For years, Argentinean illustrator María Luque had an artwork by the 19th Century painter Cándido López hanging above her bed. Her great great grandfather Teodosio had served alongside the artist in The Paraguayan War. When Cándido was injured very badly, Teodosio, who was a doctor, had to amputate his right hand - the one he used to paint with - to save his life.

Learning to use his left hand, Cándido was able to paint many of the sketches he‘d made of the war , artworks he became well-known for. “He painted incredible, huge scenes full of tiny soldiers preparing food on the camp or washing their clothes,” María says. “I first saw them when I was a kid and they got stuck in my mind’s eye.”

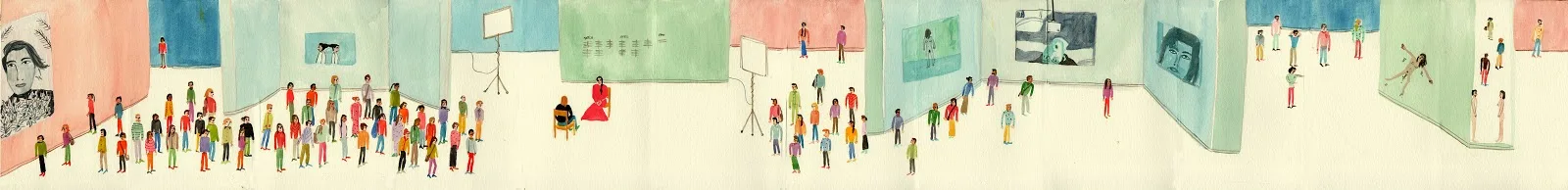

The scenes she paints herself are also inhabited by people made small by their surroundings. “I like the narrative possibilities of scenes full of people, a lot of things can happen at the same time.”

For her first graphic novel La Mano Del Pintor (The Hand of the Painter) María imagined an extended version of Cándido’s story. In the book the artist asks for her help to finish his paintings and they become friends. He tells her about his experience of war and teaches her how to paint with oils, in return she shows him how to make a fanzine and introduces him to ice cream.

María draws as if she’s a little bit possessed. “I like it to be intuitive, to feel that my hand is drawing by itself, not letting the head think about every movement.” As soon as she starts she already knows whether a drawing is going to work out. She never prepares sketches and goes straight to paper with her pencils or paints.

Fascinated with art history, María spends a lot of her time in museums hosting drawing workshops, watching people and painting other artists’ masterpieces. “I love everything about museums,” she says, “the silence, the cozy seats in the middle of the rooms, listening to guides, watching people taking pictures and of course the art pieces.”

She’s currently on an artist residency in St Petersburg, Russia where the guards of the museums are “the cutest old ladies, they all have adorable hats or scarves and they smile when you pass by,” she says. “I adore them.”

I realized that making replicas of other artists’ paintings was an amazing way to learn how to paint.

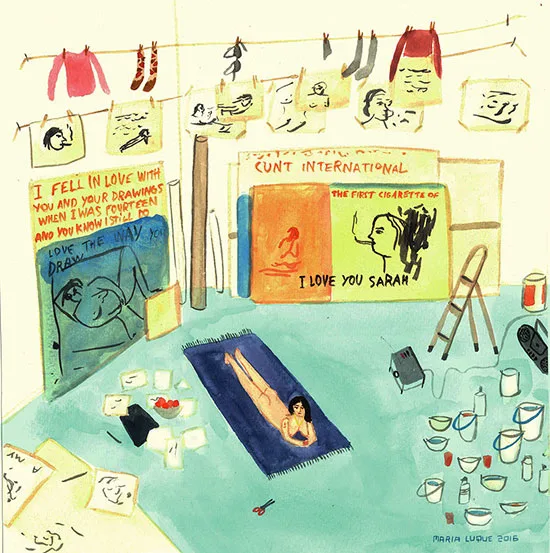

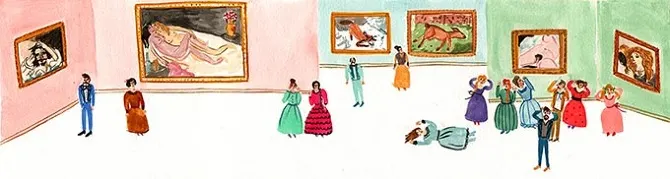

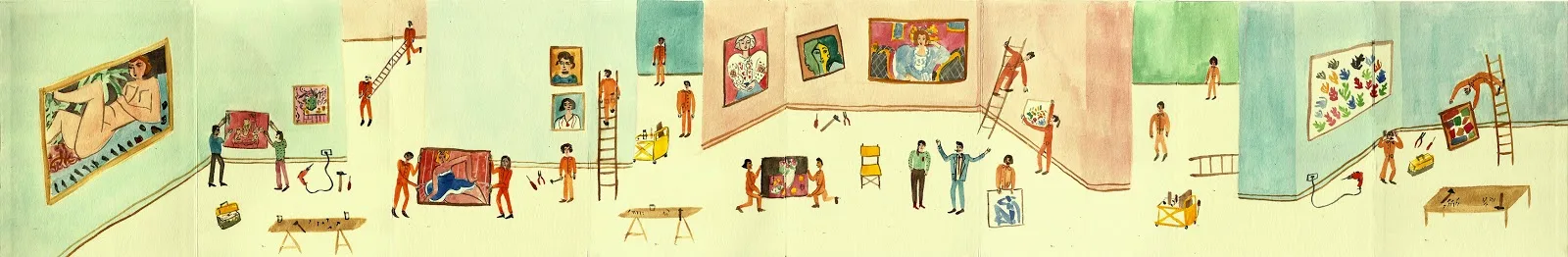

In one of her museum-inspired projects María painted a series of small watercolors set in art museums where things were going considerably pear-shaped. She imagined a calamity at a Marina Abramović retrospective and an accident at the opening of a Basquiat show. The detailed paintings are full of hidden stories, like “a woman in shock looking at The origin of the world during a Courbet exhibition, or a museum worker falling from a ladder while trying to hang a Matisse painting.”

Henri Matisse was a French multidisciplinary artist who was mainly renowned for his painting. He played key roles in some of the most significant artistic developments of the 20th Century, most notably Fauvism, the style of "the wild beasts" who placed more importance on colour than realism.

For each one she had to paint minuscule forgeries of the artists’ celebrated works. “It was really funny working on these paintings,” she says. “I realized that making replicas of other artists’ paintings was an amazing way to learn how to paint.”

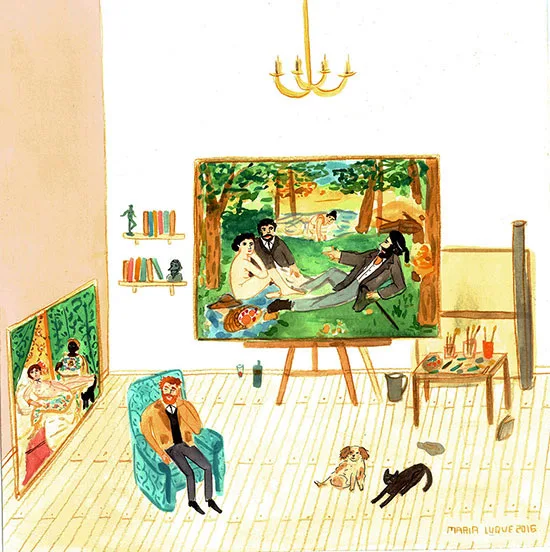

I love to imagine tiny moments, like Manet taking a nap on a sofa after painting Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe.

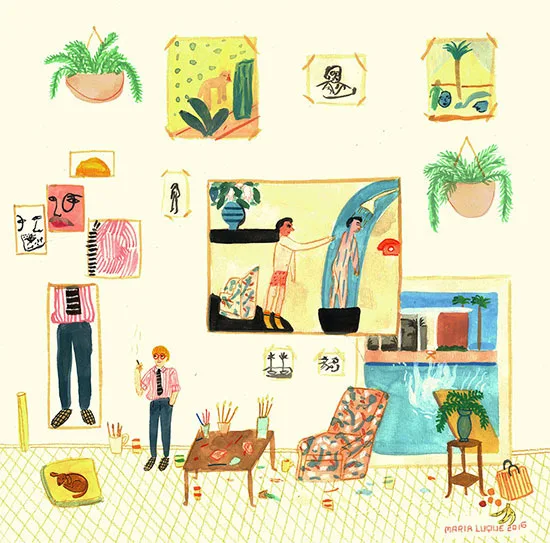

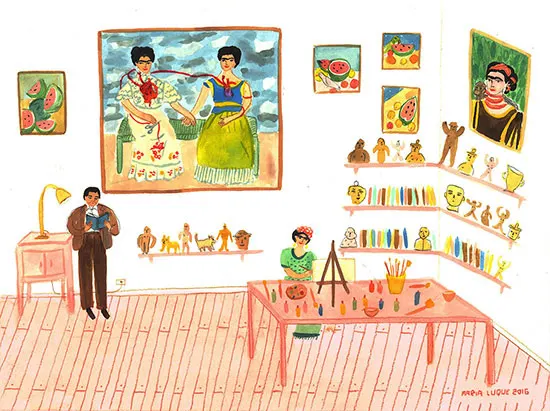

After this she became occupied with painting famous artists enjoying some down time inside their studios. Tracey Emin lies nude on a rug, while Diego Rivera reads a book. “I love to imagine tiny moments, like Manet taking a nap on a sofa after painting Le Déjeuner sur l'Herbe or David Hockney smoking a cigarette surrounded by his pets,” she says.

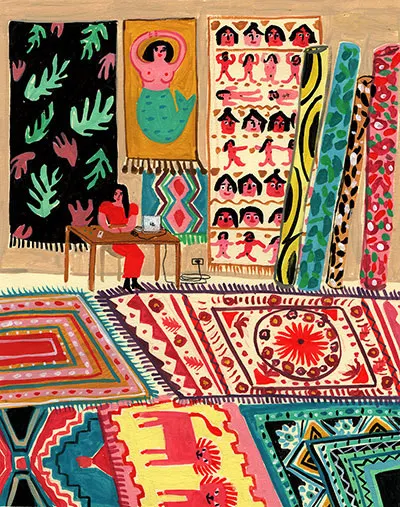

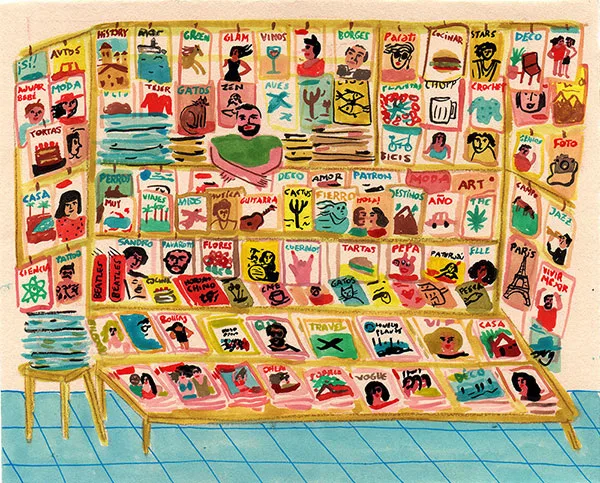

The detail in María’s works is astounding: in her drawing of an overflowing newsstand, the shelves are packed tight with her recreations of magazine covers. A drawing of a rug shop is layered with sophisticated pattern-clashing.

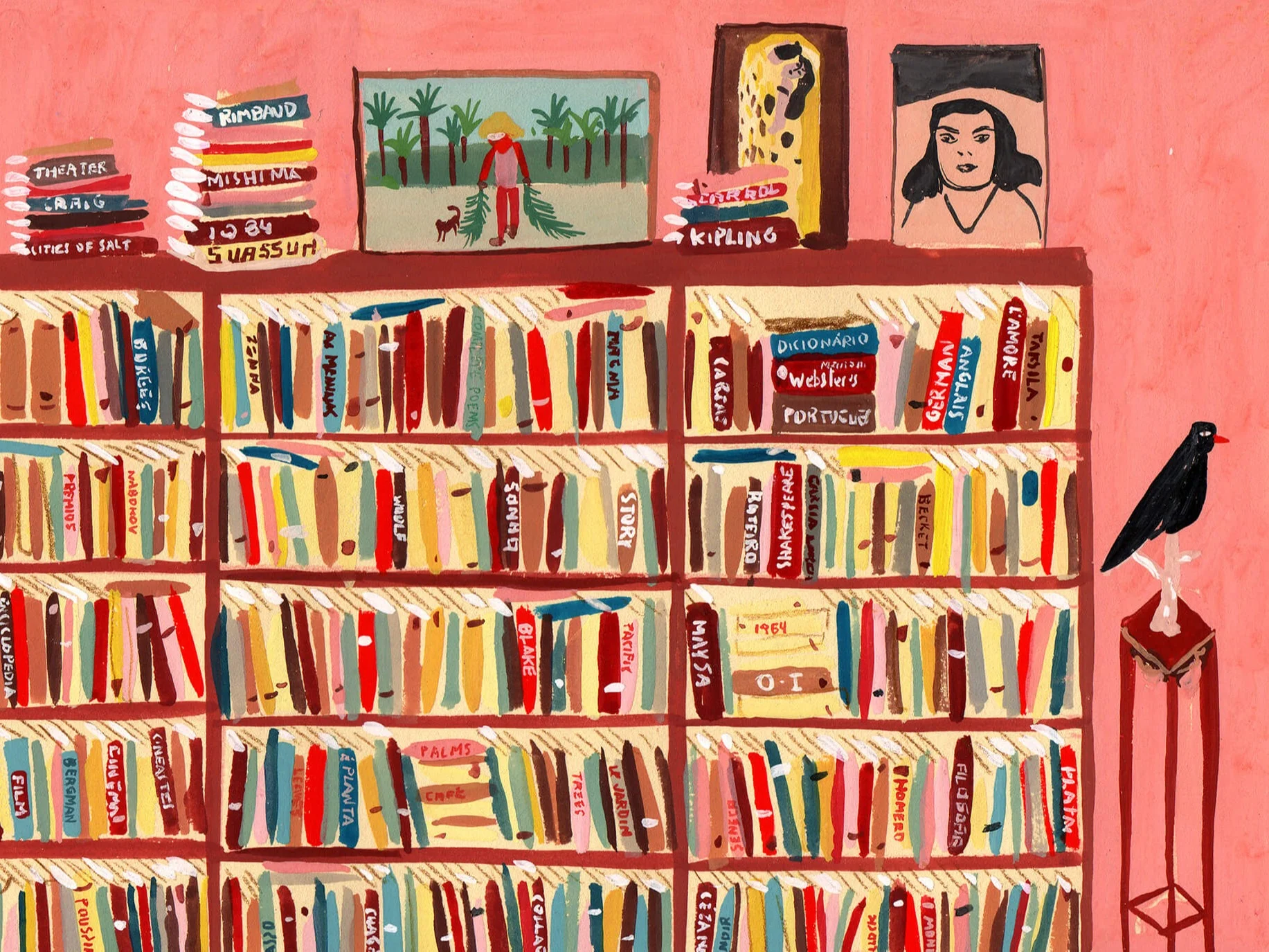

She has a particular fondness for bookshelves and what they reveal about their owners.

“They are so beautiful to paint,” she says. “On every bookshelf there's a huge array of different colors all standing next to each other.” She considers looking through someone’s personal library more intimate than rifling through their underwear drawer.

María gets her interior inspiration from her second job as a house-sitter. The interiors found their way in another book, her prize-winning, autobiographical graphic novel Casa transparente (Transparent house) which jumps around Argentina — Rosario, where she was born, Bariloche, and Buenos Aires — to Cusco in Peru and Mexico City.

A nomad of sorts, María doesn’t paint from a studio, instead she sets her paints down in different public spaces like coffee shops or libraries. “I started doing this when I realized that I really didn't like spending all day in my house,” she says.

“I used to get distracted really easily. When I'm working in public spaces I'm alone but at the same time I can see other people, listen to their conversations, watch them walk by through the windows.”

Words by Alix-Rose Cowie.