Competitions of all kinds happen all over the world each year. Some—namely sporting events—take up a lot of space, whereas others, such as the International Aquatic Plants Layout Contest, are slightly more unheard of. That said, to those that enter, competing in this creative championship means the world.

Writer Kenji Hall meets some of the people who dedicate their lives to creating enormous, magnificent living interiors for fish tanks in order to take the crown as the winner of this curiously bewitching, one-of-a-kind competition.

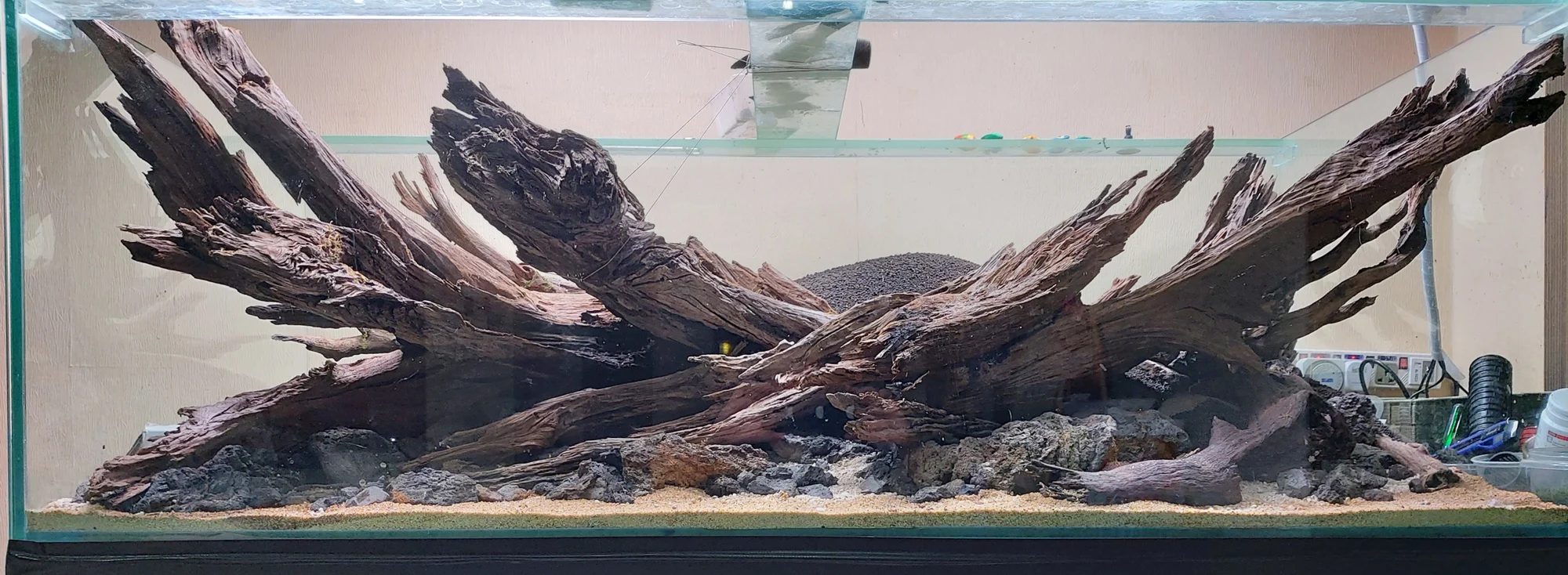

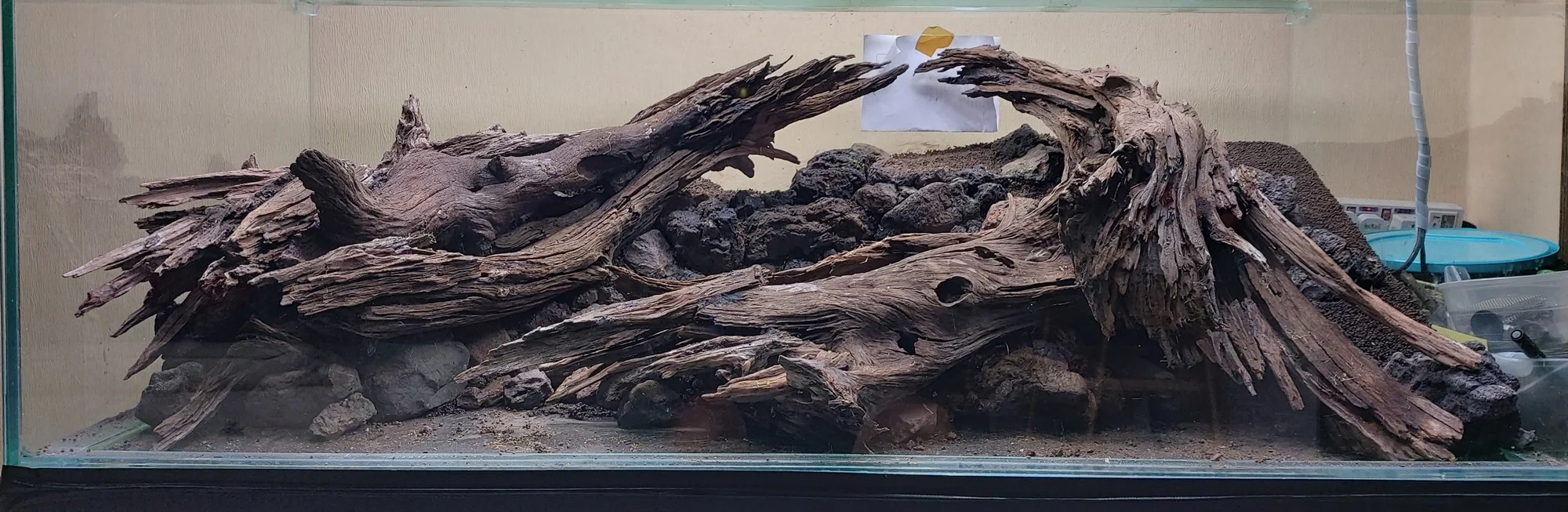

Sometime before the end of May 2022, Josh Sim will set up a camera on a tripod, shut off the lights, and convert his living room into a makeshift photo studio. The subject of the shoot: a 300-liter fish tank with a thriving freshwater ecosystem of plants and mosses, iridescent fish, tiny snails, and algae-chomping shrimp. Ideally, the vegetation will appear robust and voluminous yet not too overgrown that it detracts from the interplay of light and shadows on the driftwood-and-stone backdrop.

Sim only wants one good image. If he’s lucky, it might take him a couple of hours to finish. But it’s just as likely to drag on for days. He could end up with 900 photos—it’s happened before. Everything depends “on the cooperation of the fish,” according to Sim. He needs them to position themselves so they accentuate the watery world they inhabit, so their small bodies add to the illusion of something too grand—say, a vine-tangled, old-growth forest in Congo—to have been made by Sim at his home in Johor Bahru, Malaysia.

In recent years, the growth of nature aquariums has spawned a few problems. The worst: contest rule-breakers.

By then, Sim, a 47-year-old chemical engineer at a German multinational, will have spent the equivalent of several thousand euros and more than half the year preparing his 1.2-meter-long tank for the decisive moment. “I love photography, but I hate taking photos of my aquarium. It’s the most stressful part of this hobby,” he says.

Sim is one of the world’s most decorated creators of nature aquariums. He belongs to a global community of hobbyists who design and build elaborate underwater habitats so chemically-balanced and teeming with microorganisms that even the fish might be fooled into believing that their surroundings are the work of evolutionary forces. Mixing aquaculture, Japanese gardening, chemistry, and photography, these aquarium enthusiasts make art that is an homage to the sublime unpredictability of the living world. Some have opened stores or gone into business making high-end aquariums worth tens of thousands of euros for businesses and wealthy families from Budapest to Hong Kong.

Aquascapers are a motley bunch. They’re fish people. They’re aquatic plant fanatics. They’re architects and painters and engineers and marketers. They’re obsessives who spend weeks on a concept and months on the execution: arranging and rearranging and gluing stones and pieces of wood, tying bits of moss into place, using tweezers to insert plants into the soil, waiting for stems and leaves to sprout and selecting a few fish from among hundreds of different types to bring the tank to life. They live for the friendly rivalry and the camaraderie of their tribe.

For the members of this tribe, nothing is more important than the International Aquatic Plants Layout Contest (IAPLC) in Japan. It’s the World Cup of planted aquariums, the oldest and most prestigious of what has become a global circuit of competitions. For many contestants, taking home the IAPLC purse—¥1 million (€7,600) for the best in show, ¥10,000 to ¥300,000 (€77 to €2,300) for the others—is secondary to having the Grand Prize title bestowed on their work. Sim has won the IAPLC’s top award twice, a feat that only one other aquascaper has ever accomplished in the contest’s 21-year history.

The IAPLC is the brainchild of Takashi Amano, a Japanese former pro keirin track-cyclist-turned-photographer-turned-aquarist. Beginning in the mid-1970s, Amano trekked deep into the tropical forests of Brazil, Gabon, and Borneo, in search of rivers to dive into and pristine places to photograph with a large-format film camera. Amano’s trips inspired him to begin building aquariums that were a window into the natural world: not just to keep fish but also to grow the plants of their habitat. By 1982, Amano had launched Aqua Design Amano (ADA) in Niigata, northeastern Japan, to cater to people like himself. He is credited with elevating aquariums to a high art by inventing new tools—soil, scissors, lamps, and carbon-dioxide pumps—and introducing Japanese gardening techniques.

In 2015, Amano completed his largest commission for Portugal’s Oceanário de Lisboa. Filled with 160 tons of water, the 40-meter-long tank has 20 tons of volcanic stones, 46 plant species and 10,000 tropical fish. He later discussed the work as a kind of exploration. “The basic philosophy of all my creations is to understand nature and be able to recreate its power,” the 61-year-old told an interviewer. It was Amano’s final commission. He died a few months later.

The IAPLC has grown from 557 entries representing 19 countries in 2001. Last year’s contest drew a record 2,617 submissions from 84 countries. Only the top 127 entries are ranked and rated by a panel of 10 judges. (ADA whittles the field for the judges, who see each aquarium only as a photograph, a title, and dimensions). The health and vibrancy of the plants and fish—how they benefit from each other in a balanced habitat—counts the most. Veteran judges have enough experience looking after their own schools of Siamese algae-eaters, harlequin rasboras, and cardinal tetra fish to recognize the optimal colors of each species and how they should look at their most vigorous. Technique, originality, and composition also matter. The judges want to see that the Christmas moss and spade-shaped basil-like Staurogyne repens and slender Blyxa japonica grass have flourished on their own for months, not just been added for a photo shoot.

With a single image, skilled aquarists can convey a lot, says Tsuyoshi Oiwa, who heads the IAPLC steering committee. By varying the heights and color of plants and selecting only small fish, they can make the tank seem vast and create a sense of movement. By using oxygen bubble-releasing plants, they can add a vibrancy to the vegetation. “You have to understand the connection between organisms, ecology, the chemical properties of water, and landscape design aesthetics. And you really need to love looking after living creatures because long-term tank maintenance—trimming the plants, monitoring water chemistry, keeping a fish-plant equilibrium—is hard work,” Oiwa says.

[Takashi Amano] likened aquariums to the fish being on a stage. The good ones are healthy ecosystems and also exquisite works of art.

Ranking art is subjective, and Amano was always careful not to criticize imaginative work of any kind, says Shogo Yamaguchi, editor-in-chief of Japanese fish and aquarium magazine Aqua Life and an IAPLC judge. One year, a Croatian contestant made the top 10 with a desert-like scene, complete with low-lying succulents and cactus lookalikes. Other contestants have made waterfall scenes and the Alps mountain range, the fish swimming by as if they were migrating birds. Rarely do the judges agree on a best-in-show, but they approach their task with an understanding of Amano’s thoughts about nature aquariums. “Amano-san wanted people to be moved by the beauty of aquariums,” says Yamaguchi, who has covered nearly every contest. “He likened aquariums to the fish being on a stage. The good ones are healthy ecosystems and also exquisite works of art.”

In recent years, the growth of nature aquariums has spawned a few problems. The worst: contest rule-breakers. The IAPLC disqualifies contestants who post their aquariums on social media before the judging, submit multiple entries under aliases or work that’s been sent to other contests, or touch up their digital images in any way. “We have had to spend a lot more time policing this kind of thing,” says IAPLC’s Oiwa. A few years ago, the IAPLC also launched a Green Manner campaign to discourage hobbyists from dumping the contents of their tanks—freshwater flora and fauna that might be indigenous to some other corner of the planet—into local waterways.

The basic philosophy of all my creations is to understand nature and be able to recreate its power.

Every aquascaping enthusiast has a story to tell about encountering Amano and his aquariums for the first time. Occasionally, it was life-altering. André Longarço was working in architecture in São Paulo in 1993 when he bought Amano’s photography book, Garasu no Naka no Daishizen (The Natural World Inside of Glass), on eBay. The day it arrived in the mail, Longarço—now an IAPLC judge and the host of a popular aquarium show on Brazilian TV—called his friend, Luis Carlos “Luca” Galarraga, an architect. “I went to his house and spent the entire afternoon reading and just being amazed by Mr. Amano’s work,” says Galarraga. “I was 27 years old. When I saw the book I felt that I needed to know how to make these amazing aquariums that we saw in his book.” In 2003, Longarço and Galarraga quit their jobs to open Aquabase Aquapaisagismo, Brazil’s first nature aquarium shop. Years later, when Galarraga met Amano in Niigata, Amano hosted a seminar and gave him tips. “He told us that you must identify the most powerful site of your layout. In this place, you need to use taller plants, red plants, to increase the effect. This was the beginning of a style that nowadays everyone recognizes as Brazilian,” Galarraga says.

The reverence towards Amano among aquascapers can make him seem a cult figure. Even now, the hobby’s traditionalists are loyal to Amano’s legacy. They stick to the plants, fish, and techniques that he pioneered. Progressives strain to break away from the orthodoxy but they, too, claim to channel Amano by putting originality above everything else. In either camp, it’s common to hear people pepper their speech with Japanese: iwagumi (rock arrangement); ryuboku (driftwood scenes); wabi-sabi (the effect of time, and the beauty that it draws out, on living and inanimate objects).

The hobby has long outgrown its Japanese roots. What binds the community now, says Steven Chong, is a shared appreciation for nature. Chong, a Hawaiian native and US citizen who lives in Tokyo, attributes his own meteoric IAPLC surge from 525th place in 2017 to runner-up in 2020 to the help of his mentors in Tokyo but also to an eye-opening stroll through Oirase Gorge, one of Japan’s most picturesque valleys. “Even when I am just dropping my daughter off at the school bus, I’m paying attention, I’m seeing and also trying to feel, to gain a natural sense of how plants grow and how they form in different shapes. It’s a continued dedication,” says Chong, a marketing manager at IBM Japan, who rises every day at 4 a.m. and devotes two hours to his craft before his young family wakes up.

Everything depends ‘on the cooperation of the fish.

Over the years, improvements in techniques have led to more complex layouts and dioramas. Contestants have been known to use 3D CAD software to map out every detail. In 2012, Macau’s Zhang Jiang Feng won the Grand Prize by recreating an Amazon rainforest. Two years later, French aquarist Grégoire Wolinski’s winning entry featured an imposing rock canyon. The top-ranked tank in 2021, by Yoyo Prayogi from Indonesia, had gnarled, moss-coated trunks of ancient-looking trees. When Sim won his second Grand Prize, in 2019, he arranged pieces of driftwood in his aquarium to resemble the eroded trees that he’d spotted lying on a riverbank in a Malaysian forest in the dry season. “I tried to imagine how the fallen trees would look during the rainy season when the rivers were flooded...how moss would grow on the wood underwater and how the shadow from the huge tree would provide hiding places for the fish,” he said.

In one of Amano’s last interviews, after completing the aquarium at Portugal’s Oceanário de Lisboa, he explained how aquariums might serve a higher purpose. “Nowadays, our planet is facing destruction. Nature is in decline. From what I’m seeing, freshwater ecosystems are under the greatest threat,” he said. “In the Amazon and the rivers of west Africa and Borneo, pollution is leading to the disappearance of freshwater plants. So I wanted to convey a message that 50 years ago, 100 years ago, the underwater world was this healthy, abundant habitat. And by showing that, I wanted the public to better understand the mindset of protecting nature.”