It was the most famous plane in the world – a miracle jet reserved for the rich and famous which inspired, and still inspires, millions more. One of those is Lawrence Azerrad whose obsession with all things Concorde has now become a book, Supersonic, the definitive design celebration of the jet.

Madeleine Morley spoke to him about how and why Concorde captured his soul.

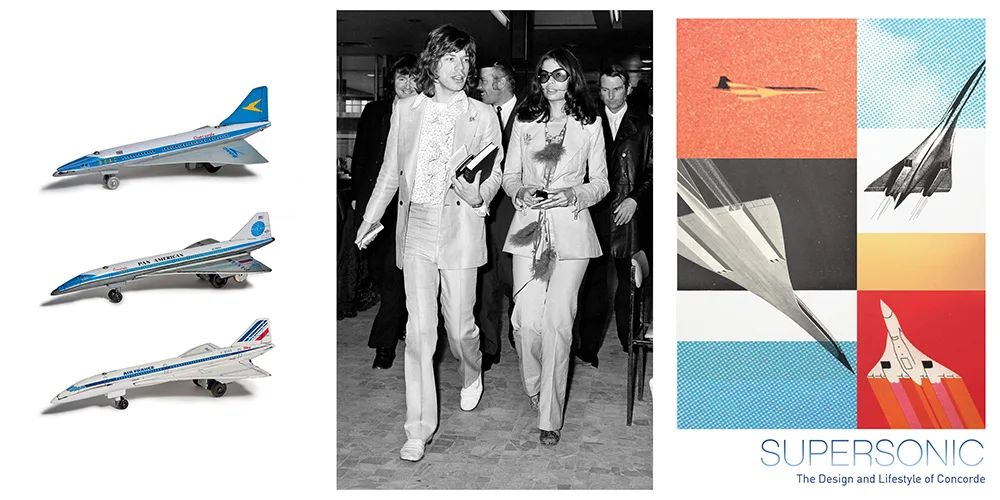

In 1989, Lawrence Azerrad was a teenager assembling a Concorde model kit in his home in Los Angeles. He noticed that each small piece possessed grace, a sense of speed and a space-age sense of cool. Putting the tiny fragments together, he says, “stirred nascent thoughts of becoming a designer someday.”

In November that same year, the first round-the-world flight by British Airways Concorde was completed, covering 28,238 miles at a supersonic speed of 29 hours and 59 minutes. The British-French turbojet-powered passenger airliner would operate until 2003, hurtling the rich and famous across the earth faster than the speed of sound.

“I was probably too old to be playing with craft models at that age, but I think I was just getting familiar with how awesome Concorde was,” Lawrence says. “After all the assembling, gluing, spray painting and decals, it wasn’t the sleekest model, but it lit the spark.”

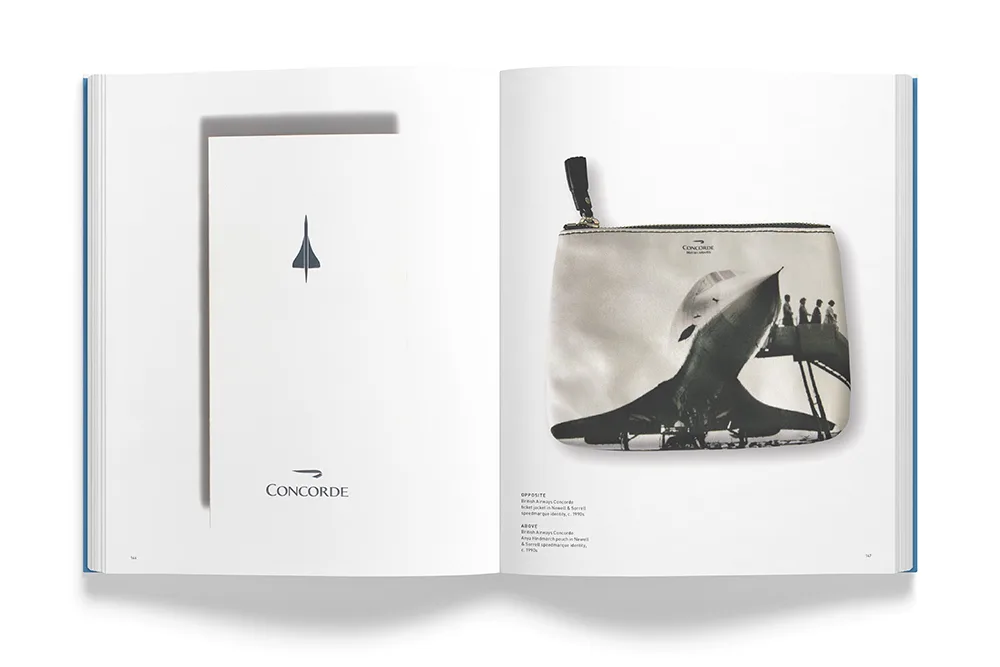

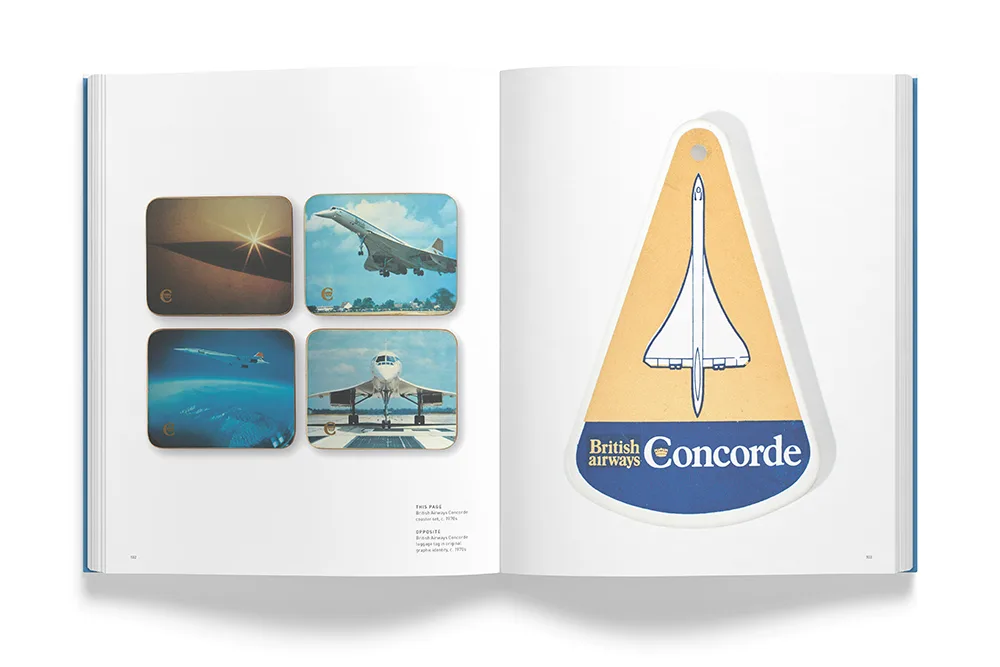

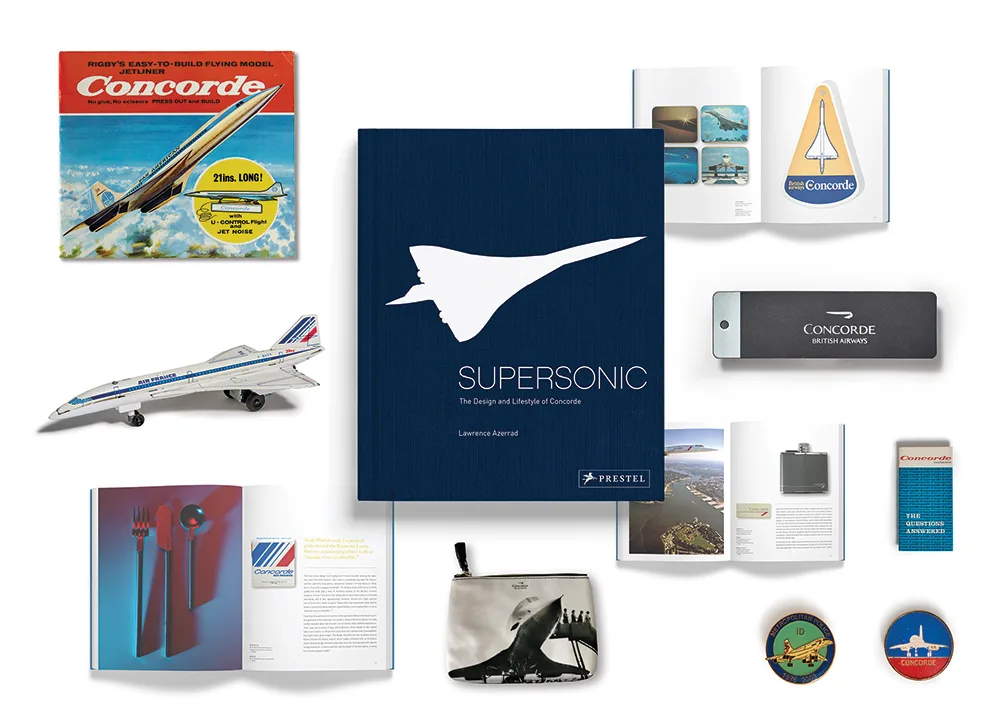

It was the spark of an obsession. Studying graphic design at California College of the Arts in his 20s, Lawrence spent countless hours every week scouring auction pages for Concorde memorabilia, building a collection that now consists of over 700 items.

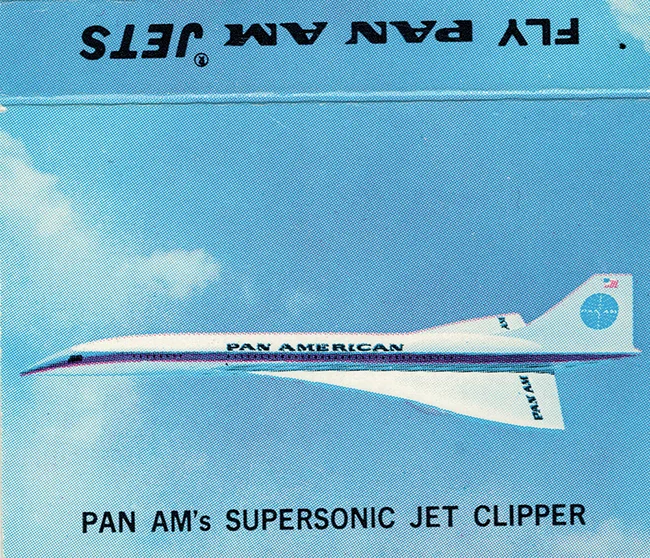

Today these stamps, matchbooks, luggage tags, lighters, thimbles, cutlery, fliers, menus and more – all punctured by the penetrating silhouette of Concorde – fill boxes in the basement of Lawrence’s studio, LADdesign.

The company is known for its identity systems for clients like Sting and The Beach Boys, as well as its Grammy Award-winning work on the Voyager Golden Record reissue. During the years building up his practice, Lawrence has been quietly shaping his mountainous Concorde collection into the form of a book.

Supersonic: The Design and Lifestyle of Concorde will be published this fall by Prestel, a release that chimes with the 50-year anniversary of Concorde’s maiden flight from Toulouse to New York City. It tells the story of the 27 years the legendary plane graced the skies, through the designs that shaped it.

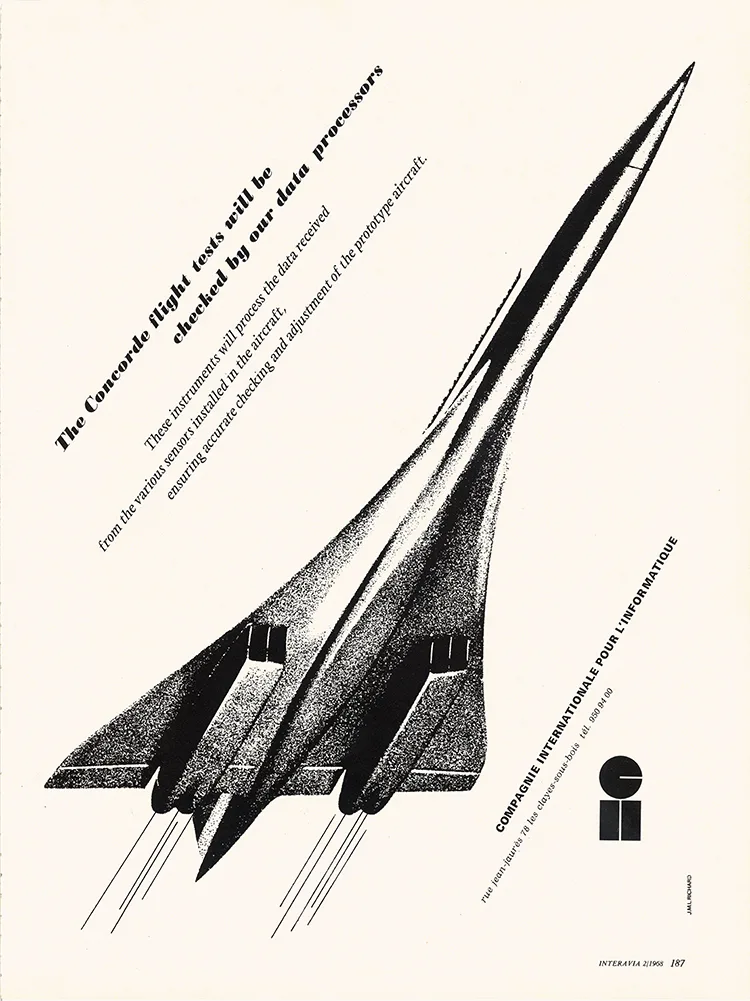

The Concorde itself was a coming together of French and British engineering during the 1960s; a collaboration that seemed to have surged right out of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

In the foreword to the book, Sir Terence Conran calls Concorde the most important piece of design created during his lifetime. In many ways, Conran means more than just the physical plane itself; he means the Concorde brand, and the idea of Concorde as understood in the popular imagination.

Conran, who designed the vessel’s seats and the interior of its British Airway’s waiting lounge in the 90s, speaks of the plane’s elegance, its optimism, and the way that it pushed the boundaries of what people thought was possible, as the very best designs often do.

“With Concorde, there’s this idea that design could change the way people lived, the way people traveled,” says Lawrence, describing the corporate utopianism that made it possible for people to arrive at a destination hours before they had even taken off. “It’s a kind of optimism you don’t see in design anymore, except maybe in Silicon Valley.”

The miracle of Concorde is that its revolutionary, iconic design is purely functional. The physics of the craft informs its shape.

Part space race and part vehicle of the stars, the Concorde represented future instantaneity as well as ritzy glamor. Photographs of famous models and musicians drinking champagne in the tiny cabin were just as important to the idea of the jet as its feats in engineering. So too were the menus by Christian Lacroix and Jean Boggio, dinnerware by Raymond Loewy (which Andy Warhol encouraged friends to steal — “it’s a collectable”) and futuristic napkin rings also by Conran.

All these carefully plotted details culminated in what Lawrence calls the “Concorde lifestyle”– that jetsetting sensibility that later found its home in aspirational magazines like Tyler Brûlé’s Monocle.

“It was a club in the sky, filled with important people,” says Lawrence, listing off regular British passengers like David Beckham, Joan Collins, Paul McCartney, Elton John, Annie Lennox, Sting, Mick Jagger, Elizabeth Taylor. “It’s like that feeling of being backstage in the secret, safe space of the green room, but instead of being behind a stage, you’re in the sky.”

Queen Elizabeth celebrated her 85th birthday aboard the supersonic jet, and in 1985, Phil Collins notoriously flew the Concorde so that he could play both the London and Philadelphia LiveAid concerts, amazing viewers watching the televised event at home.

While Concorde’s advertisements and on-board gifts promised a luxury to match the plane’s hefty ticket price (a round trip from New York to London in 1997 was $7,995), its powerful look was informed by its purpose.

“The miracle of Concorde is that its revolutionary, iconic design is purely functional,” writes Lawrence in Supersonic. “The physics of the craft informs its shape.” Its pointed nose and slender, dainty length visually imply movement, especially when seen next to the regular, cumbersome passenger planes on the tarmac, and its interior lacked any distracting decorative elements, with tiny windows and narrow walkways maximizing speed.

It was painted white to deflect the splintering heat as it cascaded through the sky like a comet. As its form matched its function so perfectly, Concorde’s distinctive silhouette quickly became a shape imbued with the idea of progress. It was a logo for tomorrow.

Lawrence’s book charts the aircraft’s branding history, and how both Air France and British Airways took different approaches for the advertising and passenger experience, on and off the plane. While France opted for its own historic modernism for branding, British Airways went for a pompous, regal sensibility that matched the sense of luxury.

Air France was the first to hire an outside designer to translate the technological innovation of the jet into a solid identity system, and the company turned to modernist Raymond Loewy for the job. His lollipop shaped spoon and whimsical knife and fork playfully nodded to the shape of the aircraft itself – its narrow size and iconic nose. The designer also furnished the airport lounge in Paris with Le Corbusier chairs to articulate sleek modernity.

Colored fabric seat covers aboard offset the small cabin area, making the interior feel bright and spacious. The all-important modernity was reinforced by Air France’s flashy logo – created by the French typographer Roger Excoffon – a series of swift dashes that look like a shape passing by in a blur.

It’s a kind of optimism you don’t see in design anymore, except maybe in Silicon Valley.

“Air France perfected the design, in my opinion,” says Lawrence, proudly showing me his Air France powder grey Concorde matchbook, which is elegantly brushed with its own splintered logo.

For passengers aboard the early British Airways Concorde, guests were served tea in royal bone china bowls – Lawrence managed to buy one off eBay – and decorative crowns adorned wine menus encrusted with golden ink.

In the 1980s though, to match Air France’s forward-thinking aesthetic, British Airways changed its brand into something altogether more sophisticated and contemporary.

After several additional adjustments over the decades, in 1998 the airline began working with Conran, who brought the interior of the jet and its waiting room up to the right speed. As if in conversation with Paris’ Charles de Gaulle Airport, he filled the Heathrow and JFK lounges with classic Eames chairs.

It was during its “peak obsession”– when Lawrence was outbidding other collectors for paperweights and wallets, pen-holders and champagne buckets at auctions – that the Concorde announced its last flight.

“It was a now or never moment,” recalls Lawrence. He’d recently started his own studio, and had amassed just enough British Airways flight points that he could afford a one-way ticket to London. “It sounds so unglamorous, doesn’t it? That I paid for my one and only Concorde ticket using my air points… But that’s how I did it.”

The trip itself was “kind of surreal, and kind of normal all at once.” The graphic design, the view of the earth, and the service all met Lawrence’s high expectations. He snuck a couple of coasters into his bag for his future book, as well as the safety instructions, which looked so peculiar with the Concorde silhouette on them.

Lawrence was surprised by how old, and actually quite retro, the interior felt. “Yes, it was amazing to be eating lunch flying at 1,350 miles per hour, but really, it’s amazing that we all fly domestic airlines at 500 miles per hour and think little more of it than hailing an Uber ride,” he says.

Maybe it became clear to Lawrence that somehow the Concorde is more fiction than fact, compiled in our imaginations from the advertisements, popular culture and humble ephemera that carried its silhouette. A vehicle that’s more paper and dream than space-age steel.

Flash forward to 2018 – a tiny selfie of Lawrence aboard the Concorde illustrates his author bio page in Supersonic. Even slightly blurred you can see his pre-take-off excitement – the book itself exists in that spectacular moment of anticipation. It doesn’t directly articulate what the Concorde necessarily was, but rather the idea of the plane, as pure, real-life fantasy.

Lawrence’s collection of functional and fantastic design represents a time that never quite came to be. It records all those particular elements that made people marvel every time Concorde made its elegant, unlikely path across the sky. There was the future.