Ianês’ work is risky and unpredictable. The public is not passive; he transforms them into the work. Ianês proposes conversation between various cultures, institutions, and the public. This results in large scale, communal installations.

Maurício Ianês is not afraid of failure. In a world where tangible outcomes and visible self-control are markers of success, the Brazilian performance artist pursues the opposite, instead inviting the public to engage in collaborative action, where concepts of “right” or “wrong” behavior are done away with, in favor of expression, impulse and instinct. Writer Holly Black tells us why his work is so important.

He switched painting for performance

Maurício grew up in Santos, Brazil. His artist mother taught him to paint from a young age, and by the time he enrolled in art school in São Paulo he already considered himself a painter. However, his world was turned upside down when his tutor introduced him to the work of Joseph Beuys, Marina Abramović and Chris Burden: artists who tore up the rule book and pushed the boundaries of performance. “I was in shock,” he says. “From that moment on I only wanted to perform.” These groundbreaking figures showed Maurício that the concept of art – and the role of the artist – had limitless possibilities. “Marina is a huge influence,” he adds. “Here is a true radical, doing things no one had ever done throughout history. And it is worth noting that at art school we were only really learning about men.” Marina’s complex understanding of aggression and pain, but also intimacy and peace, have long informed Maurício’s practice. Her astute interrogation of human relationships, in which a physical and mental transference of power can often become volatile (notably in the 1974 performance Rhythm 0) has been particularly influential on an artist who seeks to give control over to his audience, without any prescribed outcome.

Along with this avant-garde awakening, Maurício’s rather more traditional training in art teaching has shaped his practice, in terms of breaking down ideas around communication, sharing and building knowledge. “I didn’t know it at the time,” he says. “I thought those parts of the course were pretty boring, but my final presentation took the form of a performance, which set me on this path.”

He believes artists shouldn’t be idolized

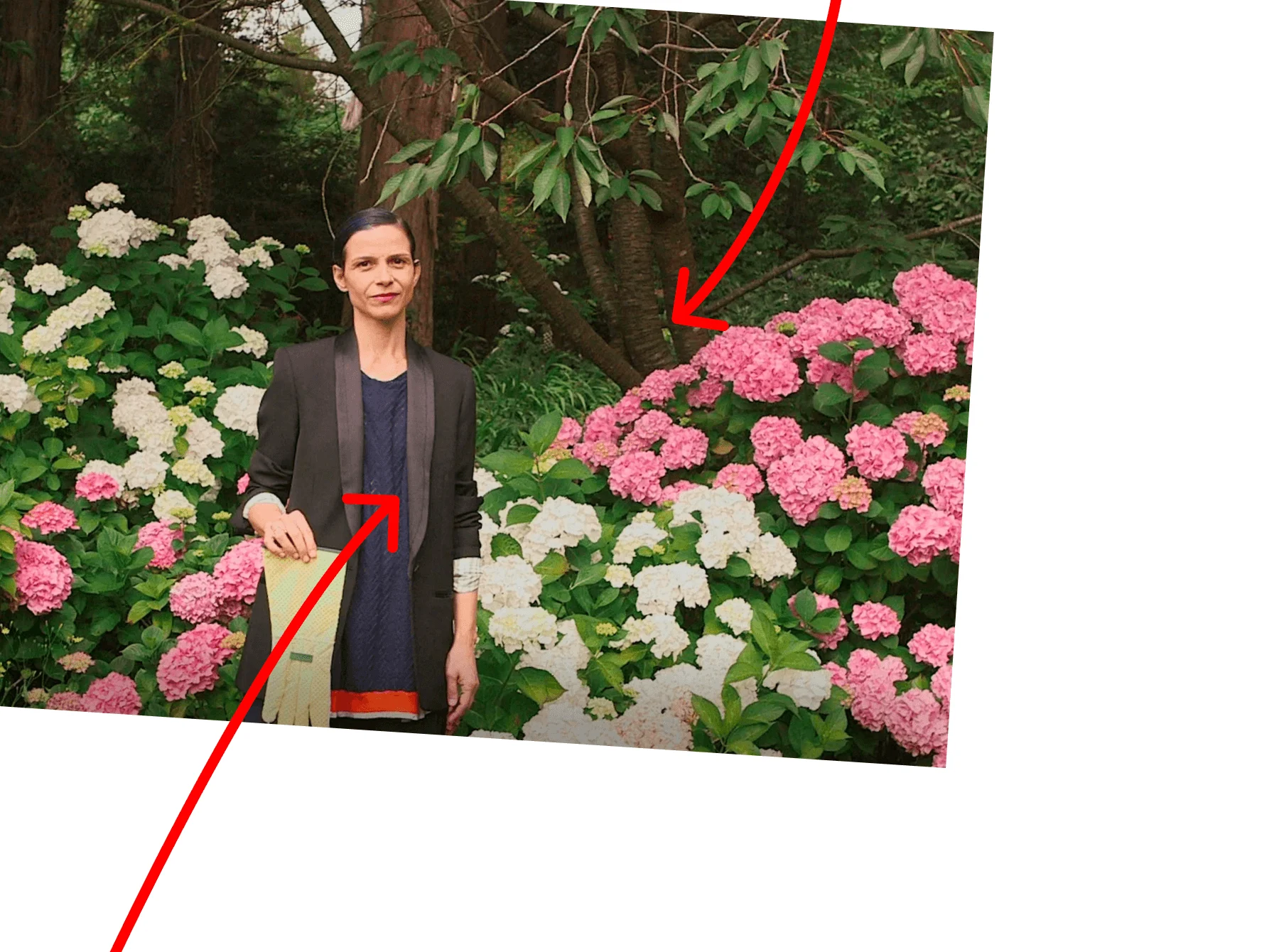

From then on, Maurício was determined to create work that collapses the barrier between artist and audience, or as he describes it: “knocking the artist from their pedestal.” He often avoids being identified, instead simply occupying a given space and speaking to visitors or passers-by in an everyday, conversational manner that focuses on their thoughts and experiences, not his. This interest in the possibilities of dialogue is married with an “absolute passion for language.” As a multilinguist, Maurício understands that the act of conversing is about much more than the words we speak. A different tongue can imbue alternate meanings, gestures, cultural codes and even influence one’s personality. “I feel like a completely different person when I speak a different language,” he says, “and art is a language in itself. It is a means of communication.”

Art is a language in itself. It is a means of communication.

Maurício even goes so far as to pull apart the definitions used to define his practice: “I hate the term interactive. My work is about collaborative action. It’s working together, producing something together. It truly questions the ideas of authorship.” He also prefers to describe his work as a series of “actions” as opposed to performances. “Performance is too associated with measuring effectiveness, like that of a car, or the success of the stock market. A museum director once told me that my performance was disappointing, in the sense that I wasn’t doing what he expected.”

His work is all about process

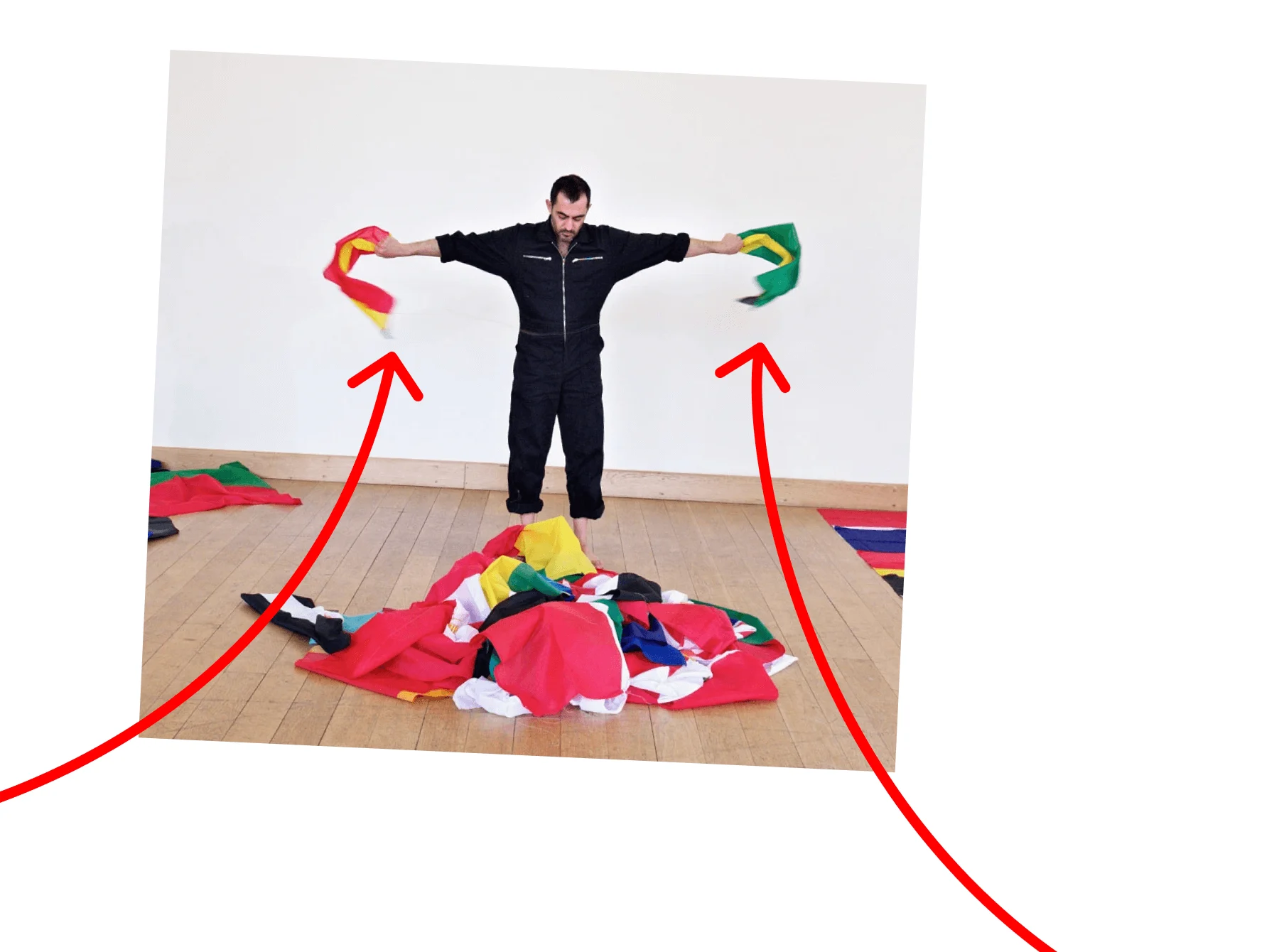

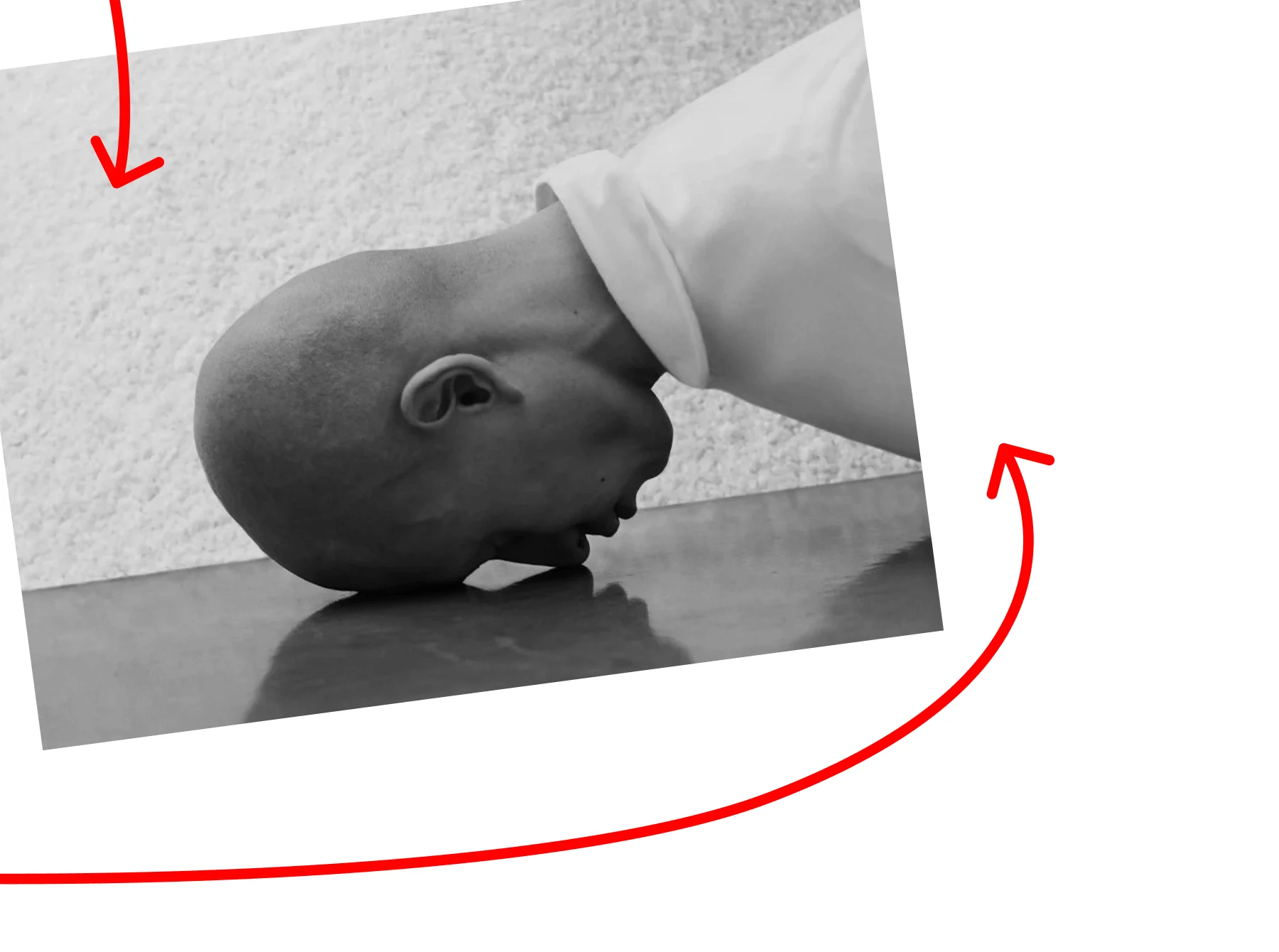

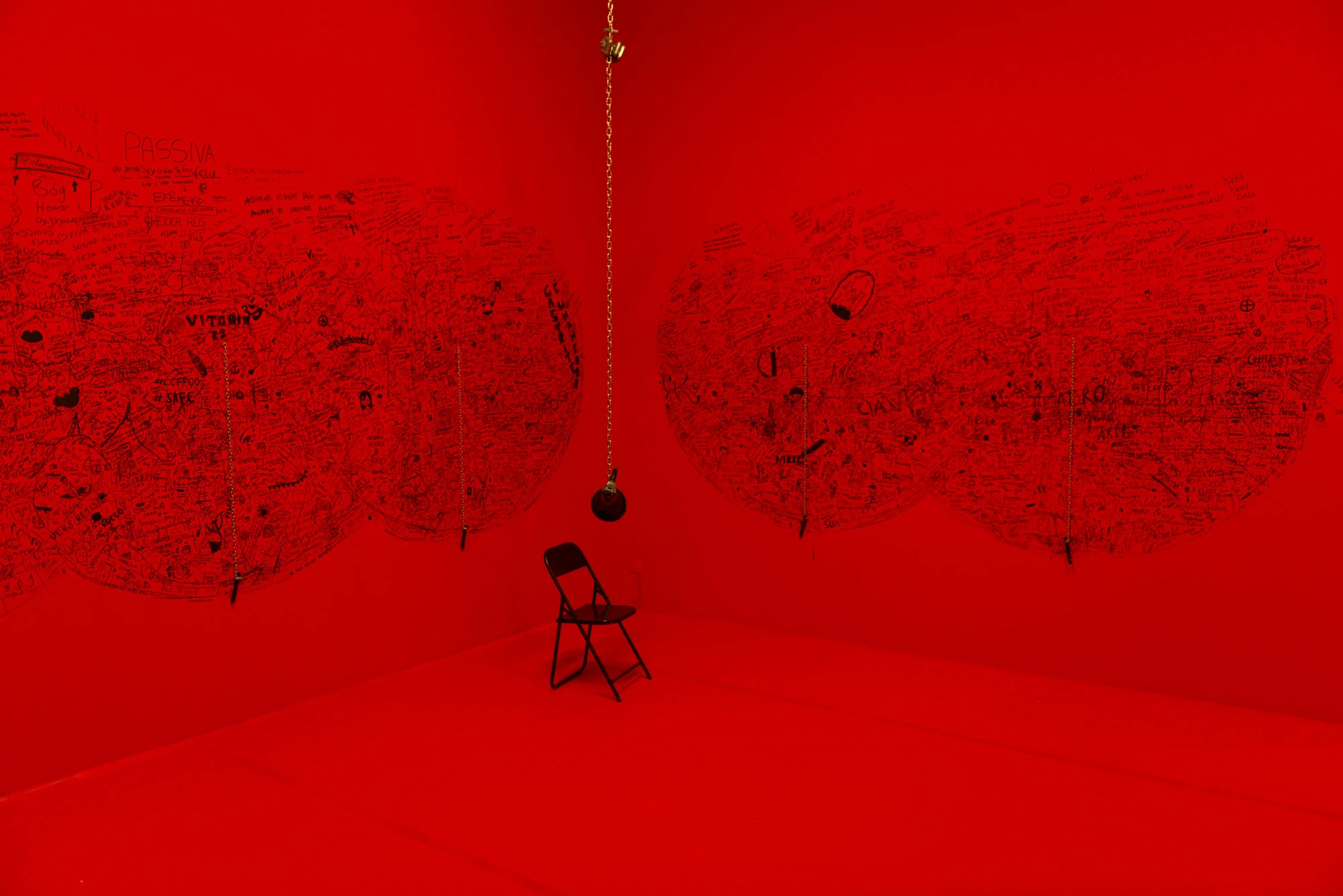

For Maurício, the art is ultimately in the action, not the outcome. Such intent is clear in one of his best-known works, titled The Bond. It was presented as part of Terra Comunal, a project conceived by The Marina Abramović Institute, at Sesc Pompéia in São Paulo. Within this cultural hub he created a space that was entirely at the public’s disposal, complete with food and drink, textiles, art supplies, tools and more. Even his own body was up for grabs. “I was in the space every day,” he says. “I had to redistribute the aura of the artist, just by going up to people and saying, ‘Hi, how are you, what is your name?’ and ‘This space is for you.’” The response was mixed. Some visitors were confused or shy, assuming that all other participants were official performers. Others took to making their own art, particularly children. People painted his body, began knitting, sprayed graffiti or simply sat and talked to one another. More extreme reactions saw individuals indulge their most destructive impulses. “One guy flew into a rage and began breaking everything in sight. Then he turned to me, with anger in his eyes.” Maurício recalls. “I thought I was going to get beaten up. Then he took a deep breath and said, ‘Thank you, I needed that!’”

Failure is essential to his art

This intense response shows just how powerful one can feel when liberated of the expected constraints of society, even if it is for a few short moments within an art gallery. While Maurício relishes being able to offer such a space, he is the first to admit that creating art which is defined by a lack of control can be challenging. “I have learned that artists never have control over how their work is perceived or interpreted,” he says. “That is very important to me. Failure is ultimately the promoter for change.’”

One such case, which Maurício describes as his “greatest failure,” took place at the third Transperformance festival in Rio de Janeiro. Instead of staging his work within an arts institution, he set up a picnic in a public square, in the hope that a cross-section of people would sit and converse with him. Instead, he was joined only by the city’s homeless, who assumed he was part of an aid organisation. “We ended up having a very interesting dialogue, but I had to explain that I was an artist. I was paid to be there, and I was staying in a five-star hotel,” he recalls. “I had wanted to create a situation that was about sharing and being equal, but it was clear that there was a huge distance between me and these people who were living on the streets.” Although Maurício considered this a failure in the sense that the outcome did not fit the original proposal, it was a defining moment. “It was a massive rupture; it was life-changing. I had to rethink all of my ideas about equality and collaborating with the public,” he says.

This was not the only time his pursuit for real human connection – as opposed to an interaction between an artist and a viewer – has proved a huge challenge. During the 28th São Paulo biennial, Mauricio decided to live on-site for the full two weeks of the exhibition. He arrived naked, with no possessions, and relied on public donations to survive. The process was supposed to explore kindness and co-dependence, to break down barriers and form intimate bonds. Instead, he found himself being treated like “some kind of guru.”

He harnesses the power of public interaction

It might seem strange for an artist to relinquish more and more control over their work, particularly when the outcomes stray so far from what they originally imagined, and yet it is exactly this response that makes his work so profound. Each and every one of his performances is rooted in a belief that art is for the public and should ideally be by the public. He upends the didactic notion of a genius artist imposing wisdom upon an audience, and instead seeks to show that everyday action – and everyday people – can create a valid form of art.

Never was this truer than at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris where, for the group exhibition Something Less, Something More, Maurício sat in a public seating area and invited visitors to come and argue the case for having their entrance ticket refunded. Not only did this unusual event give the public the rare chance to act upon any dissatisfaction, but it also challenged the strange relationship art organizations often have with the public and private sphere. “I felt uncomfortable with the idea that people had to pay to visit, yet still witness all of this corporate sponsorship,” he explains. Hence the need to provide a means of reimbursement, with all the bureaucratic problems that it entailed. To put it more plainly, Maurício says, “We love to say that art is political, but when it comes to talking about the politics and economics of the art world itself, let’s just say it remains taboo.”

Since the outbreak of the pandemic, Maurício’s work has taken on another political dimension, which many of us previously took for granted: celebrating the vital nature of human contact. “My work is defined by people being together, hugging and laughing, eating and drinking. Who knows when we will be able to do this again?” It is a sobering thought, but he is confident the day will come, and that the power of his art is defined by a physical togetherness that is impossible to replicate online. “I have avoided experimenting with any kind of online action. This is a chance to pause, to reflect and rethink this whole situation.” For an artist who embraces the disastrous and unforeseen, the future is full of possibilities.