On a trip to a local market, Egyptian artist Sakran noticed that authentic galabayas (traditional Egyptian garments worn by both men and women), were hard to come by. Some of the ones on offer were covered with tacky logos copied from Western brands. She responded with a research paper, A stand against deculturation, which was then turned into a photography series by Zeinab El Tawil. Here, the two chat to writer Alya Mooro about their hope that Egyptians can work together and realize the power in their own, authentic heritage.

When she initially started her research, the questions Sakran, born Hana Saleh, wanted answered were: where had all the traditional galabayas gone, what had caused the traditional Egyptian aesthetic to undergo such “deculturation” and what was up with all the kitsch? In getting those answers, she ended up tapping into a conversation about social class, globalization and the importance of individuality in Egypt.

Deculturation, as she explains in her paper, is when aspects of one culture are lost after contact with another. Originally due to colonialism, she writes, it is globalization that now serves to deculture and decontextualize. It’s why we now have a shared global culture, one which is definitively American. A global culture that means that even in local Cairo markets, traditional galabayas have been made kitsch.

Kitsch, as German philosopher Thorsten Botz-Bornstein put it, is “a tasteless copy of an existing style or the systematic display of bad taste/artistic deficiency.” But it’s not anymore, posits Sakran.

Over a Zoom call, she explains how she had initially wanted to understand why there was so much kitsch in Egypt, and soon came to realise that globalization had a big role to play in its pervasiveness, as did the lower class.

“That led me to look up papers about globalization…I ended up looking at the latest trends and shoots and found that they look quite similar to the things that are seen as kitsch here,” she explains. “I was able to make that link at the very end: That the outside world loves kitsch designs but it’s still seen as something belonging to the lower class, and that that’s something that we shouldn’t do.”

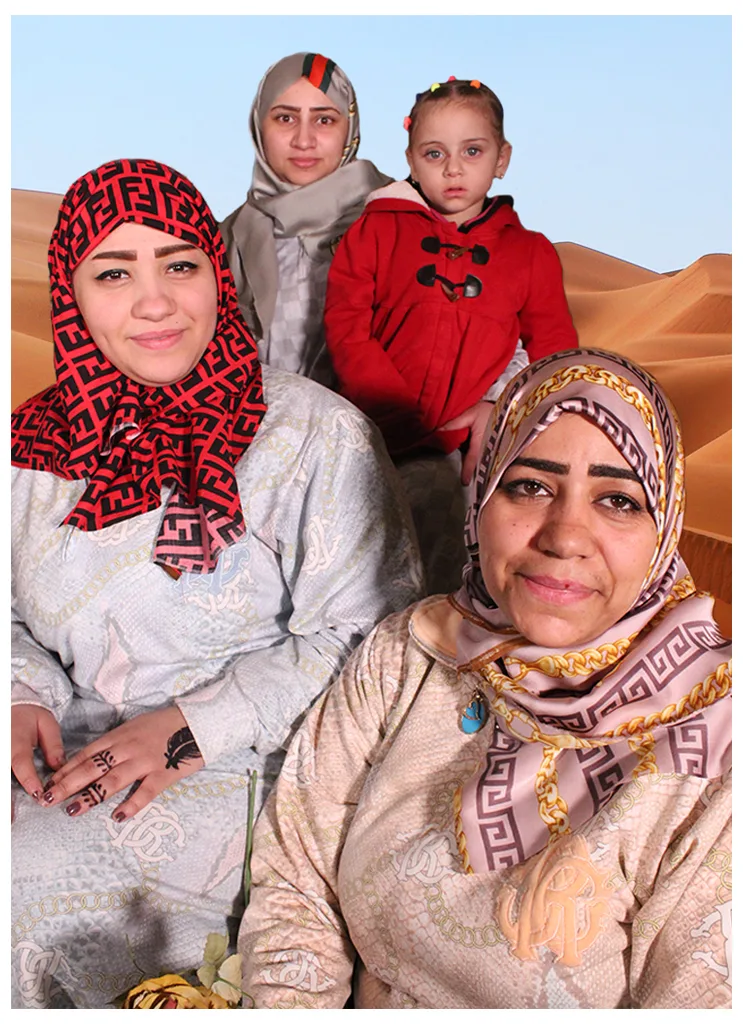

It’s this the duo leant into for the photography series, setting Egyptian women against the backdrop of a desert dressed in kitschy galabayas and surrounded by kitschy props; everything from imitation Dolce & Gabbana caps to the “Saudi slippers” that have Armani logos on them.

Because we’re now living in an age of hyperbole and exaggeration, Hana suggests, kitsch has become the global aesthetic – and a beautiful one at that. She goes on to cite several recent kitschy examples from pop culture, including a shoot for Rihanna’s SavagexFenty collection, which sees the artist surrounded by red teddy bears and hearts.

In the West they’re able to [create authentically] because there’s more individuality.

Those same items are everywhere in Cairo, she argues, but instead of being revered like their Western counterparts, local renditions are considered bee2a, a colloquial Arabic expression which means “tacky” and “lower class.”

As Hana outlines in her paper, Egypt has an extremely large population, more than half of which are lower class, as well as an entrenched social hierarchy. With the lower classes unable to afford the expensive Western labels the rich buy, in an effort to obtain cultural capital, they create their own inspired kitschy designs. This means that Egypt is filled with kitsch “like no other country,” but also that those designs are not looked at favorably.

The pair, who first met in school, have always wanted to work together and Zeinab was actually with Hana when searching for the galabayas. Once the research was compiled, the shoot came together collaboratively and spontaneously. A trip to a local market provided them with pretty much everything they needed. A logo-laden oriental carpet was borrowed from the home of Hana’s boyfriend’s parents, and a set-up was staged in her villa.

Casting for the shoot was initially challenging, they tell me, as photographing women of a specific class was imperative to the project. Hana ended up asking her maid to help them.

While she was quickly obliged (and presented with 10 women instead of the requested six), it was a challenge for the women to take a day off from work and find someone to look after their children. The women did not initially understand why the duo would even want to take pictures of them.

But they were naturals in front of the camera, says Zeinab, and made the pictures stand alive. “Usually when I’m shooting I really have to work for it but this time it was so natural,” she tells me. “In the end they did everything, I just had to click.” Many of the women have called Hana since, asking to be considered for future shoots, amazed that instead of their usual day jobs they can “get paid to take pictures and eat pizza.”

I ended up looking at the latest trends and shoots [in the West] and found that they look quite similar to the things that are seen as kitsch here.

Their collaboration is, they hope, an example of what can be accomplished when something is done authentically. The importance of that is something they returned to often during our conversation, and something they argue is greatly lacking in Egyptian culture.

“In the West they’re able to because there's more individuality,” Hana tells me. “When it comes to , other than classes, it always has to do with being in a group… There's always some kind of judgment made… so people are always restricted and don't do their own thing.”

Much of Cairo’s authentic kitsch nature and expression is therefore played down, she argues. Because things are not created authentically and with individuality, they then don’t have as much of an impact, she explains. It’s this, in part, which is preventing Egypt’s ascent to the global stage.

In her paper, Hana cites success stories like Liverpool player Mohamed Salah and Shaabi music, (a form of electro created by Egypt’s lower class which has been garnering attention internationally), as examples of the reach and impact possible when authentic.

“We should help each other see our potential and what we could do,” she tells me. “The lower classes could produce so many beautiful kitsch things that would be loved . They only need someone who's well off who's able to travel and …

“ there's no confidence in anyone's designs if it's not western,” she continues. “Even if someone from the lower classes has a very nice design and goes to someone from the upper class , would be kind of embarrassed to show that to anyone.”

If Egyptians of all classes were able to recognise the cultural richness and authenticity in the designs made in their own country and begin working together, it would help dissolve socioeconomic barriers, Hana suggests. It would also raise the potential for an artistic community, provide resistance against deculturation and allow Egypt to have a global influence. It is, she alleges, the only way there will ever be an Arab Kanye West or Anna Wintour.

We should help each other see our potential and what we could do.

Both believe the tide is turning however, in part due to the waning American star. But, as Hana explains, it’s also thanks to a concerted effort by the Egyptian government who have, since the 2011 revolution, been trying to foster an entrepreneurial mindset in the country.

“There are more R&B and rap songs, there is more entertainment; on TikTok and YouTube people are watching stuff that is more domestically created,” she tells me. “I honestly don't really know what's going on in the States because I just don't really watch any US channels anymore.”

In truth, it’s becoming increasingly easier to see – and thus be – yourself, as an Arab. Perhaps, then, the time is soon approaching for the Arab world’s very own kitschy Kanye West. There are arguably already a few contenders.