Sculptor Max Leiva grew up in a middle-class family in Guatemala City. The third of four children, he was always restless, and his lack of interest in school forced his parents to move him around a lot, wondering when he would find a place where he felt like he belonged. Max wasn’t overtly creative in his youth, but he was attracted to the intricacies of strange items in the house. “Like the house vacuum,” he says. “I thought it had a beautiful form. I had to take it apart to leave it alone. That was the first thing I took apart, and there were many more after.”

His father was a dentist, and his office was filled with plasticine and wax for dental models, and Max would spend hours using this to create characters he imagined in his head. But despite these quirky flutters of creativity, art was never something he placed much importance on - growing up in Guatemala it wasn’t seen as a viable career path and this lead him in numerous directions before finally reeling him back in.

Max moved to Europe at the age of 20 to further a career in cycling which he had taken up during school. When this didn’t work out, he was forced to look elsewhere for work in order to get by. “I got a job as a mason's assistant in a cold military barracks, high up in the snowy mountains near Rivera in Tecino, Switzerland,” he says. He could not speak the language and knew nothing about laying bricks or mixing cement, and he could tell that his two seasoned colleagues didn’t want to talk to him. “From knocking down a wall with a mallet on the first day, it was work that made my hands bleed and showed that I had never worked in my life,” he remembers.

One fateful day, though, lead to Max reevaluating his choices. One of his colleagues had a bad fall and when Max went to help him up he swatted him away, shouting angrily at him that he was still young, that he should study something and not let himself get old doing hard work like this. “Nothing that my father had told me had ever had as much of an effect as this,” he recalls.

Still processing this advice while living remotely in the barracks, coupled with the surprise death of his father only a few weeks later meant that Max didn’t put up a fight when he was called up for military service soon afterwards. He served his time that same winter in the mountains of St Gotthard. “I thought it would be the best place to reflect on my life,” he says. While there, he began drawing portraits of famous rockstars in his spare time, soon aspiring to be a cartoonist in one of the magazines the soldiers received in the mail. He continued to draw, and when his service ended a year later decided to return to Guatemala to attend the Rafael Rodríguez Padilla Academy of Fine Arts, studying a general arts degree. At this point sculpture - which would come to define his life - didn’t interest him.

In fact, he avoided the practice whenever he could. When his course required that he commit some time to sculpture, his lack of interest in it nearly cost him his degree. Max wanted to get it out of the way, so he went to the library to look for references, and came across a drawing by Leonardo da Vinci of a man screaming, most likely one of the sections from the Italian artist’s long lost painting of The Battle of Anghiari. He was instantly captivated, and this discovery proved to be a turning point for Max, marking his first foray into sculpture. “What I saw as just a simple necessity ended up convincing me that my vocation was really sculpture,” he says. “It’s difficult to put that feeling into words... a kind of certainty that accompanied me in the most difficult moments and helped me to continue on this path and give shape to that passion.”

With no teachers in the academy able to give him what he needed to pursue his newfound passion, Max decided to ask the late Dagoberto Vázquez, who had studied at the same academy long before, to be his personal tutor. They met once every week, and Max would learn the ropes alongside his course work. He later applied for an Unesco scholarship to study at Silpakorn University in Bangkok, where he spent two years developing his interests in sculpture, and his love deepened. “I was also able to meet many colleagues and young professors and discuss artistic issues in sculpture from a very different perspective than we have in the West,” he says.

After returning to Guatemala and finishing his studies, Max began teaching sculpture to others in the same way Dagoberto did with him. After a few years, he opened an academy of his own where he lived and worked.

I’m fascinated by the human essence, our very condition, our fragility and behavior in society.

Having lived such a rich and diverse life, Max’s work contains a plethora of influences and inspirations. “There are elements that associate my work with other cultures, but I believe that is unconscious on my part,” he says. “I grew up in a multicultural home.” His parents preferred to speak in English, but Max emphasizes that Guatemala is packed with a huge variety of ethnicities, and that Spanish is by no means the only language spoken. “There’s Kaqchikuel, Mam, Zutuhil, among many others,” he says. “I don’t speak these languages but every Guatemalan who has grown up here has had contact with these peoples of pre-Colombian heritage, and we all share stories and experiences with one another.”

Like his life, Max’s work has changed course throughout his career. His earlier work reflected positive themes. “I was inspired by more idealistic things and worldly scenes, sometimes full of romance and passion,” he says. His sculptures were highly polished with smooth textures and rounded edges. Today, he still pulls references from this older work, but has new motivations now. “We all change with the passage of time,” he says. “Some events transform you and I am aware that I am not immune to these realities.”

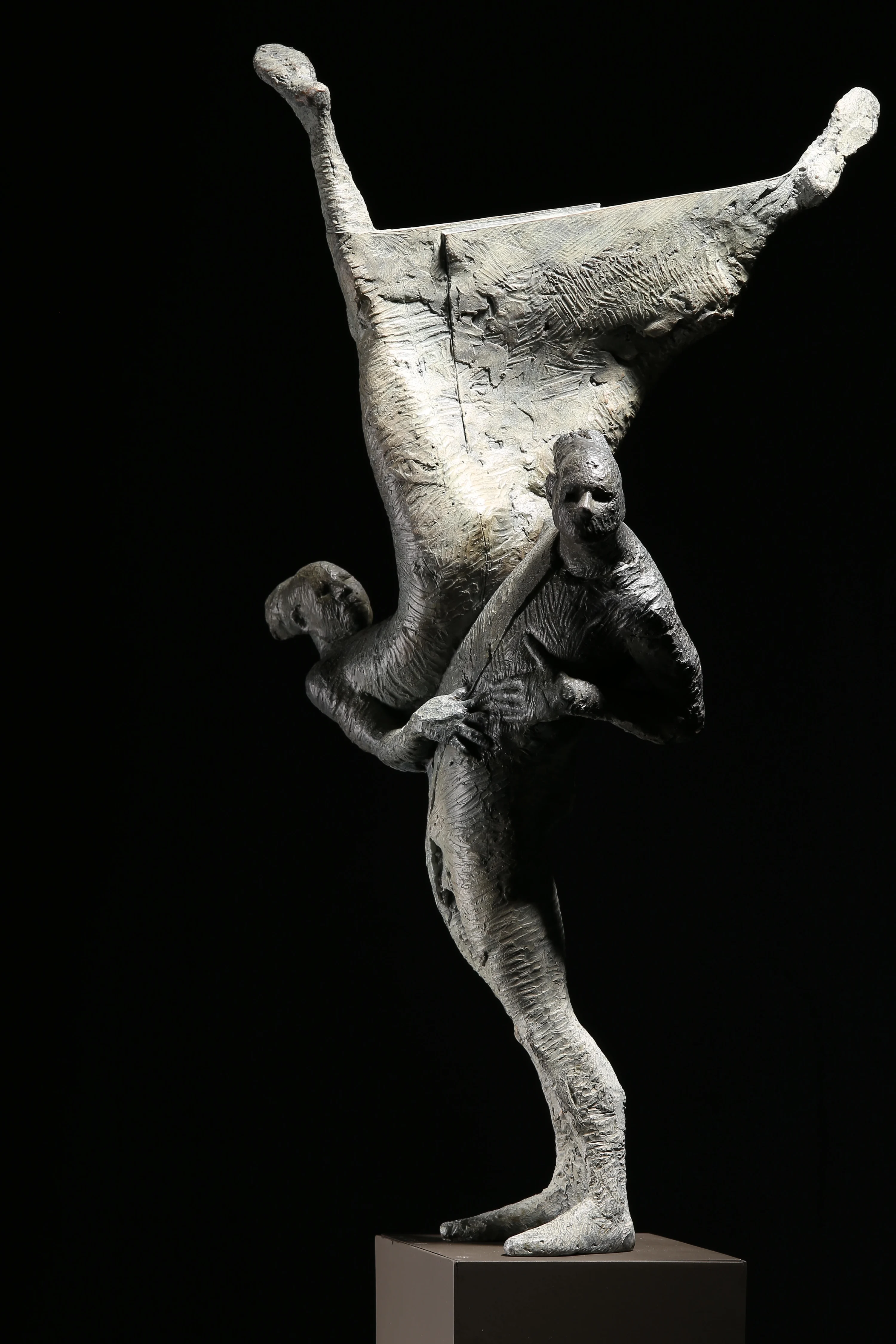

His latest work certainly has a different air to it. He includes more figures, and they are often faceless with distorted bodies. Look closely and you’ll get the feeling that many of the pieces also have a sense of foreboding to them. This mindset developed while he worked on a personal exhibition entitled Thieves in 2003, in which Max started to think about aspects of society that are more difficult. “The first characters appeared carrying objects, and they represented thieves taking things very quietly,” he says. “Not necessarily losses related to material things, but also the loss of freedom or life.”

Since that exhibition, Max tends to include more and more characters in his work. Some place comforting hands on one another’s shoulders or stand in groups looking around sheepishly. Some gesticulate madly or climb on top of each other, creating wild shapes with their intertwined bodies. “I’m fascinated by the issues related to the human essence, our very condition, our fragility and behavior in society and the realities which sooner or later we will all face,” Max says. He tells me he’s disturbed by existential dread, by unanswered questions, and these themes - although subtly - are visible in his work.

It’s hard to explain how, but stare at the different sculptures he crafts long enough and that sense of his own personal turmoil begins to resonate. “I do not try to define a precise situation with my works, I prefer that each viewer applies their perspective and creates the meaning that best suits him,” he says. “The interpretations that arise are always enriching.”

By Max’s own admission, the arts have never been particularly well supported in Guatemala, and although he says things have been improving, he tells me that “both government and public institutions, as well as most private schools do not include artistic education or promotion in their agendas.” Expectations for a Guatemalan artist are often low. Max is a special case, though. His path has been full of uncertainties, and it has not been a structured one, but this in itself has allowed him to flourish. As he says, “few things go unnoticed to the eye of a sculptor” and all of that life experience has come together in his work. “It is true that the personality will always be the sieve by which all experiences can become transformative,” he says. “The arts can exert a transforming power in people.”

Words by Alex Kahl.