To celebrate our partnership with A Vibe Called Tech—a new creative agency established to explore the intersection of Black creativity, culture and innovation— we are collaborating with independent magazine Plantain Papers to celebrate the importance of Black folklore. Through conversations with seven storytellers, Plantain Papers’ founders Lemara Lindsay-Prince, Tamika Abaka-Wood, and Tahirah Edwards-Byfield explore how Black folklore is an omnipresent connector to identity and morality.

This feature is part of WePresent's partnership with A Vibe Called Tech.

Weaving together the threads of connection across the global Black diaspora is why Plantain Papers exists. “People with a side of plantain” is our mission. Because yes, plantains are delicious, but more importantly, they serve as our inside nod; a device to say “we see you, we know you, we are you” to the communities who grew up with the fruit as part of their palette.

Finding connection and fostering community across the most commonly accessed parts of Black identity is where most of our work and lives exist and intersect. Yet there’s something mysterious about the intangibility of a collective consciousness—about the things that present themselves as tangible, as a way of being, knowing, and doing intrinsically set in our bones. That’s what made us want to explore folklore.

We’d hazard a guess that just like us three, most Black folk aren’t actively thinking about African folklore on a regular basis. We have to reach inward and find them amongst our memories. But the stories are almost always there. Even if incomplete, even if just a fragment of a thread that feels so familiar and nostalgic, it instantly takes us home.

Black folklore isn’t given the reverence of European stories. Western imagination doesn’t allow for Black people to exist in the whimsy of fairy tales without friction. Black supernatural phenomena like Voodoo, Obeah, and Juju are treated as more sinister than their European counterparts. Folklore characters like Ti Malice and Bouki aren’t said in the same breath as Hansen and Gretel, and Anansi (or Kwaku Ananse, or Anasi as he’ll be called throughout this feature) is not mentioned with Goldilocks.

Yet Black folklore perseveres.

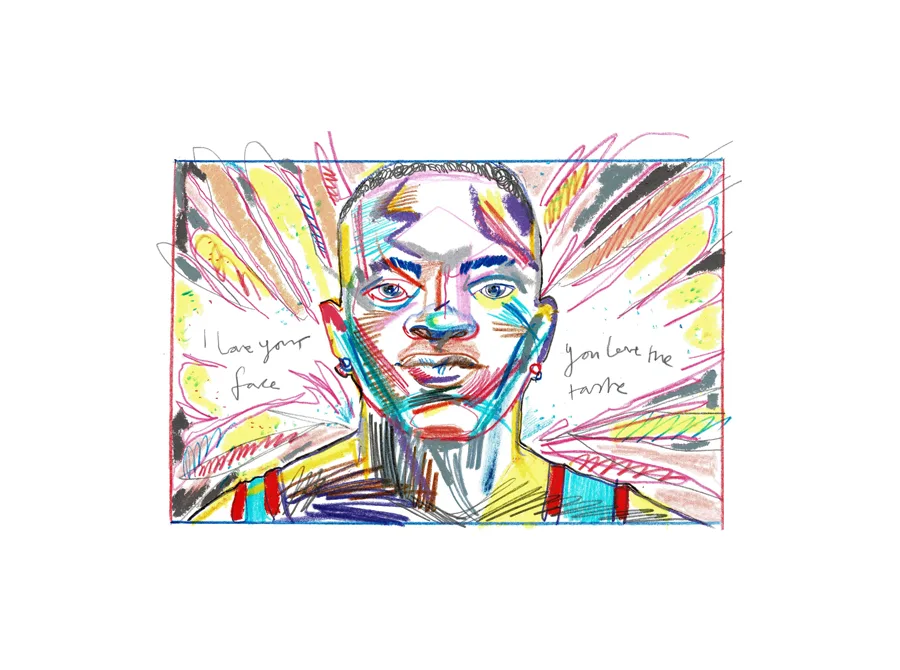

African folklore is the foreparent of Black storytelling through literature, poem, song, and movement. It’s what set the foundation for the reclamation of our stories and owning of our narratives.

African folklore is the foreparent of Black storytelling through literature, poem, song, and movement. It’s what set the foundation for the reclamation of our stories and owning of our narratives.

And oral storytelling is still a central and cherished part of Black communities around the globe. Whether tales are shared around the dinner table, or lore is turned into spectacles with performances. These stories always show up somewhere, in our own personal journey and our collective ones.

Propelled to hear them, to preserve them, and see if we could weave a thread of connection, we turned to seven Black storytellers ranging from ages six to 70, in Bermuda, Brooklyn, Accra, and Toronto, to see if we could understand a little bit more about the way Black folklore has shaped their individual concept of identity and morality.

Kuukua Eshun

Kuukua Eshun splits her time between Ghana and the USA. She wholeheartedly believes everyone can tell a story but “there are some people who have a unique assignment when it comes to storytelling”. Kuukua is a proud African woman. She is an award-winning film director and creative, and a force to be reckoned with. For her last birthday, she generously gifted the world with a short film which she narrates in her native tongue of Akuapem. Akuapem is the language in which Kuukua is most mesmerizing. It is the language she is most at home within. She narrates from a palpable place of intimacy, security, and warmth.

“This process has already been very nostalgic because I have started to reflect and analyze and think about the deeper meaning of what folklore means to Africans,” says Kuukua. “The actual meaning behind Kwaku Ananse the Spider. He’s smart, he’s cunning, he’s kind and he’s slightly problematic. That’s me. That’s everybody. That’s human nature and will be forever. I was having a conversation with a friend and she made a point that even the drawing of Kwaku Ananse is very similar to the infinity sign.”

When we talk about folklore, we’re also talking about the concept of time. Western society thinks of time as siloed—there was the past, there is the present, and there will be the future. But Ghanaians stand in the presence of Sankofa. Visually and symbolically, “Sankofa” is expressed as a bird that flies forward while looking backward with an egg in its mouth. Proverbially, it means “it is not wrong to go back for that which you have forgotten and learn from the past to move forwards”. Kuukua is one of many Ghanaians who have been raised to experience and express the concept of time as nonlinear—constantly passing, renewing, and refreshing, just like the infinity symbol, just like Sankofa.

When retelling the stories of her childhood, Kuukua refers to the trickster spider as “Kwaku Ananse the Spider” in an intensely personal manner. There’s a subtle intimacy hidden in the language she uses too. Kwaku is a given-name for male children born on Wednesday. In Ghana, these names are said to give an indication of the character of those born on specific days. There are cultural traditions and ways of looking at the world that are in the marrow of Kuukua’s bones.

“I remember for so long, growing up in the USA, something just felt so empty and off. In Ghana, the skies are more blue, the grass is more green, everything is just so refreshing and beautiful,” she says. “I really appreciate the little details, those details that infuse life, and that comes through in the ways I tell stories.”

Kuukua’s family is made up of a mixture of tribes. She is Ga from Labadi, Akuapem from the Eastern Region, and also Fante from the central part of Ghana. Her great-grandparents migrated from Congo to Ghana. Movement of people across imaginary borders has happened since the dawn of time. Kuukua tells us the traditional fable of when Kwaku Ananse collected all the wisdom of the world in a wooden pot. She seamlessly makes the connection between Ananse’s travels across the globe and the return to his home, with her own journey from Ghana to the USA. She is Ananse, and Ananse is her.

When we talk about folklore, we’re also talking about the concept of time.

The fallibility of individual memory becomes evident as we start to venture back to when she first heard this particular Kwaku Ananse the Spider tale:

“So I’m in the living room, in an old house in Awoshie. The story is being told by one of my Aunties and it’s so fresh because she tells me the story in my local language, which is Akuapem. I think about 10 people, including an uncle, my teachers, and Aunts have told me the same story in various ways. There are different memories being infused together, it’s beautiful.”

However, we begin to explore the robust magic of collective, shared memory whilst being vastly aware that we’re carrying different bodies, different sets of experiences and perspectives. Plantain Papers remember when Kwaku Ananse the Spider stories were told. The elder began by calling out “Once upon a time” and it was the audience’s duty to rhythmically respond “Time-Time”. There was no binary distinction between storyteller and audience—the experience relied on a symbiotic relationship.

“Wow, I actually forgot about that. You just took me back. Like, what, 15 years,” says Kuukua “I think for me, one of the biggest things we share is our identity as people of the African diaspora. The fact that something you said triggered a memory that I had is special. We didn’t grow up in the same house or in the same family. But the fact that we can share experiences through storytelling is so beautiful. Stories are made to travel far and wide.

“Whether you grew up in Jamaica, or Nigeria, or Tanzania, or Uganda, or Zimbabwe, it does not matter—the basis of Kwaku Ananse the Spider stories remains timeless. And that’s what keeps us connected, because the principles of life remain the same.”

Alex Brueggeman

The connection that Kuukua speaks of is what brought 32-year-old Alex Brueggeman to Haitian folklore. That connection to something greater than our personal cultural experience happens on an almost cellular level before we can even put language to it.

Folklore called Alex in before he even understood the seminal role it would play in not only understanding his identity but defining it on his own terms.

“At first folklore was the only kind of tether that I had to my Haitian identity,” Alex explains one balmy afternoon via Zoom from his apartment in Brooklyn. “My biological father is Haitian, my biological mother from Curaçao, and then I was adopted by a white German-American family; hence my last name. I have a Korean sister. That’s like a recipe for an identity crisis, you know?”

An oft-undiscussed experience of many transracial adoptees is one of trauma from feeling disconnected from their birth culture. “I think because I didn’t have ready access to my heritage—my Haitian heritage, or my Curaçaoan heritage—I spent a lot of my life just kind of searching for it. Like, what does Blackness mean to me? And I think I spend a lot of my time trying to define myself in terms of other people’s definition of my Blackness.”

Alex is the type of person who does everything with intention. You feel it in how he takes a contemplative moment before speaking, and the way his warm smile creeps across his face as he completes a thought. That intentionality is present in how he sought out connection with his biological family’s culture before even meeting them as a teenager, studying French upon learning of his father’s Haitian roots, and seeking out Haitian and Caribbean literature and stories to begin to plant seeds of connection.

“I became an anthropologist,” he explains. “A lot of what I studied was the oral histories and folklore, but it was always other people’s stories and written accounts. It wasn’t until I reconnected with my Haitian family that one of those stories actually became my own.”

Alex’s tale of experiencing the story that rooted him into his Haitian identity reads like lore itself. Aged 20, he traveled to Haiti for a family reunion. Relatives from Canada, France, the US, and other places in the Caribbean all converged for a huge homecoming in an affluent area outside of Port-au-Prince, where his grandmother lived. And at first, it felt...awkward. Here he explains his experience of that reunion:

“I went to this family reunion still feeling not like I really belonged. I understood, and I saw the people who looked like me, but I didn’t feel at home there. I didn’t have that same kind of history. And I was also very much raised in the tradition of American Blackness too. You know, even though I was adopted by a white family, I was surrounded by Black Americans. And that was the kind of culture I’m most identified with; I was very, very American. So it was a culture shock. And it was also kind of like a déjà vu. Almost like I could see the residue of myself in this place, and in these people. But as far as a full picture, I couldn’t really see myself within it.

“My family, they’re light-skinned Haitians. They have a very storied history within the country, and a lot of that history is not really good. A lot of it is them exerting the privileges that their lighter skin afforded them on a lot of other people. My grandmother had a helper named Martine. If you have any kind of money in Haiti or most places in the Caribbean, you have people to do the cooking, the cleaning, the driving, the gardening, everything. She’d been with the family for over 20 years and she was dark-skinned. She stood out against this sea of light, bright, high-yellow assholes. And she never said much, you know, it was definitely a ‘don’t be seen or heard’ situation. She was never mistreated, but she was always reminded of her place in very subtle ways.

“I remember in the midst of this day party, I walked into the kitchen and I saw Martine with the young kids. This was the first time that I’ve really seen her animated, she came to life with these kids. She told them a story while she was making the dinner, so she was chopping onions and peppers. And then she said, ‘KRIK’, and then all the kids said KRAK’.

“‘KRIK, KRAK’ is a call and response—‘KRIK’ means you have a story to tell. And then if the audience wants to hear it, they say KRAK’.

“So I was listening to the story. And I felt like a kid, you know? This was my first time hearing that story and my first time kind of feeling like I was a part of it. And it really made me understand the legacy of these kinds of stories, and the legacy of the culture and that kind of residue that exists even if it’s far at times. It became something that I never ever really forgot.

“It was kind of just like, ‘Okay, so now I’m Haitian, I get it now.’

“I think in the tradition of Bouki and Ti Malice, it’s not so much the story but the characters themselves. There’s so many different stories, and in all of them, I think Bouki represents the people who are oppressed, the people who are kind of manipulated, who are downtrodden, the people who don’t have education or great resources. And then Ti Malice is the cunning trickster, the person was always fucking Bouki over. He represents the elite. I think there’s a lot of sociopolitical undertones to it. And with that story, while it’s told to the kids and it’s really, really funny, you know that there’s something deeper to it.

“And I always thought it was so interesting that the person who was telling that story was Martine—the helper—and not my grandma. And I think that says a lot too. I think the teller of the story is the main character.”

Ivo Vita Genesis Bell and Chrystal Genesis

British-born Chrystal Genesis ruminates on how she came to know folklore and the importance of passing this on to her children:

“I think the first time I heard Anansi must have been my mum reading to me, because it almost feels like a story that I’ve known from the day I was born. I also grew up in a very kind of Caribbean, but also African, Black area. So everyone kind of knew about it. It was just always something that we always knew about.

“I think growing up and getting older you connect and understand more about your culture. And the fact that this was a story that came from Africa and reached the Caribbean is extraordinary. And oral histories and folktales are so important and crucial.

“My children are mixed race. So for me, it’s very important for them to understand where they come from, and for my culture to be a central part of that, because we do live in a Western society. We live in America, and we’re from the UK. So for me, it’s vital that my children know these stories, and actually, they’re so proud of it and they love them. It was just a no-brainer, really.”

On a typically humid August evening, Ivo and Vita took the A train with their mum Chrystal from Harlem to Brooklyn to take pictures for this piece. The energy of New York City was particularly frenetic. This was the week in which the tail-end of Hurricane Ida and flash floods were lingering in the air but not quite making their potential for destruction known. We turned the AC off, as one must do with audio recordings (!), and gathered in the basement of the Brownstone to tell some stories. The elements, theoretically, were not working in our favor, but they served as a reminder of the types of futures our young people will inherit from us.

Young people are people. They are a distinct subset of people who have an astute and instinctive way of getting to the heart of matters incredibly quickly. When speaking with Ivo and VV about where they thought the origin of the Anansi stories came from, Ivo, without missing a beat, responded: “It was my parents. That night, I first remember hearing it, it was my parents and my grandma that told me. My grandma taught my mom, and then my grandma’s mom taught my grandma, and it kept going on and on and on like that from my ancestors.”

Beyond the understanding of how the stories landed in his world. Ivo then linked his experience of Anansi to even wider cultural impact: “The Anansi stories come from Ghana actually, some of my ancestors told them and told them and told them, because it was from Africa, and then it got really big in Jamaica, so my family knew about it. And it traveled all the way to me and my little sister.”

I think the first time I heard Anansi must have been my mum reading to me, because it almost feels like a story that I’ve known from the day I was born.

This is where Vita, six years old, comes alive and is compelled to share her perspective: “So the book started in Africa. Then they moved on to Jamaica, and then it moved on to lots of different countries. I wouldn’t be scared of Anansi. If I knew that he was Anansi, I wouldn’t be scared. But if he was an actual tarantula, I would just run for my life! Anansi is a colorful spider. But yeah, he’s Black too.”

Ivo naturally and confidently assumes the role of storyteller. These folklore stories are often told by elders, but he was turning 10 years old the next day and took the right of passage to double digits with excitement and grace. Ivo chose to tell us all the story of how the moon came to be.

It went a little like this: Anansi had six sons, and each of his sons had a special talent. One day Anansi’s life was in constant danger. Each of his sons contributed to saving their father’s life in their own way. The Sky God (Nyame) gave Anansi a light orb with the instruction to reward the one son who saved his life. They quarreled. They fought. They argued. Anansi could come to no conclusion, so instead the Sky God placed the light orb in the sky.

“Gods—they’re just, I don’t know, a whole different level of nice and kind and smart, you know? I mean there’s a lot of things that we can’t even give even if we tried. That not even one person in the world can give. But the Gods can.”

Ivo reminded us of the subtle ways in which folklore stories can decolonize our understanding of the world we live in. Ivo made no reference to a singular God in our conversation, unaware he’s sidestepping the Christian notion of God as an idealized prototype. But of course, at that moment, in that balmy August evening, we’re doing something far more tangible—we’re listening to nine-year-old Ivo tell us the story of how the moon came to be.

“Am I storyteller? Maybe it might be possible. Yeah. I read the story and also watched the story on YouTube. I have a lot of books in my bedroom. I have like hundreds, 200 maybe, so it’s really hard to find them. And it’s easy for me to watch the stories on YouTube. The development of technology is going on very high—it’s developing very fast so that Anansi can reach more people.”

Ivor Picou

Ivor Picou’s presence is grounding. The stirring, quiet confidence of a soul who intrinsically knows his purpose on Earth. Part of that purpose is unquestionably to be a storyteller.

Storytelling has woven itself through his own personal narrative; now 70 years old, Ivor migrated to Toronto from Trinidad and Tobago over 40 years ago. But not before discovering his voice in Derek Walcott’s words on the Trinidad Theatre Workshop stage. Once in Canada, his gift as a teller manifested through roles as an orator, dancer, actor, and teacher. He is currently working on a documentary on the origins of Steel Pan as a site of cultural and generational storytelling.

During our time together, he shares the story of Soucouyant—pronounced “Soo-koo-yah”—a shape-shifting, soul-sucking demon who appears as an old woman by day. Like much Caribbean folklore, the legend of Soucouyant stretches wide and far across the islands. Sometimes named Lougarou or Ole Higue, sometimes simply “Hag”, Soucouyant has found her way into villages in Barbados, the Bahamas, Suriname, Guadalupe, Guyana, and Jamaica, to Haiti and beyond. Ivor brings her to us from a small village in Eastern Trinidad called San Souci.

Personal resonance is an essential part of Black oral storytelling. It’s part of the magic that turns a story from all of ours—a gift of the global Black diaspora—to intimately mine and yours. That ability to see our environment, our circumstance, and ourselves is the reason these stories hit so directly.

In Ivor’s case, it’s the reason this tale excited and terrified him as his grandma (the first storyteller he heard tell it) told it as a cautionary tale for being careful going out unsupervised at night.

“All over the Caribbean, in places like San Souci, you know how dark it is at night? And it’s a racket sometimes going on outside at night, you hear all these creatures. You know, you’re hearing things chirping, right? You hear bats fly. And you hear animals grabbing other animals. And it’s like, ‘I ain’t going out there!’” he says. “I mean, I think I could have handled the creatures of the night. But the Soucouyant was just the top level, you know? At 10 years old, I just knew I was gonna die if I saw a Soucouyant...So the parents would tell these tales because the idea was, you don’t want your child wandering around yet, for whatever reason.”

Ivor muses over the bigger role—beyond entertainment value and morality—that folklore plays in the consciousness of collective Black identity. “When I was younger, the stories were just simply fascinating. Sometimes, you’d listen to a story, and you don’t want to move because you think if you move, one of several things could happen. You’ll lose the point of the story. Or, the ghost or spirit in the story might actually be back there! But the storyteller was just simply riveting. And that was the great part about it. So I was captivated by that. Later on, I began to understand the need for these stories. Because at the time, many of our stories weren’t written.”

As a student of global stories, Ivor understands how imperialism and ideologies around Western superiority play into how Black folklore is perceived. “They didn’t have [social] standing. At school in Trinidad, we were studying all these other people’s stories and folklore, and imagery. Our own stories were considered a few levels below ‘formal’ areas of literary study.”

“Formal” is often a thinly veiled code for white stories, literature, and art forms. Stories that had the privilege of formalized documentation, not disrupted by the fraught conditions of colonialization. Stories that were free to be passed down in text as well as through oral historians.

“Our stories don’t have to be ‘formal’. But there can be an acceptance of them, and a celebration of them because they made us feel that our experience was real. These are valid ways of living. Our spicy food. Our language. I love the language that we speak. Sometimes I just want to hear all these words and syllables that we had to twist out of shape to make it feel for us, you know? And here in Toronto, it’s even more important to maintain a sense of who we are, and what we want to be in this society. Otherwise, [Western] society can wrap you up and pigeonhole you into something that just deforms your understanding of yourself. So, it’s even more important that those stories that come out of our experience are told and celebrated.”

But Ivor theorizes the role of folklore in our communal consciousness goes even further than anchoring us in collective self-esteem. “[Folklore] gave people a way to try to explain stuff that, at the time, they couldn’t explain. I’m sure that’s what some of that was. For example, you have people who get sick, and have illnesses they couldn’t figure out because they didn’t have access to the best healthcare that was available in society. So they might want to know, ‘Why is this person’s hands shriveled up? Why do they have what they call a sore foot? That’s a big sore on your foot that can’t heal? Why does your foot swell up huge, huge, and won’t go down?’”

Historically, perhaps these stories provided a way to contextualize things seemingly beyond the ordinary human experience. Of course, technology, science, and our understanding of the world have evolved since these stories first began traveling across continents and generations. But in Ivor’s estimation, that doesn’t make folklore any less sophisticated.

Because our intrigue with the esoteric and supernatural hasn’t gone anywhere. Neither have unexplained phenomena. Ivor believes part of keeping the legacy of these stories alive is contextualizing them through our present-day understanding of the world—just like many of Hollywood’s biggest fantasy franchises, from Harry Potter to Marvel and beyond, already do.

With a wry smile and the glint of imagination in his eye, Ivor implored we wouldn’t even have to look very far to imagine the next topic for Black storytellers to turn into folklore: “We’re all experiencing this COVID thing. We still don’t know how it’s going to end. But even with all the scientific tools, here you have some micro-organism that says, ‘I’ll stay a step ahead of you.’

“So you can imagine some little character saying, ‘Let’s play games with the scientists. Let’s fool around with them. And just as they think they’ve got it together and they’ll catch me, I’ll shape-shift into another variant.’”

Yesha Townsend

Yesha Townsend(pronounced Ay-sha) is illuminated by a wash of light as she speaks. The intensity of the Bermudian sun boring down on her makes the flight of songbirds crossing its path cast a quick shadow over her face and on the white wall she sits in front of. Taking the call here, “a piece of limestone in the middle of nothing, in an endless sea”, has extra significance, as to speak of Anasi in Bermuda is to speak of a secret. To speak of a tension and rupture in her native land’s connection to its folklore tradition. A place already with its own folklore, immortalized in Western literature as “still vexed Bermoothes”—the island’s vexed state speaks of white fear, of Bermuda’s topography, but in this case we’re speaking about the memory the island and its inhabitants hold, and how the system of colonization tore the thread of identity, creating a “willing forgetfulness”.

“Bermuda is a really strange place when it comes to anything that’s Caribbean. It’s set in [to the point] where it’s generational, it’s multi-generational, it’s ancestral,” Yesha says. “We have a tenuous relationship with the Caribbean and we don’t like to acknowledge our relationship with [it] based on our colonization and how our enslaved people were spoken to, regarded, what they were taught, and how we carried that through each of our bloodlines. So when it comes to our Caribbean-ness, as part of the Caribbean diaspora, we tend to have gaps with it, and Anansi is a really big gap for me.”

For Yesha to embody the role and responsibility as a poet and writer, she had to repair that gap—a gap created not by her own doing—and despite having paternal Jamaican grandparents, the Anansi stories were not “intertwined into the fabric of [her] upbringing”. The gap started to close with the words of Zadie Smith, where she saw herself reflected at a distance, and of Junot Diaz, where his words sounded like her home and hand. These reflections of language, place, scenario, and body back to her are similar to call and response.

“I remember learning about Anansi as a kid but it was unconnected to the tradition of writing. As I developed my lane as a writer it was easy to say I’m a Bermudian writer, and that’s my immediate tradition, but the Anansi tradition is a part of another tradition—Caribbean writing—and I have to learn about that lineage because these are my ancestors.”

Tracing her finger along the fault lines of the gap to find more points of reconnection became easier as Anansi revealed himself to Yesha, “deep in the fabric of matriculation [of literature] and not [just] anecdotal in my particular upbringing”.

Yesha claps her hands together twice when she begins to recall where and when she heard her first Anansi story.

“I think at the time I was probably in primary school and everything was [about] morals, moral stories, and pushing morality at us when we were really young. I was learning about ‘The Hare and the Tortoise’ too and don’t forget, never forget Bible school, every Sunday [we were] in that Sunday School learning about damn morals. I was a kid that thought a lot. I think everyone thought I was sad, but I was really thinking, and I couldn’t tell who was bad and that was a really important thing when I was a kid. You had to know who was the bad person in this story? My brothers were gassed about Star Wars, Ninja Turtles, and it was really easy to figure out who the bad guy was in [those] things. I think [hearing Anansi] was my cognitive awakening to balance possibly. I remember thinking I don’t know who is supposed to be good here because both of them did a tricky thing.”

Looking back at both the interaction and the story through an older lens, the innocence of it is at risk of being lost when seen as a targeted project of morality, which Yesha connects to an extension of colonial rule and state policing of black bodies on the island during her childhood in the 1990s. The Anansi stories through this lens are not mere magical folklore, but propaganda, as “Black people at that time in the ’90s were trying to corral young Black people” with incessant stories and messages of “make sure you do well, [and] make sure you know this” with particular “folktales that were put through the lens of Christianity [resulting in them] hav[ing] a certain bend, a certain perspective that even if slight it’s still there, it’s still prevalent.”

What’s “still there”, and what is still evident, is the depth of influence the island has held on to, and the vestiges of colonialism and Christianity that influence how Yesha experiences her day-to-day as a queer Bermudian woman now, “coming back to home as a queer person in this island and trying to feel safe [while] looking at a country that has the most churches per square kilometre in the world.”

The elder who gifted Yesha with the Anasi story is as significant as the tale itself which Yesha latched on to, as the telling was an act of intervention disguised as a small act of kindness. “As an older black librarian seeing a young black kid in the library in 1994 in Bermuda in a country that wasn’t literary-inclined, to me that’s like ‘Let me hit you up on game real quick. You need to know something that you don’t know.’”

Maybe we won’t have to do much more than close our eyes, reach within, and remember our story. And then share it out loud and let it move through us as we pass it on.

As a self-proclaimed “smug and precocious kid” who read voraciously (albeit it predominantly white narratives such as The Boxcar Children), forever curious and proud, she was taken in, which signifies another fixed rupture of the gap between young and old.

“I’ve always been a person who loves comfort from an elder. I love counsel, I love tutelage. If we jump 10 or 12 years in the future [from that moment in the library], my mom died when I 19 and since then I gathered every older woman who would take me, I collected them to make myself some guardians. I’m a person who responds to energy from an elder, so I was never a dismissive kid. I would [think] you’re older than me, you must know something, give me some wisdom. [Hearing that story] I’m pretty sure I felt special, like I knew something that was important and that someone took time to tell me, that maybe I was supposed to do something with that information, and I still feel that way. I still have elders that I reach out to and say ‘I appreciate the time you invested in me and I hope to God I do it justice. You planted something, you afforded me some grace, and I hope that I do what I should with it.’”

The project of Anansi and folklore in the context of Bermuda is a project of repair. In her position as Lecturer at Bermuda University, she works to reclaim the history of folklore, thus changing the cannon, thus solving a rift in time.

“Now what Anasi has come to represent to me, because I’ve done my own research, my own post-colonial [research]. My life has taken a complete thread in this direction, of the Caribbean diaspora, of folktales, of mythology, of history. How it intertwines in our lineage, in our bones, in our blood. This has become my life now, and I think I’ve found how Anansi shows up in Bermuda—directly. When I’m writing this without saying it’s Anasi, I am invoking Anasi into my particular writing. Where it shows up [on the island] is before a hurricane here, if it’s coming close under a hundred miles of the island, the spiders start to weave low webs. The webs start [off] being higher in bushes, in trees, up on door jams and [then] they start to become low to avoid the wind.

“There’s a few important things that happen [like this] in which the country prepares itself without us. The fauna, the flora prepare for a storm and I think that’s the most ancient thing that happens here. Bermuda has a lore, a history, a mythology attached to it long before people decided to come over here and fuck around with it. Bermuda is still vexed. Bermuda is bewitched. Bermuda is haunted. This angry little island, this island of tempestuous seas, is the reason William [Shakespeare] wrote The Tempest. I think hurricanes, tempestuous nature, that’s the most ancient thing of us, I think that’s our true ancestors. And, if that’s our true ancestors then everything that is happening on this land is our ancestors too. If a spider is making a low web, before a hurricane—every time! What is that if not, like ancestral? What is that, if not, if not tradition? What is that if not, like a reflex, or a learned behavior because we do the same things. We just do it in a different form. We get wood, we board up and tape our windows. We bring everything inside and we make our webs really low to avoid the wind. It’s wild. So that’s how I feel like I invoke Anasi now. I really do and I write about it all the time. If you ever see me writing a hurricane piece, a hurricane poem, there’s never a time when I won’t mention spiders making a low web.”

At the start of our exploration, we worried that perhaps we were the generation at risk of letting Black folklore slip away from collective consciousness. We wondered if we’d call this piece: “Why is nobody talking about Anansi?”

Thankfully, we were wrong. Because Black folklore perseveres.

As a genre, it manages to be simultaneously a vessel and an anchor for the wider diaspora. It plants roots of identity, connection, and belonging while traveling across cultures, generations, and planes. The idiosyncrasies are part of our oral literary tradition. It’s proverbial, it’s idiomatic, it’s continually in motion and never fixed.

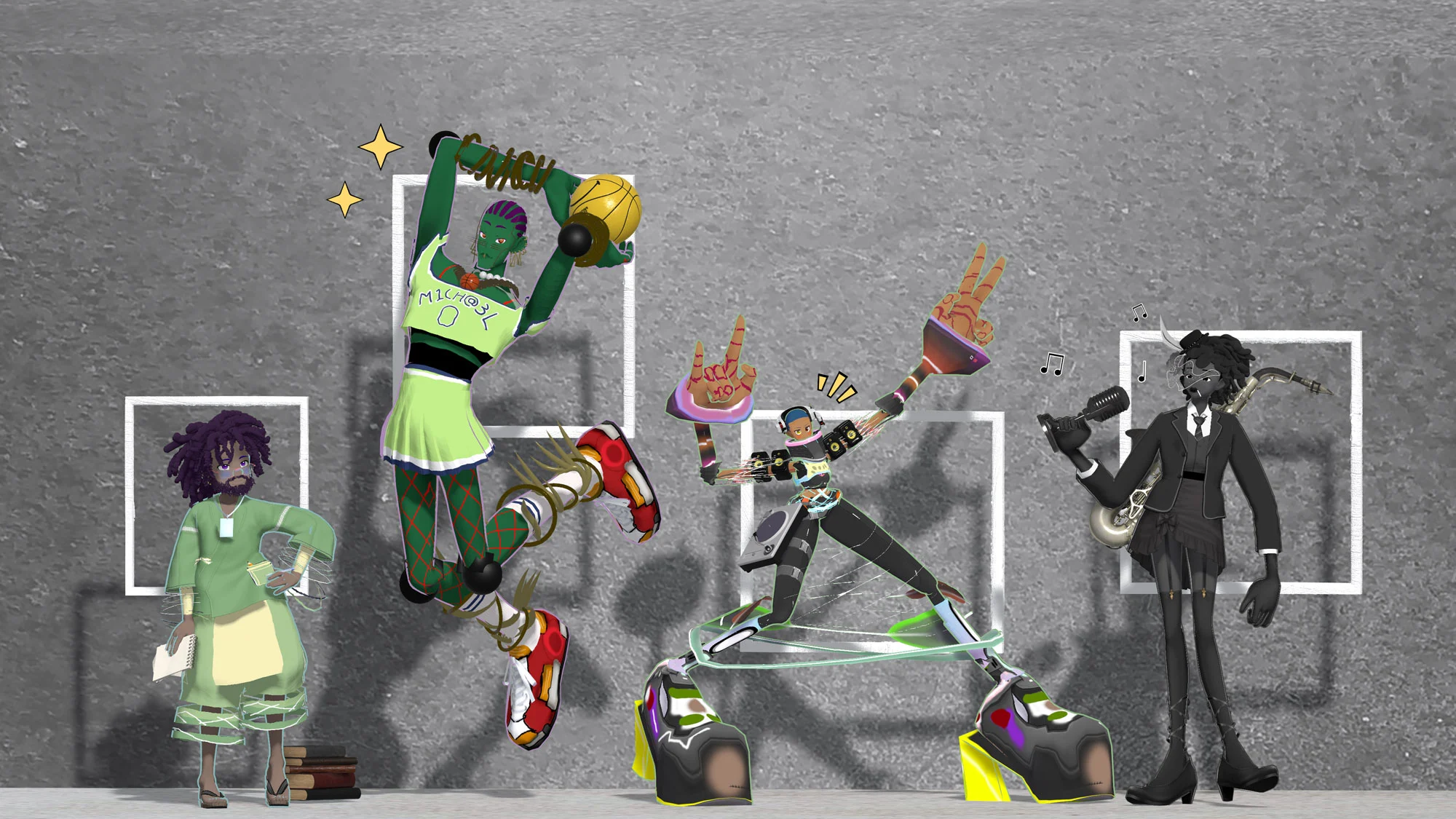

Black folklore has never been—and never will be—contained by lateral conceptions of space and time. Finding home in everyone it moves through, it will find a way to do what it has done for generations: persevere. It will continue to journey on through storytellers, in kitchens and on stages and in books and on TV and online and in comics and in ways we can’t yet imagine.

Maybe we won’t have to do much more than close our eyes, reach within, and remember our story. And then share it out loud and let it move through us as we pass it on. The act of remembering the story can be passed down, up, and alongside generations seamlessly. Sometimes the stories we remember are not a part of the time and space that we occupy in our lifetimes. That’s powerful. That’s transcendent.