When it comes to the history of oil, many people will think of the beginning of the oil economy in America in the 1800s as a starting point, but it’s been discovered and put to use by communities around the globe for thousands of years. If you feel like brushing up on your knowledge, then look no further than Sandra Sawatzky’s 220-foot long tapestry charting the key moments and characters in the long, winding, violent history of the black gold. Here, Sandra walks Joe Zadeh through five of her favorite chapters of the story.

The story of oil is one that seems to underpin human existence. It powers our cars, trains, planes and boats. It heats our homes and our food. It’s inside our medicines, clothes, shoes, cosmetics, containers, televisions, laptops, smartphones and sunglasses. It props up our entire global economy. “Wherever oil goes, the market goes,” wrote Peter Coy and Matthew Philips in Bloomberg. And whenever we think we’re starting to run out of oil, a new technology is invented that promises to find us more, by drilling, heating and rupturing the Earth. Around 95 million barrels of the stuff was produced every single day in 2019.

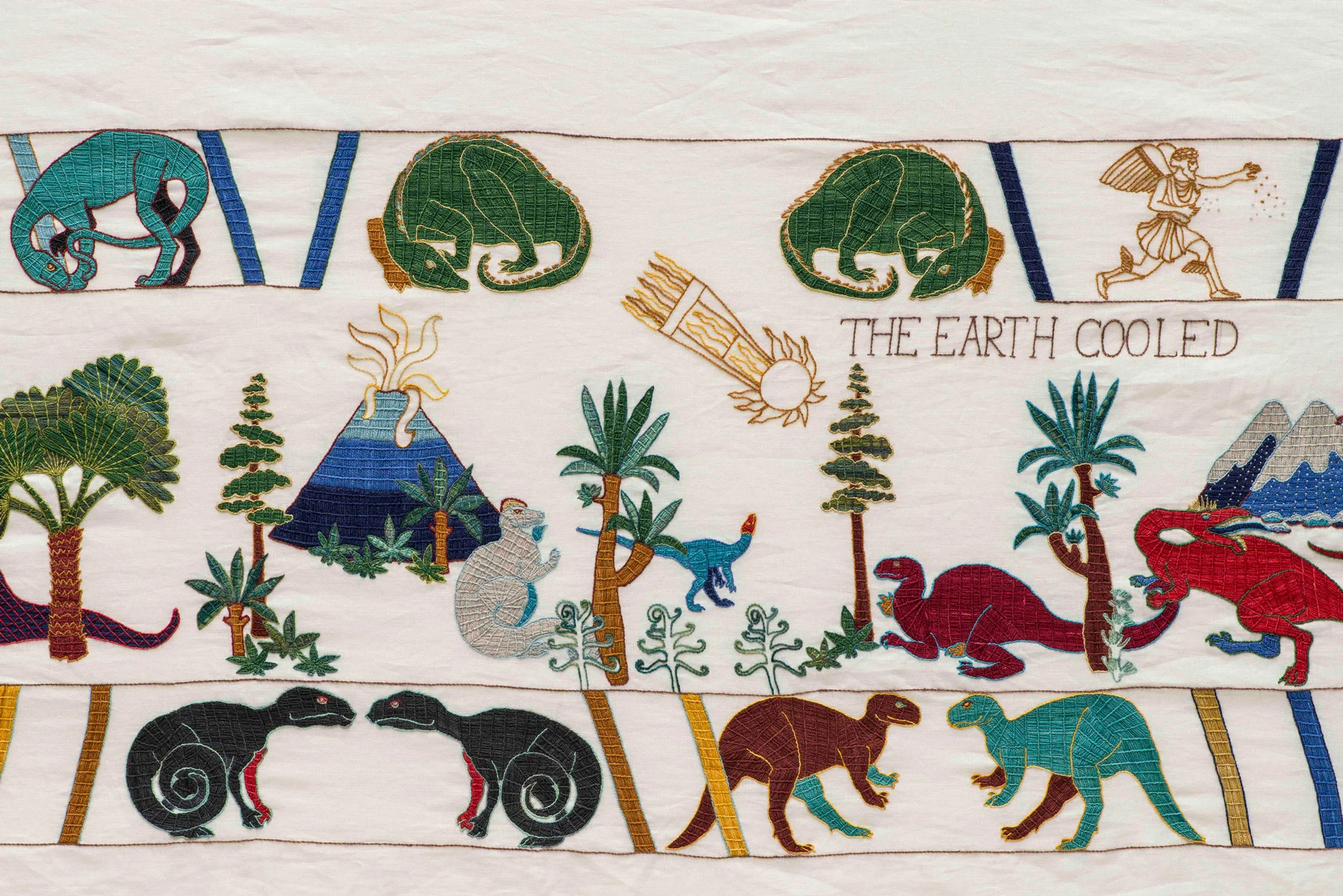

It took the Earth millions of years to make this substance which we’re just burning like there’s no tomorrow.

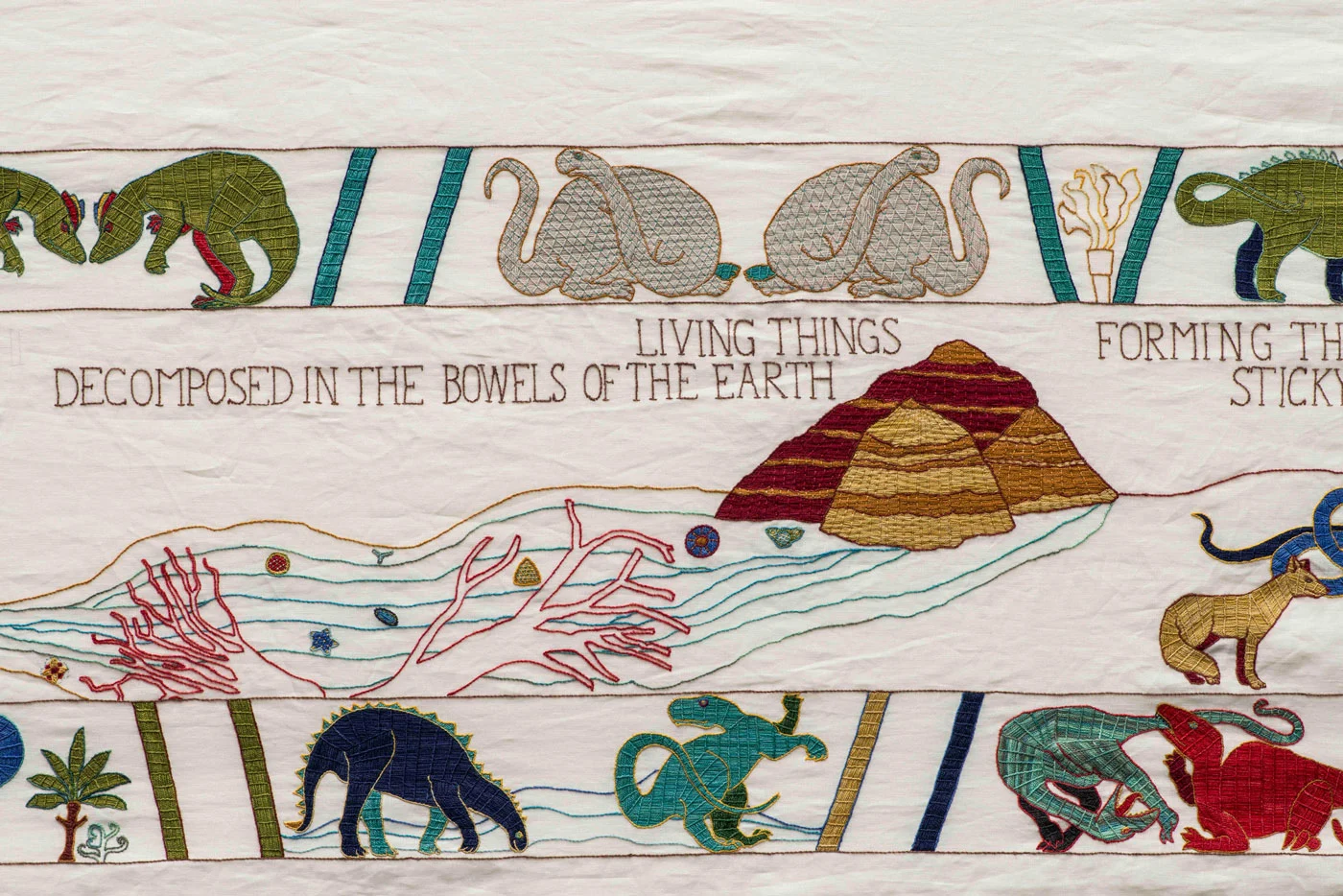

But our common understanding of the story of oil often only begins with the booms of the 1800s onwards, and its consequences for civilization. Rarely is our attention drawn to the deep history of this ancient black and sticky liquid. “It took me 10 years to make this work of art,” said the Canadian artist Sandra Sawatzky, who took on this task in her gigantic work, The Black Gold Tapestry, “but it took the Earth millions of years to make this substance which we’re just burning like there’s no tomorrow.”

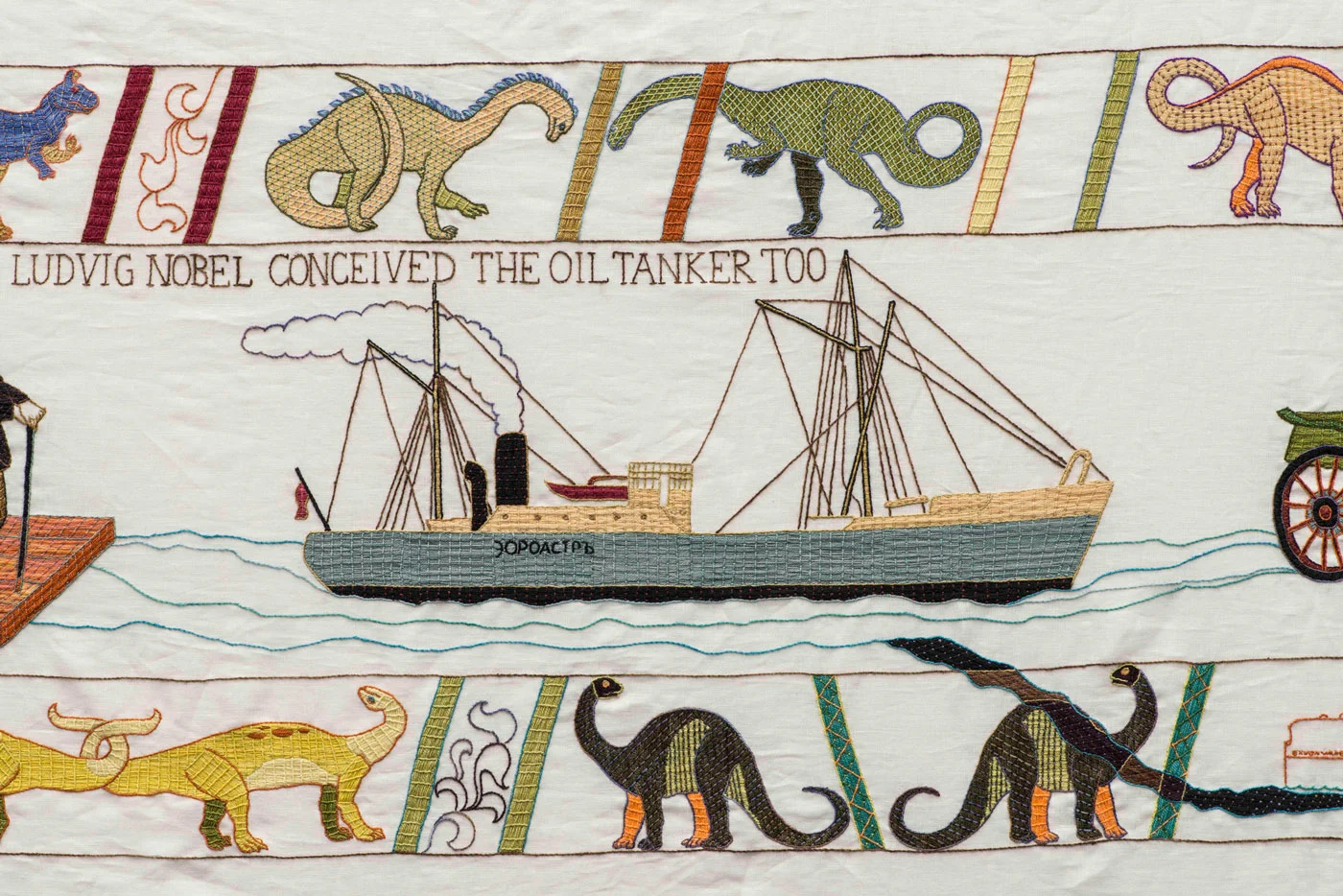

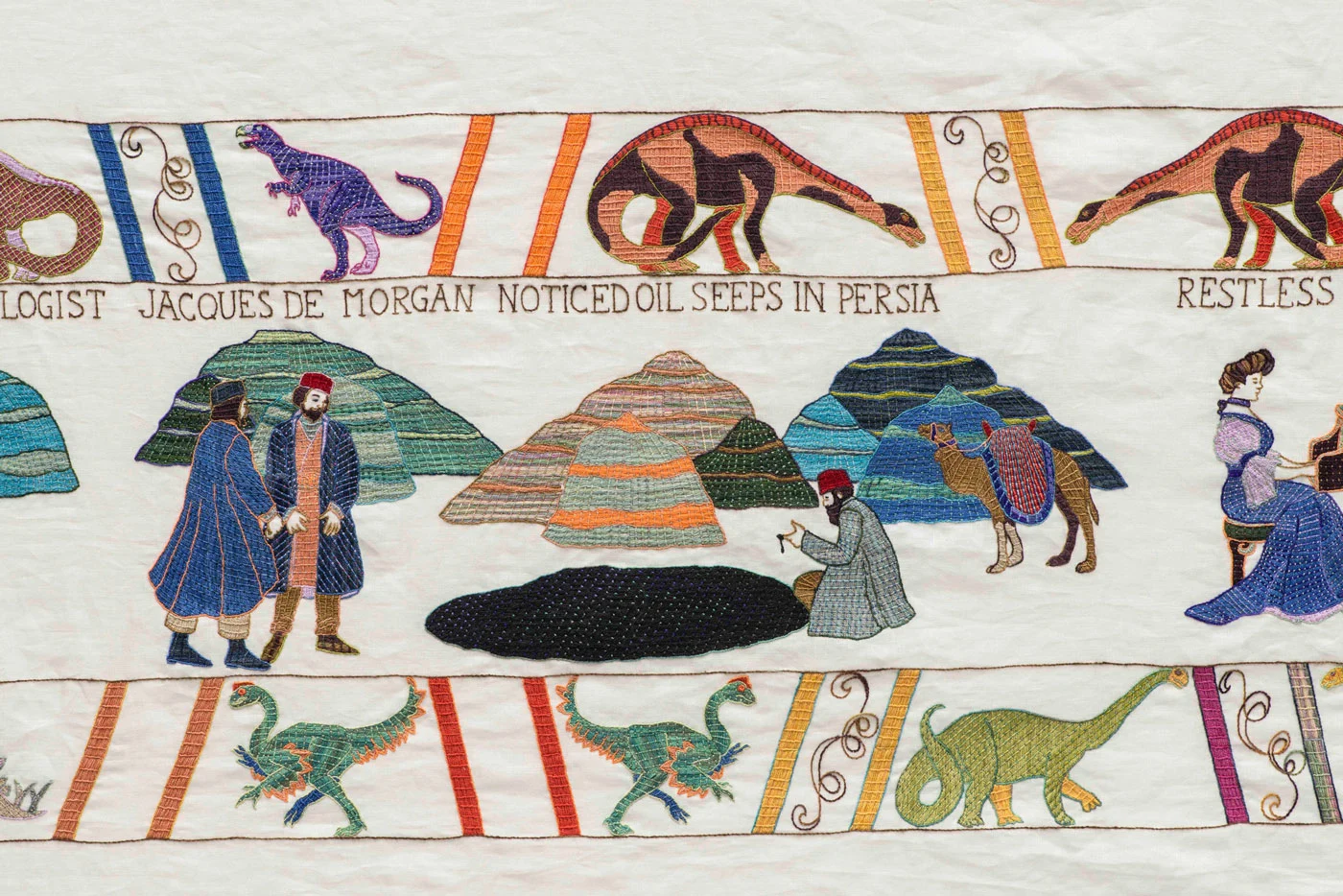

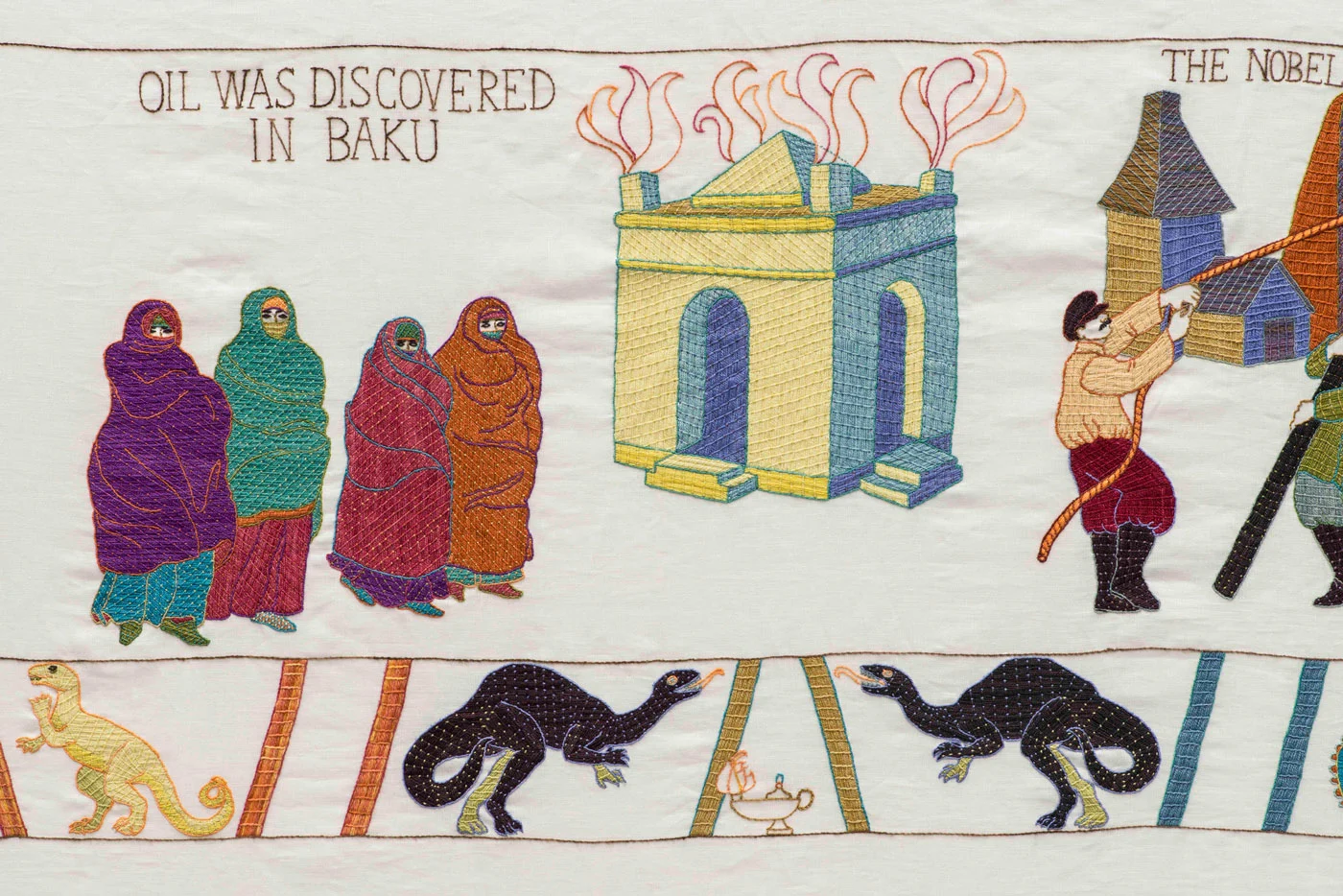

The Black Gold Tapestry is a huge, hand-stitched tapestry, which, in chronological order, depicts a monumental visual history of what oil is, where it came from and how it changed the world. It’s packed with sharp and vibrant vignettes of centuries past, from the reed and bitumen palaces of Mesopotamian marsh tribes to the political maneuverings of tycoons like William Knox D’Arcy, who triggered the extractions of oil from Persia by Western powers, and whose actions still echo in modern-day Middle Eastern conflicts. “It’s so interesting because a lot of the Earth sciences have grown up alongside the heavy industry of digging for coal and mining for oil,” says Sandra, “so a lot of our knowledge of the world has come from this same material we’re burning.”

I thought a project like this could change the way oil is being talked about.

It was after attending an embroidery exhibition in her hometown of Calgary, Alberta, that Sandra decided to draft ideas for the tapestry. “I thought about the Bayeux Tapestry,” she says, referring to the famous 11th century artwork which tells the story of the Norman Conquest of England. “It’s like an early animated film. It’s storytelling. I thought, why don’t I try to do an epic film on cloth using this method?”

I thought a project like this could change the way oil is being talked about.

For a decade, she worked 65-hour weeks in a small room at home creating what would become a colossal tapestry that stretched to 220 feet when it was finally exhibited at the Glenbow Museum in 2017. Years of research and drawing turned into many more years of hand-stitching. “I’ve been interested in environmental matters since the 70s,” says Sandra. “I thought a project like this could change the way oil is being talked about. I wanted people to understand the human side of this story.”

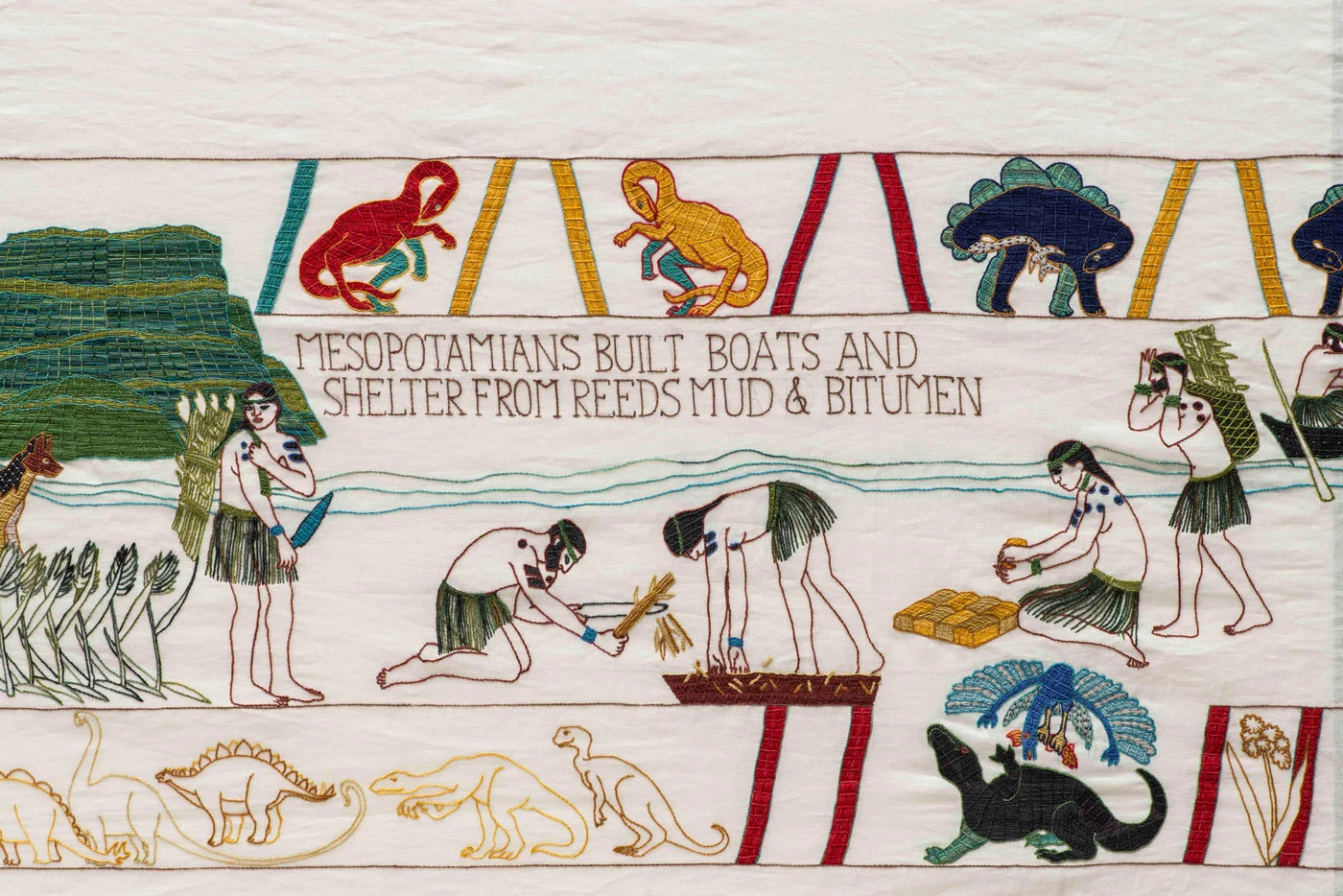

Mesopotamians use bitumen

“I was looking for a starting point and was led to Mesopotamia. The Marsh Arabs were using reeds, mud, and bitumen (a sticky black form of petroleum) because bitumen was bubbling up in the river areas there. They used simple materials to make a very rich and cultural life. When I was trying to find out what clothing they were wearing, there wasn’t much to go on. There are also these little clay figurines from the Ubaid period in the British Museum. The head shapes looked alien and the body shapes were different to what we know, and they had these interesting markings on their bodies which could have been made using the bitumen. I just loved trying to figure out what their tactile, material everyday life was like, rather than just their wars and great kings.”

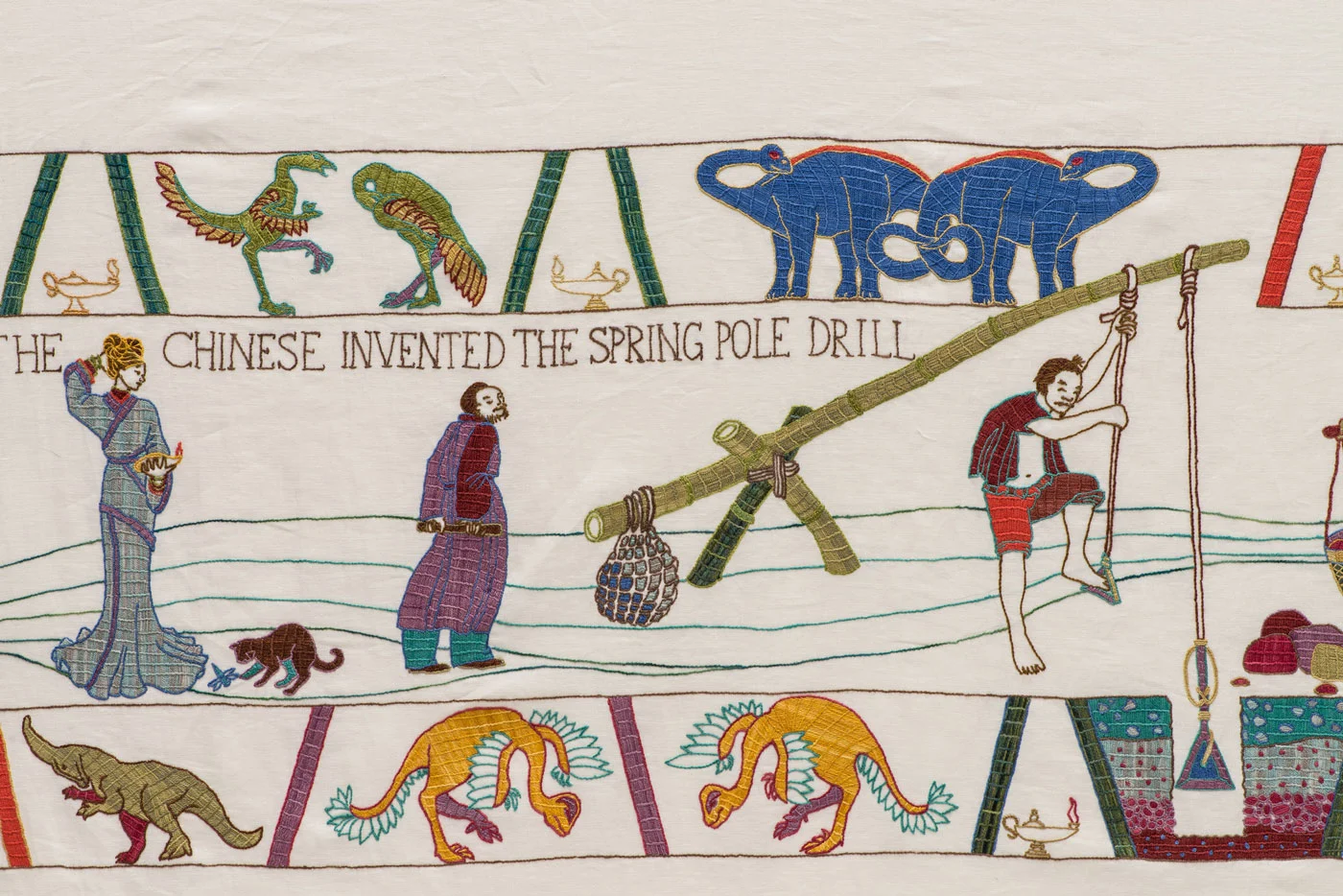

Evaporating brine

“More than 2000 years ago, the Chinese invented drilling technology and they were using it to get to salt brine. In the process of drilling for brine they would sometimes hit pockets of gas, which were invisible and would either kill them or explode. They became terrified of it, but over time started to realize that it could be harnessed. They managed to trap the gas and pipe it, using bamboo, to these stoves where they could heat up the water that contained the brine and evaporate it faster. By around 200 BC, they were already cooking salt brine with gas, using pipelines made from bamboo. And of course salt was one of the things that opened up the Silk Road trading route. What I loved about this story was going around the world and seeing so many stories of ingenuity that have been forgotten.”

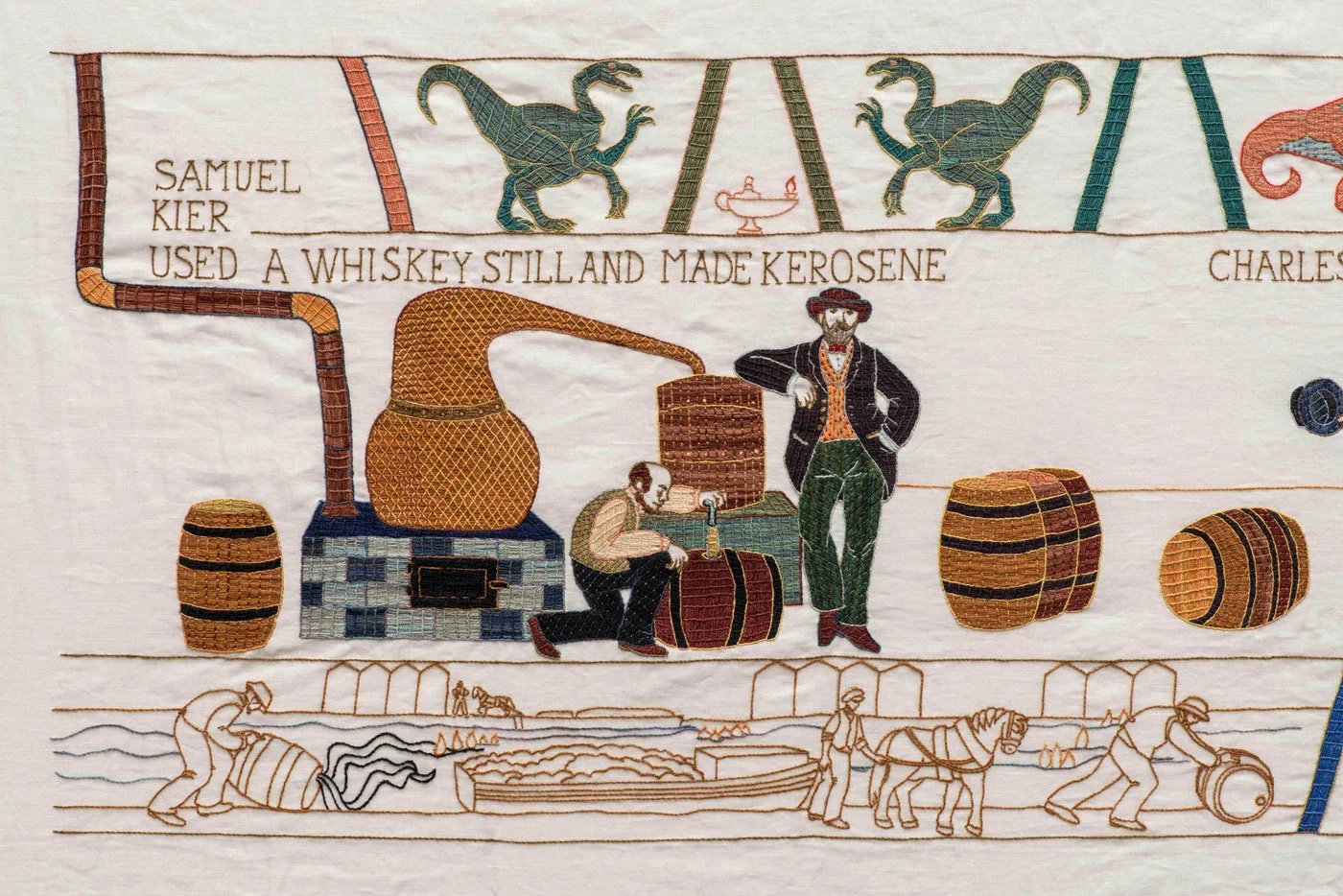

Samuel Kier

“In America in the 1800s, Samuel Kier was also drilling for salt brine, and when you’re drilling for salt brine you sometimes get oil. At the time there was no real business for petroleum oil and it was useless for Samuel’s salt wells. At night, Samuel would get rid of it by throwing it into the river. It would pollute the water, and sometimes catch fire, angering the townspeople downstream. That it caught fire gave Samuel an idea; he’d heard people were making kerosene from coal oil, so he tried making kerosene with his petroleum oil. He had to refine it first, though. So he borrowed a cast-iron still, and started to distill it into kerosene. An acquaintance of his, Charles Lockhart, brought some of it to England, because it was so much easier to get petroleum oil out of the ground than coal. The oil boom came soon after that. Samuel didn’t benefit from the oil boom at all, but Charles did. He became one of the early partners in Standard Oil Co, which was established in 1870 in America. I just loved that all this happened because some people were upset about him polluting the river.”

Bertha Benz

“This is the story of Bertha Benz. She was a young woman when she married her husband Karl Benz. She gave him her dowry, supporting him in his endeavor to build a horseless carriage – a vehicle that had a combustion engine. From what we can gather, he always felt that something wasn’t quite right with the engine prototype, despite having worked on it for years. One morning Bertha and her teenage sons decided to push the vehicle out onto the road, and she drove it 56 miles to her mother’s house and telegraphed her husband from there. Up until that moment, it had only been driven up and down the street. Nobody had ever gone that far on any motorized vehicle before. By taking the car for a test drive, she was able to identify what needed to be improved, such as the need for a brake lining and a lower gear. That first journey with the Benz Patent-Motorwagon led to the creation of what would later become modern-day Mercedes-Benz. She wanted to prove to him it didn’t need to be perfect, it just needed to get out there. It was good enough.”

Quadricycle

“This is around the time of the Paris Exposition in 1900. It was where William Knox D’Arcy first met Antoine Kitabchi Khan, a high-ranking Iranian officer, and he became involved in the extraction of Persian oil. On the left you see Henry Ford with his quadricycle, which was basically just a cart with bicycle wheels and an internal combustion engine. Thomas Edison was also there with his new movie camera, and they had moving sidewalks, like escalators but going around the exposition. The Eiffel Tower was still yellow, one of its early colors. Just a little further down the tapestry there is Rudolf Diesel, who invented the ‘diesel engine’ to run on peanut oil, because he felt oil could possibly run out, so we should have an alternative option. He disappeared from a boat a few years later, and there’s quite a bit of conjecture as to how he died. I just liked the fact that so many things happened at that exposition.”