When she begins one of her watercolor works, Chioma Ebinama does a plethora of research into her subject matter and makes sure she’s in a calm state before putting brush to paper. In turn, she hopes her pieces can be informative and meditative for those who come to view them. Here, she tells India Blue van Spall about how she’s preparing to take that ability to impact her viewers a step further as she starts work on her first children’s book.

Cover image courtesy of Fortnight Institute.

Chioma Ebinama never felt like life as a full-time artist was a viable option. “I’ve always been drawn to creativity, but was reluctant,” she says, basking in the sunlight of her Grecian apartment. “I’m a second-generation Nigerian-American, so I didn’t really grow up with this idea that it was even a potential path.” Since deciding to pursue it, the 32-year-old sociology graduate has spent the last five years exploring the recurring themes of matriarchal power, race and pre-colonial philosophies via a series of soothing, poetic and impactful illustrations, sculptures and wearable art.

In the last three years, she’s carved her own slow-paced path: taking residencies across Mexico, Lagos and Brooklyn, collaborating on selected group exhibits across the globe and even hosting workshops on her meditative drawing practice around North America. “I see all of my experiences in different countries as little experiments,” she says. “I want to learn more about how to be a person of the world, and whenever I’m gripped by fear or doubt, I remind myself that there are many ways to live a life.”

In a whirlwind of spontaneity, the Maryland-born creative recently upped sticks from the hustle and bustle of New York to live in Athens. What was meant to be a one-month trip became something a lot more permanent, and it’s opened the artist’s eyes to Greece’s rich cultural history. “Pre-colonially, Greece had such an interesting position in the Western world,” she says. “Being based in New York for 10 years and focusing more on this dialog of Blackness in America, I always wanted to avoid taking in any information I thought was Eurocentric. But now I’m thinking about how much that history is connected to my history as an African and how I’d like to be more informed.”

I want to learn more about how to be a person of the world.

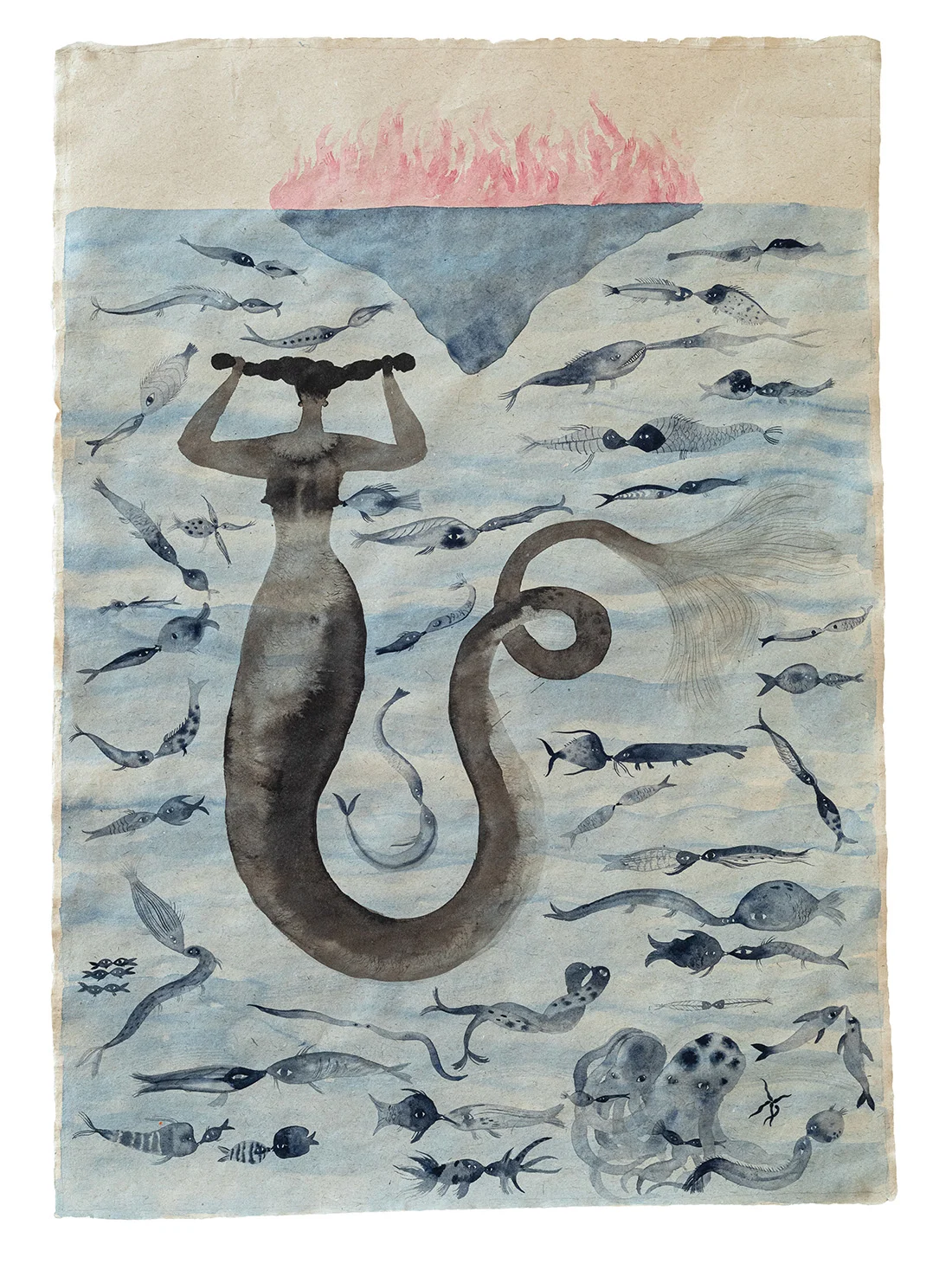

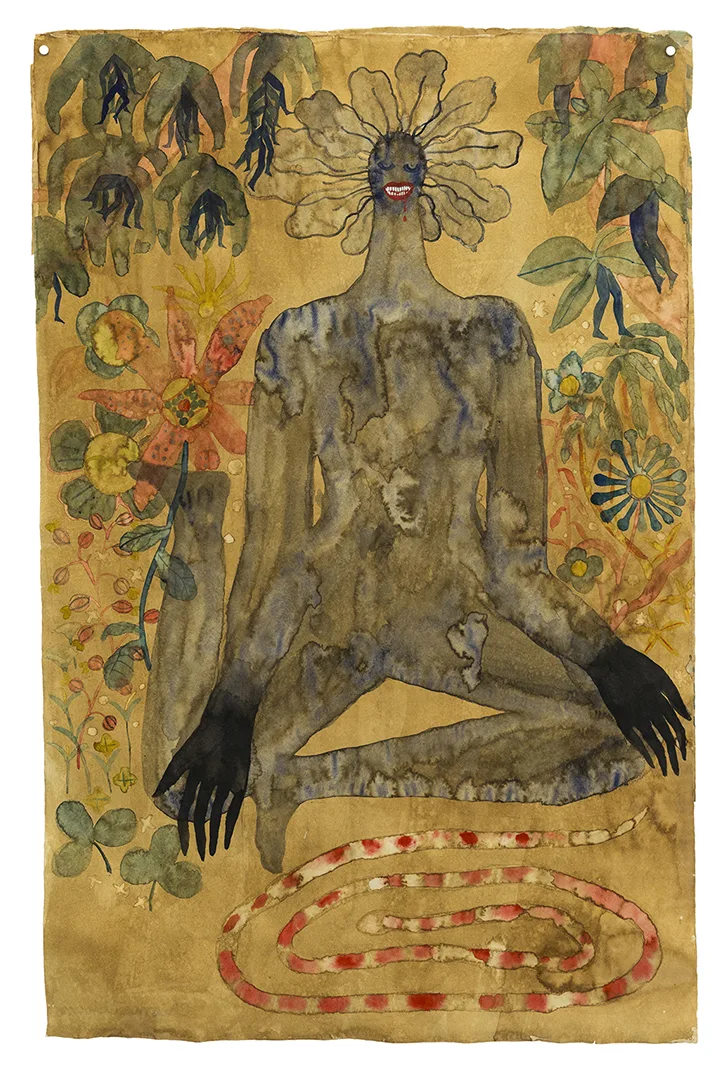

Chioma is making the most of being in an exhilarating city. She’s fascinated by prehistoric sculpture, new myths and understanding “how our ideas of being in the world have come to where they are now.” “I’m primarily interested in prehistoric and pre-colonial imagery,” she says. “The sort of work that we consider outside of the major canon of art history.”

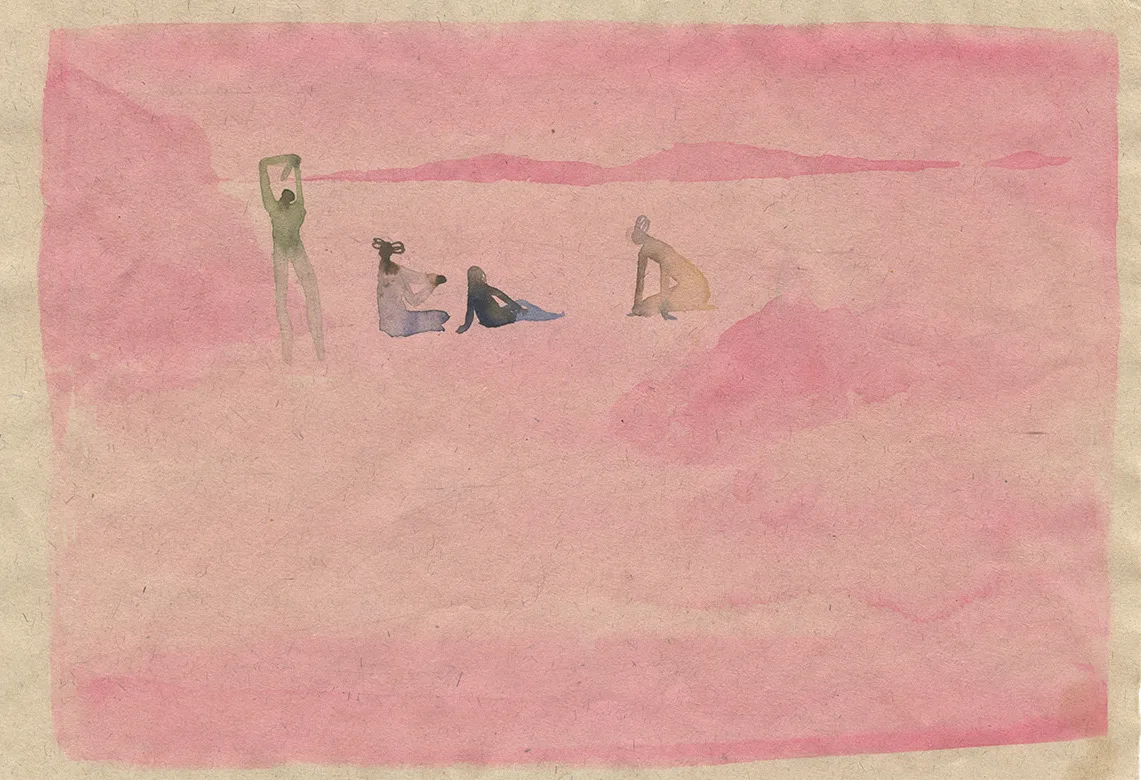

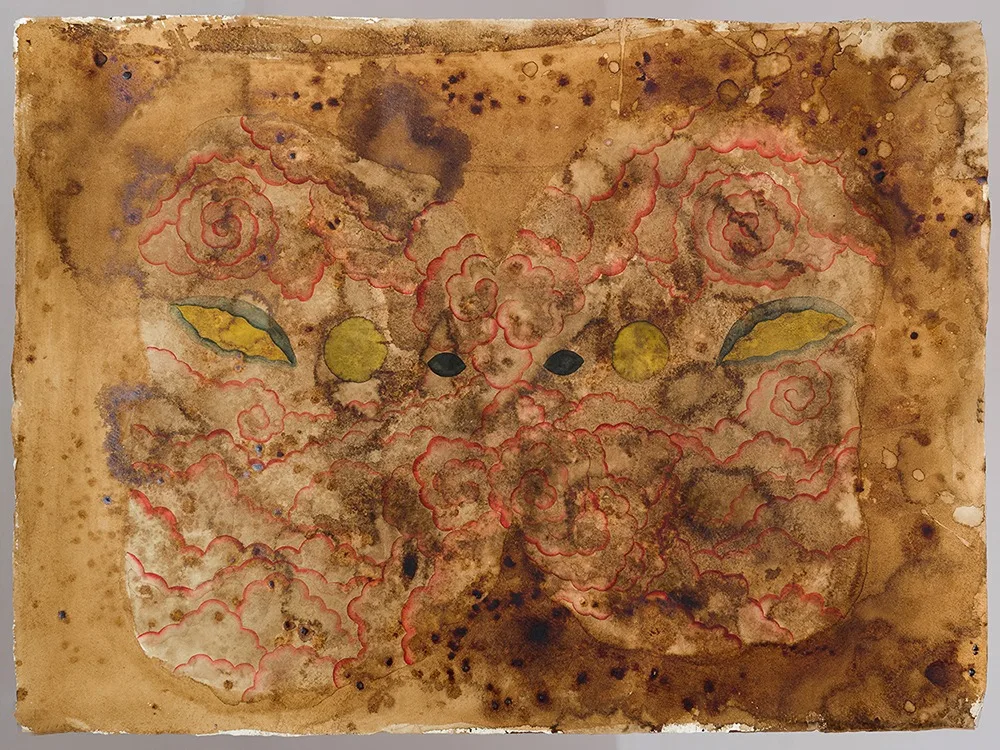

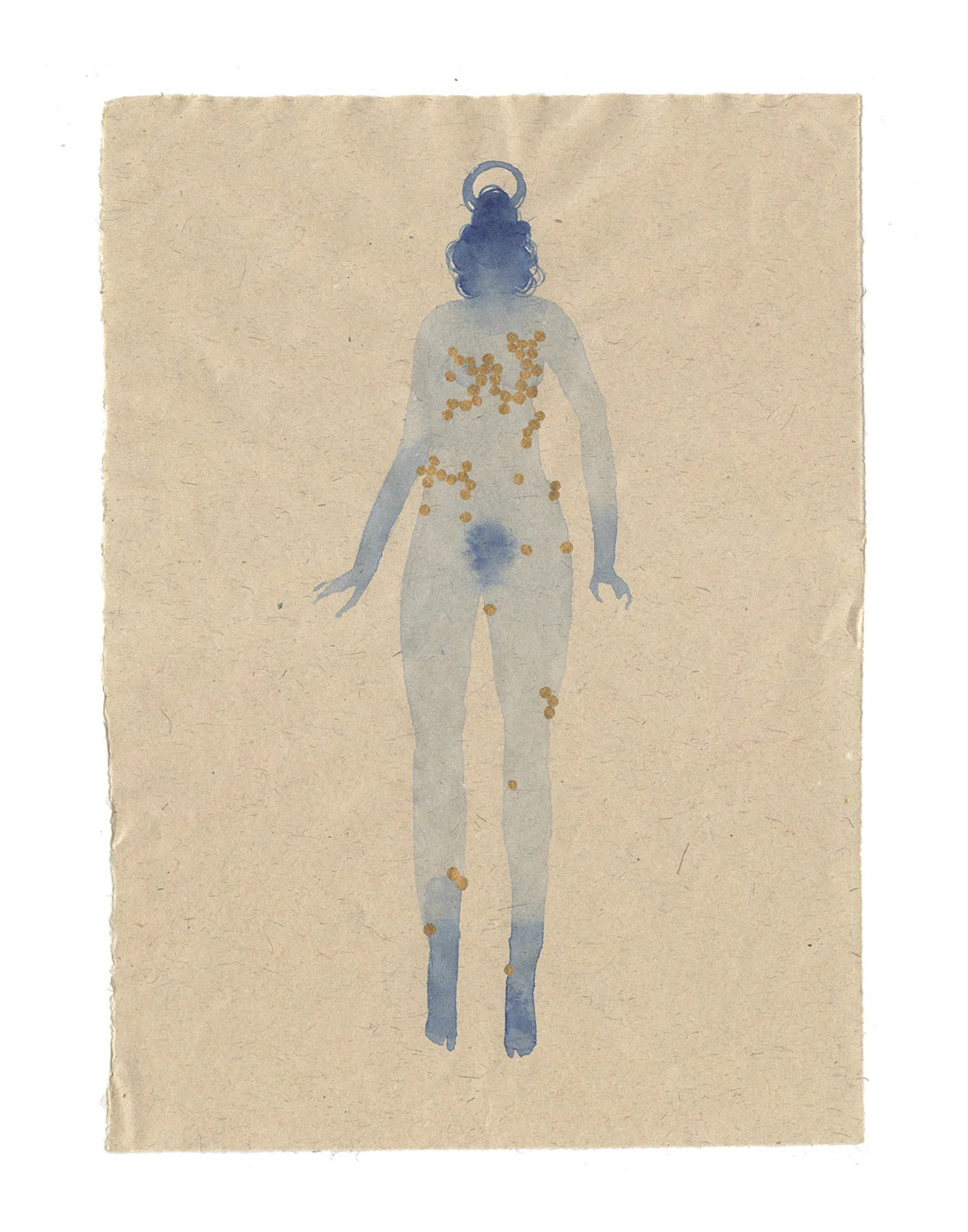

Whatever the subject matter, Chioma always communicates it in soothing watercolor brushstrokes, and scrolling through her work can be meditative in its own right. It’s no surprise, then, that Chioma feels the need to put herself in that same relaxed state before she puts the brush to paper. She steps away from traditional methods to get herself in the creative zone, often turning to her journal and the “cosmic” genre of disco. “I definitely live in a wall of music, and I like to be in a groove and dancing,” she says. “It presents a way to stay in a calming state. Then I can start reading, notetaking and accumulating images in my mind. It feels more like cooking, where I’m putting little bits together to make something that almost feels like a visual poem.”

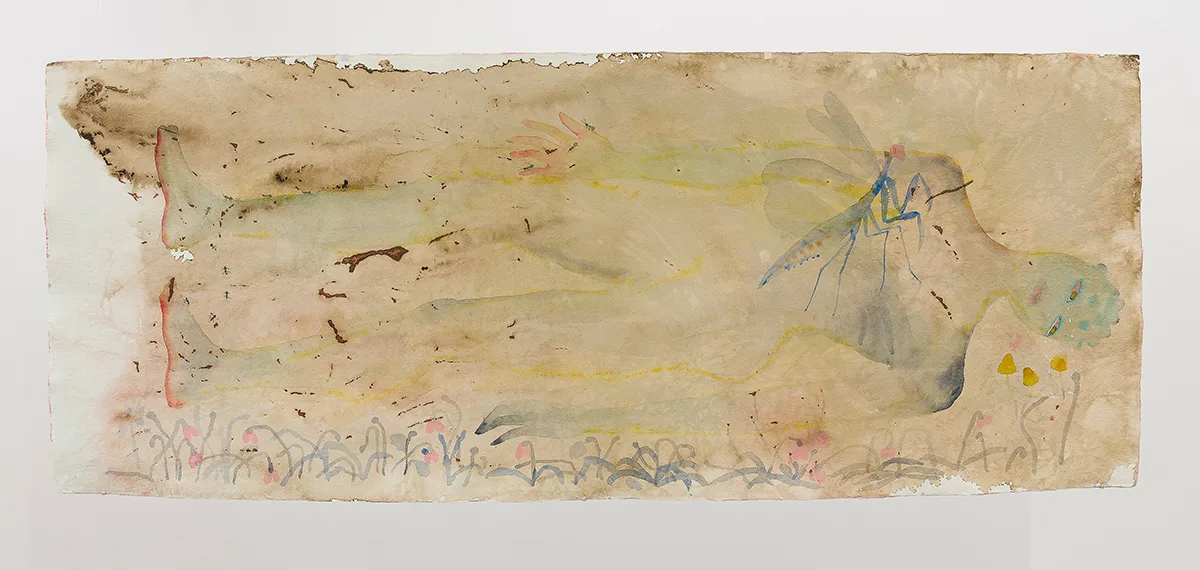

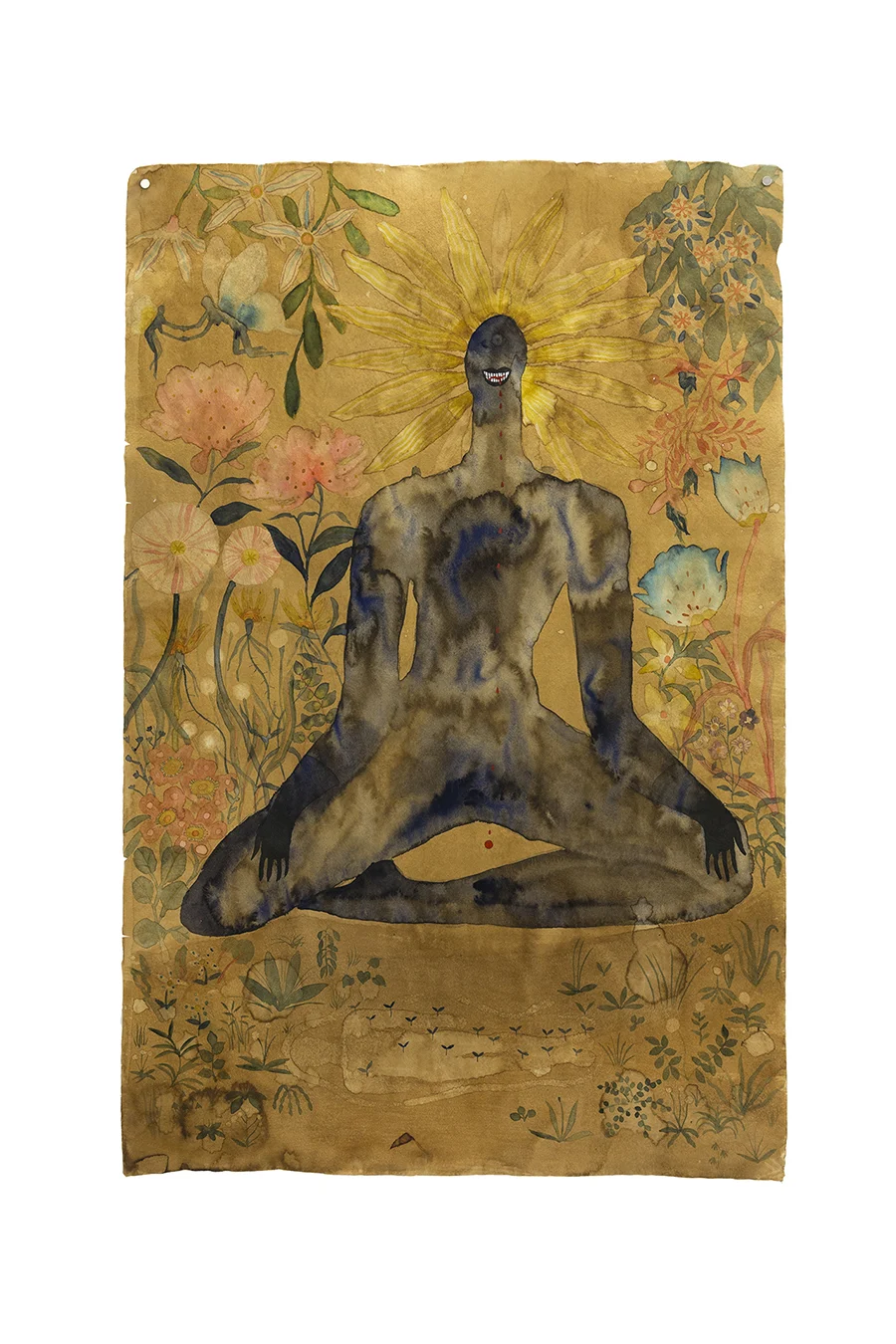

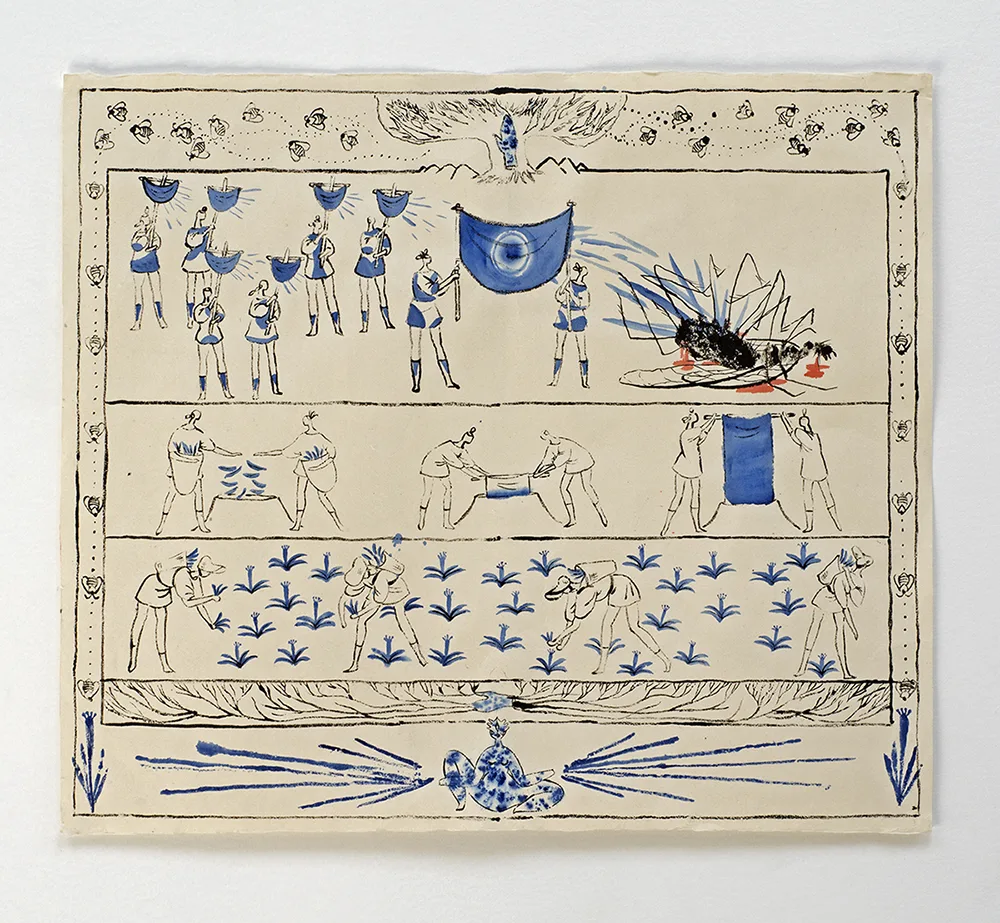

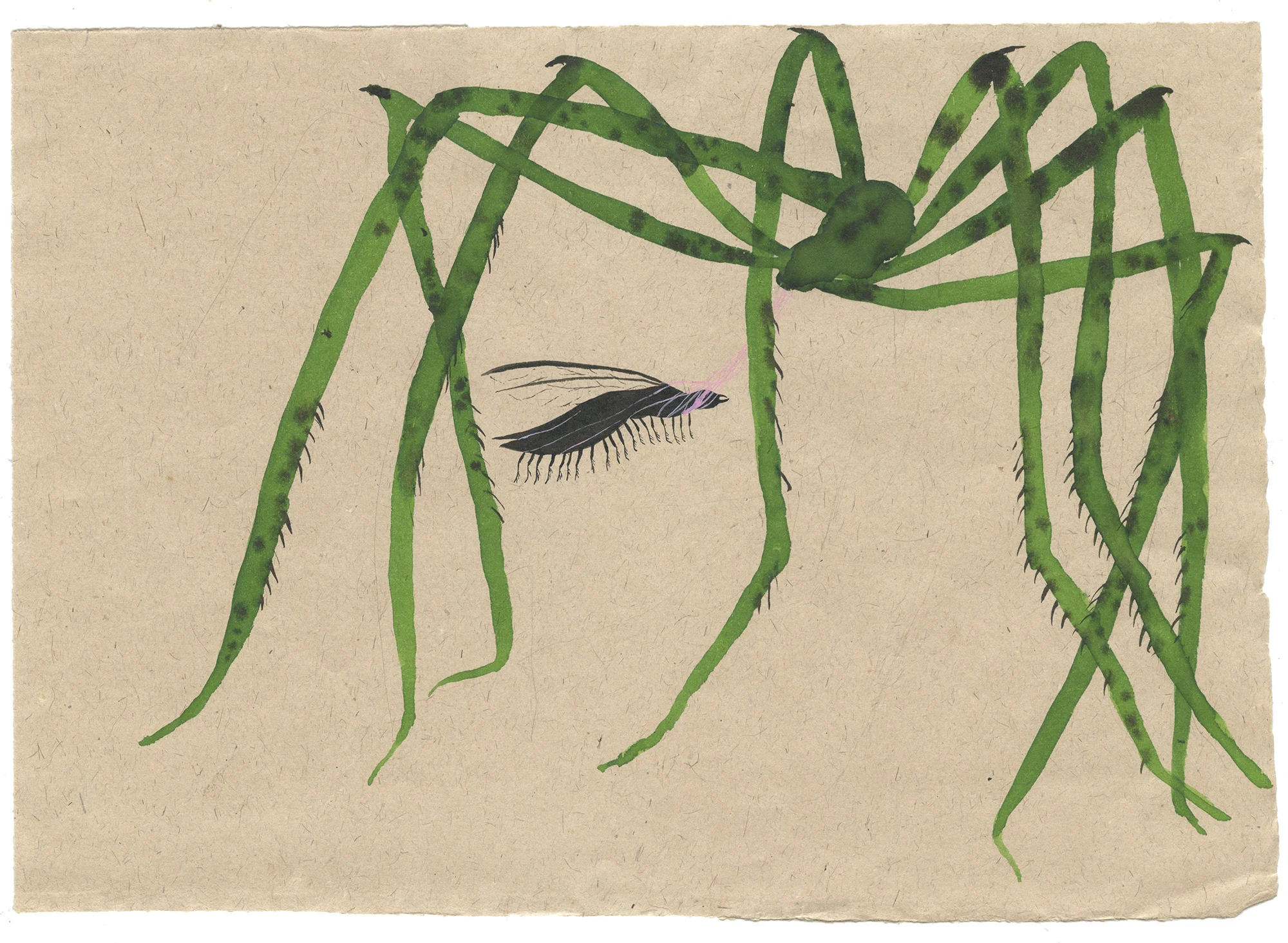

As demonstrated in the mixed-media artist’s first collection, titled Ritual for a New Direction (2016) and curated by Raphael Guilbert, Chioma has always been drawn to the mythical world. Through a series of intricately-drawn ink monoprints and sculptures, she explores how a history of images can create a sense of cultural identity, conjuring eerie demigods and demons through watercolor and taking influence from both pre-Columbian Americas and West African mythology, as well as American folk art and Japanese manga.

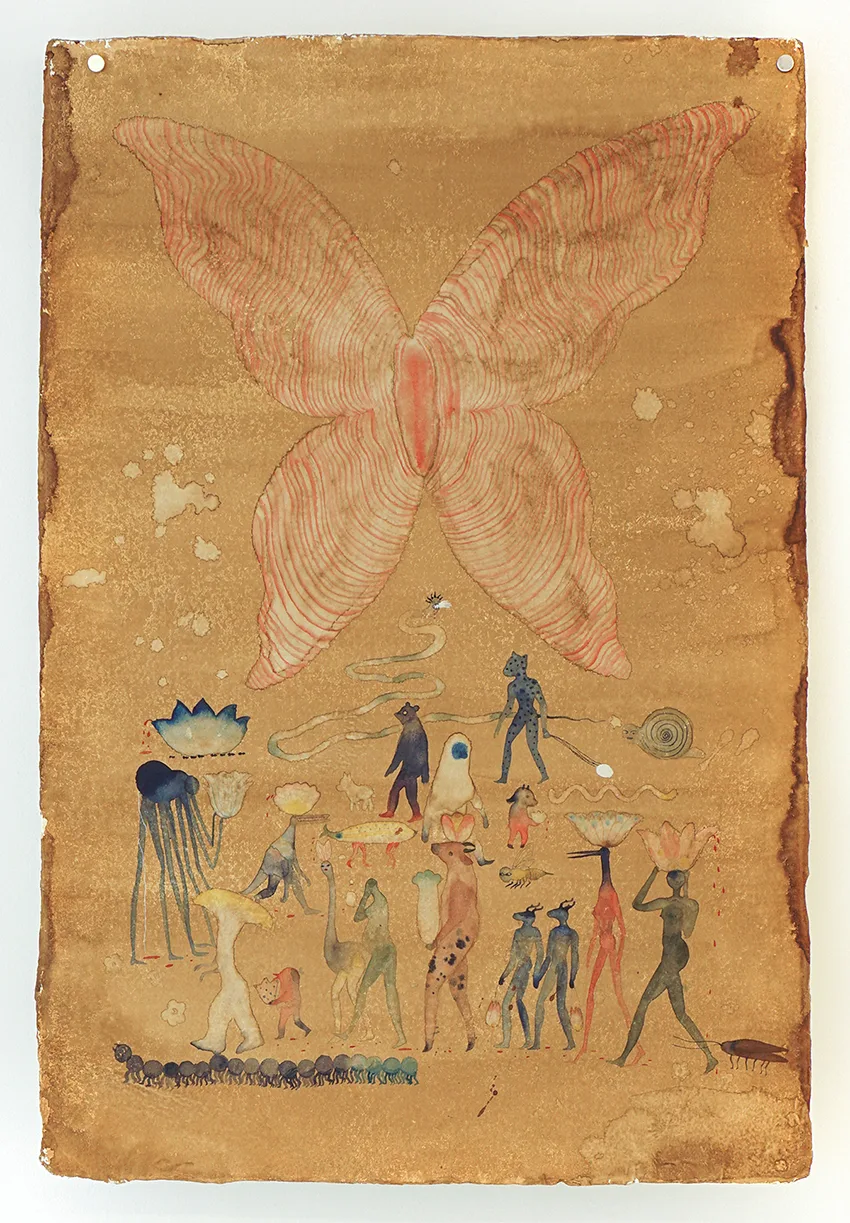

Her most recent exhibition, mud & butterflies, presented this year at Catinca Tabacaru Gallery in Bucharest, as well as Leave the Thorns and Take the Rose, a solo showcase at The Breeder Gallery in Greece last year, focus primarily on feeling, documenting the artist’s emotions and mantras through 2020 and 2021 as the world came to a standstill. This reflection on feelings and mantras is an overarching approach to her work, and rang true for her exhibition immediately before the pandemic, Now I only believe in... love at Fortnight Institute in New York, and her solo exhibitions coming up this October and November at Maureen Paley in London and Salon 94 in New York. “I want to make work that is still accessible,” she says. “What I produce is definitely smart, but I'm really turned off by a lot of the academic language in contemporary art and the inaccessibility of white cube culture.”

I’ve just been thinking about the need for joy, and submitting to a more childlike impulse.

With every show she makes a new body of work, “partly because I get bored very easily but also the work is always influenced by whatever is going on in my life,” she continues. Though her subject matter fluctuates, Chioma’s mission is clear: to educate and entice using her practice as a form of social commentary. As her approach continues to evolve, the signature cool blue hues and bold inks from previous collections have been switched in favor of playful brushstrokes, vivid colors and more abstraction. “I’ve just been thinking about the need for joy,” she says. “Joy in work and play, just submitting to a more childlike impulse.”

In that vein, Chioma’s trying her illustrative hand at a children’s book. “It’s a very different process to my fine art, which I feel is very fluid,” she says. Learning, comparatively, to stick to stringent deadlines and enjoying the challenge of building on a narrative, she’s bringing to life a manuscript by Kevin Young, the former director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York. Titled Emile and the Field and giving a voice to people from more marginalized communities, the picture book depicts the life of a young Black boy meditating in nature.

“It gave me a lot of freedom visually. I’m excited to be putting something out that’s for kids, but especially for Black kids,” she says. Just as Chioma said there are many ways to live a life, she’s realizing that there are many ways to be an artist, whether that’s the different mediums she can use or the impact her work can have on those who come across it. “The book really changed my perspective on what I want to express. I hope that my career can present a different idea for how being an artist can be.”