The Royal Academy of Arts has held the Summer Exhibition for 252 years, without once missing a year. Even during the First and Second World Wars, they kept calm and carried on. This year was no different in that respect: they have not been stopped by Covid-19, or by the fact that the summer has passed most of us by. Writer and podcaster Ferren Gipson speaks to the curators behind one of the most extraordinary years the exhibition has clung on through.

The selection process began in January as it always does, but as February and March rolled on, it became increasingly clear to the team that they would need to make adjustments for the annual show as institutions around the world were forced to close their doors. And so, it has come to pass that the Summer Exhibition 2020 will have the asterisk of having taken place over the autumn and winter, but it’s a sort of badass asterisk to bear, considering the incredible challenges the year has brought.

The Exhibition

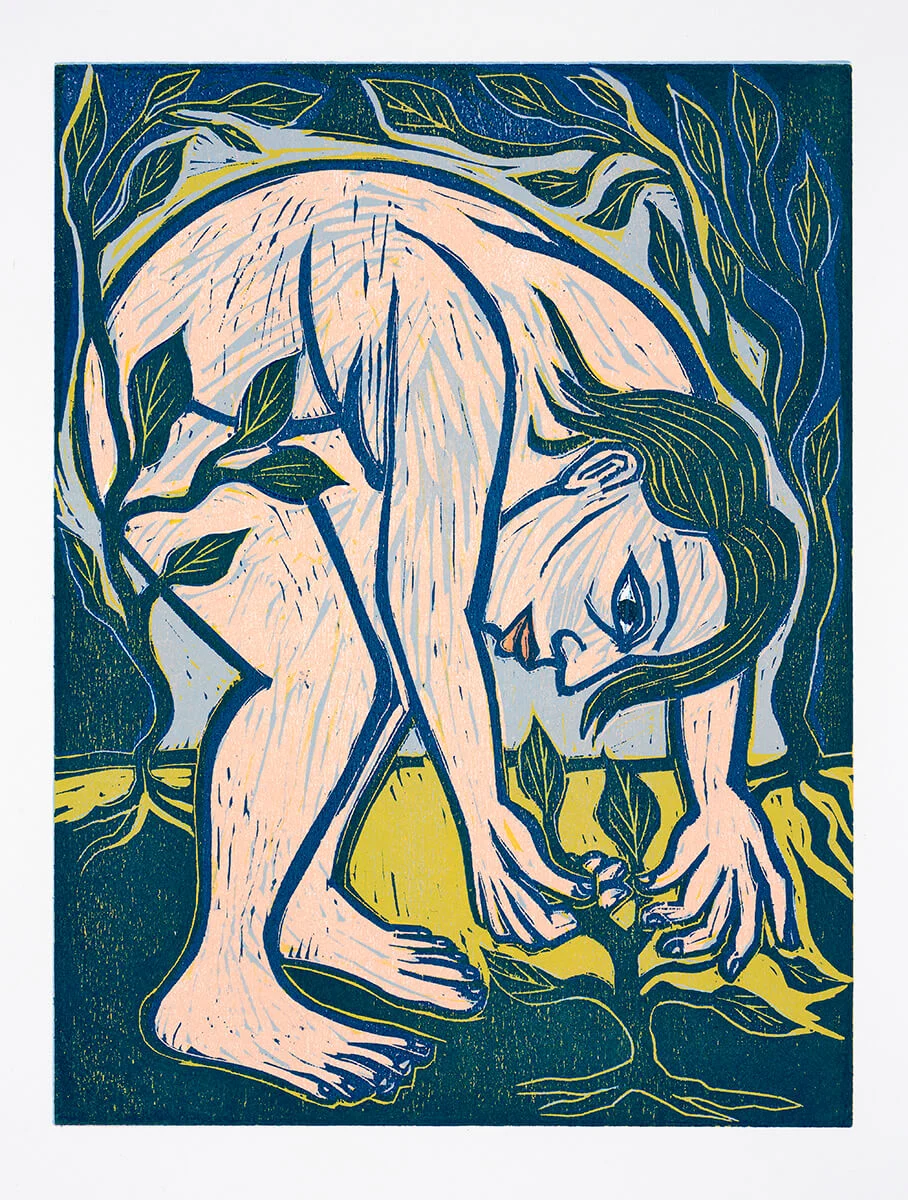

The Summer Exhibition is difficult to define. The beauty of it is that it holds different meanings depending on how you are experiencing it. For artists around the world, it is an opportunity to submit work for display in a prestigious institution. Emerging and lesser-known artists can see their work hanging alongside the works of some of the most celebrated artists working today. This year’s show includes new works by Ai Weiwei, Chris Ofili, Gillian Wearing and more. For the Royal Academy, it is a crucial opportunity to raise money to support the Royal Academy Schools: a free post-graduate course offered to a small group of artists each year. The course’s alumni includes illustrious names like J. M. W. Turner, William Blake and, more recently, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye and Michael Armitage. The teaching staff are some of the best in the world. Tracey Emin served as Eranda Professor of Drawing from 2011 to 2013, and conceptual artist Michael Landy held the same position between 2014 and 2016. Finally, gallery-goers have a chance to view and buy any of the works on display. This may sound like a potentially expensive endeavour to a budding art collector, but there are actually a number of very affordably priced works on show, particularly the editioned prints.

“An editioned work is a really amazing opportunity to buy something special,” says committee member Eileen Cooper RA, who curated the print rooms. “I love the whole ethos of print and the feel of print. I love the integrated surface you get with print that you don't get with a painting. I'm encouraging people to buy, and I hope they buy online.”

Before the exhibition, there was nowhere for contemporary artists to share their work to the public, because everything was commissioned and went straight into collections.

The Judging Process

This year’s exhibition includes over 1,000 works. The selection and hanging committee are headed by Jane and Louise Wilson RA , twin sisters working in the mediums of photography and film. They were among the first members to be elected as a duo. The remaining committee members include Sonia Boyce RA, Eileen Cooper RA, Stephen Farthing RA, Isaac Julien RA and David Remfry RA.

Let’s do quick introductions… Sonia Boyce is serving as a committee member for the first time and brought her collaborative spirit to encourage different and more diverse voices to submit work to this year’s show. After serving as Head of Printmaking at the RA Schools for five years, committee member Eileen Cooper was the first woman to be elected Keeper of the Royal Academy, which is the artist charged with overseeing the Schools. David Remfry states that he selected works that he felt had an element of joy, and his room is filled with a stunning selection of portraiture. Turner prize-nominated artist Isaac Julien has taken a completely unique and personal approach to his room by curating a tribute to his friend and colleague, Okwui Enwezor (more on this later). Architect and designer Eva Jiřičná brought her modern point-of-view to curate the architecture room celebrating the technical and conceptual aspects of the field. Stephen Farthing, who has also taught at the school, curated the largest room. He drew on his well-documented love of color to guide his approach. Finally, Turner Prize winner Richard Deacon has curated the sculpture room. It’s an eclectic team, which is reflected in the different approaches to each room and the inclusive spirit of this year’s exhibition.

We’re trying to challenge hierarchies. It wasn’t to be negative, it was something to embrace and feel positive about.

There were more than 18,000 entries submitted for blind selection this year. That initial list was narrowed down to a list of around 2,000. The process is a brilliant equalizer, where each artist is considered purely on the merit of their work. The committee assesses digital images to see if they want to see more of the work in person without any information about the entrant. The first stage is a kind of art version of Tinder: Left. Right. Left. After the list was narrowed considerably, the 2,000 works were viewed in person and narrowed further to the 1,172 pieces on display. Royal Academicians – people elected to become members of the Royal Academy by fellow member artists – also submit works for display each year. These works mingle with each other in the hallowed galleries of the RA, creating interesting groupings that you would never see anywhere else.

The importance of Color

Each committee member is responsible for a section of the exhibition, bringing a personal perspective to the way they have hung their galleries. Stephen Farthing RA curated the largest gallery, which is one of the few rooms to predominately feature work from Royal Academicians and Honorary Academicians. Because these works are selected in a slightly different way to the public submissions, Stephen was not able to take a thematic approach to curate which pieces went in the room. Instead, he chose to experiment with hanging works based on their color. He explained that he has a fascination with how artists use different hues and tones in their work. In fact, in 2018, Stephen and Yale University professor David Kastan wrote the book On Color, exploring its applications and effects in our everyday lives.

I’m interested in how color has come to play an enormous role in the lives of artists who lived in London.

As visitors enter the room, they are greeted with a burst of color on their immediate left. The graphic hues of Michael Craig-Martin sit alongside the vibrant works of Mimmo Paladino and Stephen’s own work. The paintings on two long walls of the gallery move from brighter to more subtle shades, as though the saturation from the walls as the viewer moves down the room. It is a visually pleasing approach that removes each work from any thematic groupings. You can think of it as arranging a library by the color of the books – suddenly you need to engage with each cover or painting to really connect with the message.

“I felt it might be possible to tell a story as the person walked,” says Stephen. “That there was this sense of it not just being lots of paintings, but paintings that were put next to each other, not for some kind of aesthetic reason or because I was trying to get all the dog paintings into one section and all the cat paintings into another. So not treating it a little bit the way a zookeeper does, but actually to try and create an interesting experience for the viewer.”

This idea of contrasting tones is beautifully embodied in three pieces by Rebecca Salter PRA in gallery three. The trio is hung across a corner, with the two brighter paintings on the colorful wall and the third, comparatively monochromatic painting on the perpendicular wall alongside other less saturated works. They are still hung together, but by having one piece turn a corner, it feels like it playfully bucks some unsaid rule about how to hang paintings. It is a clever way to accentuate the hanging concept.

A diptych by Stephen Farthing titled STUDY FOR A PORTRAIT OF A FAT CAT IN THE AGE OF THE OLIGARCHY and STUDY FOR A PORTRAIT OF AN OLIGARCH IN THE AGE OF PLUTOCRACY are hung in a grid of four images – two with bright hues and bold orange and black tiger stripes, and two with desaturated greys and muted tones. Within this set, you can see Farthing’s curiosity with color and his willingness to challenge himself with his use – or disuse – of color.

Gallery three is the only room hung in this way, but once the idea of color play is introduced, you begin to think about objects and rooms across the exhibition differently. Suddenly, you may notice the brightness of the print rooms compared to the starkness of the architecture room. Or perhaps you are drawn to David Batchelor’s two Inter-Concreto sculptures . They are siblings in style, but one is a blossom of color and the other fans out in more neutral hues.

An exhibition concept of this style is made more feasible, in part, because of the controlled route visitors will take through the gallery this year. Due to Covid-19, it is necessary for small groups to enter from one gallery and move in a fixed one-way path through the exhibition. Stephen Farthing equates this to an experience like turning pages in a book, which is useful if you want to shape the experience visitors have as they move through a space.

A Wealth of Human Stories

The largest overarching theme across the exhibition seems to focus on sharing human stories. This reveals itself in a large number of portraits – particularly in the room curated by David Remfry RA – and in the stories behind various other works. David comments on how interesting it is for the selection committee not to know anything about the artists when they review public submissions. Works are assessed purely on their merit and no names or artist information is given. By working in this way, one begins to notice their assumptions and biases. He gives the example of a piece titled Unsung Heroes #2 (The Teacher) , which depicts a knitted portrait of a woman. Knitting is stereotypically considered to be a feminine art form and many people’s instinct may be to think the artist is a woman. The piece is actually by Rod Melvin, a male artist who is a dab hand at knitting. The subject of the portrait – a heroic teacher – is poignant considering recent sacrifices made by teachers and other key workers in carrying on with their duties throughout lockdown. Interestingly, it turns out that David Remfry had selected this work before the outbreak of Covid-19.

One of my heroes is Nina Simone. She said: An artist’s duty, as far as I'm concerned, is to reflect the times.

Continuing on the theme of textiles, a different sort of human story is told through an embroidered image by Conrad Atkinson titled Vincent’s Ear Uncovered and Euphonious Wound from the Metropolitan Museum New York. In a Pop Art-like fashion, Conrad repeats a stylised image of Van Gogh’s famously sliced earlobe in a grid across the canvas. The red of the blood is embroidered in a painterly splash and the gold of his ear twists elegantly in a harp-like shape. Without knowing the subject, you could think it was a purely abstract image. But the subject of Van Gogh instantly summons dark thoughts of a tortured artist and the personal challenges the artist faced. Playfully, the word “euphonious” in the title means “pleasing to the ear.” It is a fitting pun for the way Conrad Atkinson’s portrayal of the ear manages to be visually pleasing despite the gore and tragedy of the story.

“I think it's a really powerful work because it doesn't speak about the primacy of oil on canvas at all. It probably speaks a bit more about a domestic act of embroidering. And I think there's something quite powerful about that as a political statement, especially in relation to showing his wife, Margaret Harrison as well,” says Louise Wilson. “I know they share a studio, both Conrad and Margaret share a studio, and have a great support for each other and recognition of one another's work. And I think it's a really, just a really powerful message to see a duo who are working so extraordinarily ahead of their field and have done for several decades and are producing such exceptional work continuously.”

Across the room from Conrad Atkinson’s work is a large piece by feminist artist Margaret Harrison titled Pain, Pleasure & Power . The mixed media image is a tangle of jungle plants and collaged images that represent the ideas within the title. Amongst the many images, we see a huge building as a form of power, a framed image of Syrian men gathered around a body as an image of pain, and a photograph of a bride for… pleasure? Power? The bride stands out in contrast to the other images as one that is considered by many to be a happy occasion. For some brides, marriage may represent a loss of power. The viewer must consider what it represents within the context of the patriarchal forces at play in the wider collage.

The stories behind works and artists are one of the greatest joys of art. Art should connect us to each other and to ourselves. It should draw out the humanity in the beautiful and the difficult. Though this article will carry on to explore two further themes, they are each underpinned by this idea of human experiences.

Art should connect us to each other and to ourselves. It should draw out the humanity in the beautiful and the difficult.

The Importance of Different Perspectives

Each committee member has been guided by their passions, and we see a diversity of perspectives across themes, artists and styles. Sonia Boyce RA and Isaac Julien RA have also undoubtedly tapped into a more diverse pool of artists, which is an encouraging move for an exhibition of this scale. Isaac, in particular, pulls together an all-star room of artists from the African Diaspora to pay homage to renowned curator Okwui Enwezor, who passed away in 2019. Julien’s selections celebrate the life and impact of Enwezor through artists he loved and who loved him in return. It speaks to Okwui’s widely held esteem that every artist Julien asked to take part in the room agreed to show a piece.

Okwui Enwezor was a curator, educator, critic and champion of a global art perspective. In his early career he did not accept that there was no space for artists from the African Diaspora within the art world. He challenged the conventions again and again. In 1996, he curated an exhibition on African photography at the Guggenheim in New York. In 2015, he curated the main exhibition for the Venice Biennale. He was a force, putting his weight behind the careers of Steve McQueen, Shirin Neshat, and more. Moving through Isaac Julien’s rooms in the exhibition, one gets the sense of the breadth and impact of Okwui’s reach.

He was a person who single-handedly changed the art world to how we think of it today.

Isaac Julien’s rooms are the entry point for the exhibition. It is a powerhouse of a section, featuring works from 2019 Turner Prize winner Oscar Murillo, committee member Sonia Boyce, Royal Academician Frank Bowling and more. True to form, Frank’s painting is a vibrant wash of vivid color. A line of blue drips down the canvas, bleeding into pinks and yellows. It is this expressive work that garnered Bowling so much well-deserved acclaim. In 2017, Okwui Enwezor curated a retrospective of Frank Bowling’s work at Haus Der Kunst in Germany titled Mappa Mundi and wrote the accompanying exhibition catalog. Okwui pushed for showcasing diverse perspectives on a global scale, and Isaac Julien has thoughtfully brought this energy to this year’s exhibition.

In a literal sense of the theme of sharing different perspectives, Turner Prize winner Grayson Perry’s work The American Dream represents many viewpoints within the current US political climate. The red and blue print shows a map of the United States under attack. War planes fly overhead with labels like “climate change” and “intersectionality.” On the ground, cities have similar labels, such as “allies” or abstract things like “craft beer.” Red rays emanate from Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg’s quizzical face and bear messages such as “fear” and “alienated.” Grayson captures the fraught socio-political state of the United States as people struggle to wade through truth, lies and political motivations. His visualization of this would nearly be comical if the reality of the situation was not so desperately concerning.

The piece is a wall hanging, but essentially it is a rug sack. It’s a functional item. To me it’s very architectural.

In the architecture room, Eva Jiřičná chose to display a soft sculpture by Michael Lisle-Taylor titled Sabrina . Hanging on the wall, we see strapped components in neat compartments. The items inside expand to make a large inflatable swan with a tent-like cover. It is an unexpected addition to the architecture room, in some ways, but Eva selected it because of the architectural nature of designing such a small space. It is a whimsical take on the architectural remit of the room but is no less valid than any other perspective.

“I think if we were to just look at the different people involved in the committee, the exhibition hopefully reflects all of that diversity and all of that difference in age and perspectives,” says Jane Wilson. “I think that's very important, that it has a very diverse set of voices.”

The RA vs The Global Pandemic

There is a final key theme in the exhibition that was inescapable: Covid-19. For many, life right now feels like it is divided in pre- and post-Covid periods. Concerns around the virus have fed into the exhibition in different ways. Artists had to drop off their works in booked slots. Visitors must explore in small groups, with a set entrance and exit. Some of the curators have had to work remotely, liaising with the hanging team via video calls.

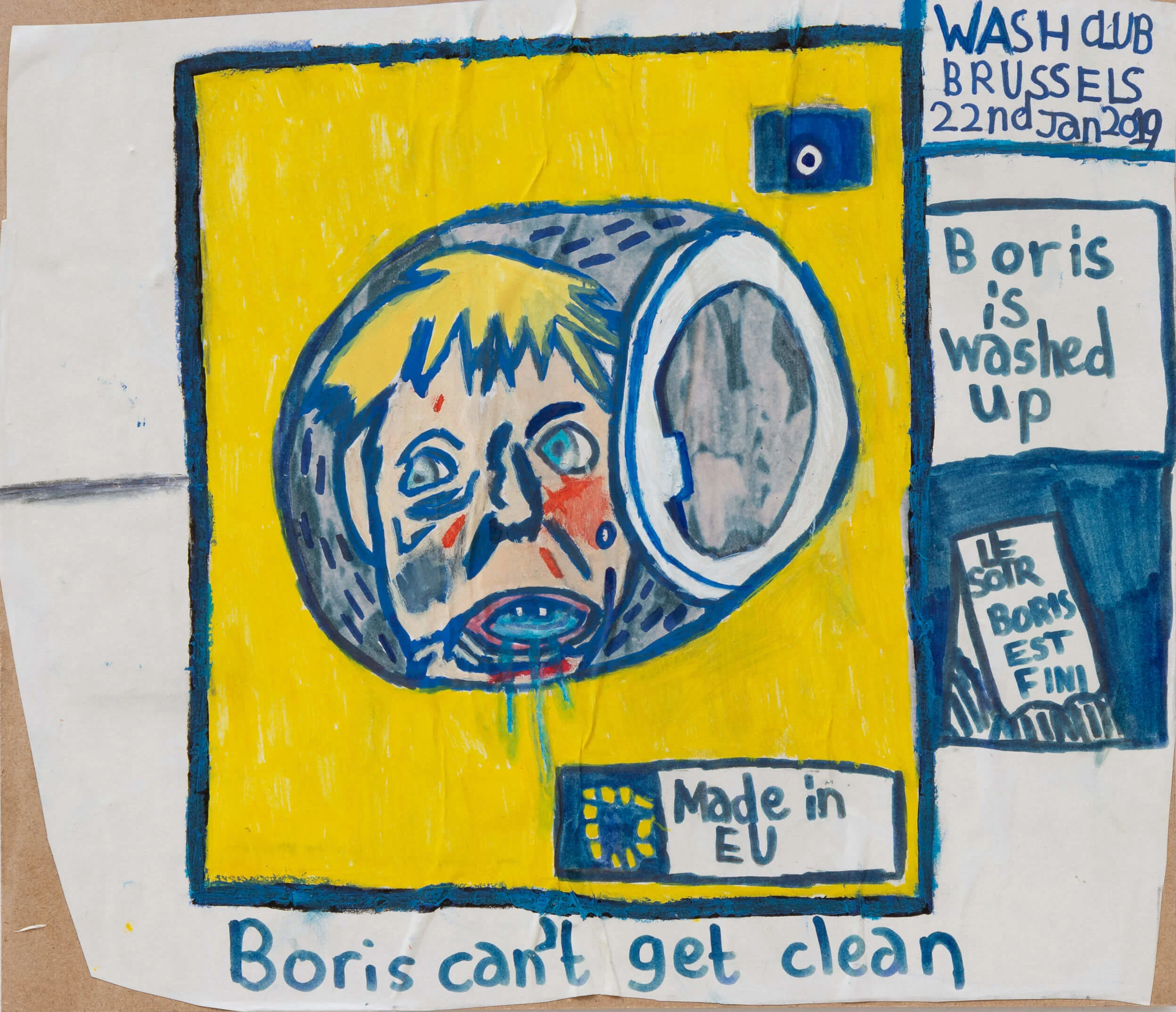

Most of the artworks for the Summer Exhibition were selected prior to the events of the pandemic, but there are some works selected later that address this subject head-on. In Sonia Boyce’s room, there is a video piece by John Smith titled Twice . It begins with Smith washing his hands while singing Happy Birthday twice, as we were all advised to do this summer. The twist is that he sings it to the tune of a funeral march. This clip is followed by a video of UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson during the early stages of the pandemic advising that most people can go about “business as usual” as long as we all wash our hands. We then understand the funeral march version of Happy Birthday to be a criticism of the folly of this advice and the lives lost due to a slow response to the pandemic.

In another video installation in Jane and Louise Wilson’s room, Korean collective Young Hai-Chang Heavy Industries present an unsettling piece titled C.D.C. WARNS OF AGGRESSIVE PEOPLE SEARCHING FOR FOOD DURING SHUTDOWNS . Jazz music plays in the background as words from a fictional story flash on the screen to the melody. The narrative tells of a situation where people have become desperate for food during a lockdown scenario. It does not recount actual events or mention Covid-19, but it is what you could call Covid-adjacent. The story seems just possible enough to make a viewer slightly uneasy.

In a way their work can seem quite pleasurable and delightful to look at, but of course the subject matter is a lot more complex than that.

In the same area of the exhibition, a new piece by Gillian Wearing RA titled Lockdown Portrait depicts a recent self-portrait of the artist. “Gillian's made a whole set of works around the idea of the mask and using the mask as a kind of device to use for disguise and as a performance,” says Jane Wilson. “Particularly now with the pandemic and with the crisis, she's actually amplified that. And instead of taking off a mask, she's taken off her face.”

In other cases, such as the earlier knitted portrait of a teacher by Rod Melvin, some works selected before the crisis have taken on new meaning. This parallels the realities for many people around the world. We are all reassessing aspects of our lives under the new circumstances Covid-19 has introduced. It is a comfort, in some ways, that events like the Summer Exhibition are able to continue. It is a hopeful indicator that life does go on, even if it works a little differently than before.

It is a hopeful indicator that life does go on, even if it works a little differently than before.

The Show Must Go On

The Summer Exhibition is so special in its premise because artists from anywhere in the world can submit, no matter what stage they are at in their careers. This is, perhaps, the greatest theme across the exhibition’s 252-year history. Inevitably, a potpourri of stories and styles are brought together, allowing visitors to explore and purchase works they may never have seen. This year’s selection embraces the diversity of the art world and is a hopeful example of what is possible in major shows. It is a credit to the RA team and to the selection committee that, in the face of many logistical challenges, this year’s show did – as the old expression says – go on.

This article is part of the collaboration between WeTransfer and the Royal Academy to bring their incredible annual exhibition to a larger audience. The Summer Exhibition is open from 6 October until 3 January 2021.