We all want to be liked. It’s human nature to want other humans to find you in some way appealing, moreish even – an appetizing starter on a menu that has people salivating long before the course is served, only to be devoured with gusto and the promise of a return visit. Our families and our friends are the first to offer us morsels of being liked, then colleagues, and the people we’re connected to on the approval matrix of social media. The like button is a sweet cordial in the great cocktail of appreciation. I have tried to bury all the tells of my need to be liked, to dial down the noticeable craving for admiration and acceptance, to act aloof and unbothered as esteem laps at my heels. When the slightest bit of criticism rears its gargoyled head I’ve been known to say; “well, you can’t be liked by everyone,” but that’s a lie we all tell ourselves so we can sleep at night. I want to be liked by everyone.

Most people in the public eye have a divided audience of lovers and haters. The yin of fanatics followed by the yang of harsh critics. Nobody strives to be moderate, because to be merely tolerated is to die, socially at least. If we can’t be universally liked, we want a Marmite return on investment; proof that we’ve stirred other people, the ripples of ourselves ebbing forever outwards. Settling into the role of Dr Jekylls or Mr Hydes. Beyoncés or Sasha Fierces. The two Victoria Beckhams in the video for Not Such an Innocent Girl. Once in a generation, when the planets align, a star is born who transcends popular divisions. Who somehow magnetizes all of us. Whose opinions don’t rattle. Whose privileges don’t irk. Whose smartness isn’t pounced upon as affected. Whose charm isn’t so slick it eventually calcifies. An all-round good egg. We rally behind them, nodding sagely at their perfectly landed jokes and coveting their lives. While the rest of us jostle for scraps of approval like Hungry Hippos, David Hockney is liked by all.

We’d all like to be a bit more Hockney, wouldn’t we? To be on everybody’s fantasy dinner party guest list and be the attendee who flings off John Baldessari anecdotes like After Eights over the coffee and utters casual asides about turning down a knighthood. Could he be the only person who doesn’t evoke the vitriol of the internet? His allure, his charisma is ingrained, rather than forced. He lacks the slick, wet facade of yet another Oxford-educated artist raised on champagne at private views. We all want charisma, it’s catnip for other humans. It builds communities better than a Tory government. But many people unsuccessfully attempt to puppet charisma’s shape. It’s a bit like casting your foot in plaster: the foot looks nice but it doesn’t have a pulse. Overly-trained charm lacks heart, it’s offensive. In art circles full of empty “love your work” platitudes, Hockney’s retained his integrity. He never seems to buy into the lovey-dovey bullshit, nor appears to be trapped in rolling out multiple “sellable” creations. His edges are amorphous: a painter, yes, but also a drawer, an iPad-er, a filmmaker and a photographic collage-maker. It’s a bit naff to call him a color Jedi, but here we are. His subject matter, listed out, can sound a little basic mum on Instagram. Tulips in a vase; seasonal blossom; sunbathers. But I find myself inhaling his scribbles, invisibly getting high on his Hoxygen.

Like all of us on Instagram, his work quietly endorses my aesthetic decisions. My current home renovation is peppered with sacrificial totems to the artist. I devour his nuanced hues before instantly colour-matching them with a Dulux app. Just the right green on the floor, just the right banana yellow for the venetian blinds, the desk arrangement just so. He doesn’t so much as invent colors, as let us see them anew. He is, for want of a better term, an influencer. Today’s influencer influenza often centers around athleisure, nude lipsticks and flat tummy teas; a choir of beige streetwear singing from the same hymn sheet. But Hockney is felt offline, in Farrow and Ball-kissed kitchens, an omnipresent Californian aesthetic (even in central London), lush potted plants in Crayola greens. He’s not here to influence, it’s just the natural repercussion of his restless, wandering mind and exacting eye. A striped jumper from Alexa Chung’s fashion line pays homage to the artist. With regards to a famous picture of him in a pink striped rugby shirt, she said she had “basically completely ripped that off for [a] sweater”.

But Hockney doesn’t care about being mimicked or even completely ripped off. He doesn’t strike me as a man to wistfully look back at his wake. He’s perpetually onto the next thing, adopting new media with the zeal of a teenager, even the divisive iPad has been added to his canon. And it’s not just the work that seduces us, he’s a man as in command of his own image as the ones he paints. There’s the impossibly blond crop, the nifty outfits, the great-fire-of-London heavy smoking, the benign grumpiness. A man we treasure as a nation, without the snagging benevolence of most national treasures. He’s contrary without being jabbingly controversial. He’s impossible to mimic and impossible to ignore. You might hear him sardonically quip about his legacy, but I suspect he’s not too bothered. He is the patron saint of salty nonchalance and, like gruel at the workhouse, you just want more. He’s a Friday night. He’s a bank holiday weekend. He’s two weeks on the European coast. It’s an irresistible alchemy, a captivating personality that doubles as a diligent agent of creation.

Don’t we all want to be great company with a fulfilling-but-exacting career? Hockney is a magimix of Hollywood cool and Bradford salt. His life story, glimpsed in his paintings, gleaned from interviews, is so much more than a serial of calendar months, in the same way his paintings are more than pigment on paper. His combination of creativity and eccentricity has always been lived with a lazy shrug. An insatiable, fidgety naughtiness like trying to get to sleep on Christmas eve. Tracing back through his catalog, we’re Hansel and Greteling through time, following the breadcrumbed history of a life as beguiling as it was aesthetically pleasing. There’s that certain, almost caricature-like mundanity to his early life. A working-class lad from a working-class family in industrial Bradford. He was blitzed, his earliest memory is of his mother screaming as they crouched under the stairs during a raid. Government-wide austerity meant rationing until he was 16 and he worked as a hospital orderly rather than do national service (okay, that’s not as run of the mill as the rest). I’m still unsure if being both tender and gruff is a Bradford thing or a Hockney thing, both countrified and urbanly pragmatic. The duality of Cathy and Heathcliff dales and underground miners in coalfields must have been infectious for young Hockney. Of the rural sublime and the traditionally meat-and-two-veg urban. Of naturally occurring practicality and naturally occurring pure romance. In 1959, a brunette Hockney with a pudding bowl haircut rolled into the Royal College of Art, smearing canvases with bold, colourful gestural works, each bustling with a scratchy homoeroticism little seen publicly. Figurative realism was out of fashion in the postwar landscape, but Hockney revelled in the form, deconstructing proportions to the point of critique, and warping perspectives. The rules of colour theory were torn up. There’s something spirited but not quite rude about Hockney’s pre-Pornhub torsos, a time before dick pics and Elton John and David Furnish and HIV and civil partnerships. A time of secret, satisfying, illicit liaison, a bit like smoking weed behind the bike sheds.

I adore Hockney with near-religious fervour. An art world deity with a peroxide halo. That blond crop hinting at his position as a glamorous Just William, unkempt, with the underlying assurance of mischief. Reflecting as much light as possible, barely shielding his naughty top-shelf sense of humour. The Barbara-Windsor-meets-overzealous-bolt-cutters look is a punchline of a haircut, the cream atop the milk. His face below, a perfect circle, repeated in his trademark round spectacles. Catch me standing outside his celebrity home because he sent me secret messages in his paintings. I pilgrimage to the National Portrait Gallery or Tate for sacred glimpses of his pool tableaus. I seek out Bombay vistas and Marrakesh scribbles like a junkie searching a fix. I have always preferred his drawings, with their implicit sense of time-constrained diarizing. An airport lounge. An iced tea between sights. The corner of a hotel room. See it, sketch it, move on. From this distance, he seems forever agitated, wanting to surge onwards once the moment is confined to paper. He’s a pro-smoker, chain-smoking Camels with their aesthetically jarring health warnings. Some of his drawings feel as snatched as cigarettes. An ashtray and a pencil is all he needs. Mischievous fag-scribbles before boarding a flight.

Hockney inadvertently manufactures aspirations, because he’s satisfying his own curiosity rather than ours. Every work is an invitation, a ticket to a well-lived life of indulgence, free drinks tokens at the Hockney bar. With each stroke, we’ve accessed the private pool, we’re inside the Notting Hill apartment, we’re browsing midtown Manhattan, we’re sipping espresso in Cairo, we’re strolling together on Mulholland Drive. Hockney seizes the opportunity to paint a vista in all its glory, but it’s rendered with witty asides, to celebrate beauty and also parody it. You’re privy to near-casual noticings unfolding meters from you, the clutter of a charmed existence neatly ordered for us to snoop. Hockney’s life unfolds as we merely watch. In The Room, Tarzana, we see boyfriend Peter Schlesinger’s latently sexualized bottom mid-impatient sulk. Who doesn’t want to spend a week abroad getting laid? Navigating that tempting dance of romance with a lover? Heightened emotion playing out as you retreat from the prickly heat of the day to push up against each other. The ebb and flow of two people away from normal life. Who doesn’t want this?

I don’t remember my first encounter with Hockney, but at some point I became a horcrux for his essence, which sounds sexual, but isn’t. Something about him took influential residence in my psyche at a young age. There’s a half-term drawing I did aged six of his infamous Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy painting when it was toured to the Brighton Museum. Mine is not a fantastic rendering – the pencil strokes are forced, the perspective non-existent – but I was snared. I’ve spent the intervening years (let’s say 24) trying and failing to turn my life into that painting. I want the ease of a laid back pied-à-terre in leafy London. Sunlit Georgian façades outside my shuttered window. Reclining in a modernist chair with a sneaky cigarette. I’m not one for ‘60s minimalism, but I’d like to have enough space for it as an option. A telephone on the floor is a must, but also a pain in the arse. Not every item of Clark paraphernalia was coveted. The shag carpet in it is more of a question than an answer because it doesn’t seem compatible with cats. I’m not fussed about flowers, especially lilies, and the table looks a bit IKEA. I’m splitting hairs now. The original painting is of Celia Birtwell and Ossie Clark not long after their wedding, where Hockney was best man. Peter Quennell in The New York Times reflected, “Like Hockney’s other works, it is pallid, spacious, cairn. From their quiet, agreeably furnished surroundings… the Clarks gaze out with expressions of reflective dignity.”

Hockney started making double portraits in 1968, realistic representations of couples in simplified depictions of their homes, cinematically staged insights into the mood of the time. In a world of deep fakes, it’s refreshing to see an un-augmented scene stripped back to a shorthanded reality. His work is the antithesis of misery, or dramatically breaking news. No extremes, no war, no famine. And he doesn’t even seem that enraged about his sexuality. No axe to grind about living through the AIDS crisis. He’s irritable, sure, like espresso on an empty stomach, but he’s not angry. He’s reveling in the everydayness of the people closest to him and speculating on the relationship of the sitters, niggling at their unspoken communication. Whether its novelist Christopher Isherwood and his live-in boyfriend Don Bachard, the American collectors Fred and Marcia Weisman posed like their acquired Henry Moores, or Hockney’s parents with his father’s fidgety feet mid-tap on the floor. Comparisons have been drawn between Mr and Mrs Clark and other marriage doubles, especially Jan van Eyc’s the Arnolfini Marriage as Birtwell is pregnant in the picture. Mr and Mrs Clark both look directly at you, the chasm of the open window a tear between them: together but apart. Was Hockney able to mystically forecast their 1974 divorce? That seems like a reach, even for people that believe in horoscopes.

I know you’ve been trapped in conversation with an art-type at the pub. Someone who read semiotics at Cambridge, or even a fledgling artist in a work jacket with little splatters of paint on their cuffs. The latter speaks press release and talks in gallery prose, using 10 words when one would suffice. There’s nothing to do but nod along with their labyrinthine emissions of art speak. Artists take everything very fucking seriously. That pomp, that pretence, that plague of jargon, can be exhausting. Art is very important. The business of art can be exclusive, clutching at elitist rarity because it keeps prices up. The guest lists. The donors. The private collections. Catch art reclining in its inaccessibility, cordoned off from the non-elite, the poor.

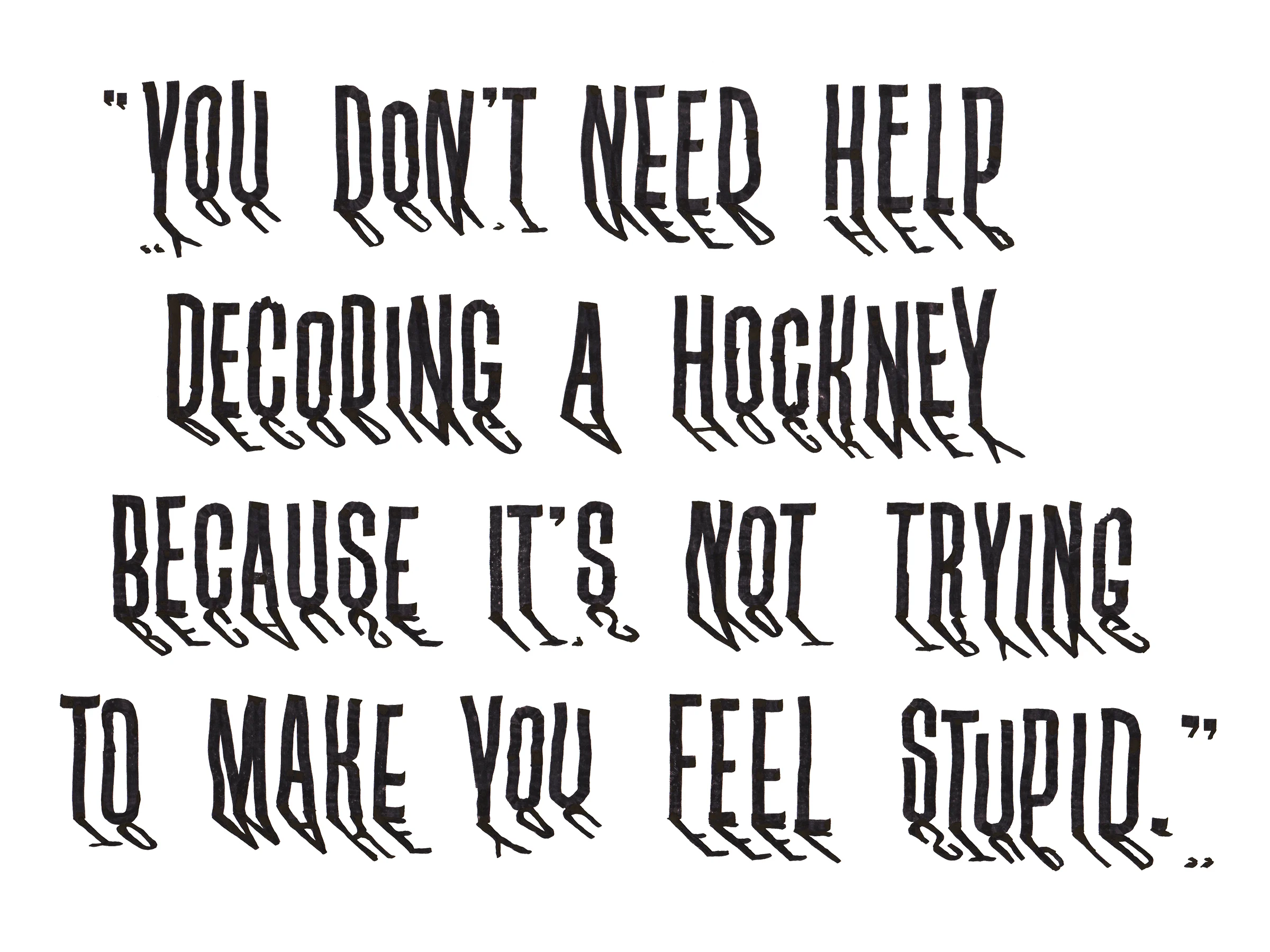

But you don’t need help decoding a Hockney because it’s not trying to make you feel stupid. It’s not a test to see if you can see beyond the form presented, an exam in sniffing out the inner turmoil or suppressed pain of the creator. Hockney is unpretentiously sincere, understanding his work without the need for a Thesaurus or three-year art degree: “I paint what I like, when I like and where I like.” The ease of viewing is itself a mastery, we lose the irritation that convoluted pretension can raise. We're not tested by Hockney artworks so much as charmed, understanding that a stack of books on a table has its own sense of contentment, sense of place. In the gallery, we’re less concerned with what does this all really mean? and more aware of how this really feels. How it feels to elevate everyday events, or be transported out of the humdrum. Hockney is the successful interloper, a country boy who’s found himself in a sunlit bohemian ideal without suffering the Bloomsbury set and their annoyingly posh voices. We’re reminded that the life we want is in front of us if we look hard enough, or at most a flight to LAX away. Hockney’s work serves as a vacation, a life lived beyond the desk job, and he paints it that we may sneak onto the plane right behind him, to ease through customs and up into the hills where a pool awaits. We’re invited into the water with the boys.

Picture the scene. It’s the mid-sixties. London is swinging but Hockey finds it drab, preferring the 24-hour cycles of east coast America which he described with trademark deadpan wit as “three times better than I thought it would be” (Would we not all love to be known for our trademark deadpan wit?) Hockney treads his own path in the States, neither part of the downtown contingent nor a Beverly Hillbilly. He paints the monied couples of the hills with their split-level mansions, the near-brutal architecture of the financial district, the brusque desert, the spindly palm trees, the pert bottoms of young men. His sea-blue eyes trace his surroundings for new subjects, finally resting on a moving target: pools.

In 1963 private pools were luxury for someone who’d only experienced municipal submergence in Britain. Now men in trunks emerge from the water to rinse and stroke their bodies in outdoor showers. For Hockney “the interest of showers is obvious: the whole body is always in view and in movement, usually gracefully, as the bather is caressing his own body.” And pools were a problem to solve: how to mimic depth on a shallow canvas. How to show fluid wetness on dry parchment. How to seize that constant shifting of a pool surface. The distorted reflections. The now-infamous splashes. Hockey described “the perversity of painting something that lasts for one second.” Early water appearances are graphic and controlled. Structured lines dance in multiple figure-eights, yellow sun highlighting cresting waves. Water illustration evolves with the painter as California soaks in. Softer. Gentler. Deeper. The pool of A Bigger Splash is flat and placid, all movement centred on the just-disappeared subject beneath the surface, small brushstrokes painstakingly replicate the motion in acrylics.

Each pool and Californian vista Hockney paints becomes emblematic of the ‘60s mood swing. No so much free love, as existence out of hiding with the emerging openness of gay life. Hockney is an artist playing with new identities in a tolerant playground. His appetite for newness satisfied in a hedonistic enclave. In California his fantasies become reality, as he skilfully skirts the fine line between biting wit and gentle titillation. The splashes are getting bigger, the ripples of Hockney spreading outwards. The pool has two figures. Nathan is swimming in Los Angeles. Jerry is diving. We’re passive observers of these ephemeral skirmishes before they evaporate, our skin salted, our swimmers damp. Pull up a lounger as the scene unfolds. I’m not sure where else I’d rather be.

Writer and Creative Director Raven Smith has been 32 for several years and lives in London with his husband and cat. The Vogue columnist examines the absurd minutiae of modern living and is quoted by many as the funniest person on Instagram, which does nothing to minimise his ego. His debut book Raven Smith's Trivial Pursuits is out now with 4th Estate.

If you liked Raven’s essay on David Hockney, he recommends you try reading Calypso by David Sedaris, Kitchen Confidential by Anthony Bourdain and On Booze by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Literally is WePresent’s slowly expanding library of written commissions by some of the best writers in the world.

The hand-drawn typography on this page was created by Guido de Boer.