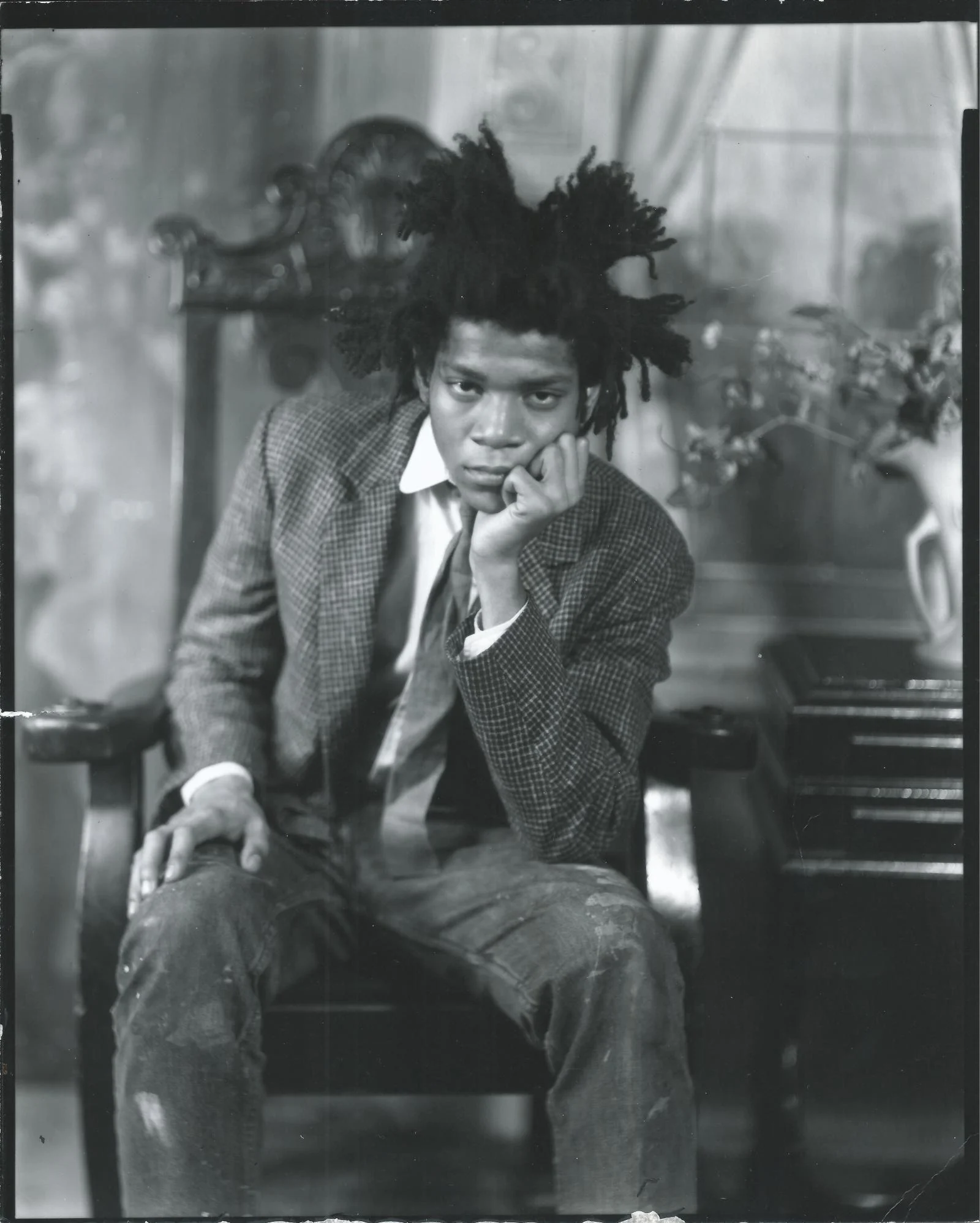

We know how much artists are inspired by other artwork or other artists, but how much does an artist’s family life and upbringing impact their creative output? In April 2022, more than 200 never-before-seen artworks, photographs, and artifacts will be exhibited in “Jean-Michel Basquiat: King Pleasure©,” a show curated by the artist’s family.

Here, writer and curator Ferren Gipson speaks to Basquiat’s sisters, Lisane Basquiat and Jeanine Heriveaux, about their brother and the family life they experienced together growing up.

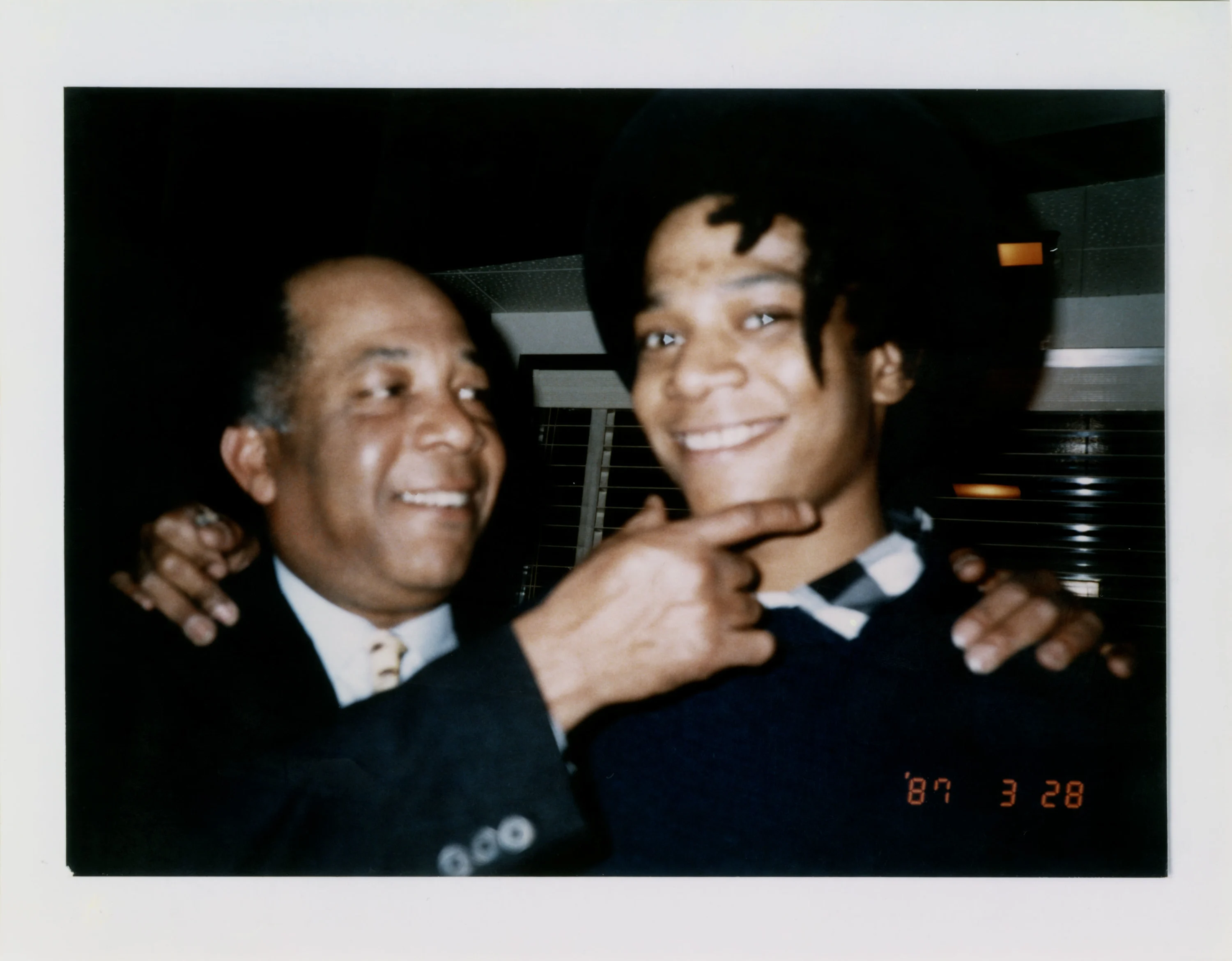

In his late teens and early twenties, Jean-Michel Basquiat made a triumphant splash onto the New York art scene—first, with his SAMO graffiti poetry in collaboration with Ali Diaz, and then with handmade postcards. He famously sold his “Stupid Games, Bad Ideas” card to Andy Warhol in 1979, but the two artists did not become friends and collaborators for another four years. Later, he stepped into the fine art arena with his attention-grabbing contributions to the group shows, “The Times Square Show” (1980) and “New York/New Wave” (1981). Off the back of these successes, he took up an artist residency at Annina Nosei Gallery at the end of 1981, which is when he began to paint on canvas. It was there that he held his first American solo exhibition in March 1982. The first person he wanted to show the exhibition was his father.

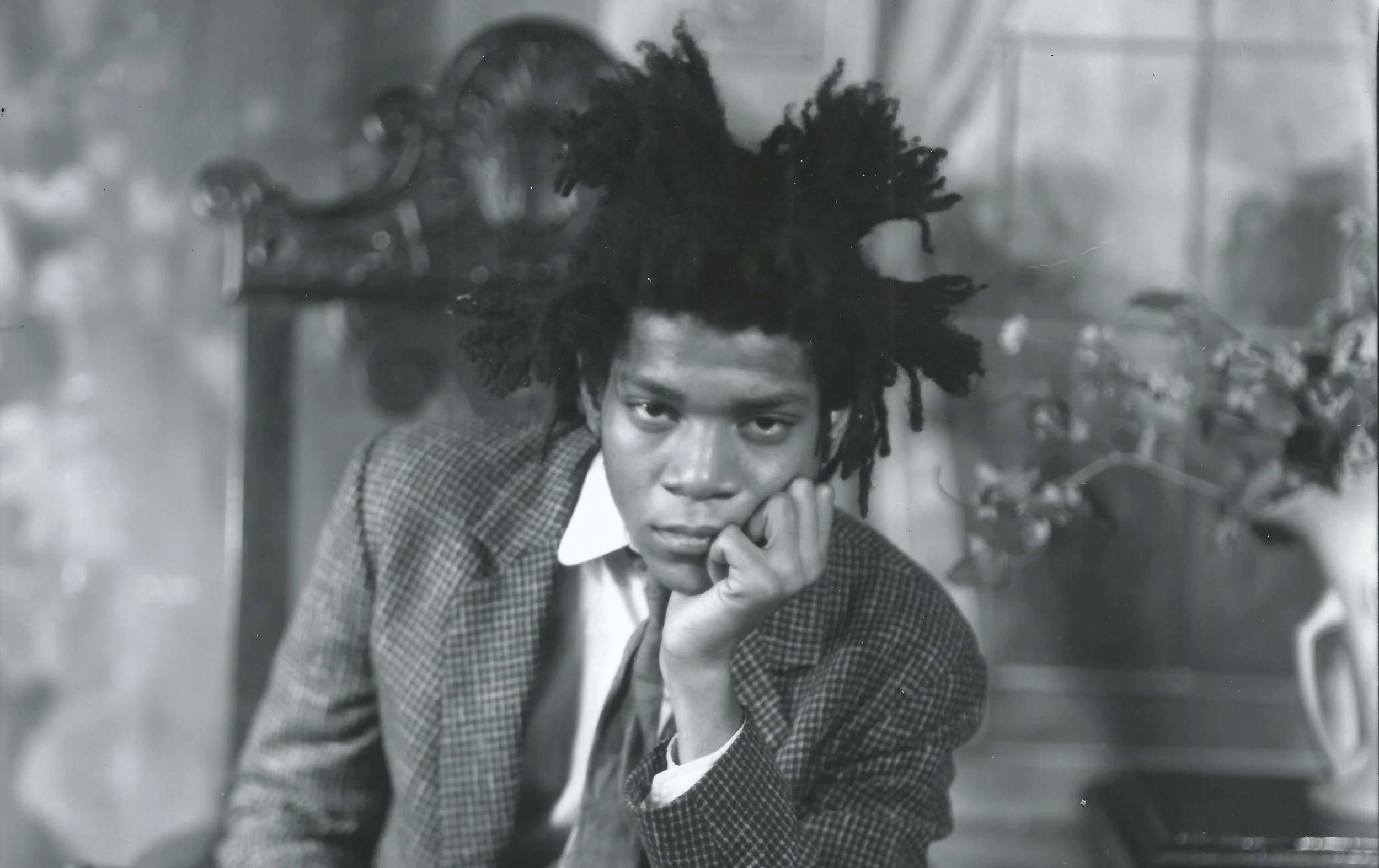

One imagines that watching a close family member skyrocket to fame as Basquiat did at a young age would be jarring, especially as his sisters, Lisane and Jeanine, describe him as being shy at times. They explain that being shy didn’t mean he lacked tenacity.

“He was incredibly determined and focused on being a famous artist—that’s what he wanted to do. It takes courage to do that, and you can be shy and still have business acumen or gather the courage to walk up and meet a person that you really want to meet,” says Lisane. “He was 18, 19, 20, and got himself into the groups and the communities that would help him. And that would give him exposure to his work. And that’s something for someone at that age to be able to do as a pioneer. There was really no precedent for what Jean-Michel did.”

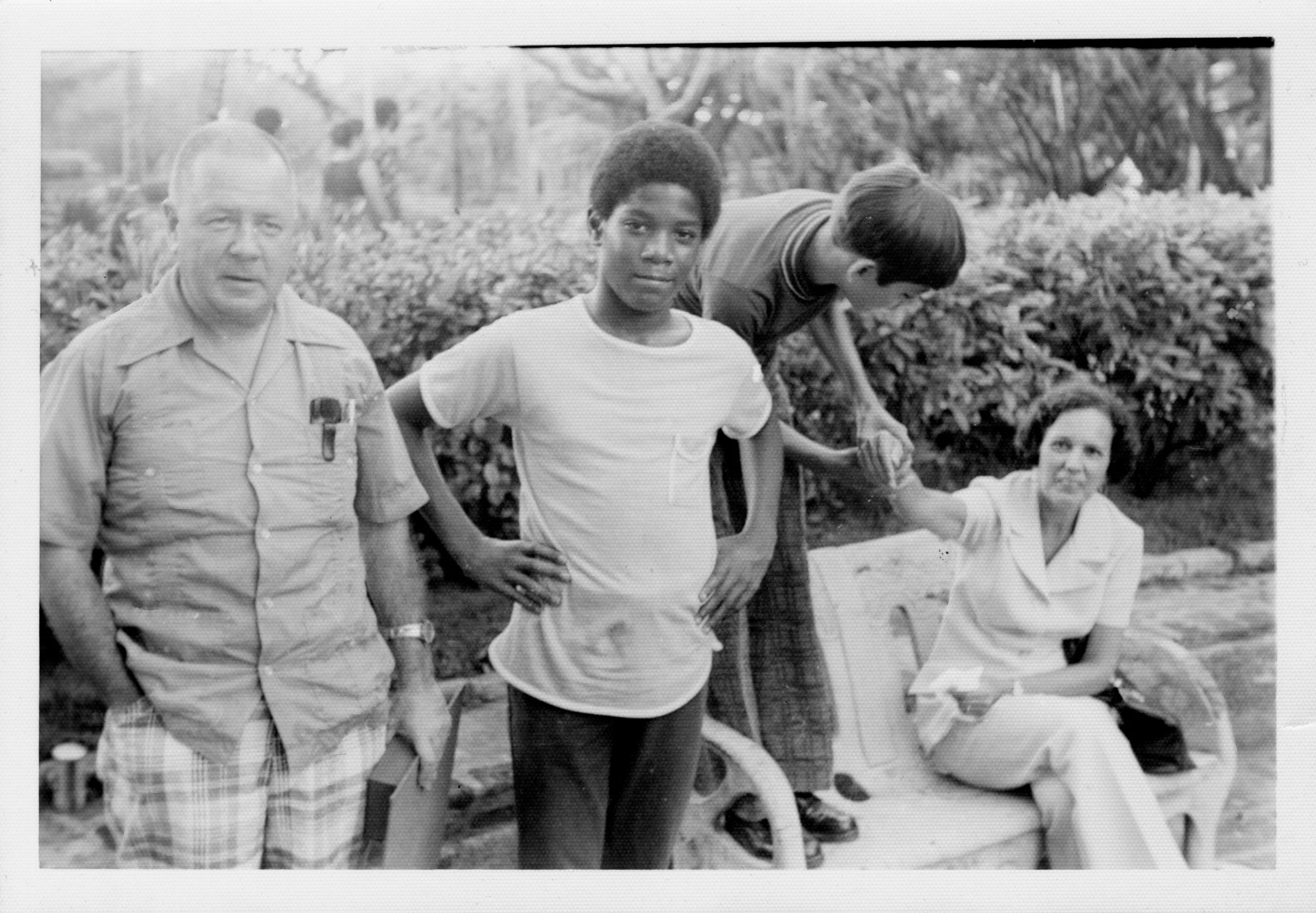

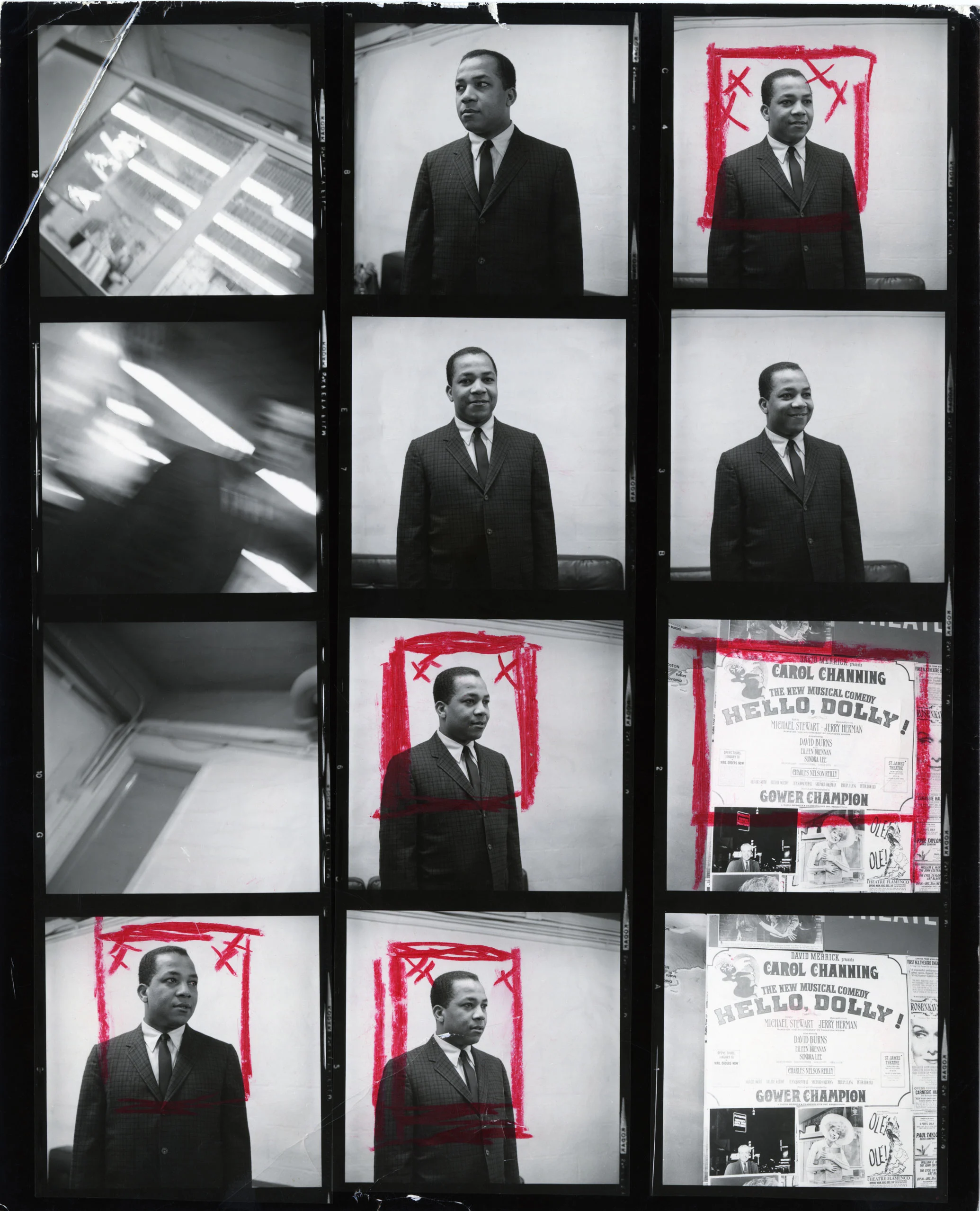

Basquiat was born in 1960 to Gerard and Matilde Basquiat in Brooklyn, New York. He was the family’s second child—their first son, Max, died before birth in 1959—and his sisters Lisane and Jeanine were born after him in 1964 and 1967, respectively. The trio were very close as children. His sisters describe a playful atmosphere where they would go outside to play with the other kids in the neighborhood, or find other creative ways to entertain themselves.

“[It was a] dynamic that a lot of families have, where the children create this little bubble of fun and fantasy and mischief,” says Lisane.

![Left to right: Lisane, Jean-Michel, and Jeanine dressed nicely for a group portrait taken at a photo studio. Lisane says, “We were super sharp. My thought about this photo is I always feel very warm [when I look at it].”](https://images.ctfassets.net/adaoj5ok2j3t/1mlSlX8Q3U7Yeq0tnqU2sT/33691fcac0475a9d1c7ddb8bed9180cd/basquiat-wepresent-Copy-of-J-MB028_-Estate-of-Jean-Michel-Basquiat.jpg?fm=webp&w=3000&q=75)

He was incredibly determined and focused on being a famous artist—that’s what he wanted to do.

The family first lived in the Flatbush neighborhood in Brooklyn before later moving to Boerum Hill in 1972. At the time, many families were moving to that area because they believed in its potential to become a diverse and beautiful community. By the time the Basquiat family arrived, the parents were divorced, and the children were living with their father. A job promotion in 1974 would take Gerard and the kids to live in Puerto Rico for a couple of years, but they returned to live in Brooklyn in 1976.

“I remember when we lived in Flatbush on 35th Street. We would play with the kids outside,” says Lisane. “We played the typical things that kids in Brooklyn played, like freeze tag and hide and go seek.”

“You had to really get creative in the games that you played, whether they were indoor or outdoors,” says Jeanine. “There were no play dates, it was a completely different time. The three of us were really creative in keeping ourselves busy.”

When they were little, their mother Matilde entertained the kids with excursions to museums. She first began to take Basquiat on trips to the Brooklyn Museum and the MoMA in 1965, after he showed an interest in drawing. Once Lisane and Jeanine were born, Matilde would take all three of them to museums, the botanical gardens, and other cultural hotspots. Gerard contributed by coming up with traditions they could all be a part of, in particular taking the entire family apple picking in the autumn. They’d gather enough to last them for months, and Gerard made sure the holiday season was a memorable, special time for all of them. “Our father was always very elaborate about Christmas,” says Lisane. “On Christmas Eve he would come in, and we would have gifts under the tree that were all colored differently. So, it might be that my gifts are silver, Jean-Michel’s are gold, and Jeanine’s are blue. And he would color-code them, so we’d know which gifts were which.”

Lisane and Jeanine also describe their father as a joker and say it is from him that Basquiat inherited his mischievous, prankster temperament. It wasn’t uncommon for the sisters to discover that he had left some practical joke in their beds to scare them. While his sisters describe him as having a playful, cheeky manner, they say he was also pensive and intentional in his actions.

“He was very witty and sharp with his words,” says Jeanine. “He really had intent and purpose in the things that he was saying. He was very intentional, I would say, from a child.”

Meanwhile, in Steven Hager’s book, “Art After Midnight: The East Village Scene,” Basquiat is quoted saying that “the art came from” his mother. Perhaps this is a reference to times when Matilde would sit and draw with him as a child, the frequent museum visits she organized, or to her stylish sensibility that is so evident in the way she dressed herself and the children.

Matilde was also pivotal to her son’s early artistic education as it was her who introduced Basquiat to the book “Gray’s Anatomy,” gifting it to him after he was hit by a car and hospitalized at age eight. The book would become a recurring theme in his life—he later named his first band Gray and was often inspired by the publication’s anatomical texts and drawings for his own paintings.

There was really no precedent for what Jean-Michel did.

“Everything was source material for him,” Lisane says. “He [might] walk across the room and see a paperclip and maybe that would inspire him, inspire something.”

His extraordinary ability to see the artistic potential in an idea or object speaks to Basquiat’s creativity and keen intellect. Some critics frustrated themselves trying to draw connections between the elements of his work, unable to fully decipher his distinct process and methods. When Basquiat painted, he was known to keep piles of open books around him while music played in the background. He read all manner of texts and was deeply curious. The books scattered around his studio could range in topic from poetry to art history.

The music that soundtracked his painting was also varied, ranging from classical music to his favorite genre, bebop. And as if that wasn’t stimulation enough, he would sometimes have the television on as well. This confluent mixture of media was a source of inspiration that would permeate his thoughts as he worked, and elements would sometimes find their way onto the canvas as words or images.

Jean-Michel was first and foremost, a human being.

During a filmed interview with art historian Marc H. Miller in 1983, Basquiat talks through elements of his painting, “Notary,” which depicts images of a Roman belt buckle, anatomical figures, fleas, and a mixture of other words and images. Marc appears flummoxed as he tries to understand why each element was included and how they all connect to each other, but Basquiat smiles as he explains that he included things he liked. His face lights up as he shares fascinating nuggets of information tied to the elements of the work. When Marc points to the word “SALT” to ask what it meant, Basquiat states that salt was a currency in ancient Rome. When they come to a section showing a circular design with lines, he explains that it’s a depiction of Pluto based on the first drawing of the moon by Galileo. He casually drops fascinating glimpses into humanity that are completely lost on the interviewer. Basquiat would pluck out the information or ideas that struck him most and display them back to the world, showing what he’d discovered but communicating it in his own unique language.

This spirit of show-and-tell—perhaps more appropriately, it could be called learn-and-show—is a trait that he exhibited as a child and carried with him into adulthood. He showed ideas in his work, yes, but on a more personal level, it was important to him to share what he was experiencing with his family.

For example, he learned about fondue,” says Lisane. “At the time we didn’t know anything about fondue—we loved cheese but didn’t know about fondue—and he made fondue and showed it to us.”

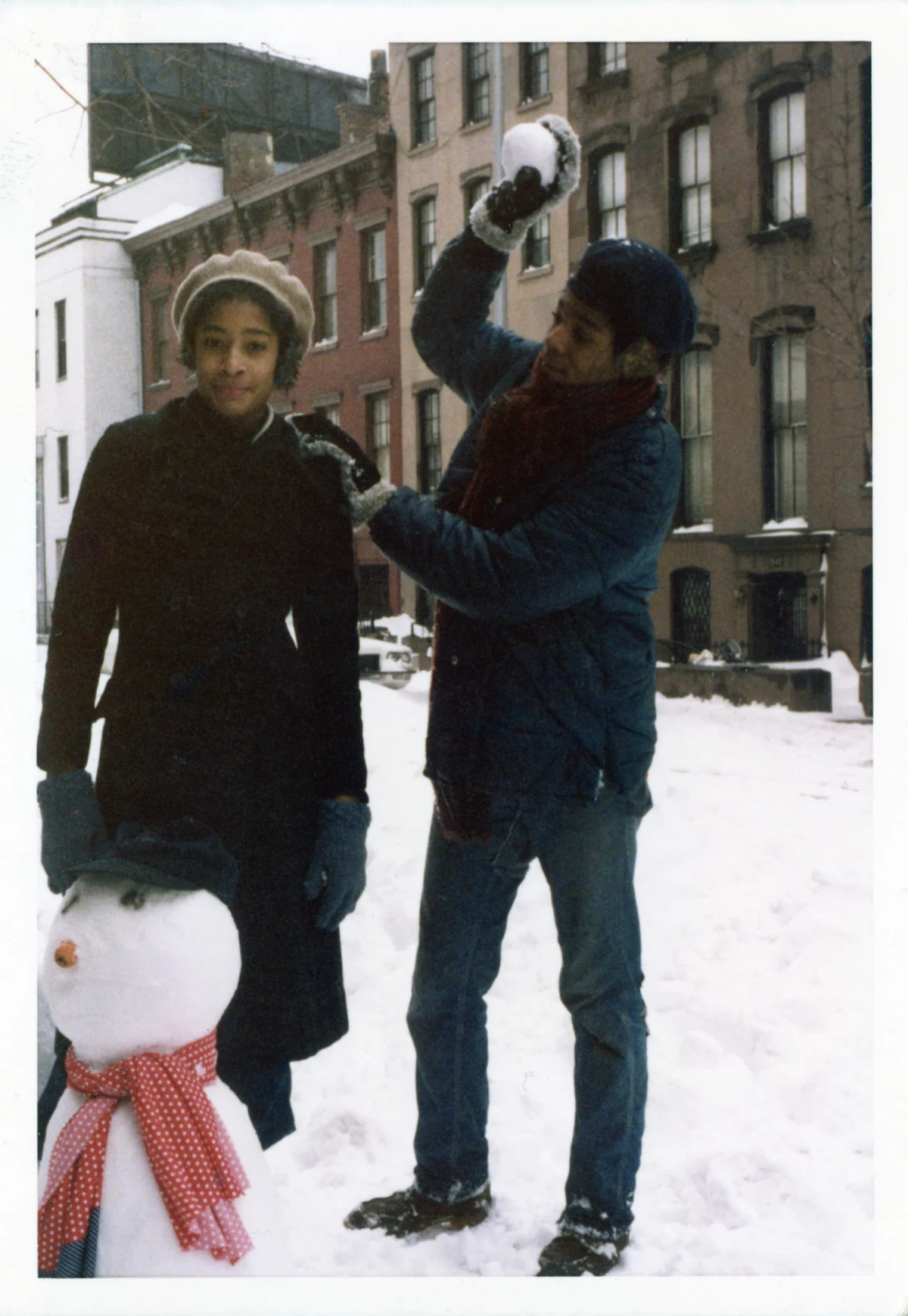

In considering his spirit of showing and sharing, we begin to understand why it was so important to Basquiat to show his father his exhibitions, or introduce him to his mentor Andy Warhol. It also offers a touching perspective on him inviting his family to vacation with him on a ranch in Hawaii in 1984, which he said was one of his favorite places he’d ever visited.

Throughout Basquiat’s prolific career, he created works that challenged societal structures around race and class, and called long-standing hierarchies into question. He showed Black men as kings, he drew inspiration from the art and histories of cultures around the world, and he platformed concerns around critical issues, like police brutality, through his fine art expression—by juxtaposing concepts across popular culture, politics, and art, he invited conversations around how societies interrelate and what we value.

“One of the things about Jean-Michel that’s so incredible and hard to really explain is that 33 years after his passing, [he] is just as relevant today as he was 33 years ago,” says Lisane.

Lisane and Jeanine took over their brother’s estate in 2013 (their father Gerard had managed it up until his passing that year) and, along with their stepmother, Nora Fitzpatrick, are now presenting the “King Pleasure” exhibition at Starrett Lehigh, featuring more than 200 rare and unseen works, photographs, and artifacts. The family are taking a personal approach to exhibiting his work, naming the show after one of Basquiat’s paintings, which, in turn, is named after the jazz vocalist whose hit, “Moody’s Mood for Love,” was a much-loved tune of their father.

We wanted it to be solely from the perspective of our family.

“We wanted it to be solely from the perspective of our family,” says Jeanine. “We have really done our job in making sure that those that come to see it feel the emotion that we have put into every part of this exhibition, from the catalog to every room that [they] will step into. We are giving them a personal narrative of him.”

“Jean-Michel was first and foremost, a human being,” says Lisane. “A human being who was courageous, brave enough, gifted enough to live the dream, to share his gifts with the world.”

Creating the show has given the sisters an opportunity to take a healing deep dive into their personal history and to not only reflect on Basquiat’s artistic legacy, but on the touching personal impact he had on the lives of his family. “In the beginning I felt like, ‘That’s my brother!’ And now, I’m in awe of how profound Jean-Michel has been in so many ways,” Lisane says. “Even, with him being one of the first, as a Black man, to just be like, ‘Yeah, I have a crown. I’m a king.’” It is the family’s hope that people will come to better understand and appreciate their brother on a human level. He is a titan of art, yes. But a human first.