Kazakhstani designer Roxana Adilbekova founded the fashion label Roxwear in 2017. Here, she speaks to writer Anastasiia Fedorova about how the label captures the identity struggles that come with growing up in a post-Soviet cultural landscape, and picks out five pieces from her collections that help tell its story.

Located in Central Asia, Kazakhstan exists at the intersection of ancient traditions, Soviet heritage, and the new generation’s strive for modernity. Designer Roxana Adilbekova, who founded the fashion label Roxwear in 2017, has a radical vision for the future as the country emerges from its complex past.

Raised in a multicultural family, she’s always been interested in her heritage. Her grandmother, an art historian specializing in Central Asia and applied arts, was a major influence. “I experienced a lot of our culture and history through her stories,” the designer remembers. “I feel that our region has a lot to offer culturally, and I'd love to share it with people from elsewhere. I’ve always wanted to create something to tell this story; fabric just happened to be the canvas I was most comfortable with.”

The past, however, is not Roxwear’s main focus. It’s centered around Kazakhstan’s contemporary culture and the creativity of its youth. Much of the country’s new generation dreams of a “Central Asian-centric world,” and the brand’s use of historic craft technologies and traditional silhouettes brings that dream closer to reality.

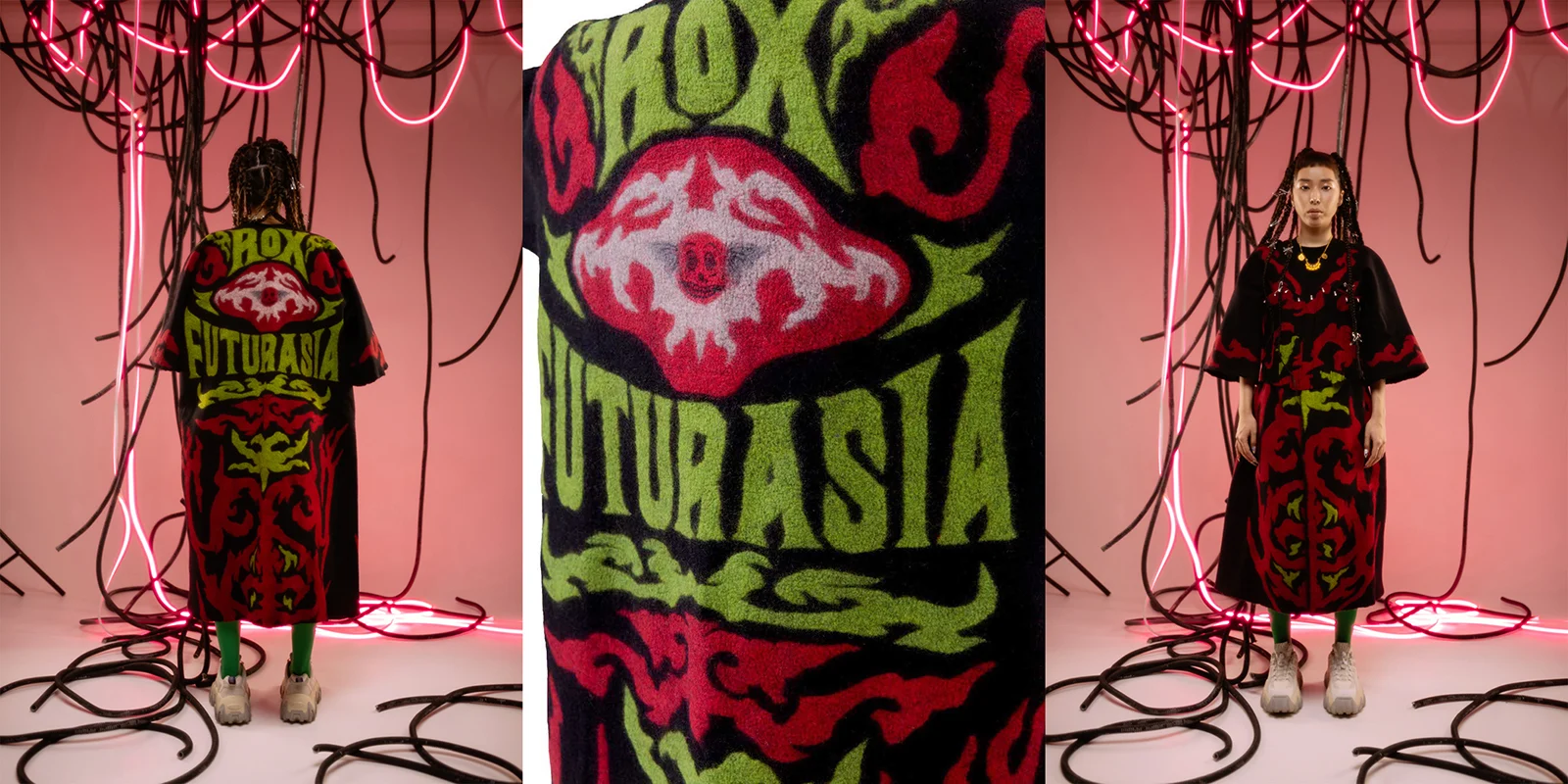

Roxwear’s SS21 collection Futurasia offers a Central Asian take on cyberpunk, as one more embodiment of this dream. This fictional world Roxana created for the collection is “filled with spaceships, androids and flying yurts, inspired by the best of what was available on VHS from behind the Iron Curtain.”

It’s interesting to see where our generation’s curiosity will take us.

The clash of nostalgia and aspiration, and the East and West, has been familiar to Roxana since her childhood. A former Soviet republic, Kazakhstan became independent in 1991, which ushered a turbulent decade of uncertainty – both economic and cultural.

“Our world was in tatters after the USSR fell apart, and then it was flooded with Western culture which started to dominate our own. People were lost, and couldn’t understand their own identity. But lately, I have a lot more hope. Our youth is becoming more creative and brave by the year, launching and developing new projects in various art industries. A lot of these projects seem to be putting us back in touch with our roots,” Roxana says.

The designer is convinced that Central Asian youth can contribute a truly unique vision to the global creative community. “Kazakh youth culture is constantly evolving,” Roxana says. “Our new generation is going through a major change, and it’s interesting to see where our curiosity will take us.”

PO-2 earring

PO-2 concrete fences were a permanent fixture in the urban landscape of Soviet and post-Soviet Kazakhstan. Roxana remembers that during her childhood grey solid blocks “were everywhere.” “I was born in Dushanbe during the civil war and grew up in the late ‘90s and early ‘00s in Kazakhstan. I don’t think that I’m the only one who noticed that the fences looked cool, but I wanted to capture that look and make it really polished. So, we turned them into earrings made of surgical steel. For me, these fences are a symbol of the USSR and the Iron Curtain; everything worth seeing was always behind them. Today, they’re still there, crumbling. It’s harrowing but beautiful.”

Chapan

This urban version of the traditional chapan coat was created for the Futurasia SS20 collection, which the designer describes as “simultaneously a lesson in history and a study of the future of the nomadic culture and lifestyle.”

“I imagined my ancestors if they lived in a futuristic, cyberpunk world. As far as I know, nobody has done letter felting on chapans before, so we pioneered this technique. Chapans are very durable and are passed down through generations, as they can survive for centuries. So who knows, maybe in a dystopian future, someone could still be wearing one,” she says.

Kopre T-shirts

The T-shirt, originally produced in a limited run of 50, was made using a patterned fabric which resembles kurak korpes, traditional quilted blankets. The shirts are actually a far cry from tradition, though. “The fabric might look similar to the traditional textiles, but it's actually made in China and has swans and roses on it, symbols that have nothing to do with Kazakh folk patterns. This design is a comment on the fact that we don’t know our history, but the irony was lost on most people. I’m still waiting for someone to ask me why there are roses on this garment. That’s why we added a note that says ‘Wearer discretion is advised’ on every piece.”

Pin-up Kazakh girls suit

The pink fabric for this outfit is printed with a custom pattern made up of cartoon pin-up girls in traditional Kazakh dress. Roxana wanted to challenge Uyat, a culture of shame which is oppressive and limiting for women. “Girls are told from a very young age that they can’t do things, and that they’re supposed to carry themselves in a certain way. There’s a lot of gaslighting and victim-blaming. This piece is a big ‘fuck you’ to all the oppressors. I had to switch print shops because some of them have refused to print this fabric, which I find pretty ironic,” she says.