The French expression “la madeleine de Proust” describes the moment an object, a smell or something else sparks a memory of a time past. It refers to a passage in Marcel Proust’s novel In Search of Lost Time where the taste of a madeleine - an airy seashell-shaped cake - dipped in tea triggers a flood of involuntary childhood memories for the narrator.

French photographer Vincent Fournier calls his ten-year-long series Space Project his personal madeleine de Proust. It makes him feel like his eight-year-old self again, obsessed with science and space. The project reminds him what it was like to imagine the future as a child.

The project began on a dormant volcano in Hawaii where Vincent shot the telescopes of the world's largest astronomical observatory, Maunakea. Since then, he has traveled to French Guiana, Chile, Israel, China, Kazakhstan, Japan, India, Russia and the US to photograph space centers, classrooms, museums and observatories which tell the story of the past, present and future of space exploration.

Vincent writes and calls the facilities, some of the best protected in the world, to let them know about his ambitious project. It sometimes takes years to negotiate the kind of access he needs, beyond the threshold where the public would be permitted to set foot. “I never give up,” he says. “It seems that I haven’t been too bad at convincing them!”

Once inside Vincent can be given anywhere from one day to just ten minutes to get the shot. It’s often impossible to prepare himself for what awaits, but he’s learnt to use these uncertain circumstances to hone his observational skills and his talent for working with available light. The result is masterfully stylized images with fluorescent tints.

Since I started this project in 2007 I have seen the evolution of space exploration.

“I have no rules really,” he says, “I turn restrictions into creative solutions. Ideas come quickly, sometimes they are memories of situations from movies or things I have seen in another context. I follow my intuition and get straight to the point.”

If you’re not familiar with the intricacies of space travel, you might not know that you’re looking at advanced science and technology looking at Vincent’s images. But luckily, his aesthetic choices make them easy to enjoy without the knowledge.

“Like with Japanese food, I like to feed the eye but also the stomach.” He leaves his images intentionally ambiguous so that other stories may arise. “My aesthetic, philosophical and recreational fascination with outer space undoubtedly comes from the pictures and books I read in the 1970s and 80s – television series, science fiction novels, documentaries and news reports – that were blended and superimposed in my memory like a palimpsest ,” he says.

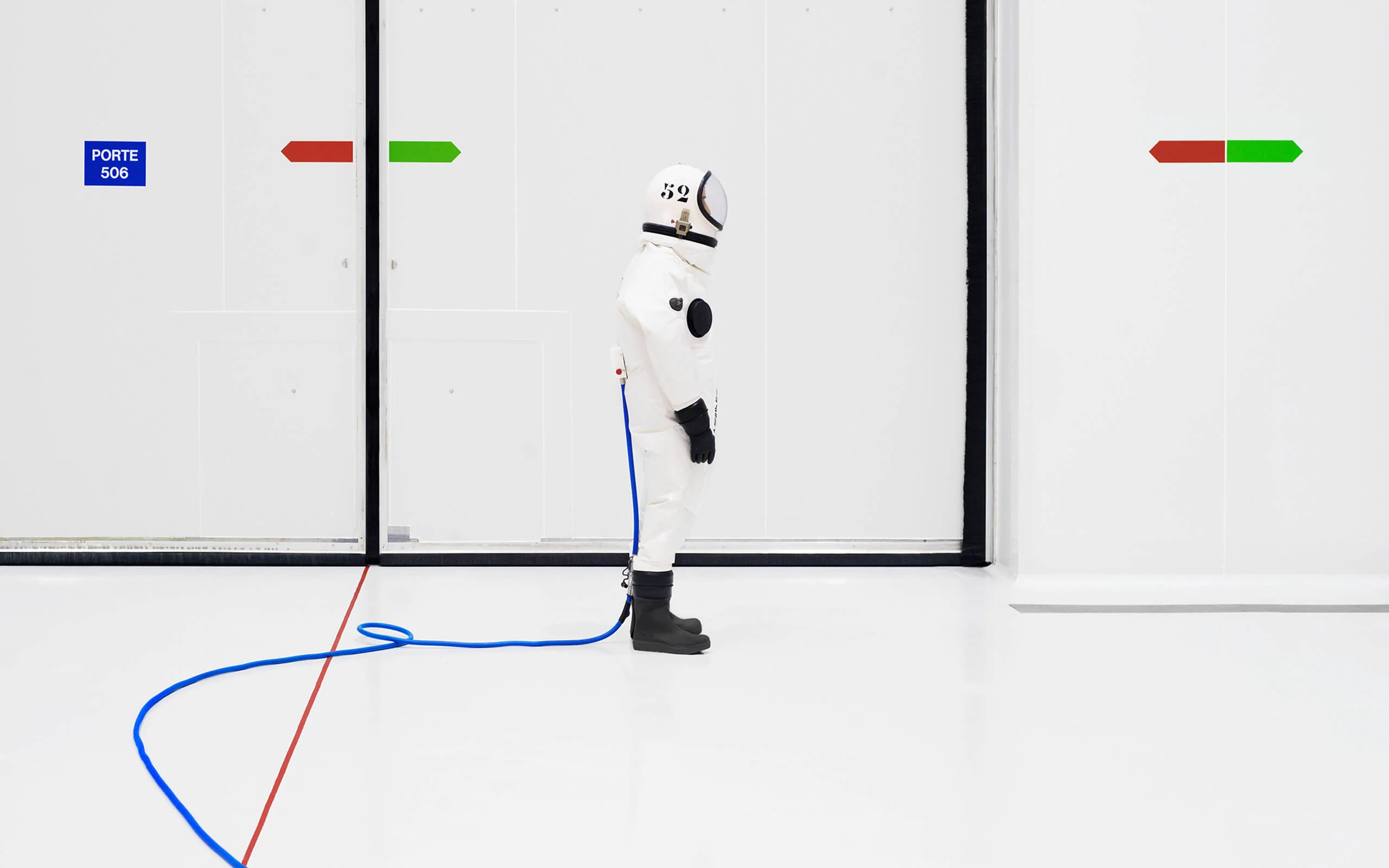

Though the bones of Vincent’s Space Project may be documentary, the meat of the series is the potential fictions that play out in the scenes. He treats the spaces he shoots like film sets, directing the story through framing or capturing a moment taken out of context with the snap of his shutter.

It’s not surprising then that one of his photos made its way into the movie The Amazing Spider-Man 2, in the form of a picture frame on the wall in the headquarters of Oscorp Industries.

“I am always staging but to a certain limit, where things are on the verge, balanced between documentary and fiction,” he says. “All the ingredients are real, but I am cooking the whole thing.”

I have no rules really. I turn restrictions into creative solutions - ideas come quickly.

In one image an astronaut in training in the vast red sands of the Mars Desert Research Station in Utah could be on a solo mission on a distant planet. In another an empty spacesuit stands oddly upright as if it might start walking. In a series shot in the clean room at Arianespace at the Guiana Space Center in French Guiana, you can imagine dramatic conversation or mundane chatter between the astronauts in space suits.

“I like to play with the tension between opposite things,” he says. “My images are playing with several oppositions: past/future, science/magic, intimacy/universality, logic/the absurd.”

On October 1st this year, Vincent released a book called Space Utopia, coinciding with the 60th anniversary of NASA. Through his ten year collection of imagery, it’s clear how space travel, and the ideas and motivations surrounding it, have changed over time.

“Since I started this project in 2007 I have seen the evolution of space exploration,” Vincent says. “It’s like traveling back in time, first to the remains of the cold war when space exploration was very linked to the military sector, then to when space travel was associated with politics, to nowadays when an economic dimension is driving the race to the stars.”

And does he dream of being aboard a rocket ship zooming into outer space one day? “I would love to have this ultimate experience,” he says, “but traveling to space is not my goal!”