Bristol-based artist Darcy Whent grew up in rural Wales, in circumstances that demanded resilience long before adulthood arrived. Now, she transforms those early experiences into paintings and drawings that grapple with what it means to have to grow up too soon. She tells Alix-Rose Cowie about survival, transformation and how, for her, making art is a way of sitting with and processing what cannot be easily spoken.

Bristol-based artist Darcy Whent was born and brought up in rural Wales: “In a valley with nothing around it apart from sheep, horses and dogs,” she says. “All I wanted was to be a city girl but I was brought up in poverty and I felt so much resentment for it.” She feels differently as an adult, tenderly bringing tokens of her Welsh ancestry into her work, like the carved wooden love spoon in her drawing “This is not a silver spoon and I won’t be fed by one either.” “When I was little, probably all I wanted was to be fed by that silver spoon,” she says, “and now I couldn't think of anything worse because I don’t know what sort of person I would be.”

When I’m making something tangible, it always feels stronger than the memories that I have.

In secondary school, painting became Whent’s outlet for the feelings she struggled to express elsewhere. At home, she and her two sisters assumed the shifting role of “mother” when their mother’s mental health disorder became all-consuming. The studio remains the only place she can sit comfortably in silence with her thoughts as she paints on canvases bigger than herself. “It brings up things that I didn’t know were there before,” she says about art as a physical means to process her life. “When I’m making something tangible, it always feels stronger than the memories that I have. It’s almost like putting a nice cold pack on something that might be burning.”

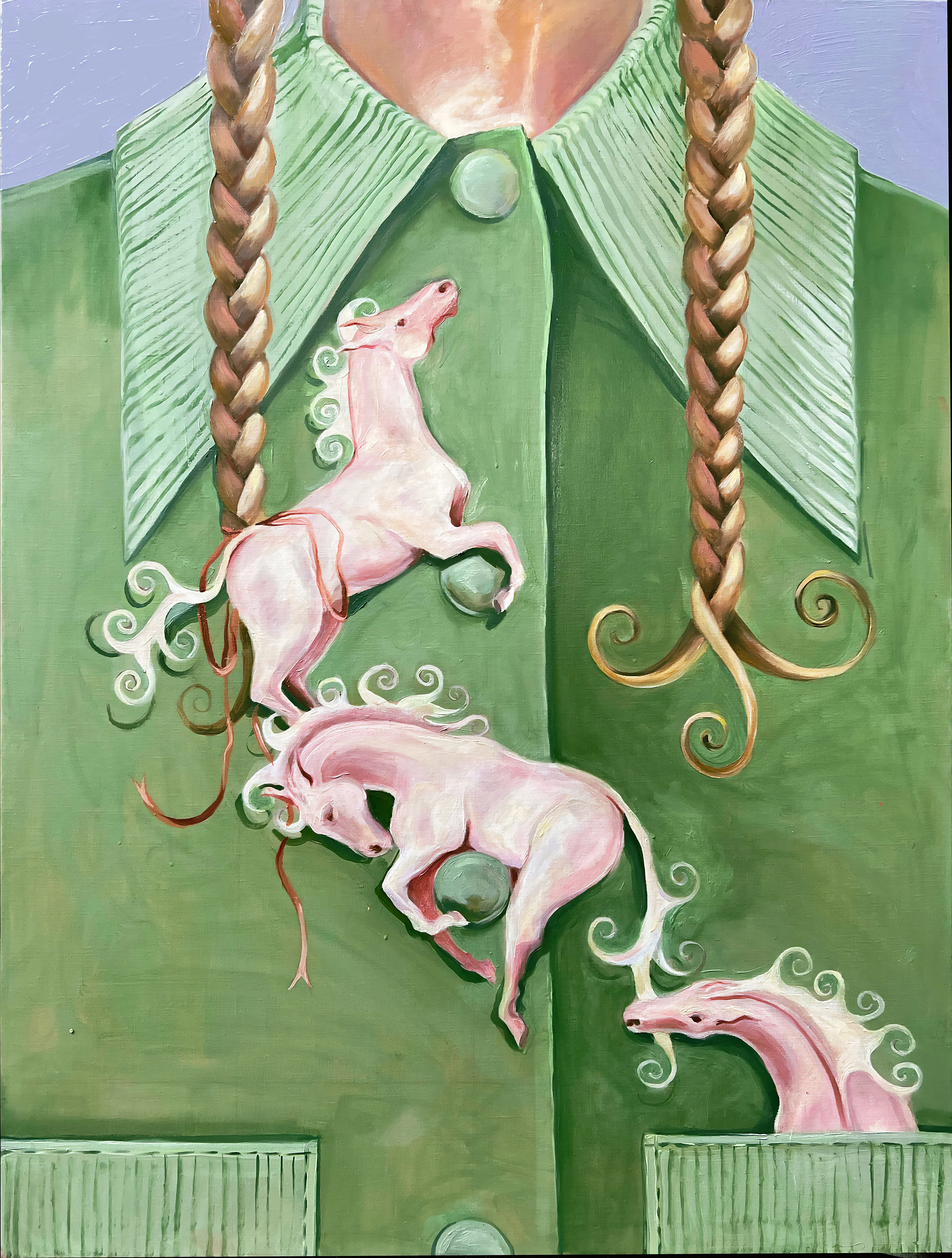

Whent’s recent art stems from the acutely experienced yet impossible to pinpoint stage in a woman’s life between girlhood and womanhood; a twisting and unfurling becoming visualized in the coils, spirals and creeping vines in her works. Her subjects are caught in this in-between. “They’ve got full on bushes and big tits, but in reality, they still feel quite babydoll because ultimately that’s how I feel. I felt like I was forced to be this woman, but in reality, I was still this little dumpling,” she says of her teens. Her body of work “Becoming Feral” explores “the feral instinct that emerges when childhood is stripped away too soon.”

I felt like I was forced to be this woman, but in reality, I was still this little dumpling.

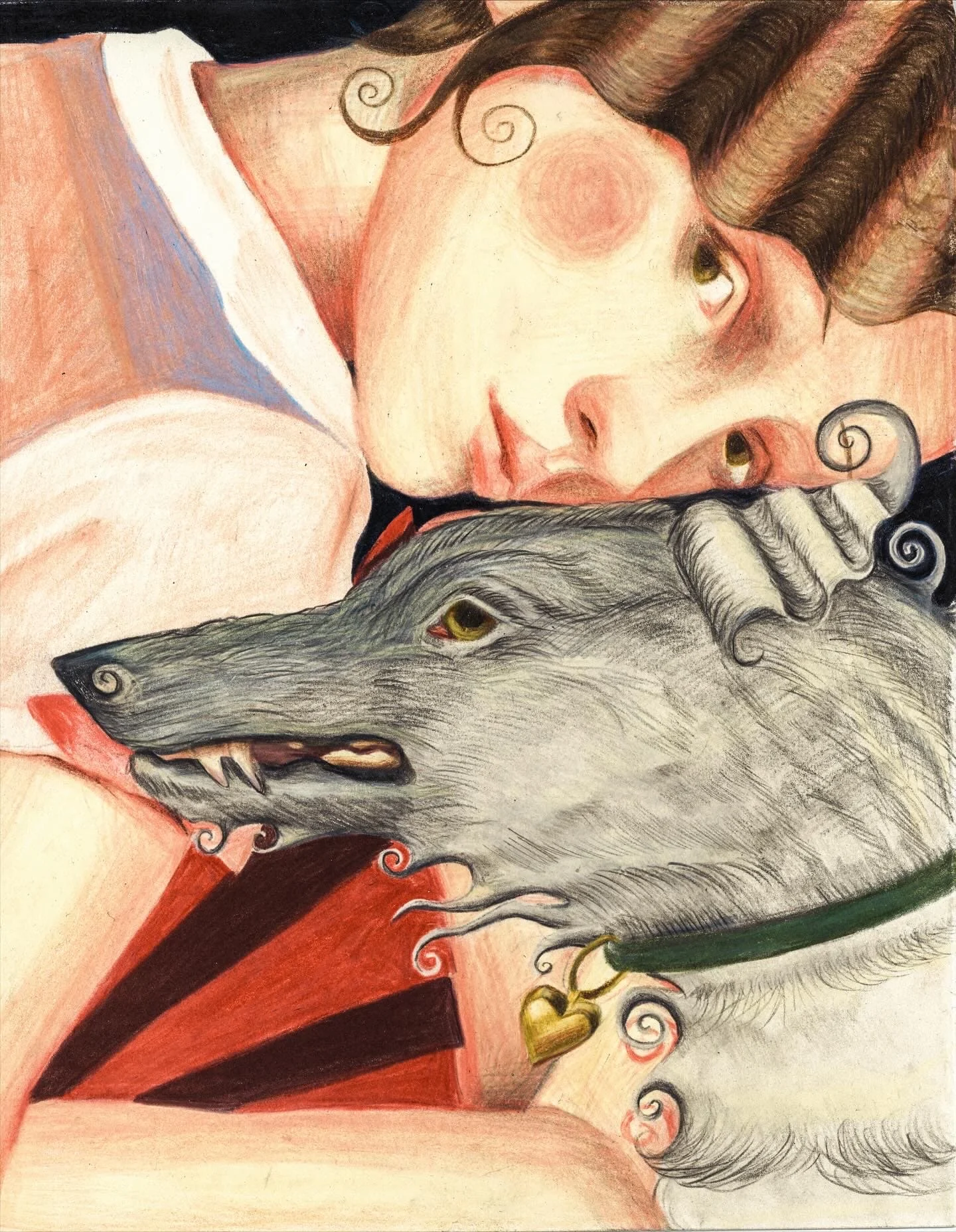

“Feral” isn’t a negative word for Whent. “It just means you’re not going in the way that people expect; you’re doing everything to survive the circumstances that you’ve been given,” she explains. She sees women as powerful, wild dogs. “And I mean that as the biggest compliment.” Seeing Paula Rego’s series of dog women had a huge impact on her, and she remembers thinking, “Yeah, I completely get it,” and feeling the urge to elaborate on the motif for herself.

By developing a symbolic visual language for her experiences, Whent reforms them, turning true life into a coiffed but discomfiting fantastical fiction of ribbons, hooves, fur, plaits, tongues, serpents and frills. She’s inspired by how the remembering of a memory changes it, and the sudden vertigo of seeing a familiar situation from a different perspective. Her reinterpretations are largely set in an enclosed space, sometimes flanked by stage curtains, with no windows or doors. Looking back, her childhood experience would remain normal as long as it played out within the same walls, it was only in contrast with outsiders’ experiences that hers became bittered. She wants to express this disorientation in her work, using sugary colors to evoke the queasiness of eating too much pudding.

A lot of my paintings and my drawings include that sense of longing for things that I can’t attain, and also the things that I have and I fear.

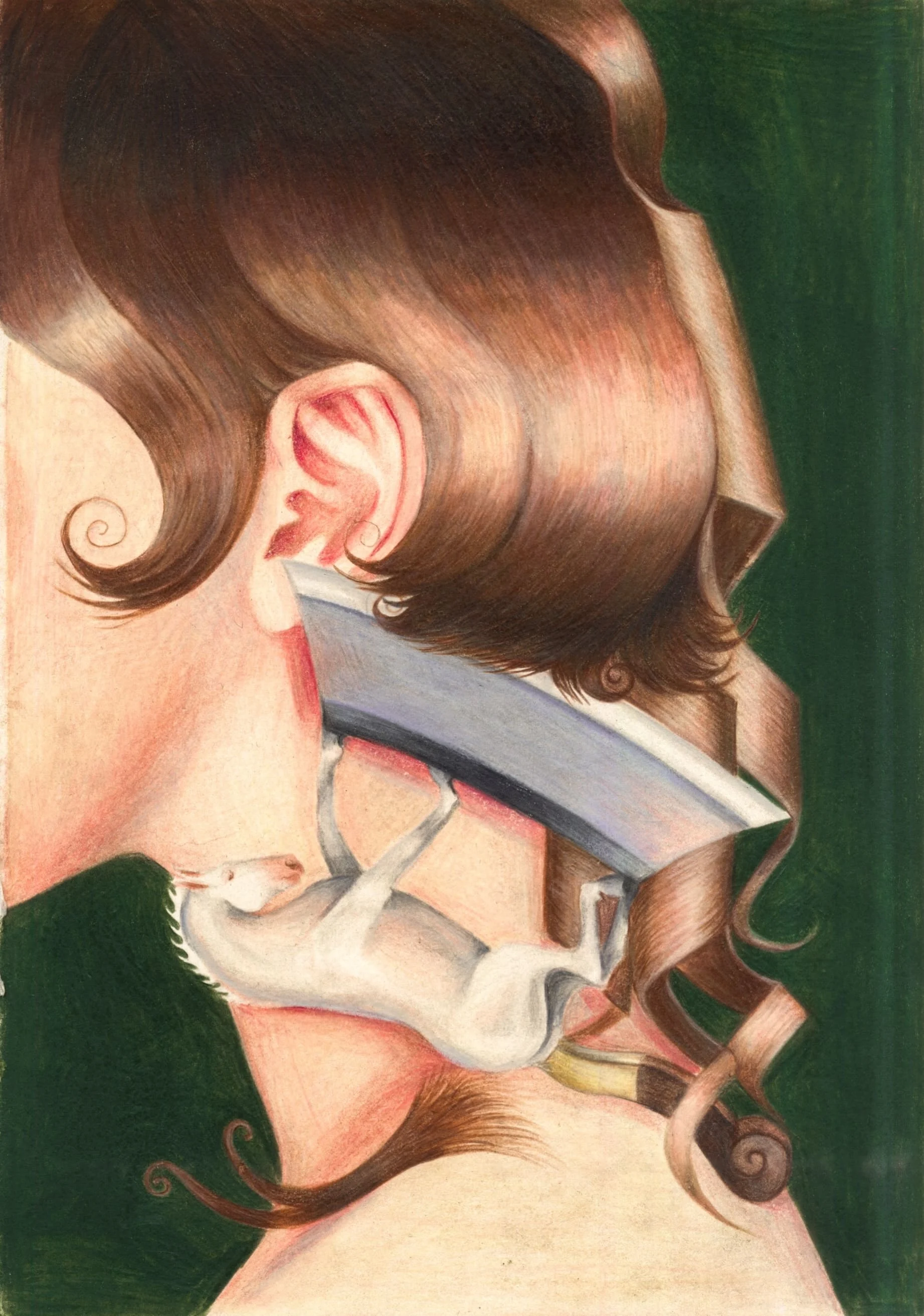

Horses abound in Whent’s work; in the patterned imprint of a lace bra on skin, or two horse heads mirrored in the flesh of an apple. Interrogating her fascination with horses while studying Fine Art at Bath Spa University, she came to a realization: As a child she’d wanted parents who were like race horses, blinkered and laser-focussed on their goal, being their children. “Whereas in my experience, my mother in particular was more like those horses that you see in national parks where you are not meant to interfere with them,” she says, but instead appreciate their beauty and respect their wildness. In her pencil drawing “No longer small,” a horse blade chops off a girl’s childish ringlets.

Hair—an inherited trait which can become tangled or be tamed—is a broader symbol in Whent’s work for encountering and coming to terms with her fear of recurring generational trauma. “As much as I want it to be in my control,” she says. “A curl in your hair is something that you can’t stop no matter how hard you try—it’s natural.” No matter how many times you brush it into submission or pull a flat iron through it, it will eventually spring back. “I’m also drawing hair that I wish I had. It’s super silky with no coarseness to it,” she says. “A lot of my paintings and my drawings include that sense of longing for things that I can’t attain, and also the things that I have and I fear.” The tension is in this tussle between a feral survival instinct and the deep need to be cared for.