Movies rely so heavily on a perfectly chosen actor in the leading role. Considering how important it is to get this right, the casting directors who do this are often overlooked. Here, writer Anna Bogutskaya meets some of the most crucial casting directors in modern cinema, and looks back on the people who paved the way for them.

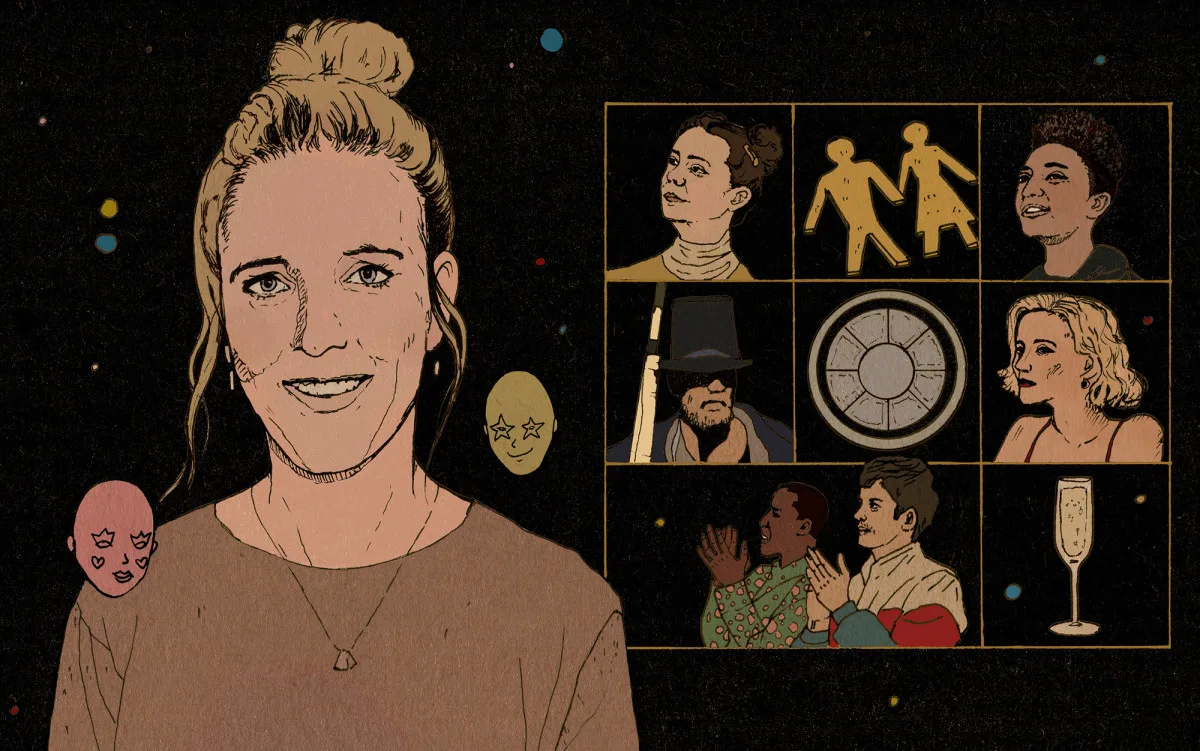

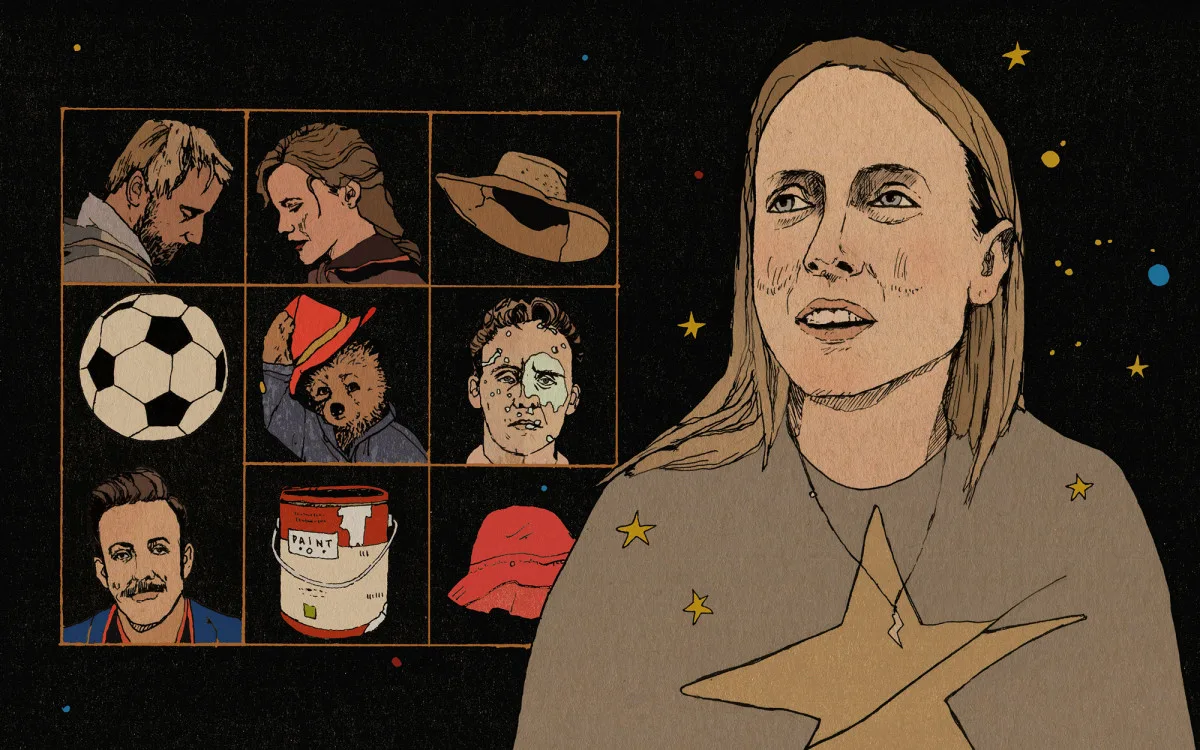

Illustrations by Toma Vagner.

The film industry is built on self-mythologizing, on creating fantastical stories about everyone having the chance to be plucked from anonymity to being immortalized on the screen, with their name in the proverbial lights. The right cast can get a film financed, generate headlines and draw in an audience to a film before a single frame is shot.

Martin Scorsese has said about his casting director, Ellen Lewis (who he has worked with consistently since 1990’s Goodfellas), that “more than 90 percent of a picture is the casting.” Yet the figure of the casting director has long been the unsung hero of the industry. Since the very inception of Hollywood, the work that goes on behind the scenes into the finding and making of a movie star has remained in the shadows. Casting in the invisible artistry of filmmaking.

While actors have been around for centuries, casting directors are a direct byproduct of Hollywood. The role of the casting director has been a vital and controversial one since the beginnings of the entertainment industry. Their work is a necessary function of the stardom machine, a go-between the producers and the talent – and yet completely unrecognized by the same machine they are servicing.

“I often find that everyone who’s on set and is physically there and visible is more easily recognized,” says casting director Kharmel Cochrane, who has cast The Witch, The Lighthouse, Saint Maud, and the recent Channel 5 series Anne Boleyn. “Everything that we do happens before you even get to that stage, but then you can’t get to that stage without us.”

Inclusivity and representation is just as important behind the camera as it is in front.

Finding the right cast for a project has become more important than ever before. Actors are paramount to getting a film financed. Theo Park, who in her twenty odd years of working in the industry has cast Paddington, High Rise and Ted Lasso, among many others, has seen a complete shift in the industry: “It didn’t used to be so important. You didn’t need to have an actor attached [to an upcoming film]. When I worked at an agency, we wouldn’t even look at a script unless it was greenlit. Now actors have the power to make a movie, to get the money.”

And yet, casting directors are still often not shown the same kind of deference as other heads of department. Lauren Evans, who has cast the series Sex Education, Taboo and The Girlfriend Experience, says that “for the longest time we’ve been made to feel like our role isn’t important. But we’re at the start of the process, and it’s almost a catalyst for all the other departments.” Theo echoes this: “Not everyone’s got an opinion about which set decorator you’re gonna use, or what wigs you’re going to use for a character, but everyone’s got an opinion about casting.”

The entrypoint into the profession remained mysterious, until quite recently. Saffeya Shebli, who worked as a film publicist before shifting careers into casting, recently graduated from the first cohort of the NFTS’ Casting course and is now working in casting at London’s Old Vic. She decided to switch careers because “casting stood out to me – it’s a creative craft that’s been overlooked in the past.”

In the Old Hollywood studio system, casting was based around fitting an actor’s looks with a type of character, with not much movement allowed. If you looked like a leading man, you were a leading man; if you looked like a villain, you’d be cast as a villain; and that’s how it’d remain for the rest of your career. Few people managed to outmaneuver this system, like Humphrey Bogart, who initially started off in supporting roles as a gangster and villain before becoming one of the defining leading men of his generation.

Before, the casting director (not yet known as such) was not a profession, it was a function – essentially HR. The contemporary idea of the casting director evolved in response to two seismic changes in Hollywood: the breakdown of the studio system and the rise in television in the 1960s. With the contracts gone, actors became freelancers, so the need of someone who knew talent was needed. And, with television productions on the rise, the sheer amount of roles to be filled demanded a different approach.

All roads point to Marion Dougherty, the woman who is credited with creating the modern contemporary casting director, spearheading the rise of independent casting agencies and discovering a long list of familiar names, like Al Pacino, Dustin Hoffman, Glenn Close, Bette Midler, Jon Voight and Diane Lane.

Marion, who is the primary subject of the 2012 documentary Casting By, is credited with changing the landscape of casting on an industrial and a creative level. Her story is the story of casting directors elevating themselves from administrative gatekeepers to nurturers of talent.

She cast James Dean and saved him from getting fired. She gave Christopher Plummer his first US acting job. She cast Glenn Close, who’d never been in a film, in The World According to Garp. She saw Al Pacino on stage and gave him his first screen roles so he could afford to continue acting. She defied the director to look beyond race and cast Danny Glover in Lethal Weapon. The list is almost endless, and at the heart of all the celebrity tidbits is a genuine love for actors that all good casting directors share.

Marion, who would open up her own independent casting agency in a brownstone in New York City, saw beyond the appearance or the audition, she looked for potential – the possibility of greatness. She kept notes on every actor she met, and remembered them. Marion saw beyond the prescriptive nature of the screenplay and instead cast for talent. And she instilled that approach in the next generation of casting directors. By design, she only hired women.

Casting has traditionally been a craft dominated by women. Professor Brian Herrera of Princeton University, who is currently writing a book about casting practices, called the casting directors a “pink collar workforce.” Casting directors are “expected to do a lot of managerial and also emotional labor both for the producers and the actors in order to be very efficient and effectively invisible in the process.” Marion’s brownstone casting office, if it had been a house populated by men, would’ve conjured up suspicion.

It’s 10 to 15 minutes of my time to see if someone has potential or skills, and maybe just never had an opportunity to be in the right place at the right time.

There is an alchemy to casting. Kharmel describes it as “corralling everyone’s thoughts and dreams into something physical.” Saffeya calls it “a direct dialog with the audience. Whether it’s a film, TV series or play, it’s the people you see in front of the camera that you’re asking your audience to connect with in some way.”

The actuality of casting involves a mixture of negotiation, maintaining relationships with agents, producers and directors, and managing all the schedules and contracts of productions and actors alike – and gut reaction. Lauren talks about being able to “piece together an ensemble, always being open to new actors, trying to keep your finger on the pulse and not resting on groups of actors you think are good.” Finding new talent, being able to see beyond the page, and beyond the current reality of an actor, and focusing on the potential, are key skills. “I love really cool, interesting faces. They might not have any credits but it’d be really good to see what they can do in the room,” says Lauren. “It’s 10 to 15 minutes of my time to see if someone has potential or skills, and maybe just never had an opportunity to be in the right place at the right time.” Being able to see chemistry and spark, beyond what’s even written on the page. Call it talent-spotting, or a mild form of obsession. If someone stands out, “I end up casting them in the next thing, that’s the truth,” says Kharmel. She got obsessed with Paapa Essiedu after seeing him in I May Destroy You, and cast him in Anne Boleyn. She remembered Morfydd Clark after she auditioned for The Witch, and kept her in mind when the time came to cast Saint Maud.

Marion’s is also the story of the lack of industry acknowledgment that continues to plague casting directors today. In 1991, there was a campaign to get her an Honorary Oscar. Hollywood luminaries, some of which gave Marion credit for taking a chance on them or directly kick-starting their career, wrote to the Academy personally endorsing her for the award. The Academy did not give her the award. She died in 2011. Lynn Stalmaster, Marion’s West Coast contemporary and equally a titan of his craft, became the first casting director ever to receive an Honorary Oscar in 2016.

The controversy around recognizing casting begins and remains around the issue of credit. There is a divide between directors who see casting directors as core creative partners and those who don’t. The first time Marion got her own title card was in 1972, with the film Slaughterhouse Five, directed by George Roy Hill, who Marion worked with several times, including casting the iconic duo of Paul Newman and Robert Redford in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, a film for which she was denied a casting director credit. At this point in her career, she’d never gotten a title card credit of her own. In fact, no other casting director had until that point.

Finding new talent, being able to see beyond the page, and beyond the current reality of an actor, and focusing on the potential, are key skills.

The sticking point, at least in the United States, has always been the Directors Guild of America, who were iffy about allowing any other role to have “director” in their title (this has since been allowed for directors of photography and art directors). Interesting, since the relationship between director and casting director is the most vital one. “My best conversations are the ones that I have with the director”, says Kharmel. The allyship that forms between her and the director on a project often evolves into friendship and an ongoing collaboration, like the one she has built with Robert Eggers, with whom she has worked on every single one of his films, from The Witch to the upcoming The Northman. “He really fought for me at a time when his star was ascending and he could’ve had any casting director he wanted. He brings out the best in me,” she says.

BAFTA only added the Casting Director category in 2020. The Academy still doesn’t recognize casting in its awards. At this time, they’re the only credited head of department that doesn’t get their own awards category.

Diversity and inclusion have become a key factor in casting, but only recently. Kharmel said: “I’ve been on some really uncomfortable calls with networks, channels and execs where I’ve been told that my casting isn’t diverse enough, but then they’re talking about a visible poster. What? So you’re casting for a poster?” Color-blind casting (also called “non-traditional casting”), is defined by the Actors’ Equity as “the casting of ethnic minority and female actors in roles where race, ethnicity and gender are not germane to the character's or the play's development”. Although it’s not in any way a new development (the term itself didn’t exist until the 1980s, when the first National Symposium for Non-Traditional Casting was held in the US), the prioritising of inclusive casting certainly is, and it’s creating headlines.

Armando Ianucci’s The Personal History of David Copperfield, cast by Sarah Crowe, had Dev Patel in the lead role, alongside other actors of colour including Nikki Amuka-Bird and Benedict Wong in roles which had previously almost exclusively gone to white performers. Kharmel’s own casting of Black British Jodie Turner-Smith as Anne Boleyn attracted a lot of attention. The list goes on, but the attention placed on the casting - and the unfortunate need of actors, directors and casting directors alike to justify their decisions to the press - is emblematic of how important these decisions are for the industry and the public alike. “The studios are really hot on it, as they should be,” says Theo, “Even 10 years ago it was really hard to get our directors to properly focus on diversity and inclusion.” There are power dynamics at play here. The history of theatre and film is rife with white actors playing characters written as people of colour. Additionally, Hollywood pundits considered it industry gospel that diverse casts would not attract white audiences. Although proven wrong over and over again, most recently by a study conducted by talent agency CAA in 2017, which showed that films with inclusive casts outperform those with all-white casts. Additionally, the study showed that almost half of the audiences who go to see a film in its opening weekend are people of colour. There is a marked difference, however, between color-blind (or non-traditional) and identity-conscious casting, which takes into consideration the intersections of a person’s identity into the casting of a role, whether it’s a traditional text or a new one.

New York-based casting director and founder of X Casting, Victor Vazquez, calls casting “a culture-making machine”. Casting feeds the industry, feeds the actors and feeds the audiences. So, acknowledging and embracing the intersections of identities of actors is paramount of creating a sustainable industry. In Saffeya’s words, “inclusivity and representation is just as important behind the camera as it is in front.”

The profession needs “more visibility and more accountability,” says Kharmel. Clearer entry points in the industry. Transparency around pay. Industry recognition. Kharmel, who came up as a casting assistant before starting her own company, has been very vocal about how much women are getting paid so that they’re not being exploited.

There is a change in the air. Theo, Lauren and Kharmel are part of a new generation of casting directors who are supportive of one another, sharing casting lists, encouragement and even jobs with each other. Casting directors are slowly making their way out of the shadows, with the industry finally catching up to the creative contribution they make to the industry.