On 13 March 2016, a terrorist attack shook the peaceful seaside town of Grand-Bassam in the Cote d'Ivoire. Three weeks later Joana Choumali stepped out onto the streets, intending to use her fascinating method of embroidering on to her photos to capture how its people were coping and rebuilding from the trauma. Take a look at the latest works in her ongoing series', as she speaks to writer Sharon Obuobi about her craft.

As a child, Joana Choumali fell in love with the art form of photography when her parents hired a photographer for a family portrait session. “I was fascinated by the way the photographer handled the camera, lighting and directed us – almost like a ceremony,” she says. “That connection and tacit communication with other people through photography was what interested me the most.”

Joana started practising photography in 1999 while she was studying graphic design in Casablanca, Morocco. Her biggest influences were portraiture photography, like the black and white portraits of her mother, aunts and grandparents which were reminiscent of the studio photography popular at the time as seen in works by Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keita.

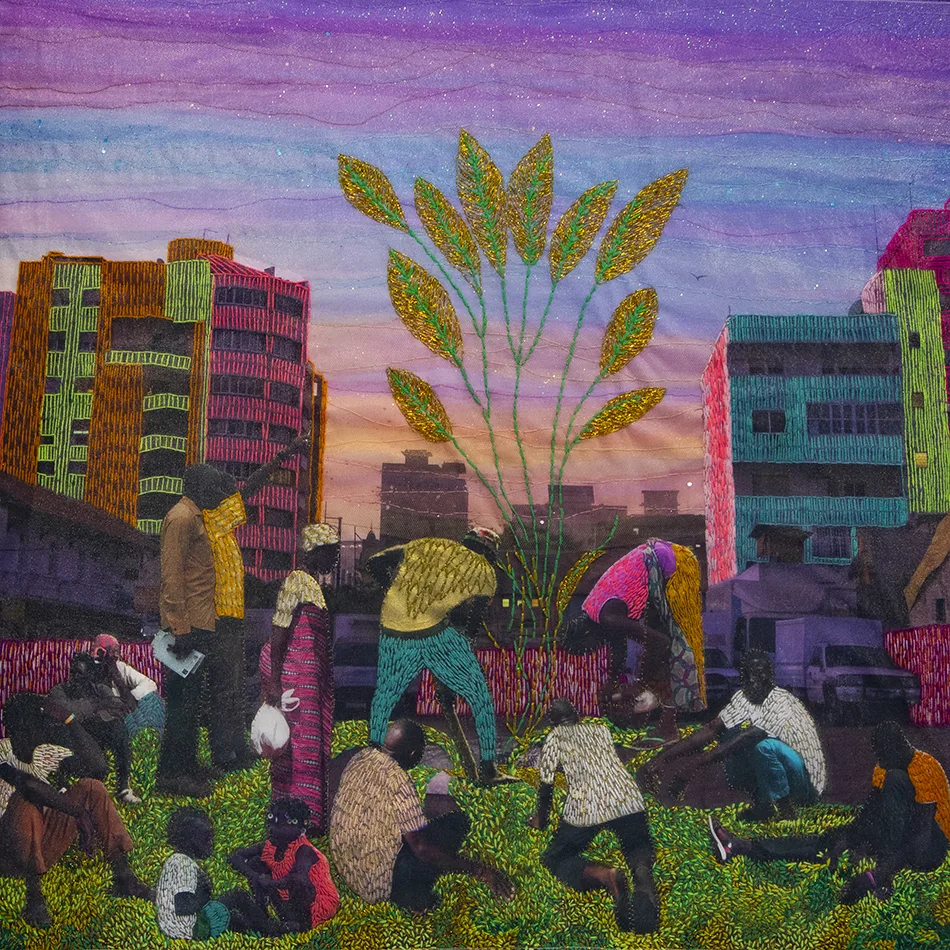

She describes her artistic process as “a subtle and particular” one. The designs and choices of colors are not planned in advance. “When I start a piece, I can’t tell how and when it will end. I set my imagination free to express itself in the photograph and reveal its message,” she says.

Growing up in the ‘80s Côte d’Ivoire, Black female artists were hard to come by in her environment. “It was less easy to project myself as an artist/photographer then,” she says. Her life experiences of being a woman in those societies with their issues and realities inform her identity and, in turn, influence what she expresses through her art. The world of Ivorian photography remains a masculine field, but she considers that an advantage, saying “...it allows me to be more comfortable with the subjects I photograph and to bond with them – especially women.”

By 2015, the deeper she delved into photography, the more she wanted to develop a more hands-on experience with her work. "I needed to stand still and formulate things that I couldn’t otherwise express with words or photography.” She chose to use embroidery as a medium for her artistic practice; the grounding action of weaving her emotions into each photograph. “It came naturally; almost instinctively.”

Joana’s 2015 series Translation marked the beginning of her transition from portrait and documentary photography to conceptual and mixed media photography. Her embroidery is self-taught and she now uses the same simple stitch in repetition, as if to repair a wound. “I remember my maternal grandmother used to stitch all day, doing patchworks with leftovers of wax fabrics and I was fascinated by her patience,” she says. “I would often ask her why she would not use her machine and she would smile, not answering. Today, I fully understand the mental effect of hand stitching. It is hard to describe, yet so obvious.”

The brightly-colored threads are the sentiments I could not express verbally.

The patchwork that she works with is called N’zassa in the Agni language of Côte d’Ivoire, referring to a fabric resulting from the arrangement of several pieces of loincloths of various patterns and colors. “N’zassa also represents the unity of the numerous cultures of my country coming together as one; different, yet complementary,” Joana explains.

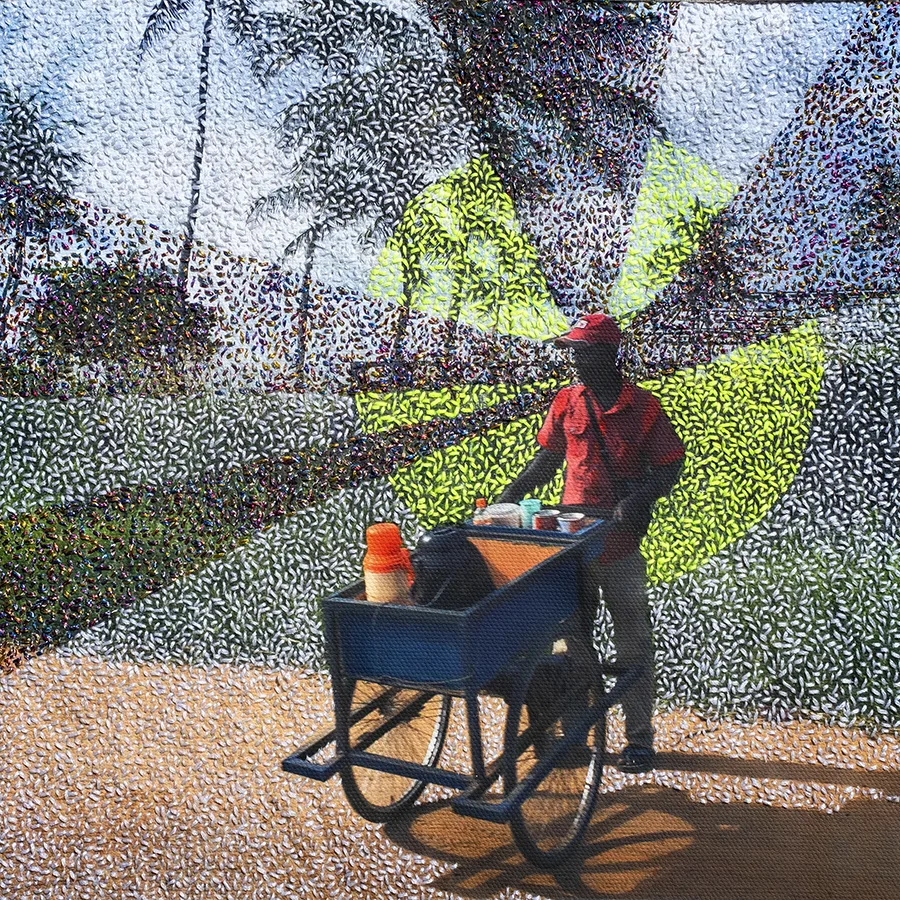

Joana uses her DSLR camera to photograph the landscape on which she hand sews human silhouettes that she photographs in the streets with her smartphone. She intertwines pictures printed on a cotton canvas with layers of sheer fabric and embroidery; each layer adding something to the landscape that recreates her thoughts and feelings while walking those streets. By hatching, erasing, cutting and pasting narratives, she redesigns her vision of a world in between dreams and reality. The different layers veiling and revealing at the same time, the feelings which coexist in her imagination.

Her combination of documentary-style photography and embroidery are two contrasting methods with respect to time. She explains that one picture could take several weeks, even months, to “download” the emotions, and she compares it to automatic scripture. But working at a slow pace can be a challenge in itself.

For Joana, the act of spending more time on the pieces forces her to explore thoughts that she would have otherwise avoided when shooting a digital photo. She describes it as a constant discovery, requiring patience and consistency, the act of embroidering being consuming, intricate and tiring.

From her body of work, we can feel her love for capturing the soul of a city, be it Abidjan, Johannesburg, Casablanca, Accra or Dakar. “I have a deep love for my city. I feel very anchored here, rooted in my country,” Joana explains. “Abidjan possesses an indefinable charm, something special that people can feel, a bit like New York. It is a place that either you love immediately or you detest. It is really about the relationship with this land; I feel like I am a part of my city. I belong to it when I walk around contemplating it and I find poetry and beauty where people usually think there is none.”

On 13 March 2016, a terrorist attack shook the peaceful seaside town of Grand-Bassam near Abidjan, the economic capital of Cote d'Ivoire. Three weeks later Joana Choumali stepped out onto its streets, intending to capture how its people were coping and rebuilding from the trauma. What she witnessed was a town determined to overcome despair with hope which she documented in her work Ça va aller. “At that time, I could see the strength of the human spirit and the power of time passing – this wonderful ability to recover from trauma,” she says.

Ça va aller features extremely intricate embroidery upon documentary-style street photography. “After the attacks, the atmosphere of the little town had changed. The energy was different; as if life was painfully running in a melancholic slow motion,” she says. In an effort to capture the subjects looking natural, she decided to shoot the pictures with her iPhone, capturing people by themselves, walking in the streets, standing or sitting alone, lost in their thoughts.

Walking in the morning for me is like walking on a white page, where anything can be printed.

To cope with her own emotions, Joana worked by embroidering over the images on printed canvas as if she were connected to the people in the photograph. “The brightly-colored threads serve as the sentiments I could not express verbally and a way to witness and acknowledge the trauma of the people of Grand-Bassam,” she says. The meditative process has become ingrained in her daily practice as a way to focus and project hope.

In November 2019, an independent jury, chaired by Sir David King, selected Joana for the Pictet Photography prize centered around the year’s theme of hope, making her the second female and first African artist to receive it. In a ceremony at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, Joana was presented with the Eighth Prix Pictet for Ça va aller. The title, which translates to “It’s going to be fine,” is a common phrase used by people in Côte d’Ivoire to casually reassure each other, even after a deeply traumatic event like the 2016 attacks.

Joana begins each day by getting in touch with her surroundings, observing landscapes, the shapes of buildings, objects, streets and people awakening and slowly revealing themselves. “I witness the energy of the continent and the changes in myself. Walking in the morning for me is like walking on a white page, where anything can be printed...I organize my process to work on the most fragile parts of the pieces in the morning when my eyes are not tired.”

The first emotion she feels is of being in a neutral, safe place where her emotions find a way to be in synchrony with the environment and the complexity of mixed and conflicting emotions coming together in her head on those early morning walks. “In the morning, the air is cooler, with a light fog which dissipates as the day breaks. By adding sheer fabrics, I recreate this particular morning light and dreamy atmosphere.”

She believes recreating the beauty of the lively African towns of Abidjan, Dakar, Casablanca or Accra, is also a way of breaking the misconception that you can only find poetry in ordered and clean places. She says: “By doing so, I have understood that what I was hoping to find on a journey abroad, I finally discovered in my own home.”

She believes recreating the beauty of the lively African towns of Abidjan, Dakar, Casablanca or Accra, is also a way of breaking the misconception that you can only find poetry in ordered and clean places. She says: “By doing so, I have understood that what I was hoping to find on a journey abroad, I finally discovered in my own home.”

Joana’s empathetic practice has helped establish herself as a voice of her times and she continues her evolution as an artist. She is currently researching a new mixed media project that’s both documentary and conceptual, involving portraiture, street photography, collage, and embroidery.

“My work allows me to connect with other human beings without having to talk. To me, that kind of connection is the most rewarding aspect of being an artist.”