Since the 1950s, hundreds of thousands of North Koreans are thought to have escaped the country. In his project UnPerson, French-Polish photographer Tim Franco takes portraits of 15 defectors who fled to Seoul. With the series now being published in a new book, Tim reflects on what he learned from their incredible stories and on how their reasons for leaving, and the new lives they made for themselves, are not always what you might expect.

Words by Alex Kahl.

In 2016, after 11 years spent living in China, French-Polish photographer Tim Franco made the move to South Korea. He’d loved his time in China but, especially after spending five years on a project focused specifically on its rapid urbanization, he felt it was time for a change of pace.

In Seoul, unsure what subject his work would take him to next, he soon noticed that the topic of North Korea was almost never discussed. “I realised that the issue was something I knew very little about, even though my house was no more than 60 kilometers from the border,” he says.

When he learned that many North Korean defectors lived in Seoul, he began to wonder about the stories they must have to tell, having experienced both sides of the divide. That was the starting point of Unperson, a project that saw Tim take portraits of 15 defectors, speaking to them about their experiences as he went.

It’s one thing to find defectors who will speak out; it’s even harder to find any who are happy to show their faces.

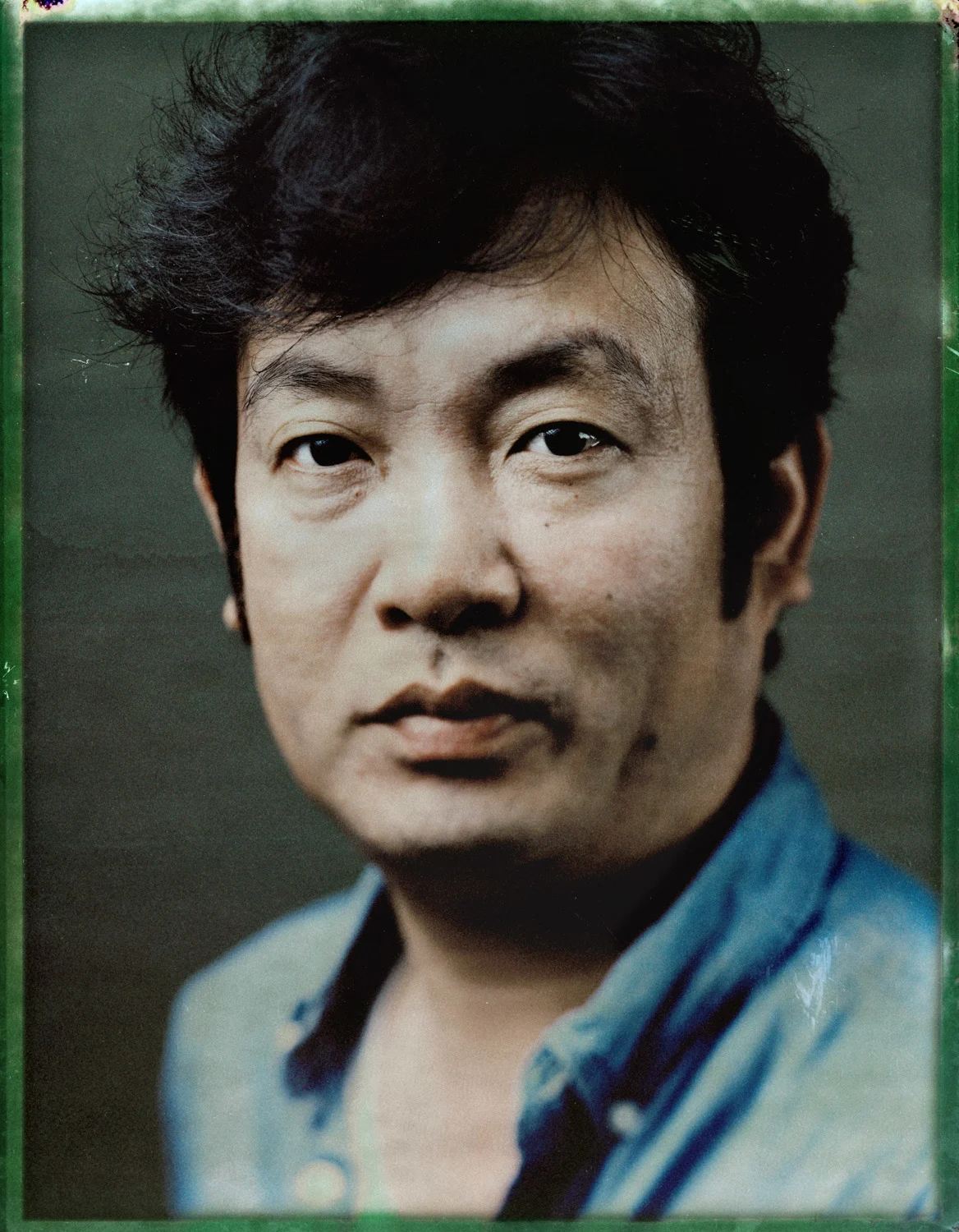

Tim wanted the project to be made up of portraits that revealed the unique stories of their subjects. When shooting with a large-format camera, you’re left with a Polaroid-style photo with a negative attached to it. Most photographers discard the negative, which shows a faint outline of the image, because it’s pretty useless. Tim had heard, though, that if a detergent was applied to it, the subject would gradually become clearer. Through this process, Tim could expose, or reclaim, something that was not supposed to exist.

“I thought this was a beautiful way to capture the fact that these North Korean people are not supposed to be here in Seoul. They should never have been able to escape,” he says. The reclaimed negatives would be riddled with imperfections due to the chemicals: covered in scratch marks and blotches. For Tim, these marks were evidence of the change the negative had been through, and reflected the long, arduous journeys the defectors had to make to reach Seoul.

After speaking with so many who had fled their home country, Tim became familiar with the different routes of escape, and he visited many of the most common pit stops, photographing the landscapes as part of the project. “I thought it was fascinating that they went through so many different environments and climates,” he says. “Most of them started at the border between North Korea and China, which is freezing, snowy and desolate. Then they reach China which is a dense, busy, super-urbanized landscape.” China doesn’t recognize the status of North Korean defectors, and so even once they had managed to cross the border, they couldn’t feel safe for some time. Police would be on constant lookout for escapees, and Chinese citizens are offered a financial reward if they report a defector to the authorities.

“From China, some of them go all the way to Thailand, crossing the border with Laos, Burma, moving through these tropical landscapes the likes of which they’ve never seen before. Some travel through Mongolia, so they have to cross the Gobi desert at night,” Tim says. In the book, the photos of locations are captioned with a number, showing the distance each one is from Seoul. These captions are a reminder that, strangely enough, the defectors must get ever further away from their destination in order to reach it safely.

Tim spoke to each of his subjects about their journey, and he told these stories on the page beside the portraits. He wanted to debunk myths and misunderstandings about this subject that so many know little about. The most interesting and surprising differences between the defectors’ stories come in their reasons for leaving North Korea. It’s easy to presume that each of them left due to immense hardship, but it’s not that simple. “When I started this project, I was naive, like a lot of people are on this subject, and I thought that all the defectors would have left because they had nothing to eat, or because the regime was appalling for them to live in, but the reasons vary. Some left a fairly comfortable life in North Korea,” Tim says.

Han Song-i lived a privileged life in the northeast of the country, for example, and when she decided to leave in search of stardom, her family’s wealth made it an easier journey than it was for most. For others, the decision to leave was made in very different circumstances. Ahn Myeong-Cheol fled desperately after his father was caught speaking negatively about the regime, and died by suicide to avoid arrest. When he heard of this, Ahn fled the camp immediately, driving to the Tumen river still holding his rifle, and somehow completing the harrowing 30-minute swim to China.

They’ve lived their whole life with these communist values, and they find it hard to adapt in this competitive market.

Regardless of their reasons for leaving, arrival in South Korea didn’t always mean that life became immediately better. The two societies are immensely different and, although that difference is often the reason behind the choice to flee, it can also be an intense shock to the system. “Many of those I spoke to found it very hard to adjust to the capitalist system when they escaped. They’ve lived their whole life with these communist values, and they arrive in this competitive market that they presume will be idyllic, but some don’t find it so easy to adapt,” Tim says. “Some felt that although they couldn’t count on the system in North Korea, they could count on the community, that people would always be there for them. Then they come to the south where things are different, and a lot of people don’t even want them there.”

No two defectors have the same story to tell, whether asked about their life back home, their journey, or how welcome they were made to feel in South Korea. What Tim’s project does is highlight just how huge the spectrum of stories can be in this complicated web. UnPerson shows 15 examples of this fascinating decision so many feel they have no choice but to make.

Purchase Unperson: Portraits of North Korean defectors here.