Model Village — How Michel and Olivier Gondry made a music video for IDLES

How Michel and Olivier Gondry made a music video for IDLES

IDLES’ Joe Talbot always dreamed of working with Michel Gondry. This year, that dream came true, when Michel Gondry and his brother Olivier agreed to come together (virtually) in lockdown to make an animated video for the band’s new song, Model Village. Liv Siddall speaks to the three of them about the creative, collaborative process of making this truly spectacular, WePresent produced animation.

Do you remember the music video for Star Guitarby the Chemical Brothers?

It tends to come up in conversation when people discuss their favourite music videos. The concept was simple: a camera is fixed on the view through a window of a moving train passing through an industrial region of Europe. It triggers the sensation of a quiet moment alone, in transit, perhaps with headphones on, watching the world fly past. In the video it soon becomes apparent that each thing that rushes past – pylons, trees, telegraph poles, wires, buildings – corresponds to beats in the track. It's almost unbelievable that Michel Gondry and his brother Olivier created it together in 2003 using actual footage collected on actual train journeys, and with minimal editing tools. In the pamphlet inside the DVD of his music videos released the same year, Michel wrote of Star Guitar: "My brother and I were working really hard to not have it look clearly like either CGI or video and really mixed up both techniques to create something different.”

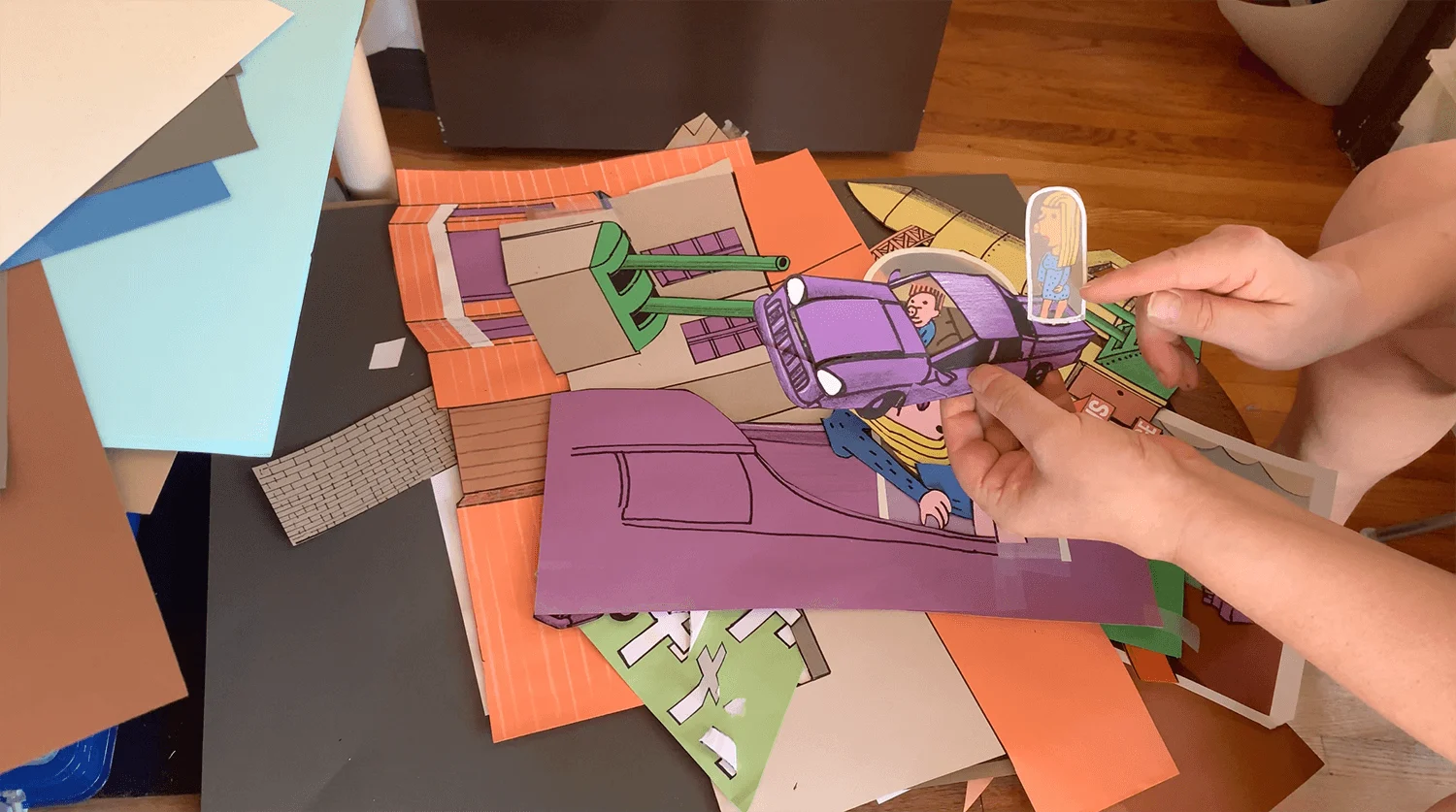

17 years later, the brothers are working together on another music video, this time for a track called Model Village by UK band IDLES. Camera and post-production technology has changed a lot in 17 years. The way Michel and Olivier work, has not. For weeks, Michel has been holed up in his studio in LA, cutting out bits of paper into characters and shapes, and arranging them on his desktop and filming it from above on his iPhone, before sending them over to Olivier in Paris who takes the collages and uses software he has adapted or created to bring it to life. “Olivier and I work with completely opposite techniques,” says Michel. “That's why we were excited to do this video because I work with the primitive system which is cutting paper, moving paper under the lens frame by frame. Olivier turns all that in between morphing, warping and CGI.”

They’re funny, these two. Very close. Olivier tells me a story about how he had a scary memory of being chased by some men in the street, and only years later after telling the story many times, he heard Michel telling it and realised it was not his memory, but his brother’s. They first “collaborated” over Lego as young kids, but then officially at a party when they were teenagers in 1982, programming 50 spotlights (before LEDs) to flash in time with music.

“You have two type of people: some who say, ‘Yes, I do it, no problem,’ and they don't do it. Olivier generally says no, and then he does it anyway,” says Michel. “It's an attitude and reliability. He doesn't stifle people. And when he decides he's going to step on the creativity, he is going to say exactly what he thinks. And in terms of creativity, he could use a computer upside down, basically.” And what does Olivier think about working with Michel? “He doesn't have much limitation with imagination. He's very good at having the image in his mind and delivering it at the end,” says Olivier. “He actually said to me that what he loves on the job is when it's as close as possible at the end to what he imagined at the start, I was surprised by that because my process is different. But I think what's most surprising with Michel is the surprises. I think that’s been the way since the very beginning. His imagination is always going somewhere else.”

Michel and Olivier bear all the hallmarks of siblings with a symbiotic creative relationship. I ask Michel if he understands Olivier’s technological skills, he says a little, but that his programmer father did not pass that information down to him for some reason, only his brother. When I asked Olivier if he understands Michel’s methods, he replied: “It’s not exactly hard to understand cut-out paper…”

Meanwhile, Joe Talbot, the IDLES frontman, is driving home down the M4 from Wales to Bristol after practising with the rest of the band. In the last three years, IDLES have become one of the most popular bands in the UK: selling out shows, being nominated for a Mercury award and playing a Glastonbury set that went down in history as one of the festival’s best ever performances. Joe is 36, making him about a decade older than most other up and coming bands and artists in the musical world they reside in. With that comes a particular flavor of wisdom not always offered up by their contemporaries. Having been around for longer, Joe has experienced more. IDLES are not here just to stand around looking cool, spark feelings of nostalgia or fit in, they’re here, gratefully, to make songs that truly change how we are in the world, how we treat one another, how we express emotion, how we deal with things we’re ashamed of. He talks openly in interviews and in his lyrics about the loss of his daughter, his mother, addiction, migration policies, corruption, racial prejudice, sexism, male vulnerability. On stage, he’s a man on a mission with no time to lose: he needs to use this opportunity to say something very good, and very loud. Time is of the essence, they’ve got a lot to be getting on with.

Growing up, Joe’s visual diet was watching at least one film per-day with a hefty portion of music videos on the side. Like most people, his first encounter with Michel Gondry was the award winning video for The White Stripes’ Fell In Love With a Girl. Michel directed the video, and Olivier was the visual effects supervisor. Michel then went on to release his first feature film, Eternal Sunshine of a Spotless Mind. It blew Joe – then studying film – away. “The effect of what he did without CGI is huge. It speaks of meticulous work. My grandad was an engineer and I just love that kind of brain that just forges things from their imagination and makes them function,” says Joe. “Gondry’s challenging himself in different ways with every project. He’s saying, ‘how do I use my imagination and pragmatics and engineering to make it happen without using computers?’ And I just think it is a really beautiful thing that he's managed to create. It’s like a Gondry universe.”

It’s always been a dream of Joe’s to work with Michel, let alone Michel and Olivier combined. For a long time, Joe has been directing or creating videos for his songs. In June, during lockdown, he released a video for a track called Grounds from the new album. “When COVID-19 hit, we thought, ‘what kind of videos can we make for each song that uses the disadvantage of isolation to our advantage?” he said. “Instead of seeing it as, ‘Oh, we're fucked now.’" Joe enlisted the help of Rob French and JonesMillbank, who strapped a camera to a car and drove around a deserted Bristol at sunrise, chasing an actor who eventually turns out to be Joe in a balaclava. “Not being able to afford a green screen doesn't mean you can't make visually stunning things, as Gondry has proved time and time again,” Joe says. “It's always going to be part of my language, because I love film and art as much as I love music.”

Joe’s love for, and understanding of DIY filmmaking is directly inspired by Michel’s attitude to the benefits and beauty of imperfection. Michel’s 1997 video for Around the World by Daft Punk is one of the most famous examples of choreography ever filmed, but is renowned for the magic of its human charm over its precision. By showing us something simple and not technologically complex, it communicates to you that you could do it too.

“The thing about art and imagination is you don't need anything to create. A play can be just a stage, and a stage can be just your bedroom. You can use an iPhone to make a play. You don't even need an iPhone. You can write,” says Joe. “Creative thinking is the most freeing tool you'll ever have. If you were suddenly in prison for 25 years, that's the first thing you go to to feel free, is your imagination, creative thinking. Now there aren’t huge budgets in music videos. it’s like: ‘what can I do that's interesting to me, with what I have on my person now?’

With Michel living and working in LA and Olivier based in Paris, working on a DIY music video with substantially less money behind it than, say, an ad campaign, has its drawbacks. The time difference, for one, and the fact there’s no big team to help do the nitty gritty stuff, and, of course, the budget. That said, a project like this can be a welcome break for the two of them, as less budget and less people equals more freedom. “The smaller the budget is, the more I work,” Michel says, “And this budget is super small, so we work very hard on it.” He says working on a big commercial project can almost feel like a holiday because there’s so many people doing everything for you. A music video is different. “When I’m working on an advertisement I don't put as much of much of my opinion into it.”

One of the reasons Michel’s videos move us and stay with us is because working with Michel and Olivier is a dream come true for an artist, and you feel that beaming through the screen when you watch the video. Not many directors could persuade a band like The Foo Fighters to dress up as teens in a slasher movie, or convince Meg and Jack White to spend 16 days creating a complex stop motion film in downtown New York at the height of their fame. But it goes both ways: Michel feeds off that excitement too. “It's a question of respect as well. I feel appreciated. You can feel the excitement of the artist working with us and that's stimulating, and we feel that our work will make the person happy,” he explains. “I mean, I'm a bit like that. That's why I work with Björk so often because she gives me 100% trust. And the more trust you have, the more pressure when you produce it.”

Creative thinking is the most freeing tool you’ll ever have.

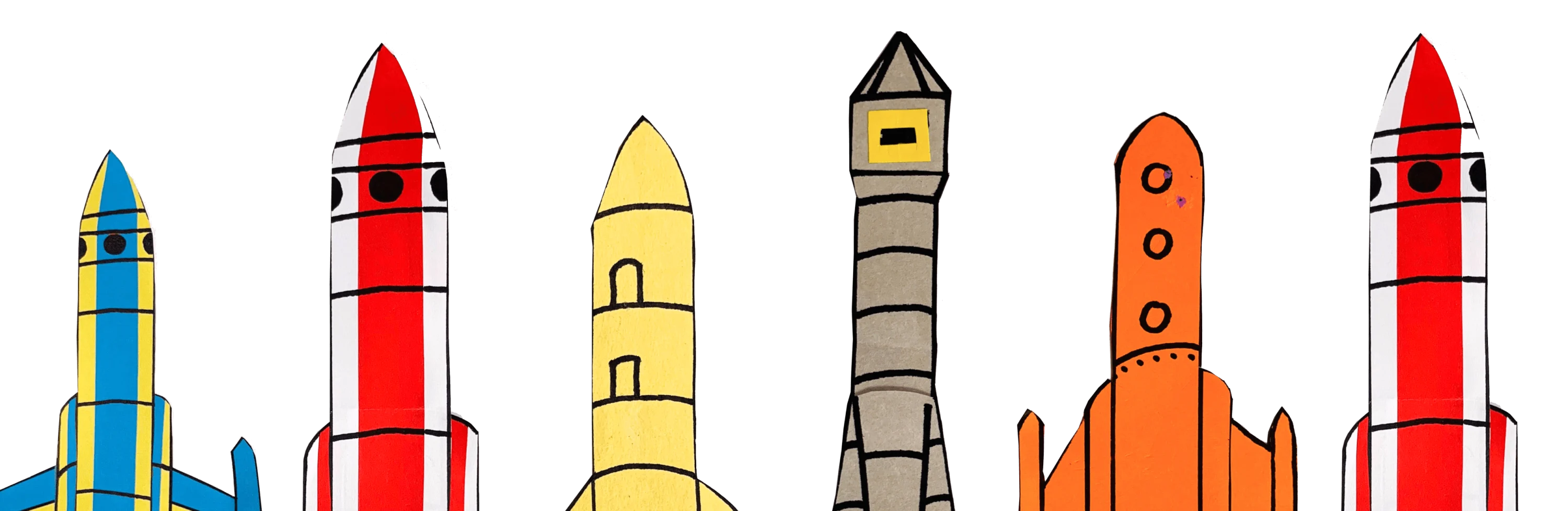

The IDLES track Olivier and Michel are working on is called Model Village, taken from the band’s forthcoming, highly-anticipated album Ultra-Mono. “First of all, we exchange our feelings about the song and if we like it or not,” explains Michel, about he and Olivier’s process. “Then we respond or discuss how we would like to do it. Olivier said to me: ‘I’d like to find a video that uses a lot of this kind of effects,’ whereas me, I am into this cutout paper approach, so he said, ‘Let's join those two techniques.’” They then discussed their approach with Joe: an animation based around a small town, with a pub, a cemetery, a rocket (casual), that sort of thing, hand-drawn and cut by Michel and animated by Olivier using CGI.

The song is really about the dangerous small-mindedness born out of villages which can sometimes act as breeding grounds for far right politics. The lyrics paint a very strong visual picture of the kinds of characters you’d find in this kind of village. Michel latched on to one line: “There's a lot of pink skin in the village” and decided to run with it, making all the villagers into pigs. “Basically in the first part,” Michel explains, “we try to illustrate the lyrics as close as possible, to create the world, and then in the second half...they go to the moon.” The collages made by Michel on a flat surface were then transformed by Olivier into a moving, 3D village using an effect which makes us feel like we’re hovering over the town in a helicopter. Michel says this effect feels like looking through a snorkelling mask underwater: some parts of your vision blurred, and some in a heightened state of clarity. Olivier finds it funny that Michel sees this complicated CGI technique as “underwater” – he understands what he means, and also that few others would have made that comparison. “That’s his way to express it,” he says, smiling.

At a glance, Michel’s drawings and the cut-out look of the town is the sort of thing an artistic child might have dreamt up for a project in elementary school – if it had a relatively big budget and was animated by one of the best post production creatives working today. The fact that Michel took Joe’s song about something dark and problematic and turned it into a cartoon about pigs is what makes Michel so extraordinary. In an interview on a website called The Talks, Michel says: "When you become an adult you often have to limit your creativity – I mean, you can still be creative if you are working in a system – but if you do creativity that is only connected to pleasure, then you make big electric trains and you seem to be either a child molester or a big kid. I am a little bit of a big kid...If being an adult is becoming cynical or pretentious then I prefer to stay immature."

I asked Joe if Michel’s ability to be vulnerable and child-like was something that moved him, or influenced how he saw his own creativity. “Something that I learned from Gondry is a vulnerability with playfulness: allowing your imagination, innocence and naivety to come through as your strength is a massive thing,” Joe says. “Gondry's visual language is sometimes crude, but always playful. There's no lie there. It's a very vulnerable and visceral art form that he's created where you see him actually animating his imagination.” This is more than just a creative trick, or ability. To Joe it means something much deeper than that. “ is handmade and it's human and that's something that our society pushes against: you need to be perfect, you need to look perfect and everything needs to be seamless and strong. But actually vulnerability and naivety is a strength. To be vulnerable and to be naive is to have empathy. And so, to empathize with your adversaries and allow yourself to be naked on film or on record is a really strong thing to do. It liberates you and it also liberates your audience. And that's something that I hope that can do, that Gondry's been doing for fucking years.”

If this project – a collaborative effort made by three creatives in different locations all over the world, in lockdown – were a music video, how would it look?

Would we fly around the world and zoom into a band practice in a warehouse and watch IDLES reigniting their collective sound and energy after months of lockdown, preparing to tour once again. Or maybe we’d be with Joe, windscreen wipers going like crazy, driving up and down the M4. Then we could fly over the Channel to see Olivier greeting his son in his Parisian apartment and FaceTiming Michel about edits from his little computer room. Perhaps we’d then teleport over the Atlantic and across America to Michel’s studio in LA, where he sits, smiling, in his yellow T-shirt, happily cutting out hundreds and hundreds of paper shapes for Olivier to put against the music, and bring to life.