Let’s face it, it’s tricky to find a job that doesn’t require us to spend an extraordinary amount of time staring at a screen. But more and more people are choosing to spend a chunk of their time doing something hands-on, to give their brain a bit of a break from the blue light. Here James Cartwright explains how professional baking saved his career, and speaks to others who have pursued dedicating a chunk of their working week to a fulfilling craft that makes them happy.

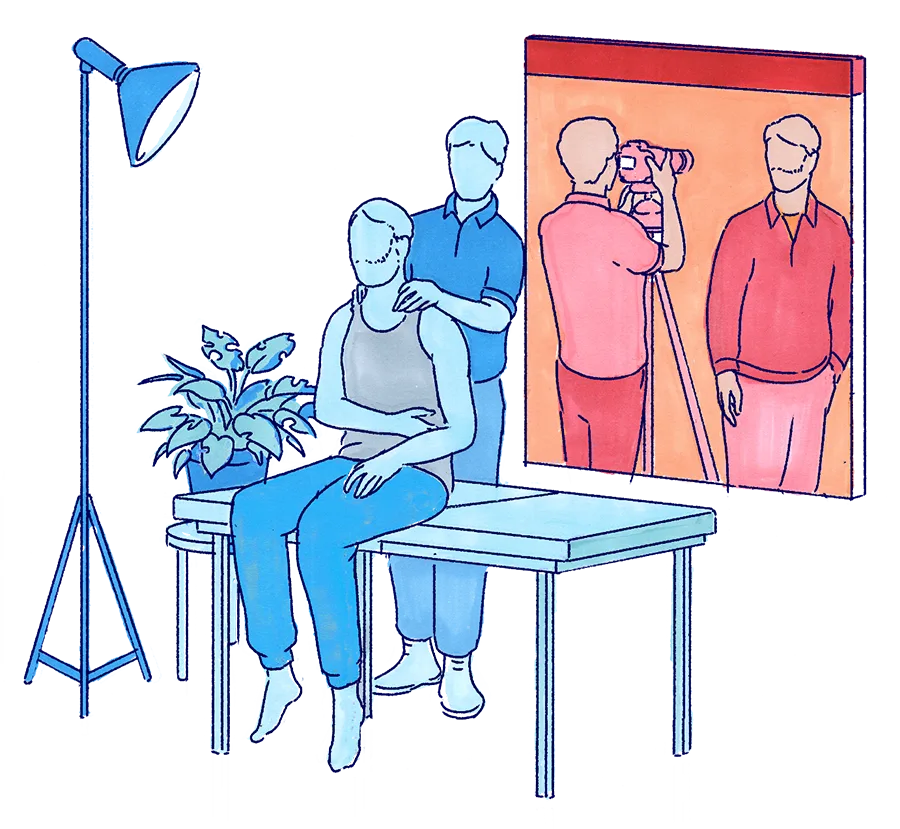

Illustrations by Liam Cobb.

I really want to be a baker. I feel a certain discomfort admitting this because in the last few years baking has mutated from a late-to-bed, ealy-to-rise, humble-but-skilled profession into a purely aesthetic Instagram trend in which staple food meets pornography and everyone with a sack of flour and some yeast is chasing a money shot. (Instagram cheapens everything). That’s not the kind of baking I mean. I’m talking about rising before dawn, spending all day engaged in strenuous manual labour, perfecting a craft, understanding and feeding a community, then going to bed physically exhausted each night with a stomach moderately full to stuffed with pastries.

For someone who’s written words for a living for nearly 10 years, baking scratches a particular itch that my day job rarely does. Flexing my brain to deliberate over syntax and conjure engaging article structures certainly has its perks, but I can’t help but feel that my body is going to waste as I sit here typing, my shoulders hunching ever closer to my keyboard as my arse and chair achieve perfect symbiosis. Another less than ideal quirk of my job is the persistent solitude. Most of my days are spent alone, some lonely, and while much of that time is filled with interviewing people and probing them about their lives, they’re still just strangers to me; an atomised group of individuals spread across the world. Nothing at all like the community I crave. Nothing at all like my old work friends.

As with anything that’s pursued five days a week, it does have a tendency to get a bit boring.

It may sound like I’m in crisis, but I like what I do for a living. Sometimes I really love it. But as with anything that’s pursued for 10 hours a day, five days a week, year after year, it does have a tendency to get a bit boring.

In 2016 I was probably a little bit more in crisis, and while researching a magazine about food systems (it’s very good, you can find it at weaponsofreason.com) I decided that the best possible way to understand food production properly was to go and work in the industry. It was also a great excuse to try something new and break up the monotony of a period of career funk. I’d been making bread at home for a good few years and had recently taken a course in advanced bread techniques (that’s right, advanced, you rookie gluten pornographers!) but I wanted to do more than just a few loaves a week. I asked the folks who ran the course whether they needed an apprentice. They didn’t, but I managed to persuade them to take me on.

For three months, every Wednesday, I would arrive at their tiny bakery before dawn to mix dough, shape loaves, fuel and stoke the wood-fired oven to its optimum baking temperature, never once getting to see a finished loaf of bread because the bake happened the following morning and by then I was already back at my desk. I loved it. Wednesday became the highlight of my week in spite of the 5am rise and two-hour drive to my new place of work.

For various reasons (I don’t think it was my fault) the bakery shut down just as I was hitting my stride. I was heartbroken. My regular routine no longer lived up to the varied pattern I’d created for myself. So I stalked the bakeries of the south west of England and waited for an apprenticeship to appear. Six months later it did, and instead of just one day, I began working between two and four days a week at another, larger bakery and cafe. I made hundreds of loaves of different types of bread each day. I learned to make light, buttery croissants, crisp pains au chocolat and cinnamon buns the size of my head. I lugged crates of dough around, shaped pizzas for the lunchtime service, delivered ciabattas to local restaurants, put on muscle, gained fatty waist inches and was perpetually covered in flour. It was even better than the first time.

For a while I worked six days a week baking bread, writing articles, and editing books and magazines, and as far as I’m concerned this seven-month period was the apex of my professional life. Juggling two jobs that both gave me different kinds of satisfaction wasn’t without its difficulties, but to me it was perfect, and work may never be that good again.

I worked six days a week baking bread, writing articles, and editing books and magazines.

I gave it up when my partner and I decided to have a kid and realised that maternity pay and a baker's wages don’t easily cover rent, bills, nappies, onesies and all the other accoutrements of parenthood, and getting up before dawn when your baby won’t sleep through the night is really the worst form of masochism.

While my double life has been temporarily put on hold, I’ve often wondered if there are other people trying to maintain two careers at once, or attempting to segue from one to the other without going back to full-time education. I didn’t have to think too hard or look too far to realise I’m not a rarity at all.

My good friend and occasional collaborator, Jasper Clarke, is an award-winning freelance photographer with clients like Vogue, AnOther, Paul Smith and Converse on his books. For most of the time I’ve known him, he’s also been retraining as an osteopath and since getting his BSc in 2019 has been practicing in London and Bath.

Like me, Jaz has found that freelancing can be a bit of a downer sometimes, and working for yourself doesn’t lend itself easily to making lasting connections with people, or even getting much feedback about your work, positive or otherwise. Freelancing can be pretty thankless. In addition he believes the folks who commission photography aren’t particularly imaginative, which can really take the fun out of making work.

“I’m a person who’s interested in loads of different stuff,” he says, “and I thought that if I showed enough technical proficiency then people would commission me for all sorts of work. But that’s not the way it works. People basically want you to show them that you’ve already taken the picture that they want and that frustrated the shit out of me.” So he decided to change things up and started to retrain part-time, which took some guts.

Jaz left school at 13 with no qualifications, did an art foundation in his early twenties (he got a distinction) and sacked off his photography BA at Edinburgh Napier because he was already making a living shooting stories for BMX magazines and “the lecturers were all a bit ponderous and annoying and I thought ‘fuck this shit, I want to earn some money.’” He assisted some extremely reputable photographers for a few years and then struck out on his own.

“But I started to feel like maybe I wasn’t as well educated as other people and maybe my thinking wasn’t as sophisticated. And that’s really why I started to think that I’d like to go back into education. It was quite a powerful feeling, actually, that I needed to train or educate myself in some way in a science or health field. It had been there in my mind for a long time that it was something I wanted to do.”

He had to start again from scratch, “at the monkey stages, doing science for dummies at The Open University one year, then a qualification in anatomy the next year. The year I started my osteopathy BSc I actually got a photography agent for the first time.”

Nine years after striking out on a new career path, Jaz is finally juggling osteopathy and photography at the same time, but it’s all very much a work in progress. “I’m still holding out hope that my big dream of moving to the West Country, having a cheap mortgage and being able to manage photography projects and practice osteopathy is all gonna work out.”

I started to find working in front of a screen all day hard going on both my mind and body.

Around the same time that Jaz was going back to school, illustrator Andrew Groves moved with his wife to a secluded spot in the countryside to find a quiet studio space to make work. “Inadvertently I got tangled up learning traditional green woodworking and countryside management skills and started to find working in front of a screen all day hard going on both my mind and body.”

Everyone’s path into work is different. Although the creative industries run on a bizarre doctrine that says you ought to feel blessed, privileged, nay, exalted to work within them, like any career path some of us (a lot of us) just found ourselves here and weren’t expecting it to demand quite so much screen time. The same is true for archaeologists and haematologists — the common factor that binds everyone pursuing two careers seems to be a desire to escape our desks.

Archaeologist Sarah Blacker-Barrowman spent years meticulously excavating ancient history in trenches. When injury made her job more desk-based she began plotting a new career in millinery. After 10 years in the lab, haematologist Tola Adefioye began to find the lack of creativity and independence in his day job excruciating, so he’s developed his passion for furniture restoration into a business that he hopes will support him in future. “When it does, it will be bye bye haematology.”

Should you find yourself in a situation where pursuing two careers takes your fancy, or more likely in the current climate, that one type of work can no longer financially sustain you, there are a few things you should bear in mind before you take the plunge.

Juggling two jobs is hard

I feel like this goes without saying, but equally I’ve just expended 1500 words telling you how wonderful it was to have two jobs. It was really hard. Managing the expectations of different clients and my partner felt like a full-time job in itself, and I had to get really, freakishly good at using my calendar – which I hate.

“It takes a lot of effort,” says Tola. “My day job is very mentally channelling while furniture restoration is physically demanding. Dividing my time to get a healthy dose of both is really important.”

“It can take a lot of effort to juggle the two (three, four?) sides of my work,” agrees Andrew. “What makes it challenging is the unpredictable nature of the illustration workload and the seasonality of the outdoor work; sometimes I'll have to turn down illustration work because I'm too busy with outdoor work and vice versa, and it's usually the really good projects that I have to turn down because they demand more commitment and time.”

Sometimes your careers will complement one another

Personally, baking really helped my writing, not just by giving me insight into food systems, but by affording me a different environment to work in and some headspace to think. Bread making is pretty repetitive work and I’d often find myself thinking about writing while I was shaping at the bench.

“Starting to train in these other things actually made me enjoy photography a lot more,” says Jaz, “because I always had this other thing to focus on, so I didn’t get as stressed out. Most jobbing photographers actually have quite a lot of time on their hands, so if you can find a way to fill that time and look like you’re busy then people think you’re in demand. I was just always too busy doing osteopathy to show my portfolio to people, and I think that worked out pretty well for me.”

Sometimes you’ll feel like you’re failing at both

“It can be really hard switching from one job to another,” says Andrew. “After a few days working outdoors on practical tasks it can be really tough getting the creative part of my brain working again.”

Some weeks you’ll just find you can’t get into either of your professions. One particularly bad week I ruined all the bread for a market by neglecting to check the fridge temperatures and had a couple of article drafts torn to shreds by editors. What can you do?

It’s going to cost you some money

If you’ve reached a point in your career that means you’re making a decent living, chances are that any new direction you take will be less well paid, or you’ll have to pay for it. Baking pays a lot less than writing, countryside management doesn’t command the same fees as commercial illustration, practicing osteopathy requires a lot of expensive education.

“I used part of a redundancy package to fund millinery courses at the London College of Fashion,” says Sarah, “and then set to work learning and practicing all I could.”

But the variety should be worth it

“Remember the ‘why,’ in why you want (or have) two different careers,” says Sarah. “I find this helps to get me through the tougher times and keep focused and motivated by remembering what I love about my work.”

While Tola and Sarah are definitely in transition from one career to another, they both still enjoy the variety of their two jobs. For me, Jaz and Andrew, having a permanent balance of both careers is really the dream.

“It's tempting sometimes to trade one for the other for a bit more simplicity,” says Andrew, “but I think it would be very hard to give up either in truth.”