Since the release of the first film back in 1977 Star Wars has garnered a film fandom bigger than probably any other sci-fi community. And while the franchise has done much to bring fans together, it has also driven them apart, most notably in more recent years as fan criticism over their untouchable universe has reached fever pitch online. In this feature though, Alim Kheraj speaks to Annalise Ophelian, the creator of new series Looking for Leia, created with the help of a grant from WeTransfer in collaboration with Seed&Spark’s 100 Days of Diversity project, to explore the multifaceted and often forgotten side of the Star Wars fandom.

When Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker was released in 2019, one of the feelings that was pervasive in the mainstream was dread. Naturally, as the last film in the Skywalker Saga, a nine-film epic that began its life as a humble space opera in 1977 and has since gone on to become an intellectual property worth $65 billion, there was dread that the conclusion to this story would not deliver. But there was also a darker, more concerning dread: how exactly would the Star Wars superfans react?

It was a warranted concern. After George Lucas, the original film’s creator, sold his production company Lucasfilm – and the rights to his galaxy far, far away – to Disney in 2012, the equilibrium of fans had been skewered. Each film in the sequel trilogy has been marred by the reactions of certain fans, with actors like John Boyega, who played Finn, and Kelly Marie Tran, the first Asian-American to play a main role in a Star Wars film, hit with horrific racist abuse. The Last Jedi director Rian Johnson still gets death threats on social media about the creative decisions he made during that film. That fog of toxicity continued last year when The Rise of Skywalker was released, tainting the fandom and the discourse surrounding the franchise.

At least, this is the narrative that critics and the media would have you believe about the Star Wars fandom. But fans of a film franchise that has grossed nearly $10 billion can’t be solely made up of angry white men whose sexual maturity started and ended with an image of Carrie Fisher in a gold bikini. Surely, women and queer people and gender non-conforming people and people of color are fans of science fiction and space wizards. The question is: why don’t we see that side of fandom?

This was something that filmmaker and psychotherapist Annalise Ophelian was contemplating when she had the idea for her documentary series Looking For Leia.

“I am, myself, a geek and a fan and I think, like a lot of women and perhaps also women my age, we experience that in relative isolation,” she says over the phone from San Francisco. “Most of my life it's been a joke that I'm basically a teenage boy, and really I just sort of figured that the things that I enjoyed were a bit of an anomaly.”

Annalise, who has been going to fan conventions since the ‘90s, explains that when she visited Star Wars Celebration, an annual, Lucasfilm-backed convention, in 2015, she spent a large amount of her time with other women who were there by themselves just celebrating the thing that they loved. “It was really eye opening,” she adds, before laughing. “I was really surprised, and then I was really surprised that I was surprised.”

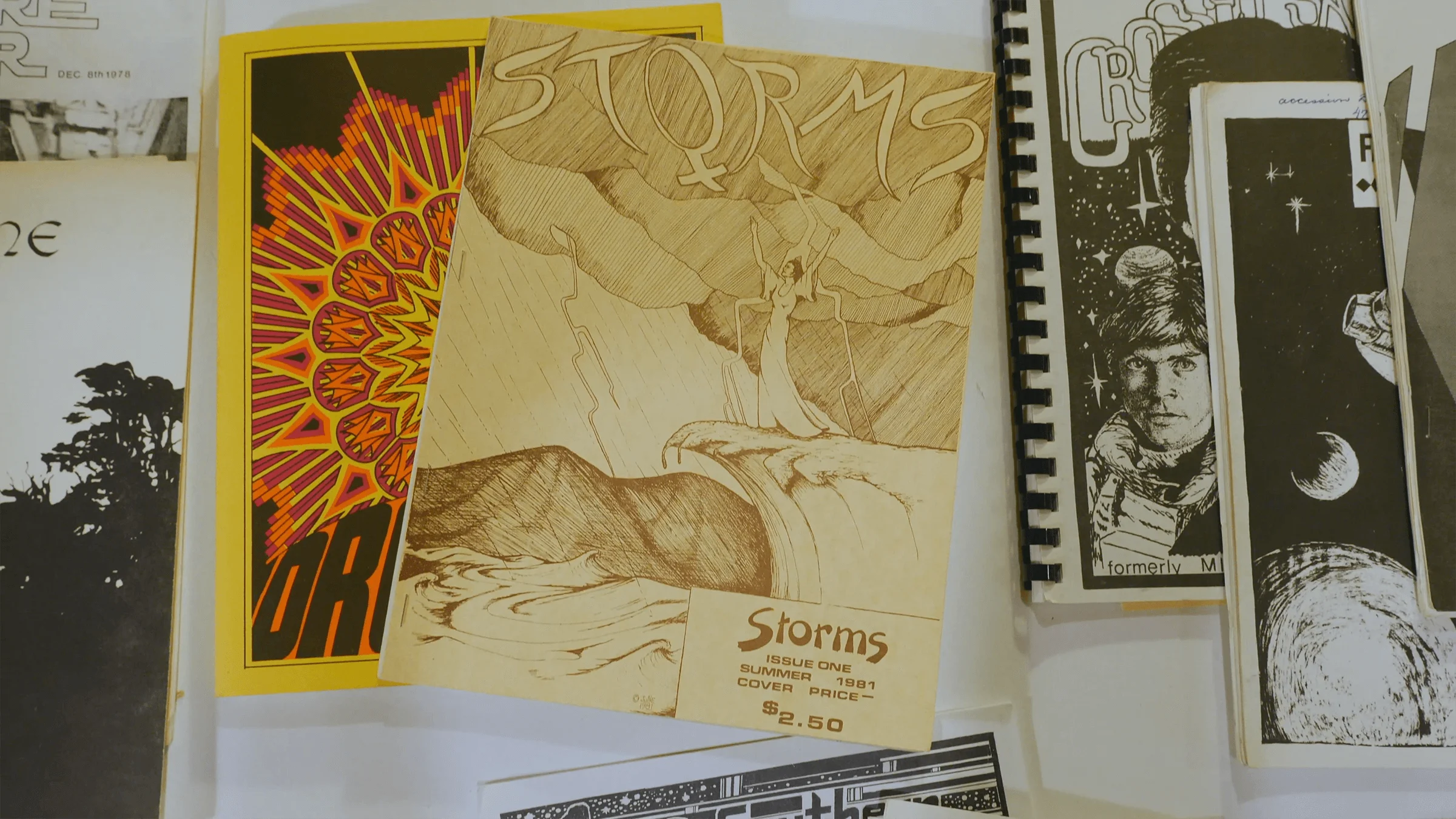

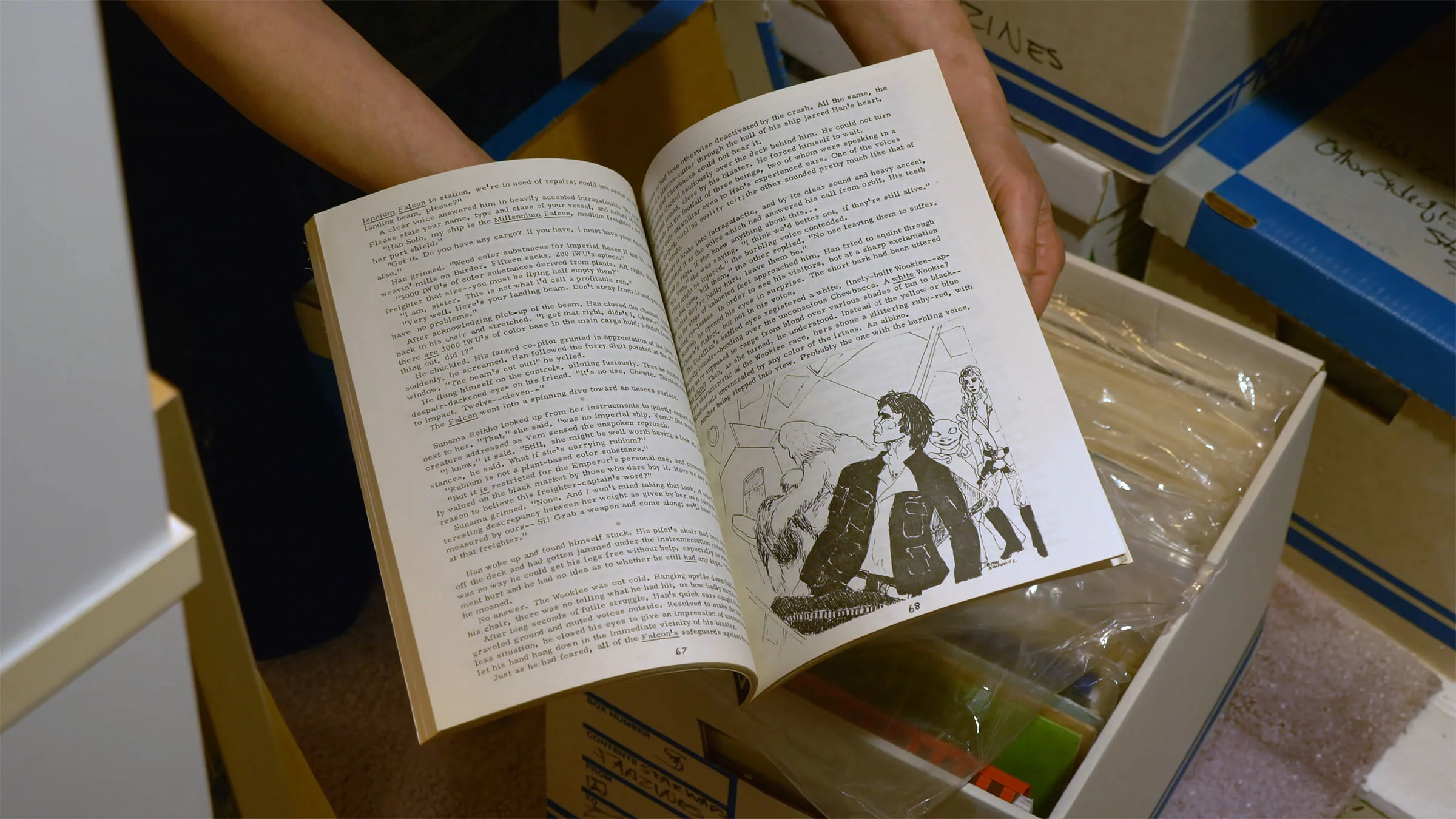

As a documentarian, Annalise saw an opportunity to shine a light on an overlooked area of fandom. As she puts it, public consciousness has looked at Star Wars through a “selective lens.” “I think the perception is because of who's been the most visible or the loudest or the most prominent,” she continues. “But if you look at the zine culture of the ‘70s and ‘80s, which very much emerged out of the Star Trek zines, it’s overwhelmingly a woman's domain. Those circles were women talking with other women, creating, arguing – you know, all the things we do in fandoms, fighting and playing in almost exclusively female spaces but without the attention being paid to it.”

Examining the Star Wars fandom, and fan culture as a whole, Annalise realized that the selective lens was not only tarnishing fan engagement with a negative brush but also diminishing and suppressing the voices and experiences of fans within those spaces who didn’t fit the stereotypical demographic. “It flattens a huge amount of diversity and experience,” she says, “and gives marginalised fans a message that you don't belong here.”

The first time you saw Star Wars and fell in love with it, that’s the true Star Wars for you.

Using people that she met at conventions, social media and word-of-mouth, Annalise conducted 100 interviews with women and gender non-conforming folk of all backgrounds. Condensing that number for the final project, she created Looking For Leia, a celebratory, inclusive and emotive documentary series that centers on what it means to love something and, most beautifully, how that love manifests itself. Across its seven episodes, Looking For Leia explores the various creative avenues that women and non-binary people tread while engaging with Star Wars.

Maggie Nowakowska was probably one of the earliest fan creators who gathered around Star Wars. Having been active in the Star Trek zine culture in the early ‘70s writing fan fiction (one of her stories was a satirical piece crossing Vulcan history with Tolkien), she turned her attention to George Lucas’ plucky space opera. When the first film was released in 1977, long before it was retroactively titled A New Hope and dubbed “Episode IV,” Maggie and her collective of science fiction fans didn’t know whether the film was going to have subsequent stories. It gave them an expansive, untouched universe to explore.

“Sometimes I feel like one of the first apostles,” she says, laughing. “Not to be blasphemous, but we had those first three years where the only thing we had was the first movie and some interviews that Lucas had given with Rolling Stone. So the universe was wide open to us; we could write whatever we wanted to. I was just saying to somebody online this morning that I don't really get too upset about arguments over canon because I was around during those first few years and we all made up our own. That’s what Star Wars was for us. I tell people the first time you saw it and fell in love with it, that's the true Star Wars for you.”

Of course, as Looking For Leia demonstrates, women and gender nonconforming folks’ interest in Star Wars is not solely about fan fiction. Christina Cato saw the first film when it was released in the cinema, and her whole family were Star Wars lovers. As an adult, she had been involved with the 501st Legion, a costuming group that focuses specifically on high quality recreations of iconic Star Wars costumes who do charity events, functions, and who are a staple on the convention scene. However, after getting divorced, she turned to droid building.

“It was a way for me to regain my independence and do something just for me,” she explains. “I had always loved Star Wars, but this was the first time I was ever able to actually express that. So it was a lot of things for me. It was therapy after the divorce, but also a way for me to learn how to be with myself and find joy in my own activities.”

Christina didn’t know anything about droid building. Researching online, she realized that she’d have to learn a number of new skills, not to mention sink a significant amount of money into resources, tools and 3D printers. Her first droid took 12 months to build. “You know, I always tell people, I cried a lot. I did,” she says laughing. “I bled a lot too. I was learning how to use tools I had never used before. I actually drilled a hole through my finger at one point.”

Having spent time online and at conventions, Christina was aware that in the droid building community – a niche but substantial facet of the Star Wars fandom – women were severely underrepresented. “Women would come up to us at events, usually young girls, and they would say, ‘I didn't know that other women did this’ and ‘I would like to build one but I've always been so intimidated.’’ That was a common statement.” Christina, along with three other people, decided to start the Stardust Builders Initiative, “an inspired, collaborative community of lady droid builders.” And while droid building isn’t cheap or easy, Christina says that when she’s at conventions and mothers and young girls come up to her and ask her about her droid, it’s the best feeling. “They get so, so excited because a girl did it,” she adds. “That really touches me.”

Preeti Chhibber saw first-hand the sort of resourceful creativeness that women and gender non-conforming fans could have. However, rather than tools and 3D printing, it was the internet that created a democratization of fandom for her. She recalls how, in those early days of the web, girls, many of them teenagers, learned HTML and coding specifically to create their own fan sites.

“The internet equalised a lot of us in a way and allowed us access to those fandom points that we didn't have when we were little,” she explains. “I could do fandom stuff on the internet, which meant that I spent my whole high school time and college time always talking about what I loved online. As we got more avenues to do that through social media and through websites and what have you, I started to realize that I had an opportunity to not only write about what I loved online, which I was doing anyway, but that I could also get paid for doing that. That was very exciting.”

If you look at the zine culture of the ‘70s and ‘80s, it’s overwhelmingly a woman’s domain.

Indeed, Preeti has been active in creating and forging spaces for herself, a second-generation Indian immigrant, in fandom. She has a podcast, Desi Geek Girls, with her friend Swapna Krishna, where “two Indian lady nerds, talk geek pop culture, with some Bollywood thrown in for good measure,” and she has recently crossed the boundary from fan to sanctioned content creator in the Star Wars and Marvel universes.

Tracy Deonn, who bonded over Star Wars with her mother growing up, and who is now an author and academic with a specific interest in fandom and fan studies, says that she has spent much of her professional life trying to decode why it is that the things we love inspires creativity in us. “I can't take full credit for this concept. I read it online somewhere and there was a fangirl who came up with this idea and I'm going to expand on it,” she says, before setting it out.

The creative impetus occurs, she suggests, because of how people interact with media. “I think there's a difference between a story and work. A story is something that humans have shared verbally forever,” she explains. “Stories are something that we share mouth to ear, person to person, family to family, and they are ideas that live in our minds – a narrative. And then you have the idea of a work, which is a much more recent product.”

Fans, Tracy argues, take the stories inside themselves, building interior lives around them that they want to share and interact with. “Not everybody does this,” she continues. “It doesn't mean to say that those people don't appreciate the story, but they experience the work and absorb the story away from the product. So the work is the movie. You might be obsessed with that two hour movie and the images on the screen, but you walk away and you're still thinking about the story then that's beyond the movie. That's beyond the container of the story.”

She also distinguishes between two types of fandom, generative and acquisitional, terms coined by Foz Meadows, a genderqueer fantasy author, essayist, reviewer, blogger, and poet. The nature of a film franchise like Star Wars means that acquisitional fandom, that is the desire to collect and gather information, products and merchandise, is endorsed by the official content creators. However, the rise of the internet and quick information sharing equalized things, and in this space generative fandom – creativity, cosplay, fan fiction and droid building – has flourished.

“I think generative fan works and zines are very decentralized,” Tracy continues. “So, you have people who are more interested in what other fans have to offer about the story than they are about what the official creator of the story has to say. And once you hit that point where we were creating our own websites, what made a fan made website that was well done any less valuable than one that was made by Lucasfilm? The difference was that one had the copyright symbol, but the fan generated one could have been just as robust, probably more so.”

There’s a gender split here, too. “When I look at cosplay and fanfic, which are probably the best examples of generative fandom, these are very female and gender non-conforming dominated spaces,” Tracy explains, adding that this could be because three-dimensional representation of queer people and women in Star Wars has, aside from Princess Leia and Rey, been lacking. “You can see how a fan is really interested in it might want to create room for themselves in that space,” she adds. “That requires you to make something. If I really love a character and I'd like to dress up as that character, but I know that character doesn't really fit me, then I might be inspired to write a story or create a costume that does fit me so that I can be in that world.”

While Star Wars has made a start on diversifying its universe, including more people of color and women in its main cast, there’s still leagues to go. Most importantly, it’ll never be able to accurately and wholly represent the different intersections that form the tapestries of human beings. And even if it manages to become some inclusive utopia, fans will still find the cracks in the story to create their own worlds and insert their own ideas.

“They get in like water and they find the tiniest crack of story opportunity, moment or glance and they will expand it,” Tracy jokes, noting that for her debut novel, Legendborn, a YA fantasy due for publication later this year, she has purposefully left those gaps for readers to explore.

Of course, fandom manifests itself in various guises. It’s one of the central themes on Looking For Leia, and perhaps something that should be remembered: There’s no such thing as a bad, or lesser fan.

Sharing her story in the documentary series, Bárbara Lazcano, from Mexico, told of how Star Wars was significant because it brought her closer to her mother, who was dying. Over the phone from Mexico City, she explains how she had grown up with the films, like all of us, and had been drawn to the character of Leia, but hadn’t really engaged with fandom outside of dressing up for events or parties. While her mother was still in a good place, and with a costume event coming up, Bárbara decided that she would ask whether, together, they could make a replica of Princess Leia’s iconic white dress from A New Hope.

Joined by her sister, she recalls how making the dress allowed them to laugh and forget about what was going on within their family. “It was just a normal thing that mothers and daughters do together,” she says, “and we haven't had that chance in a long time. That dress is representative of a very good memory of a good time spent with my family.”

However, while the dress has a deep personal significance, Bárbara says that wearing it is a different form of expression as it reveals who you are as a person. “When you walk around on the street wearing it, you get two types of reactions,” she explains. “It’s either, ‘Oh, I recognize myself in that,’ or people going, ‘Who is that ridiculous person walking around in a costume?’ It is very exposing, but at the same time it's also really nice to see there are people that are able to enjoy this, do this and to show to the world that this is something that is important to me.”

Ultimately, despite the different manifestations of people’s creativity in fandom, that’s the thing that binds it all together: A desire to share and create a community. Whether it is through zines, webrings, conventions, social media, Star Wars fans have been able to cross divides and forge relationships by creating and exploring inside the universe of the thing that they love. Even Looking For Leia is an act of creation that has forged a community among its creators and participants. It’s a reminder that amid the modern discourse and an on-going culture war that wages on in the press and on social media, fandom should be something that is celebrated, not castigated or derided. While those complaining and hurling abuse online might make the most noise, they are by no means representative of the majority, who are dedicated, kind and creative. They are the light to the darkside – long may the force be with them.