For much of her life, Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi has felt a sense of “otherness.” Growing up in New York with her father in exile from South Africa, or feeling out of place studying on an arts program at Harvard, she’s always been aware of the way black artists are expected to create work that has their own identity as the main topic of discussion. With Gymnasium, she’s created a series of paintings that not only deals with issues surrounding the black body, but also with other subjects she’s passionate about, from architecture to performance. She tells Alex Kahl about how the series came about, and what it means for her work to branch out into themes that she’s not expected to explore.

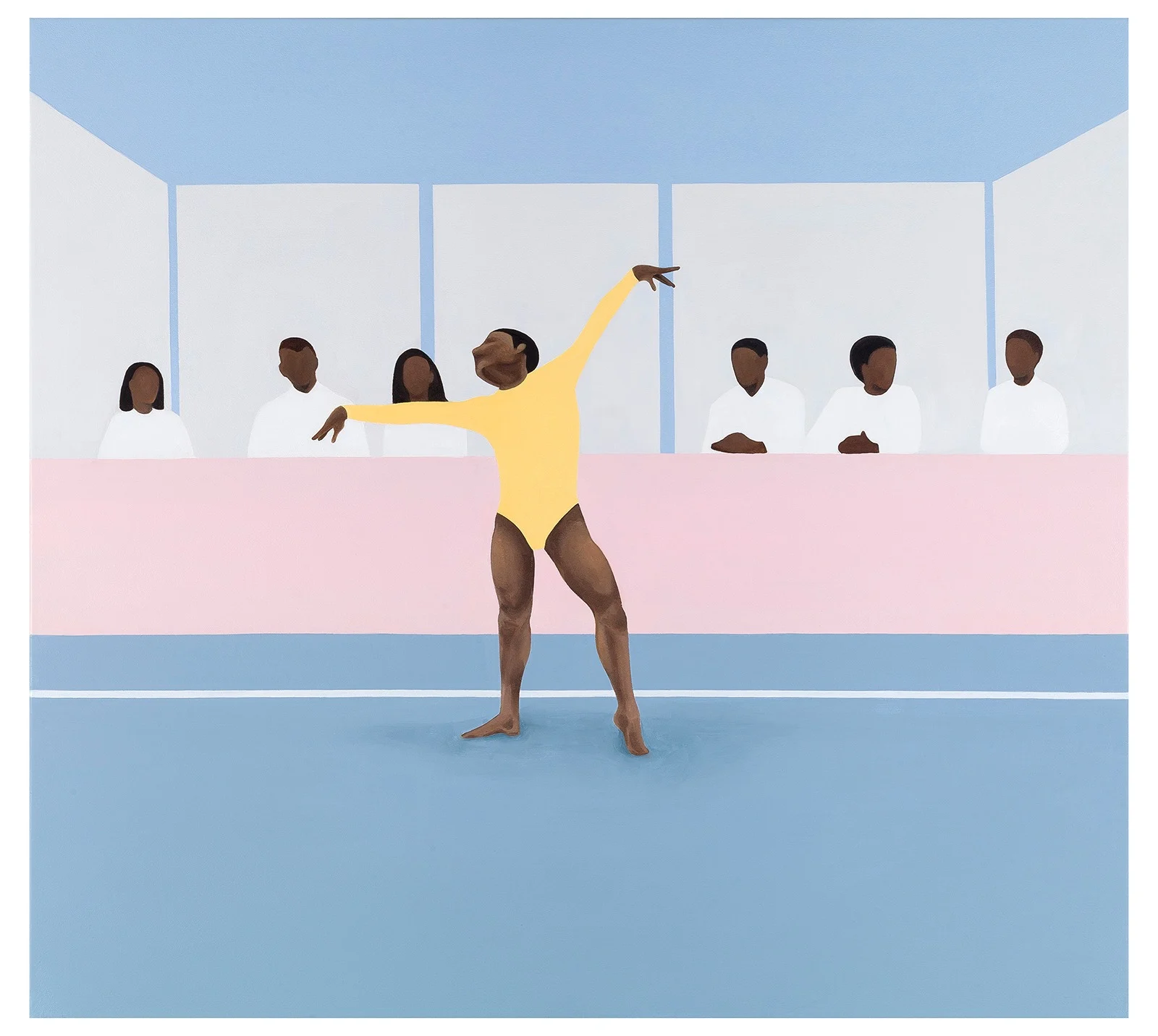

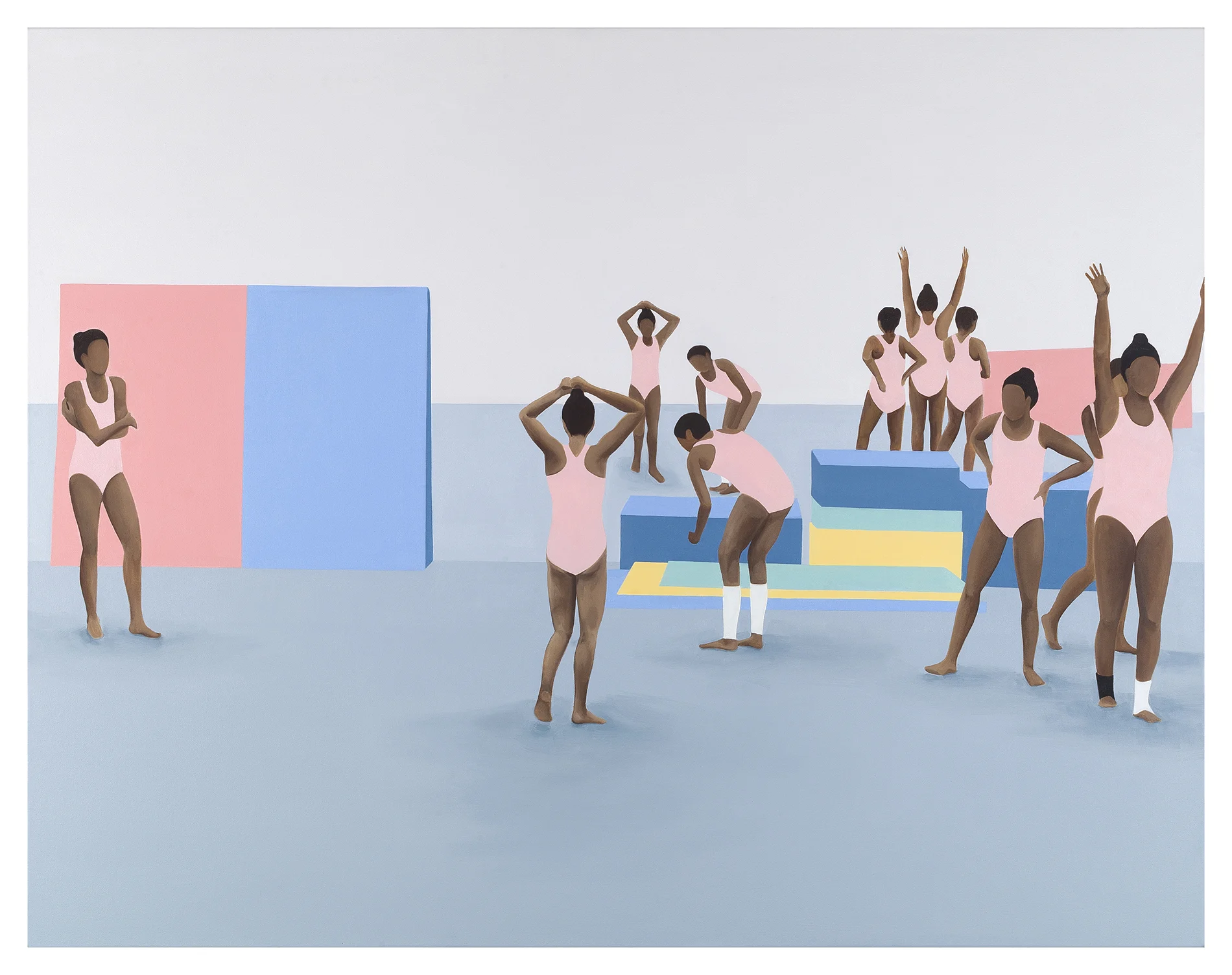

“What happens when the black figure is no longer in the image? Are you still interested in me making this work?” painter Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi asks. Her series Gymnasium is about blackness, yes, but it’s also about architecture, history, geometry and performance. A found photo of performing gymnasts sparked her interest, and she began to paint it. Thenjiwe was fascinated by the relationship between the space and the gymnast and by how one informs the other. “It was like a formal sort of interest at first, in how these two things might work together and how the figure could activate the architecture and vice versa,” she says. She painted two of these gymnastics scenes, before leaving the topic and moving onto something else.

In 2018 her partner reminded her about the gymnastics paintings, and suggested she go back and take another look. Looking back at the two she had done, she saw them in a different light. She became excited about them again, and began work on what became Gymnasium. “I saw what I had actually done; reimagined the people in those original photographs as people of color,” she says. This hints at another meaning the project has for Thenjiwe, as questions around race and identity have been at the forefront of her mind from a young age.

“I was born in New York and the story I usually tell – well, I guess the story I was told – is that I was born into exile,” she says. “My Dad was in exile from South Africa – he was a member of Pan Africanist Congress and the narrative around my family was that we were in the US waiting to go home. So, that was the narrative, that South Africa was home and that we were going to come back as soon as we could. There was another home, another life, other family members – there was some parallel life waiting for us, somewhere else.”

It’s about what it means to be a black body in a space that wasn’t made for you.

Thenjiwe’s parents were always very vocal about how they saw the world, and this would often contradict the side of history she was learning about in school. “I knew early on that the Thanksgiving holiday was not something to celebrate, that the stories about America that I was learning in class or from some of my friends, the dominant story, maybe wasn’t the more accurate story.”

“I guess we all have to reassess the narratives we were fed by our parents and by society at some point, because the world might not necessarily see us how we want to be seen. So all of my questions around my own racial identity came up, especially living in a South Africa fresh out of apartheid. What did it mean to have an identity that didn’t very neatly fit into any one box. I still do have an idea of myself being black, but in some cases I would just be slotted into the ‘Coloured’ box, so it was just a mess to try to name oneself in that time and to have others accept that name.”

Thenjiwe went to Harvard to do an arts program, but she felt uncomfortable in a lot of the classes. Other students would talk about artists she’d never heard of. They’d talk about galleries they’d visited and about how they would go down to New York at the weekend. “It was this sweet ignorance but at the time it was also terribly embarrassing. I felt so unsophisticated,” she says. “I mean now that I can have some perspective, I grew up in a totally different context – I think I was the only kid who hadn’t done all their growing up in the US. There was just a lot of catching up to do, and I had to find work that spoke to me, and that was relevant to me and to my experience. That also took some time.”

Thenjiwe has often felt a sense of “otherness” in her life. Gymnastics, and sport in general, seems to be a fitting topic through which to explore these issues of identity. The sport, like many, has historically been dominated by white athletes. “It’s about what it means to be a black or brown body in a space that was not made for you or didn’t imagine you being there, and didn’t imagine you excelling there, and didn’t imagine you redefining that space,” she says. “And that’s been part of my life experience – being the minority in spaces that didn’t imagine me being there or necessarily want me there.”

Thenjiwe also feels that on top of this, she’s exploring the way that black artists and performers are often expected to make a statement about their being black, about their identity, through their work. “You’re expected to perform your own identity as an artist. I mean I’ve been point blank told that ‘you should make work about your identity – that’s what people are going to be interested in,’ that I can’t just be interested in architecture, it has to come back to my identity,” she says. “And of course, it’s true that when you make anything, it of course relates back to who you are, but I think white artists are never asked explicitly to do that work or get put in the position where their work is only valid if it speaks from this very subjective point of view.”

Thenjiwe found the artists for her, from Kara Walker to Lorna Simpson and, later, Lorna’s former partner, James Casebere. James creates architectural models before flooding them with water. His work is often eerie and it explores the relationship between architecture and the space around it. Inspired to explore architecture more, Thenjiwe painted Pretoria’s Voortrekker Monument, and her lecturer Martin Maloney, who had always been very hard on her, was full of praise for the first time. From then on, many of Thenjiwe’s early paintings were architectural works, and separate from these, she would paint portraits of famous figures she loved. Paintings of environments and paintings of people would rarely overlap for her, but she was keen to find a way to bring the two together. This is when she found the image of the gymnast performing, which sent her off in this new direction.

It’s not only the gymnasts – it’s the audience, the judges, it’s the world.

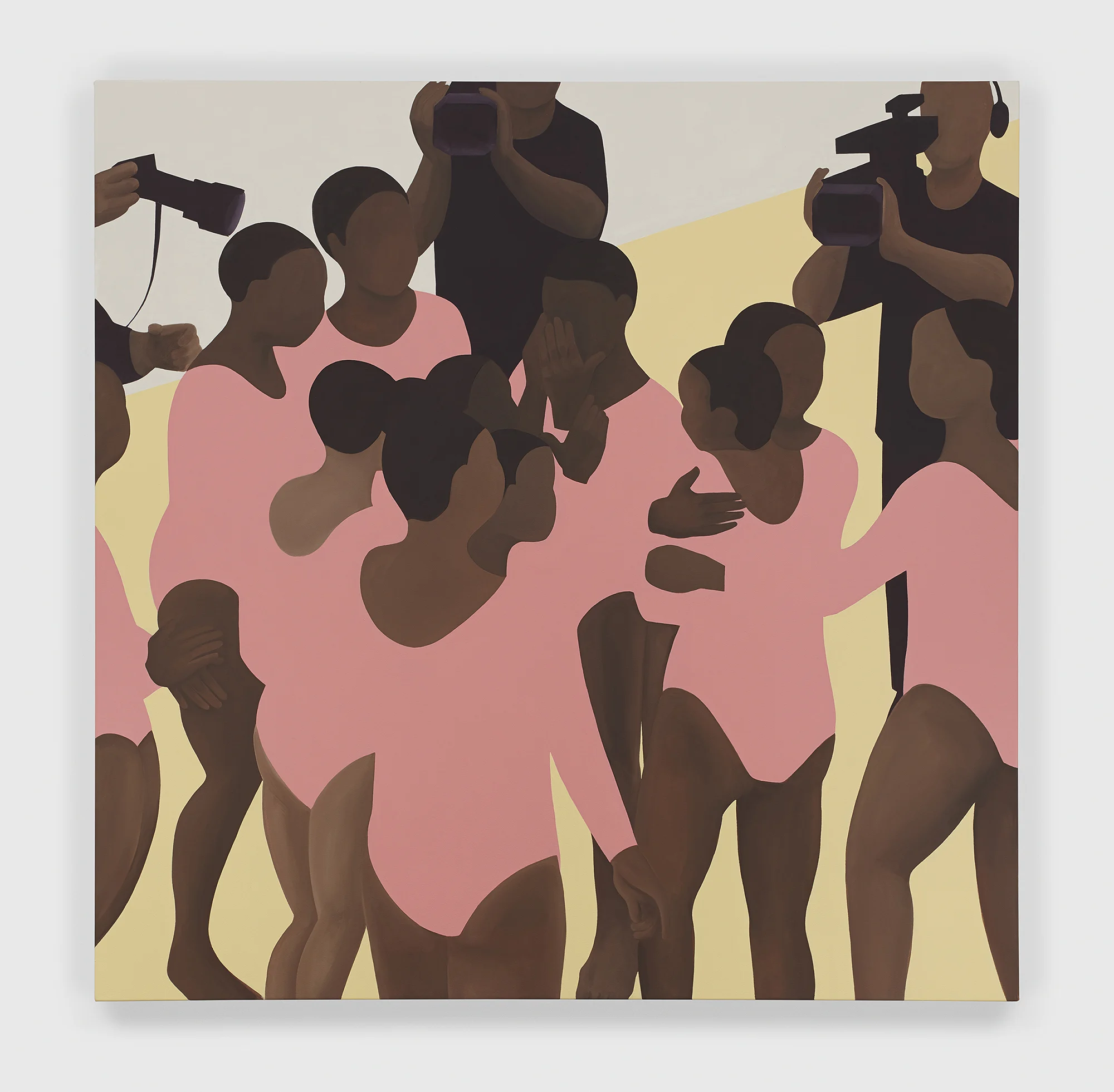

In Gymnasium, Thenjiwe also enjoyed exploring the more general act of performance. Something she knows as an artist is that performers such as these gymnasts will be watched and spectated regardless of whether they want to be or not. “It’s not only the gymnasts – it’s the audience, the judges, it’s the world. I wanted the gymnasts to look like they’re posing for a portrait in a way, but they’re also being watched by the crowd and evaluated by the judges. I wanted to explore what’s in that gaze,” Thenjiwe says.

In one piece, titled Team, multiple cameras can be seen in the image, their lenses fixated on performers standing in a group. “For me, they’re so vulnerable, and I hope that if people can see the way these three cameras are unabashedly intruding on this very tender moment, they might ask themselves how their own gaze might be felt,” Thenjiwe says. “And for me it’s important to remember that you’re looking at bodies, and you’re looking at bodies of young women.” It’s hard to tell if the gymnasts in Team are celebrating or consoling each other, but either way it’s a poignant part of a series that asks questions about how just performing their craft can make these athletes so vulnerable to scrutiny and judgement.