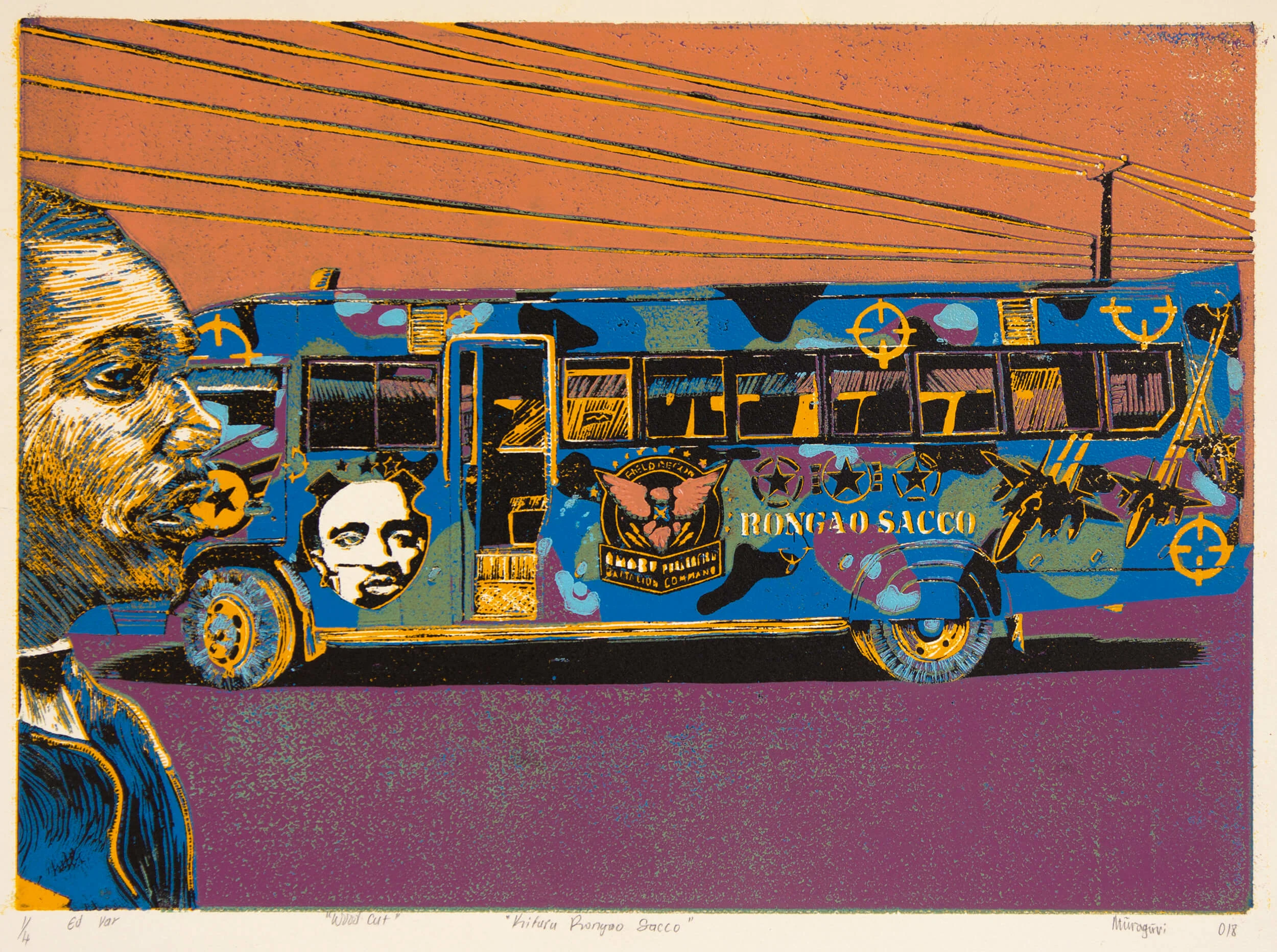

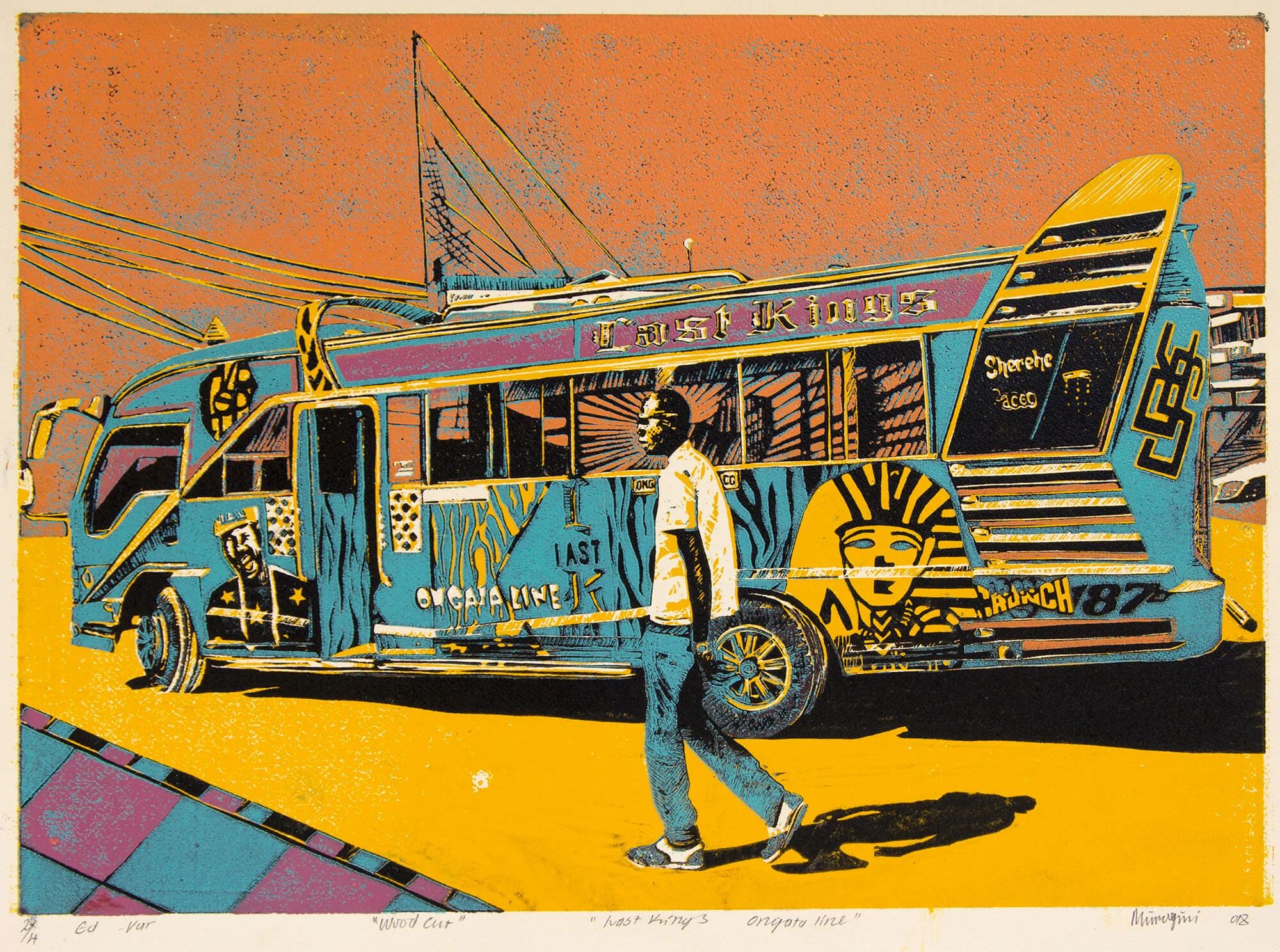

To talk about Kenyan artist Dennis Muraguri’s work is to learn about matatus. The dominant mode of transport, matatus are minibus taxis, painted in flaming colors and emblazoned with slogans and artwork, that flout the rules of the road to get commuters to and from their daily destinations as quickly as possible, usually to a blasting soundtrack of hip hop or reggae. Also a sculptor and a painter, Dennis’ most eye-catching work is undoubtedly his woodcut prints of matatus. The printmaking techniques used on the vehicles themselves—stencils and stickers—inspired him to use woodcut printing to best translate their flat graphics. He also finds the time-consuming process of gouging his design out of the wood block to be therapeutic. When he’s in the right mood, sleep becomes the enemy and he can keep going for hours.

Dennis grew up in a town called Naivasha, in an apartment block that overlooked a matatu park, and he would sit in the window and watch the vehicles come and go. “They’re very fun to watch,” he remembers. “There's always drama happening where matatus are.” When he was 14, the family moved to the capital Nairobi where the matatus were next level; bolder and brighter. “Being a village boy, that intrigued me,” he says.

After high school, a rebellious Dennis became a nuisance to his mother, who wanted him out of the house. When she asked what he wanted to do, he offered something he thought she’d never go for: studying art. It backfired when she told him to start looking for an art school. While at the time he didn’t want to go to college, art had always come easy to him. It’s what he’d be doing in his textbooks instead of listening in lessons at school. “When it came to art, I didn't need anybody to push me to do it,” he says. “It felt like cheating when I was allowed to go to school for art. Creating isn’t a struggle for me. I can have problems in life, but not problems creating.” He graduated from Buru Buru Institute of Fine Arts.

Creating isn’t a struggle for me. I can have problems in life, but not problems creating.

In college there was a sort of game that Dennis got into when traveling around the city where he and his peers would wait to catch the best matatu (the most beautiful ones are called manyangas.) All the matatu-watching became a career making art out of the art he sees zooming past on the roads. In Nairobi, where Dennis still lives and works, you’ll step outside and immediately see a matatu, so his subject matter is never difficult to come by. Dennis walks around with a point-and-shoot camera and takes photos of the scenes that interest him. His compositions include people coming and going, getting on or off or walking past in a hurry in the foreground. “My thinking is that without the people around, it's just a bus. But with the people, it becomes a matatu.” Sometimes the bustling scene won’t translate through a still photograph, so he adds a patterned, color-clashing background to make it feel more noisy.

Before he starts drawing the scene onto the woodblock, Dennis flips the photo in Photoshop so he can draw the scene—text included—in reverse. When he peels the paper from the block, the work has been printed the right way around. “I enjoy the process,” he says. “The fun part is that you never know what you'll end up with. You can imagine what you want, but only once you roll the ink and then pull the paper, you get the full revelation of what you just did.”

One of Dennis’ prints reads “Matatu for President: Manyanga, Music, Mischief & Mayhem.” He made it as a satirical statement on local politics during a national election in Kenya. As Dennis explains, matatus will get you where you’re going very fast but are notorious for breaking traffic laws in the process. It’s efficient if you’re riding in one but the driver’s not getting you to your destination quickly so that you’re not late; they’re doing it so they can squeeze in more trips to make more money.

“I will choose that matatu as my representative because they will do whatever they have to do to get me there. As long as I'm inside, I'm catered for. The problem is, it’s at the expense of other people also using the road. I see that as a very good representation of the political situation,” he says.

In relation to the arts in Kenya, Dennis says there’s no big support from the government. “There’s no real system and it’s not institutionalized in any way. All of us artists are free agents. We operate on self-belief,” he says. But art has always been a vibrant part of the culture and it only takes a matatu to drive by to see it.

The artwork on matatus makes Dennis’ art possible. Though he works as a professional artist and has exhibited globally, he believes it would be an insult to matatu artists to think he could paint one. “They're the ones who inspire me. They do it better than I could ever do. It's communication. It's a reflection of what's happening in the world and locally.” Painting American movie stars or European football teams, Matatu artists are on the pulse of global pop culture. “They say,” Dennis adds, “that if you're not on a matatu, you’re not famous enough.”