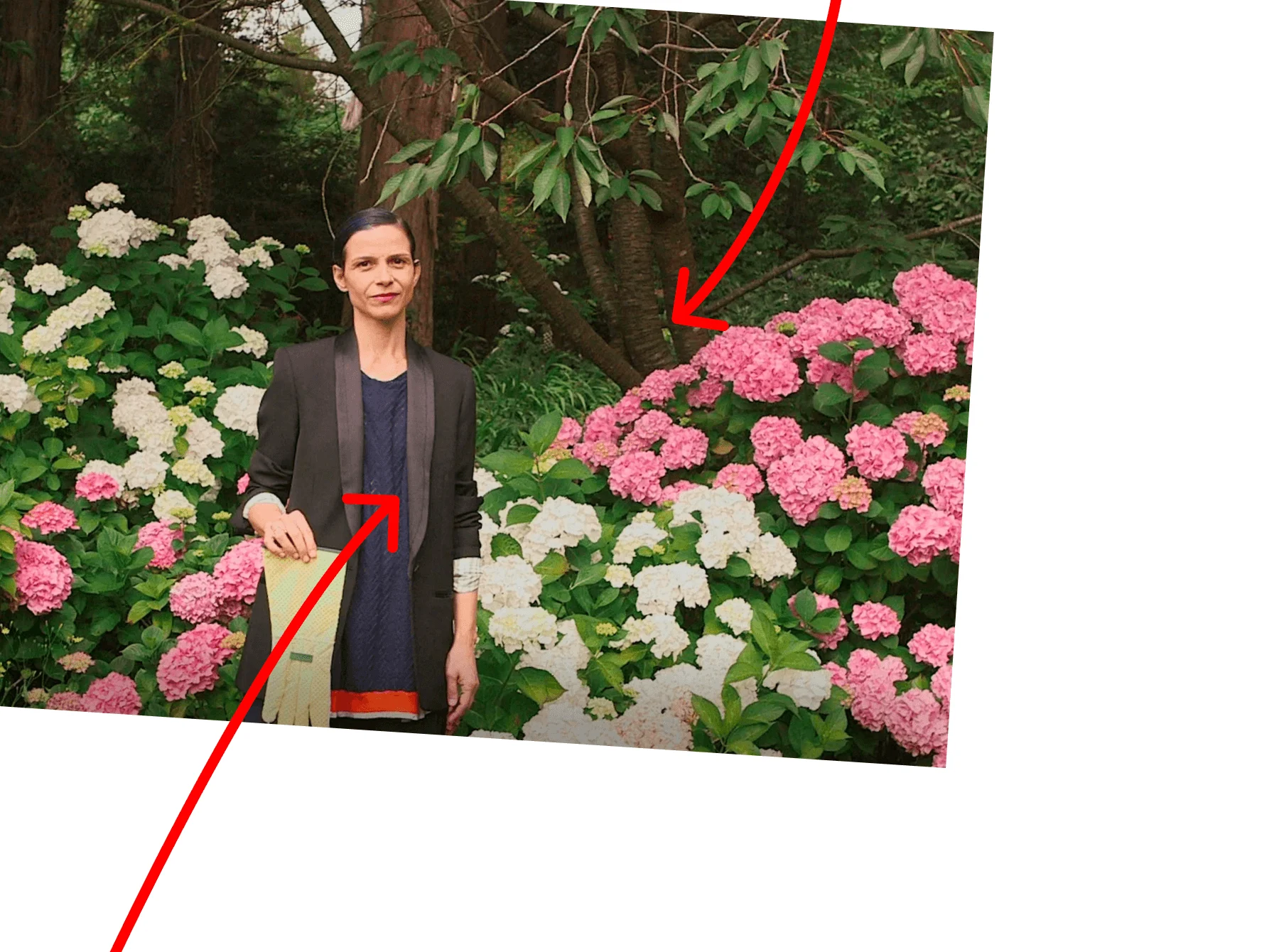

Galindo uses the limits of our body to confront social issues and inequality. Her works are heavy and emotionally charged, leaving us to question our bodies’ value in society.

Regina José Galindo uses her own body to explore issues of social injustice, violence and oppression, both in her native Guatemala and beyond. She has subjected herself to physical suffering, public indignation and even surgery to draw attention to these atrocities, using her vulnerability as a means to invoke empathy, and humanize a reality that has so often been ignored or erased from public consciousness.

Her first love was poetry

Born and raised in Guatemala City, Regina José Galindo had absolutely no artistic training. She enrolled in and dropped out of university several times, eventually gaining a degree in administrative assistance. She was, however, informed by her mother’s voracious appetite for reading, and it was the act of writing that first sparked her creativity. She kept a diary from the age of nine and began writing poetry as a form of vital introspection, which led to her first published volume Personal e Intransmisible (1999).

The artist considers poetry to be the building block of her practice, with many of her earliest performances developing out of her pre-existing texts. These include I will shout it to the wind (1999), an act that saw her suspend herself from an arch amid the throng of Guatemala City and read her poems aloud without a microphone, thus calling attention to the continued silencing of women’s voices. For Regina, the development of performance works was a way of channeling the deep-seated rage she felt following the 1996 peace accord. After 36 years of civil war in Guatemala, in which over 200,000 people were murdered, 83 percent of whom were of Mayan descent, the perpetrators escaped justice.

My body was the tool I had within reach.

When recalling those first actions Regina explains, “My body was the tool I had within reach. At that time, I had too much anger and ideas locked up, I had too many things to say.” She considers her bodily performances to be a place of “public interaction,” while the written word remains a profoundly personal act.

Her own body is central to her practice

Encounters with ground-breaking artists such as Ana Mendieta and Teresa Margolles helped Regina grapple with the agency that could be found within her own body, one that, as a woman, she found was constantly under public scrutiny, both as a site of violence and of objectification. “Being a Guatemalan woman is what has prepared me for a constant fight,” she says. “Guatemala gives us all kinds of tools to face the violence and the everyday danger.”

Meeting Marina Abramović also proved fundamental in Regina’s approach to structuring her performances, treading an often-delicate line between fostering empathy and pushing viewers to the brink of overwhelming discomfort. “Abramović was a fundamental stone in my thinking structure, and also in the way I understand performance. Her formal rigorousness set a path for all the artists who came after her,” she says. The influence is clear in works such as Bitch (2005), in which Regina carved the word “perra” (bitch) into her right thigh, thus invoking the all-too real association with the often-mutilated bodies of murdered women. Similarly, 279 Blows (2005) involved the artist entering a cubicle and striking her body 279 times, one for every Guatemalan woman who had already been killed that year. Audiences could hear, but not see, the act of flagellation.

Inflicting personal suffering in such a physical manner has meant that Regina, much like Abramović, has often been pigeon-holed as a masochist, when in fact the pair share an analytical, conceptual approach to performances, in which the body is nothing more than an instrument. The flesh becomes a means of conveying a more complex idea, while evoking a visceral response from the viewer. “The human body is the center of all concerns,” Regina explains. “That is why performance can create empathy channels quickly. The body of the performer is a reflection of the body that witnesses the action.”

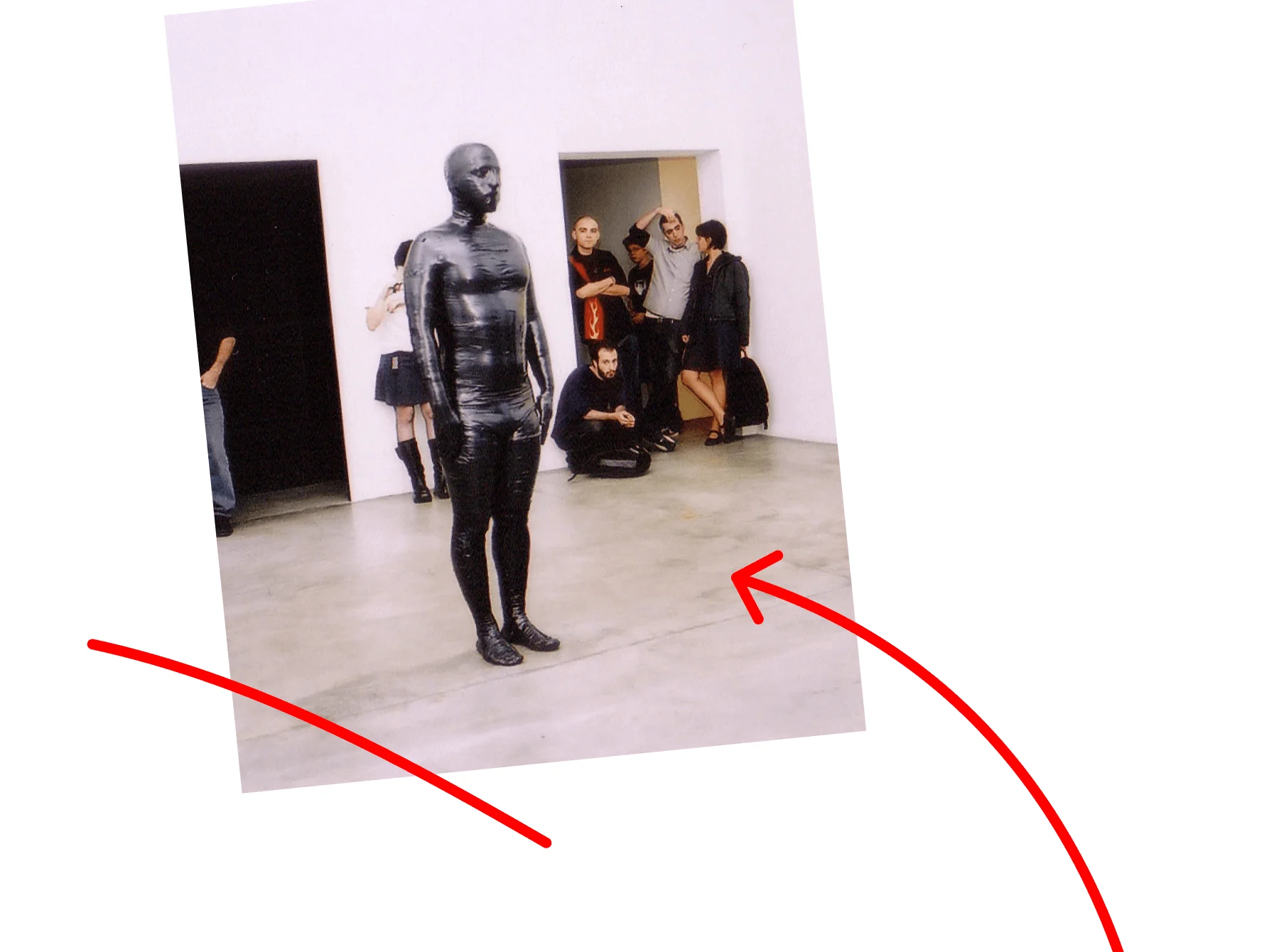

She redefines the parameters of performance

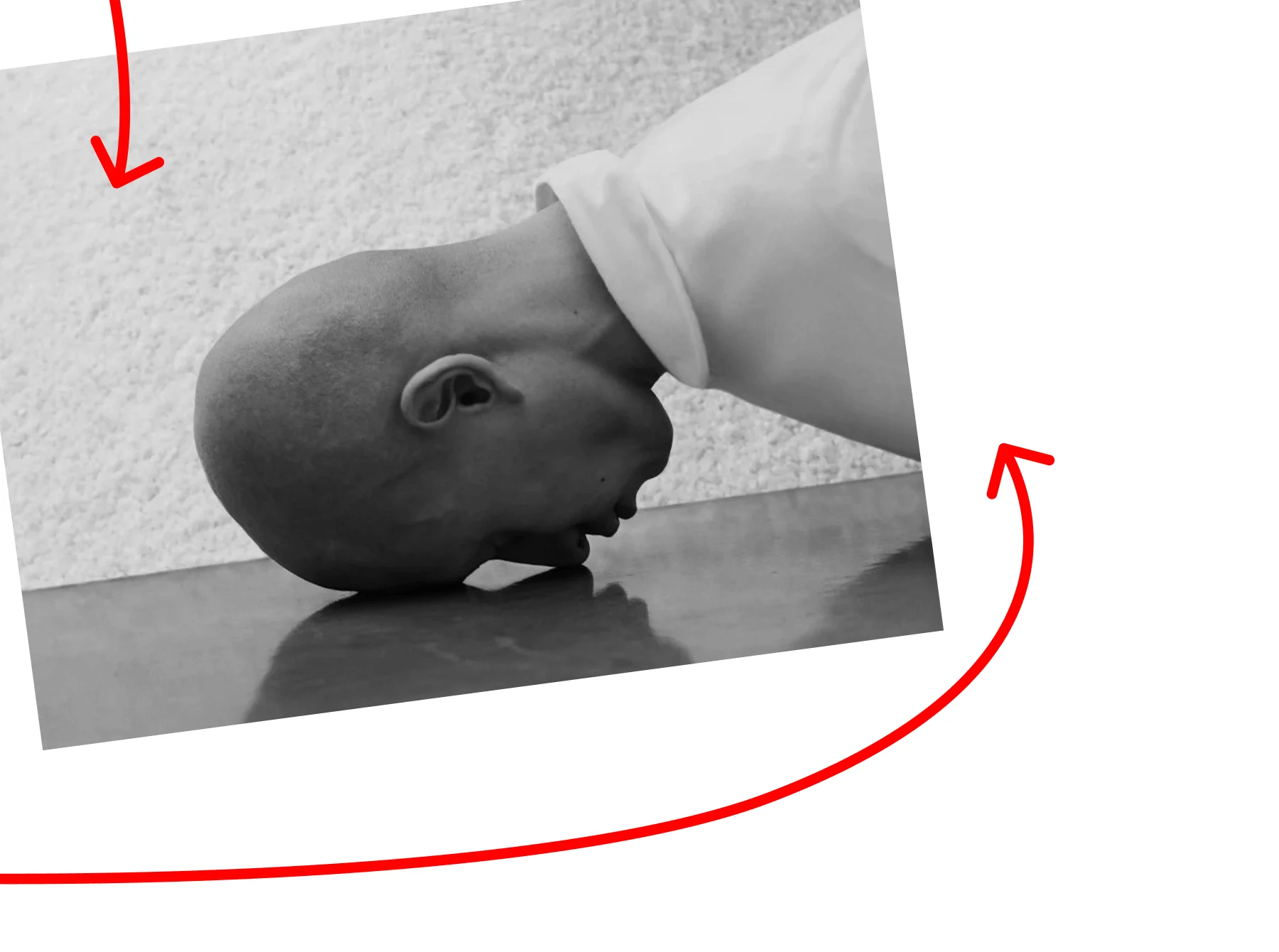

That being said, some of Regina’s most extreme performances test the parameters of the art form, by offering complete control to third parties. These include Blind Spot (2010), a work that sees the artist stand nude on a plinth, while an exclusively blind audience experience her body through touch as opposed to sight. The result was not only an interrogation of perception, but of power, as Regina found herself subject to mockery and a threatening sense of unease. Meanwhile, in Confession (2007) a man subjects the artist to waterboarding, continually plunging her head into a vessel, with only moments of respite, in which she gasps for air. The severe distress is palpable, and directly references torture inflicted on inmates at Guantánamo Bay prison.

While these acts might be difficult to watch, the simple elements of each performance hold a universal power. Even without explanation, evidence of self-harm or notorious forms of brutality evoke an intuitive response, loaded with the global contexts of warfare and oppression. This concise approach, which Regina says originates in her obsession with the “cleanliness” that is required to construct poetry, is also evident in her radical decision to undergo surgical procedures. Himenoplastia (2004) was instigated after she saw disturbing adverts for hymen reconstruction and contacted a doctor who agreed to operate on her while being filmed, for an undisclosed price. The result is a grueling and gory video that draws attention to the hugely problematic obsession with virginity perpetuated in conservative societies, and the even more disturbing fact that this operation is often performed on sex-trafficked women and girls. These dark realities are further compounded by the fact that Regina suffered severe complications and extensive blood loss after the procedure.

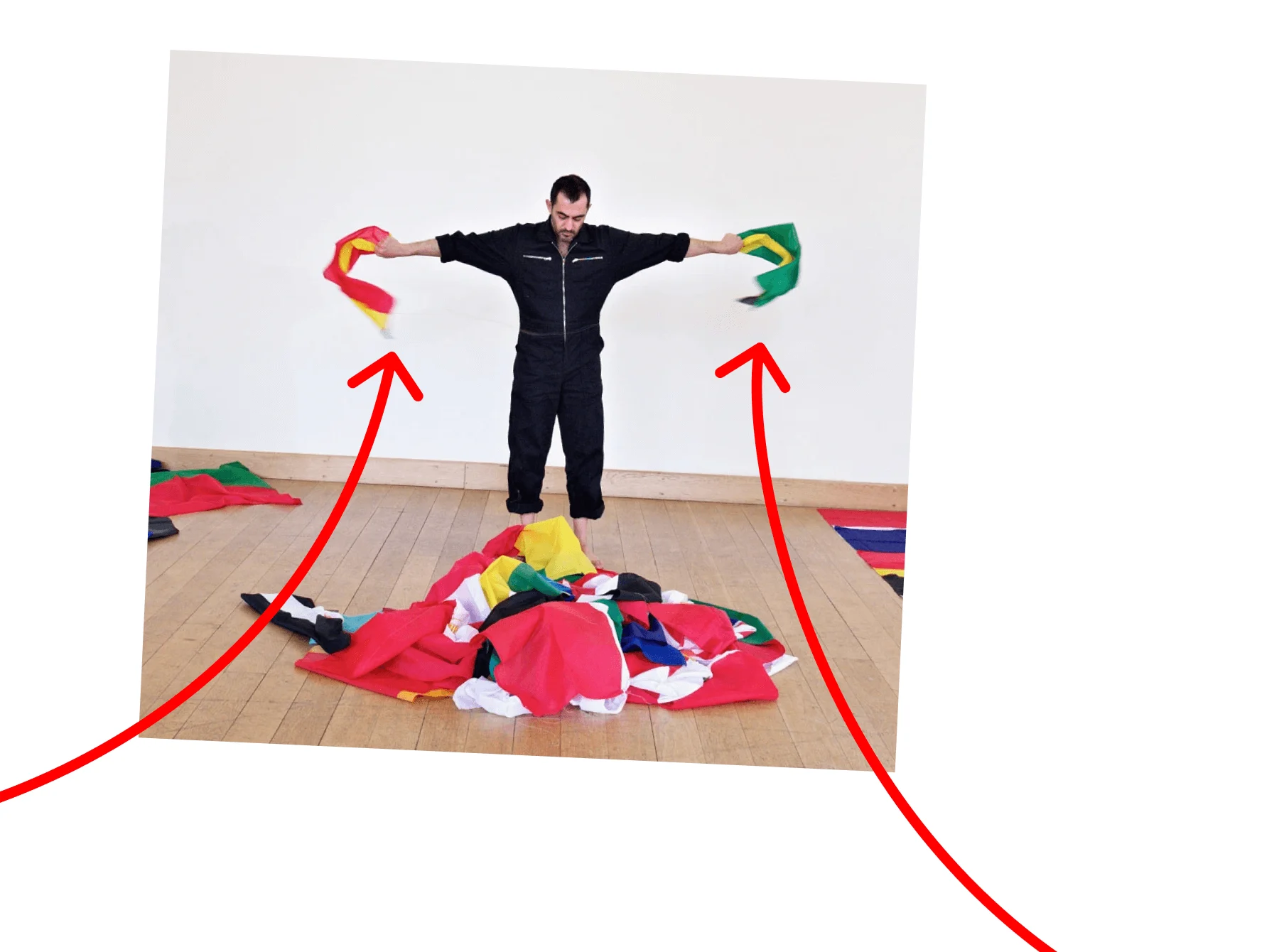

She interrogates injustice on a global scale

A few years later, the artist employed a dentist to drill holes in her molars and fill them with locally-sourced gold. She then traveled to Germany, where the eight pieces were removed. This transatlantic project, titled Looting (2010), addresses global cycles of ecological devastation, migration, colonialism and commerce, where the conceptual realities of extraction are physically embodied.

The clinical nature of these works also denounces the expectations around body-centric performance, in which the familiar female figure, with its long association as a subject throughout art history, is subverted. Seeing the inside of a dental cavity, or the bloody realities of surgical incisions, forces us to consider the body in an entirely new, utilitarian manner. The artist’s desire to dispel reductive interpretations of her physical presence also stems from her experience of being exoticized by the art world, with people only considering her work within the context of her home country, or an equally problematic, homogenous view of “Latin America.”

The desire to overcome these assumptions is one of the reasons why Regina so often performs among the general public, where unsuspecting viewers have no preconceptions surrounding what they are witnessing. She quite literally crossed this threshold with her 2001 work Skin, which took place at the 49th Venice Biennale. She began by shaving her entire body at the exhibition site in front of an audience, before walking the streets in a state of ultimate undress, submitting to the questioning stares of passers-by. “People on the street don’t know that it is a performance, they might not even know the concept, and it doesn’t matter,” she says. “What really matters is that they’ve seen and lived an aesthetic experience that took them out of everyday life and has generated questions within them.”

This was the case in her celebrated work Who Can Erase the Traces? (2003), where she walked barefoot through the streets from the Palacio Nacional de la Cultura to the Corte de Constitucionalidad, regularly dipping her feet in a basin of human blood. She left haunting footprints in her wake, which served as a specter of the crimes committed by Efraín Ríos Montt, a former military dictator, who was nevertheless allowed to run for the Guatemalan presidency. When she arrived at her destination, she placed the bloody bowl in front of the palace guards, leaving them to grapple with the image before them.

Taking art into the world, beyond the measures of a gallery or institution, demands a whole new facet of openness. In many ways it is more daunting than a controlled act of pain, because the reaction of the public can never be predetermined. However, this wider context is essential in building the “radical empathy” that Regina seeks to foster in specialized and general audiences alike. While her actions might often seem shocking or confrontational, they are ultimately about embracing vulnerability, and building emotional bridges in a world marred by inequality. Although Regina is often unsentimental about the limitations of art’s power to invoke real change, her impulse to make work never dwindles. She attests that we need “to disassemble the power symbols that represent oppression” and spark the questions and debates that can provoke that shift. “Art is an incendiary material,” she adds. “Our obligation as artists is to make it burn.”